The gap between quality-as-imagined and quality-as-done doesn’t emerge from inadequate procedures or insufficient training budgets. It emerges from a fundamental failure to transfer the reasoning, judgment, and adaptive capacity that expert quality professionals deploy every day but rarely articulate explicitly. This knowledge—how to navigate the tension between regulatory compliance and operational reality, how to distinguish signal from noise in deviation trends, how to conduct investigations that identify causal mechanisms rather than document procedural failures—doesn’t transmit effectively through classroom training or SOP review. It requires mentorship.

Yet pharmaceutical quality organizations treat mentorship as a peripheral benefit rather than critical infrastructure. When we discuss quality culture, we focus on leadership commitment, clear procedures, adequate resources, and accountability systems. These matter. But without deliberate mentorship structures that transfer tacit quality expertise from experienced professionals to developing ones, we’re building quality systems on the assumption that technical competence alone generates quality judgment. That assumption fails predictably and expensively.

A recent Harvard Business Review article on organizational mentorship culture provides a framework that translates powerfully to pharmaceutical quality contexts. The authors distinguish between running mentoring programs—tactical initiatives with clear participants and timelines—and fostering mentoring cultures where mentorship permeates the organization as an expected practice rather than a special benefit. That distinction matters enormously for quality functions.

Quality organizations running mentoring programs might pair high-potential analysts with senior managers for quarterly conversations about career development. Quality organizations with mentoring cultures embed expectation and practice of knowledge transfer into daily operations—senior investigators routinely involve junior colleagues in root cause analysis, experienced auditors deliberately explain their risk-based thinking during facility walkthroughs, quality managers create space for emerging leaders to struggle productively with complex regulatory interpretations before providing their own conclusions.

The difference isn’t semantic. It’s the difference between quality systems that can adapt and improve versus systems that stagnate despite impressive procedure libraries and training completion metrics.

The Organizational Blind Spot: High Performers Left to Navigate Development Alone

The HBR article describes a scenario that resonates uncomfortably with pharmaceutical quality career paths: Maria, a high-performing marketing professional, was overlooked for promotion because strong technical results didn’t automatically translate to readiness for increased responsibility. She assumed performance alone would drive progression. Her manager recognized a gap between Maria’s current behaviors and those required for senior roles but also recognized she wasn’t the right person to develop those capabilities—her focus was Maria’s technical performance, not her strategic development.

This pattern repeats constantly in pharmaceutical quality organizations. A QC analyst demonstrates excellent technical capability—meticulous documentation, strong analytical troubleshooting, consistent detection of out-of-specification results. Based on this performance, they’re promoted to Senior Analyst or given investigation leadership responsibilities. Suddenly they’re expected to demonstrate capabilities that excellent technical work neither requires nor develops: distinguishing between adequate and excellent investigation depth, navigating political complexity when investigations implicate manufacturing process decisions, mentoring junior analysts while managing their own workload.

Nobody mentions mentoring because everything seemed to be going well. The analyst was meeting expectations. Training records were current. Performance reviews were positive. But the knowledge required for the next level—how to think like a senior quality professional rather than execute like a proficient technician—was never deliberately transferred.

I’ve seen this failure mode throughout my career leading quality organizations. We promote based on technical excellence, then express frustration when newly promoted professionals struggle with judgment, strategic thinking, or leadership capabilities. We attribute these struggles to individual limitations rather than systematic organizational failure to develop those capabilities before they became job requirements.

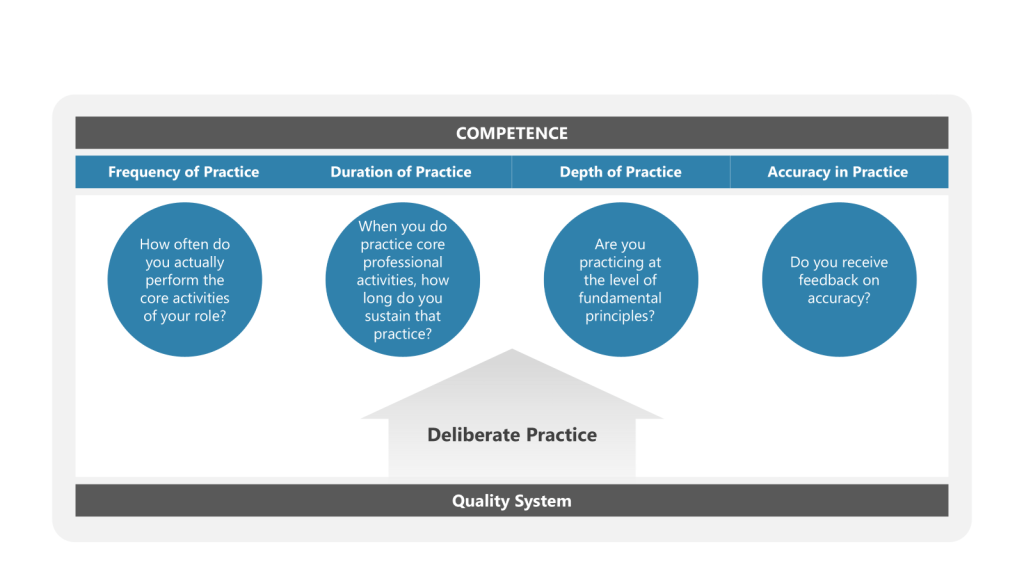

The assumption underlying this failure is that professional development naturally emerges from experience plus training. Put capable people in challenging roles, provide required training, and development follows. This assumption ignores what research on expertise consistently demonstrates: expert performance emerges from deliberate practice with feedback, not accumulated experience. Without structured mentorship providing that feedback and guiding that deliberate practice, experience often just reinforces existing patterns rather than developing new capabilities.

Why Generic Mentorship Programs Fail in Quality Contexts

Pharmaceutical companies increasingly recognize mentorship value and implement formal mentoring programs. According to the HBR article, 98% of Fortune 500 companies offered visible mentoring programs in 2024. Yet uptake remains remarkably low—only 24% of employees use available programs. Employees cite time pressures, unclear expectations, limited training, and poor program visibility as barriers.

These barriers intensify in quality functions. Quality professionals already face impossible time allocation challenges—investigation backlogs, audit preparation, regulatory submission support, training delivery, change control review, deviation trending. Adding mentorship meetings to calendars already stretched beyond capacity feels like another corporate initiative disconnected from operational reality.

But the deeper problem with generic mentoring programs in quality contexts is misalignment between program structure and quality knowledge characteristics. Most corporate mentoring programs focus on career development, leadership skills, networking, and organizational navigation. These matter. But they don’t address the specific knowledge transfer challenges unique to pharmaceutical quality practice.

Quality expertise is deeply contextual and often tacit. An experienced investigator approaching a potential product contamination doesn’t follow a decision tree. They’re integrating environmental monitoring trends, recent facility modifications, similar historical events, understanding of manufacturing process vulnerabilities, assessment of analytical method limitations, and pattern recognition across hundreds of previous investigations. Much of this reasoning happens below conscious awareness—it’s System 1 thinking in Kahneman’s framework, rapid and automatic.

When mentoring focuses primarily on career development conversations, it misses the opportunity to make this tacit expertise explicit. The most valuable mentorship for a junior quality professional isn’t quarterly career planning discussions. It’s the experienced investigator talking through their reasoning during an active investigation: “I’m focusing on the environmental monitoring because the failure pattern suggests localized contamination rather than systemic breakdown, and these three recent EM excursions in the same suite caught my attention even though they were all within action levels…” That’s knowledge transfer that changes how the mentee will approach their next investigation.

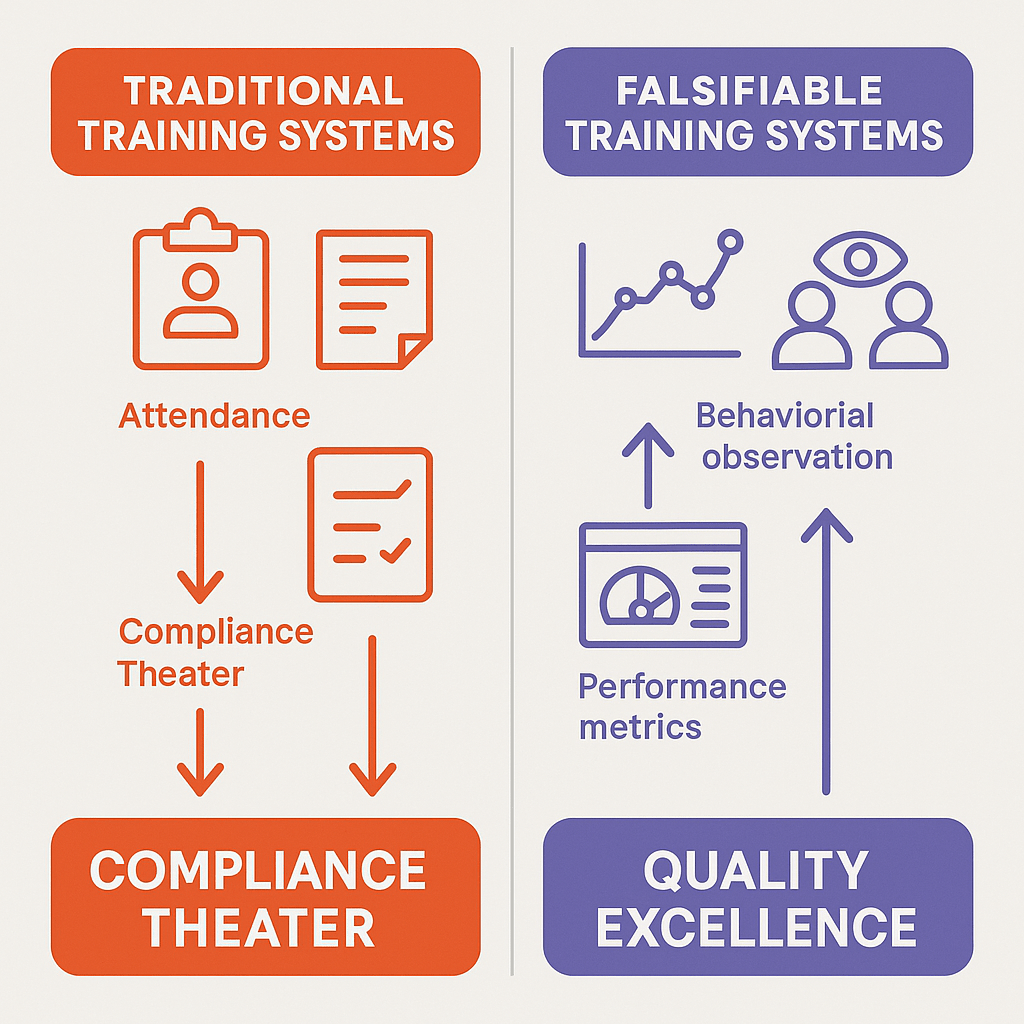

Generic mentoring programs also struggle with the falsifiability challenge I’ve been exploring on this blog. When mentoring success metrics focus on program participation rates, satisfaction surveys, and retention statistics, they measure mentoring-as-imagined (career discussions happened, participants felt supported) rather than mentoring-as-done (quality judgment improved, investigation quality increased, regulatory inspection findings decreased). These programs can look successful while failing to transfer the quality expertise that actually matters for organizational performance.

Evidence for Mentorship Impact: Beyond Engagement to Quality Outcomes

Despite implementation challenges, research evidence for mentorship impact is substantial. The HBR article cites multiple studies demonstrating that mentees were promoted at more than twice the rate of non-participants, mentoring delivered ROI of 1000% or better, and 70% of HR leaders reported mentoring enhanced business performance. A 2021 meta-analysis in the Journal of Vocational Behavior found strong correlations between mentoring, job performance, and career satisfaction across industries.

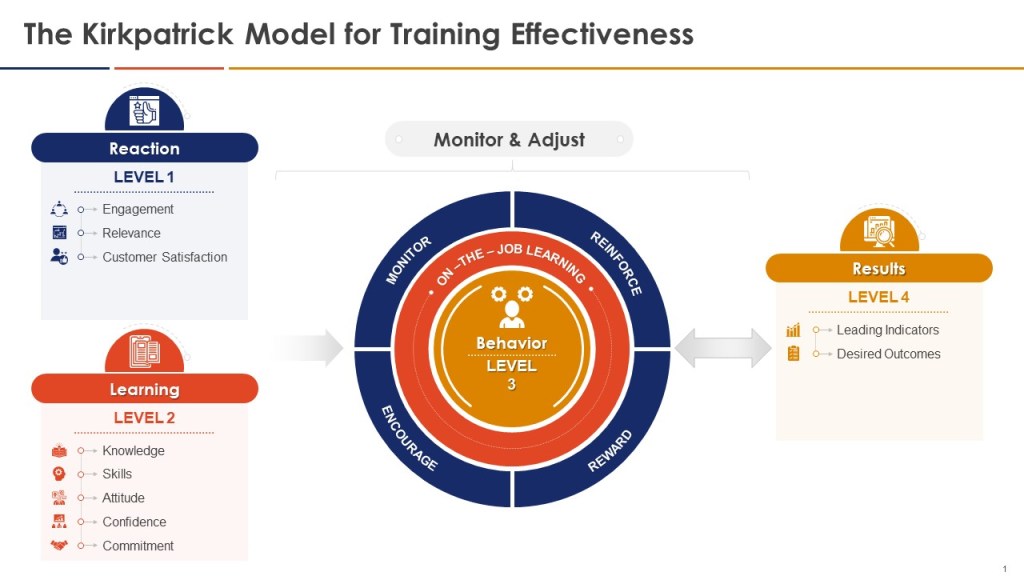

These findings align with broader research on expertise development. Anders Ericsson’s work on deliberate practice demonstrates that expert performance requires not just experience but structured practice with immediate feedback from more expert practitioners. Mentorship provides exactly this structure—experienced quality professionals providing feedback that helps developing professionals identify gaps between their current performance and expert performance, then deliberately practicing specific capabilities to close those gaps.

In pharmaceutical quality contexts, mentorship impact manifests in several measurable dimensions that directly connect to organizational quality outcomes:

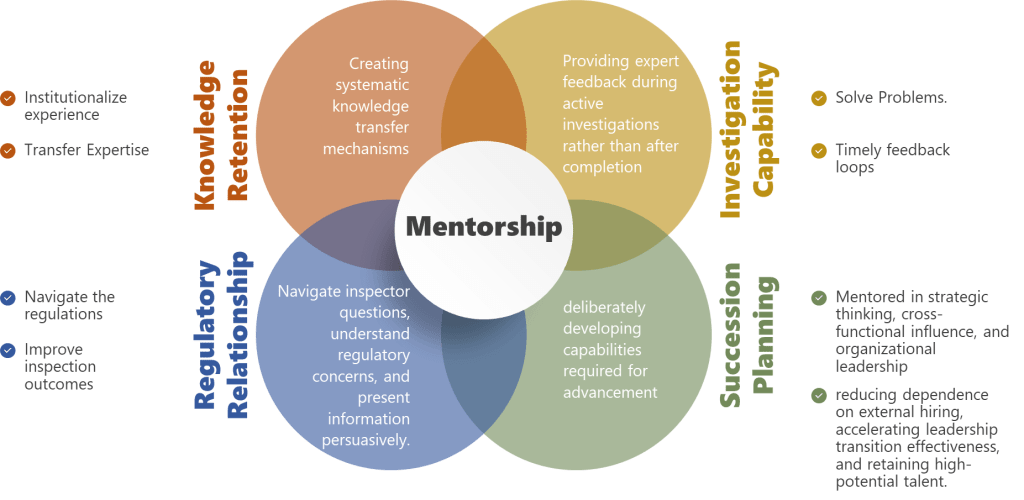

Investigation quality and cycle time—Organizations with strong mentorship cultures produce investigations that more reliably identify causal mechanisms rather than documenting procedural failures. Junior investigators mentored through multiple complex investigations develop pattern recognition and causal reasoning capabilities that would take years to develop through independent practice. This translates to shorter investigation cycles (less rework when initial investigation proves inadequate) and more effective CAPAs (addressing actual causes rather than superficial procedural gaps).

Regulatory inspection resilience—Quality professionals who’ve been mentored through inspection preparation and response demonstrate better real-time judgment during inspections. They’ve observed how experienced professionals navigate inspector questions, balance transparency with appropriate context, and distinguish between minor observations requiring acknowledgment versus potential citations requiring immediate escalation. This tacit knowledge doesn’t transfer through training on FDA inspection procedures—it requires observing and debriefing actual inspection experiences with expert mentors.

Adaptive capacity during operational challenges—Mentorship develops the capability to distinguish when procedures should be followed rigorously versus when procedures need adaptive interpretation based on specific circumstances. This is exactly the work-as-done versus work-as-imagined tension that Sidney Dekker emphasizes. Junior quality professionals without mentorship default to rigid procedural compliance (safest from personal accountability perspective) or make inappropriate exceptions (lacking judgment to distinguish justified from unjustified deviation). Experienced mentors help develop the judgment required to navigate this tension appropriately.

Knowledge retention during turnover—Perhaps most critically for pharmaceutical manufacturing, mentorship creates explicit transfer of institutional knowledge that otherwise walks out the door when experienced professionals leave. The experienced QA manager who remembers why specific change control categories exist, which regulatory commitments drove specific procedural requirements, and which historical issues inform current risk assessments—without deliberate mentorship, that knowledge disappears at retirement, leaving the organization vulnerable to repeating historical failures.

The ROI calculation for quality mentorship should account for these specific outcomes. What’s the cost of investigation rework cycles? What’s the cost of FDA Form 483 observations requiring CAPA responses? What’s the cost of lost production while investigating contamination events that experienced professionals would have prevented through better environmental monitoring interpretation? What’s the cost of losing manufacturing licenses because institutional knowledge critical for regulatory compliance wasn’t transferred before key personnel retired?

When framed against these costs, the investment in structured mentorship—time allocation for senior professionals to mentor, reduced direct productivity while developing professionals learn through observation and guided practice, programmatic infrastructure to match mentors with mentees—becomes obviously justified. The problem is that mentorship costs appear on operational budgets as reduced efficiency, while mentorship benefits appear as avoided costs that are invisible until failures occur.

From Mentoring Programs to Mentoring Culture: The Infrastructure Challenge

The HBR framework distinguishes programs from culture by emphasizing permeation and normalization. Mentoring programs are tactical—specific participants, clear timelines, defined objectives. Mentoring cultures embed mentorship expectations throughout the organization such that receiving and providing mentorship becomes normal professional practice rather than a special developmental opportunity.

This distinction maps directly onto quality culture challenges. Organizations with quality programs have quality departments, quality procedures, quality training, quality metrics. Organizations with quality cultures have quality thinking embedded throughout operational decision-making—manufacturing doesn’t view quality as external oversight but as integrated partnership, investigations focus on understanding what happened rather than documenting compliance, regulatory commitments inform operational planning rather than appearing as constraints after plans are established.

Building quality culture requires exactly the same permeation and normalization that building mentoring culture requires. And these aren’t separate challenges—they’re deeply interconnected. Quality culture emerges when quality judgment becomes distributed throughout the organization rather than concentrated in the quality function. That distribution requires knowledge transfer. Knowledge transfer of complex professional judgment requires mentorship.

The pathway from mentoring programs to mentoring culture in quality organizations involves several specific shifts:

From Opt-In to Default Expectation

The HBR article recommends shifting from opt-in to opt-out mentoring so support becomes a default rather than a benefit requiring active enrollment. In quality contexts, this means embedding mentorship into role expectations rather than treating it as additional responsibility.

When I’ve implemented this approach, it looks like clear articulation in job descriptions and performance objectives: “Senior Investigators are expected to mentor at least two developing investigators through complex investigations annually, with documented knowledge transfer and mentee capability development.” Not optional. Not extra credit. Core job responsibility with the same performance accountability as investigation completion and regulatory response.

Similarly for mentees: “QA Associates are expected to engage actively with assigned mentors, seeking guidance on complex quality decisions and debriefing experiences to accelerate capability development.” This frames mentorship as professional responsibility rather than optional benefit.

The challenge is time allocation. If mentorship is a core expectation, workload planning must account for it. A senior investigator expected to mentor two people through complex investigations cannot also carry the same investigation load as someone without mentorship responsibilities. Organizations that add mentorship expectations without adjusting other performance expectations are creating mentorship theater—the appearance of commitment without genuine resource allocation.

This requires honest confrontation with capacity constraints. If investigation workload already exceeds capacity, adding mentorship expectations just creates another failure mode where people are accountable for obligations they cannot possibly fulfill. The alternative is reducing other expectations to create genuine space for mentorship—which forces difficult prioritization conversations about whether knowledge transfer and capability development matter more than marginal investigation throughput increases.

Embedding Mentorship into Performance and Development Processes

The HBR framework emphasizes integrating mentorship into performance conversations rather than treating it as standalone initiative. Line managers should be trained to identify development needs served through mentoring and explore progress during check-ins and appraisals.

In quality organizations, this integration happens at multiple levels. Individual development plans should explicitly identify capabilities requiring mentorship rather than classroom training. Investigation management processes should include mentorship components—complex investigations assigned to mentor-mentee pairs rather than individual investigators, with explicit expectation that mentors will transfer reasoning processes not just task completion.

Quality system audits and management reviews should assess mentorship effectiveness as quality system element. Are investigations led by recently mentored professionals showing improved causal reasoning? Are newly promoted quality managers demonstrating judgment capabilities suggesting effective mentorship? Are critical knowledge areas identified for transfer before experienced professionals leave?

The falsifiable systems approach I’ve advocated demands testable predictions. A mentoring culture makes specific predictions about performance: professionals who receive structured mentorship in investigation techniques will produce higher quality investigations than those who develop through independent practice alone. This prediction can be tested—and potentially falsified—through comparison of investigation quality metrics between mentored and non-mentored populations.

Organizations serious about quality culture should conduct exactly this analysis. If mentorship isn’t producing measurable improvement in quality performance, either the mentorship approach needs revision or the assumption that mentorship improves quality performance is wrong. Most organizations avoid this test because they’re not confident in the answer—which suggests they’re engaged in mentorship theater rather than genuine capability development.

Cross-Functional Mentorship: Breaking Quality Silos

The HBR article emphasizes that senior leaders should mentor beyond their direct teams to ensure objectivity and transparency. Mentors outside the mentee’s reporting line can provide perspective and feedback that direct managers cannot.

This principle is especially powerful in quality contexts when applied cross-functionally. Quality professionals mentored exclusively within quality functions risk developing insular perspectives that reinforce quality-as-imagined disconnected from manufacturing-as-done. Manufacturing professionals mentored exclusively within manufacturing risk developing operational perspectives disconnected from regulatory requirements and patient safety considerations.

Cross-functional mentorship addresses these risks while building organizational capabilities that strengthen quality culture. Consider several specific applications:

Manufacturing leaders mentoring quality professionals—An experienced manufacturing director mentoring a QA manager helps the QA manager understand operational constraints, equipment limitations, and process variability from manufacturing perspective. This doesn’t compromise quality oversight—it makes oversight more effective by grounding regulatory interpretation in operational reality. The QA manager learns to distinguish between regulatory requirements demanding rigid compliance versus areas where risk-based interpretation aligned with manufacturing capabilities produces better patient outcomes than theoretical ideals disconnected from operational possibility.

Quality leaders mentoring manufacturing professionals—Conversely, an experienced quality director mentoring a manufacturing supervisor helps the supervisor understand how manufacturing decisions create quality implications and regulatory commitments. The supervisor learns to anticipate how process changes will trigger change control requirements, how equipment qualification status affects operational decisions, and how data integrity practices during routine manufacturing become critical evidence during investigations. This knowledge prevents problems rather than just catching them after occurrence.

Reverse mentoring on emerging technologies and approaches—The HBR framework mentions reverse and peer mentoring as equally important to traditional hierarchical mentoring. In quality contexts, reverse mentoring becomes especially valuable around emerging technologies, data analytics approaches, and new regulatory frameworks. A junior quality analyst with strong statistical and data visualization capabilities mentoring a senior quality director on advanced trending techniques creates mutual benefit—the director learns new analytical approaches while the analyst gains understanding of how to make analytical insights actionable in regulatory contexts.

Cross-site mentoring for platform knowledge transfer—For organizations with multiple manufacturing sites, cross-site mentoring creates powerful platform knowledge transfer mechanisms. An experienced quality manager from a mature site mentoring quality professionals at a newer site transfers not just procedural knowledge but judgment about what actually matters versus what looks impressive in procedures but doesn’t drive quality outcomes. This prevents newer sites from learning through expensive failures that mature sites have already experienced.

The organizational design challenge is creating infrastructure that enables and incentivizes cross-functional mentorship despite natural siloing tendencies. Mentorship expectations in performance objectives should explicitly include cross-functional components. Recognition programs should highlight cross-functional mentoring impact. Senior leadership communications should emphasize cross-functional mentoring as strategic capability development rather than distraction from functional responsibilities.

Measuring Mentorship: Individual Development and Organizational Capability

The HBR framework recommends measuring outcomes both individually and organizationally, encouraging mentors and mentees to set clear objectives while also connecting individual progress to organizational objectives. This dual measurement approach addresses the falsifiability challenge—ensuring mentorship programs can be tested against claims about impact rather than just demonstrated as existing.

Individual measurement focuses on capability development aligned with career progression and role requirements. For quality professionals, this might include:

Investigation capabilities—Mentees should demonstrate progressive improvement in investigation quality based on defined criteria: clarity of problem statements, thoroughness of data gathering, rigor of causal analysis, effectiveness of CAPA identification. Mentors and mentees should review investigation documentation together, comparing mentee reasoning processes to expert reasoning and identifying specific capability gaps requiring deliberate practice.

Regulatory interpretation judgment—Quality professionals must constantly interpret regulatory requirements in specific operational contexts. Mentorship should develop this judgment through guided practice—mentor and mentee reviewing the same regulatory scenario, mentee articulating their interpretation and rationale, mentor providing feedback on reasoning quality and identifying considerations the mentee missed. Over time, mentee interpretations should converge toward expert quality with less guidance required.

Risk assessment and prioritization—Developing quality professionals often struggle with risk-based thinking, defaulting to treating everything as equally critical. Mentorship should deliberately develop risk intuition through discussion of specific scenarios: “Here are five potential quality issues—how would you prioritize investigation resources?” Mentor feedback explains expert risk reasoning, helping mentee calibrate their own risk assessment against expert judgment.

Technical communication and influence—Quality professionals must communicate complex technical and regulatory concepts to diverse audiences—regulatory agencies, senior management, manufacturing personnel, external auditors. Mentorship develops this capability through observation (mentees attending regulatory meetings led by mentors), practice with feedback (mentees presenting draft communications for mentor review before external distribution), and guided reflection (debriefing presentations and identifying communication approaches that succeeded or failed).

These individual capabilities should be assessed through demonstrated performance, not self-report satisfaction surveys. The question isn’t whether mentees feel supported or believe they’re developing—it’s whether their actual performance demonstrates capability improvement measurable through work products and outcomes.

Organizational measurement focuses on whether mentorship programs translate to quality system performance improvements:

Investigation quality trending—Organizations should track investigation quality metrics across mentored versus non-mentored populations and over time for individuals receiving mentorship. Quality metrics might include: percentage of investigations identifying credible root causes versus concluding with “human error”, investigation cycle time, CAPA effectiveness (recurrence rates for similar events), regulatory inspection findings related to investigation quality. If mentorship improves investigation capability, these metrics should show measurable differences.

Regulatory inspection outcomes—Organizations with strong quality mentorship should demonstrate better regulatory inspection outcomes—fewer observations, faster response cycles, more credible CAPA plans. While multiple factors influence inspection outcomes, tracking inspection performance alongside mentorship program maturity provides indication of organizational impact. Particularly valuable is comparing inspection findings between facilities or functions with strong mentorship cultures versus those with weaker mentorship infrastructure within the same organization.

Knowledge retention and transfer—Organizations should measure whether critical quality knowledge transfers successfully during personnel transitions. When experienced quality professionals leave, do their successors demonstrate comparable judgment and capability, or do quality metrics deteriorate until new professionals develop through independent experience? Strong mentorship programs should show smoother transitions with maintained or improved performance rather than capability gaps requiring years to rebuild.

Succession pipeline health—Quality organizations need robust internal pipelines preparing professionals for increasing responsibility. Mentorship programs should demonstrate measurable pipeline development—percentage of senior quality roles filled through internal promotion, time required for promoted professionals to demonstrate full capability in new roles, retention of high-potential quality professionals. Organizations with weak mentorship typically show heavy external hiring for senior roles (internal candidates lack required capabilities), extended learning curves when internal promotions occur, and turnover of high-potential professionals who don’t see clear development pathways.

The measurement framework should be designed for falsifiability—creating testable predictions that could prove mentorship programs ineffective. If an organization invests significantly in quality mentorship programs but sees no measurable improvement in investigation quality, regulatory outcomes, knowledge retention, or succession pipeline health, that’s important information demanding program revision or recognition that mentorship isn’t generating claimed benefits.

Most organizations avoid this level of measurement rigor because they’re not confident in results. Mentorship programs become articles of faith—assumed to be beneficial without empirical testing. This is exactly the kind of unfalsifiable quality system I’ve critiqued throughout this blog. Genuine commitment to quality culture requires honest measurement of whether quality initiatives actually improve quality outcomes.

Work-As-Done in Mentorship: The Implementation Gap

Mentorship-as-imagined involves structured meetings where experienced mentors transfer knowledge to developing mentees through thoughtful discussions aligned with individual development plans. Mentors are skilled at articulating tacit knowledge, mentees are engaged and actively seeking growth, organizations provide adequate time and support, and measurable capability development results.

Mentorship-as-done often looks quite different. Mentors are senior professionals already overwhelmed with operational responsibilities, struggling to find time for scheduled mentorship meetings and unprepared to structure developmental conversations effectively when meetings do occur. They have deep expertise but limited conscious access to their own reasoning processes and even less experience articulating those processes pedagogically. Mentees are equally overwhelmed, viewing mentorship meetings as another calendar obligation rather than developmental opportunity, and uncertain what questions to ask or how to extract valuable knowledge from limited meeting time.

Organizations schedule mentorship programs, create matching processes, provide brief mentor training, then declare victory when participation metrics look acceptable—while actual knowledge transfer remains minimal and capability development indistinguishable from what would have occurred through independent experience.

I’ve observed this implementation gap repeatedly when introducing formal mentorship into quality organizations. The gap emerges from several systematic failures:

Insufficient time allocation—Organizations add mentorship expectations without reducing other responsibilities. A senior investigator told to mentor two junior colleagues while maintaining their previous investigation load simply cannot fulfill both expectations adequately. Mentorship becomes the discretionary activity sacrificed when workload pressures mount—which is always. Genuine mentorship requires genuine time allocation, meaning reduced expectations for other deliverables or additional staffing to maintain throughput.

Lack of mentor development—Being expert quality practitioners doesn’t automatically make professionals effective mentors. Mentoring requires different capabilities: articulating tacit reasoning processes, identifying mentee knowledge gaps, structuring developmental experiences, providing constructive feedback, maintaining mentoring relationships through operational pressures. Organizations assume these capabilities exist or develop naturally rather than deliberately developing them through mentor training and mentoring-the-mentors programs.

Mismatch between mentorship structure and knowledge characteristics—Many mentorship programs structure around scheduled meetings for career discussions. This works for developing professional skills like networking, organizational navigation, and career planning. It doesn’t work well for developing technical judgment that emerges in context. The most valuable mentorship for investigation capability doesn’t happen in scheduled meetings—it happens during actual investigations when mentor and mentee are jointly analyzing data, debating hypotheses, identifying evidence gaps, and reasoning about causation. Organizations need mentorship structures that embed mentoring into operational work rather than treating it as separate activity.

Inadequate mentor-mentee matching—Generic matching based on availability and organizational hierarchy often creates mismatched pairs where mentor expertise doesn’t align with mentee development needs or where interpersonal dynamics prevent effective knowledge transfer. The HBR article emphasizes that good mentors require objectivity and the ability to make mentees comfortable sharing transparently—qualities undermined when mentors are in direct reporting lines or have conflicts of interest. Quality organizations need thoughtful matching considering expertise alignment, developmental needs, interpersonal compatibility, and organizational positioning.

Absence of accountability and measurement—Without clear accountability for mentorship outcomes and measurement of mentorship effectiveness, programs devolve into activity theater. Mentors and mentees go through motions of scheduled meetings while actual capability development remains minimal. Organizations need specific, measurable expectations for both mentors and mentees, regular assessment of whether those expectations are being met, and consequences when they’re not—just as with any other critical organizational responsibility.

Addressing these implementation gaps requires moving beyond mentorship programs to genuine mentorship culture. Culture means expectations, norms, accountability, and resource allocation aligned with stated priorities. Organizations claiming quality mentorship is a priority while providing no time allocation, no mentor development, no measurement, and no accountability for outcomes aren’t building mentorship culture—they’re building mentorship theater.

Practical Implementation: Building Quality Mentorship Infrastructure

Building authentic quality mentorship culture requires deliberate infrastructure addressing the implementation gaps between mentorship-as-imagined and mentorship-as-done. Based on both the HBR framework and my experience implementing quality mentorship in pharmaceutical manufacturing, several practical elements prove critical:

1. Embed Mentorship in Onboarding and Role Transitions

New hire onboarding provides natural mentorship opportunity that most organizations underutilize. Instead of generic orientation training followed by independent learning, structured onboarding should pair new quality professionals with experienced mentors for their first 6-12 months. The mentor guides the new hire through their first investigations, change control reviews, audit preparations, and regulatory interactions—not just explaining procedures but articulating the reasoning and judgment underlying quality decisions.

This onboarding mentorship should include explicit knowledge transfer milestones: understanding of regulatory framework and organizational commitments, capability to conduct routine quality activities independently, judgment to identify when escalation or consultation is appropriate, integration into quality team and cross-functional relationships. Successful onboarding means the new hire has internalized not just what to do but why, developing foundation for continued capability growth rather than just procedural compliance.

Role transitions create similar mentorship opportunities. When quality professionals are promoted or move to new responsibilities, assigning experienced mentors in those roles accelerates capability development and reduces failure risk. A newly promoted QA manager benefits enormously from mentorship by an experienced QA director who can guide them through their first regulatory inspection, first serious investigation, first contentious cross-functional negotiation—helping them develop judgment through guided practice rather than expensive independent trial-and-error.

2. Create Operational Mentorship Structures

The most valuable quality mentorship happens during operational work rather than separate from it. Organizations should structure operational processes to enable embedded mentorship:

Investigation mentor-mentee pairing—Complex investigations should be staffed as mentor-mentee pairs rather than individual assignments. The mentee leads the investigation with mentor guidance, developing investigation capabilities through active practice with immediate expert feedback. This provides better developmental experience than either independent investigation (no expert feedback) or observation alone (no active practice).

Audit mentorship—Quality audits provide excellent mentorship opportunities. Experienced auditors should deliberately involve developing auditors in audit planning, conduct, and reporting—explaining risk-based audit strategy, demonstrating interview techniques, articulating how they distinguish significant findings from minor observations, and guiding report writing that balances accuracy with appropriate tone.

Regulatory submission mentorship—Regulatory submissions require judgment about what level of detail satisfies regulatory expectations, how to present data persuasively, and how to address potential deficiencies proactively. Experienced regulatory affairs professionals should mentor developing professionals through their first submissions, providing feedback on draft content and explaining reasoning behind revision recommendations.

Cross-functional meeting mentorship—Quality professionals must regularly engage with cross-functional partners in change control meetings, investigation reviews, management reviews, and strategic planning. Experienced quality leaders should bring developing professionals to these meetings as observers initially, then active participants with debriefing afterward. The debrief addresses what happened, why particular approaches succeeded or failed, what the mentee noticed or missed, and how expert quality professionals navigate cross-functional dynamics effectively.

These operational mentorship structures require deliberate process design. Investigation procedures should explicitly describe mentor-mentee investigation approaches. Audit planning should consider developmental opportunities alongside audit objectives. Meeting attendance should account for mentorship value even when the developing professional’s direct contribution is limited.

3. Develop Mentors Systematically

Effective mentoring requires capabilities beyond subject matter expertise. Organizations should develop mentors through structured programs addressing:

Articulating tacit knowledge—Expert quality professionals often operate on intuition developed through extensive experience—they “just know” when an investigation needs deeper analysis or a regulatory interpretation seems risky. Mentor development should help experts make this tacit knowledge explicit by practicing articulation of their reasoning processes, identifying the cues and patterns driving their intuitions, and developing vocabulary for concepts they previously couldn’t name.

Providing developmental feedback—Mentors need capability to provide feedback that improves mentee performance without being discouraging or creating defensiveness. This requires distinguishing between feedback on work products (investigation reports, audit findings, regulatory responses) and feedback on reasoning processes underlying those products. Product feedback alone doesn’t develop capability—mentees need to understand why their reasoning was inadequate and how expert reasoning differs.

Structuring developmental conversations—Effective mentorship conversations follow patterns: asking mentees to articulate their reasoning before providing expert perspective, identifying specific capability gaps rather than global assessments, creating action plans for deliberate practice addressing identified gaps, following up on previous developmental commitments. Mentor development should provide frameworks and practice for conducting these conversations effectively.

Managing mentorship relationships—Mentoring relationships have natural lifecycle challenges—establishing initial rapport, navigating difficult feedback conversations, maintaining connection through operational pressures, transitioning appropriately when mentees outgrow the relationship. Mentor development should address these relationship dynamics, providing guidance on building trust, managing conflict, maintaining boundaries, and recognizing when mentorship should evolve or conclude.

Organizations serious about quality mentorship should invest in systematic mentor development programs, potentially including formal mentor training, mentoring-the-mentors structures where experienced mentors guide newer mentors, and regular mentor communities of practice sharing effective approaches and addressing challenges.

4. Implement Robust Matching Processes

The quality of mentor-mentee matches substantially determines mentorship effectiveness. Poor matches—misaligned expertise, incompatible working styles, problematic organizational dynamics—generate minimal value while consuming significant time. Thoughtful matching requires considering multiple dimensions:

Expertise alignment—Mentee developmental needs should align with mentor expertise and experience. A quality professional needing to develop investigation capabilities benefits most from mentorship by an expert investigator, not a quality systems manager whose expertise centers on procedural compliance and audit management.

Organizational positioning—The HBR framework emphasizes that mentors should be outside mentees’ direct reporting lines to enable objectivity and transparency. In quality contexts, this means avoiding mentor-mentee relationships where the mentor evaluates the mentee’s performance or makes decisions affecting the mentee’s career progression. Cross-functional mentoring, cross-site mentoring, or mentoring across organizational levels (but not direct reporting relationships) provide better positioning.

Working style compatibility—Mentoring requires substantial interpersonal interaction. Mismatches in communication styles, work preferences, or interpersonal approaches create friction that undermines mentorship effectiveness. Matching processes should consider personality assessments, communication preferences, and past relationship patterns alongside technical expertise.

Developmental stage appropriateness—Mentee needs evolve as capability develops. Early-career quality professionals need mentors who excel at foundational skill development and can provide patient, detailed guidance. Mid-career professionals need mentors who can challenge their thinking and push them beyond comfortable patterns. Senior professionals approaching leadership transitions need mentors who can guide strategic thinking and organizational influence.

Mutual commitment—Effective mentoring requires genuine commitment from both mentor and mentee. Forced pairings where participants lack authentic investment generate minimal value. Matching processes should incorporate participant preferences and voluntary commitment alongside organizational needs.

Organizations can improve matching through structured processes: detailed profiles of mentor expertise and mentee developmental needs, algorithms or facilitated matching sessions pairing based on multiple criteria, trial periods allowing either party to request rematch if initial pairing proves ineffective, and regular check-ins assessing relationship health.

5. Create Accountability Through Measurement and Recognition

What gets measured and recognized signals organizational priorities. Quality mentorship cultures require measurement systems and recognition programs that make mentorship impact visible and valued:

Individual accountability—Mentors and mentees should have explicit mentorship expectations in performance objectives with assessment during performance reviews. For mentors: capability development demonstrated by mentees, quality of mentorship relationship, time invested in developmental activities. For mentees: active engagement in mentorship relationship, evidence of capability improvement, application of mentored knowledge in operational performance.

Organizational metrics—Quality leadership should track mentorship program health and impact: participation rates (while noting that universal participation is the goal, not special achievement), mentee capability development measured through work quality metrics, succession pipeline strength, knowledge retention during transitions, and ultimately quality system performance improvements associated with enhanced organizational capability.

Recognition programs—Organizations should visibly recognize effective mentoring through awards, leadership communications, and career progression. Mentoring excellence should be weighted comparably to technical excellence and operational performance in promotion decisions. When senior quality professionals are recognized primarily for investigation output or audit completion but not for developing the next generation of quality professionals, the implicit message is that knowledge transfer doesn’t matter despite explicit statements about mentorship importance.

Integration into quality metrics—Quality system performance metrics should include indicators of mentorship effectiveness: investigation quality trends for recently mentored professionals, successful internal promotions, retention of high-potential talent, knowledge transfer completeness during personnel transitions. These metrics should appear in quality management reviews alongside traditional quality metrics, demonstrating that organizational capability development is a quality system element comparable to deviation management or CAPA effectiveness.

This measurement and recognition infrastructure prevents mentorship from becoming another compliance checkbox—organizations can demonstrate through data whether mentorship programs generate genuine capability development and quality improvement or represent mentorship theater disconnected from outcomes.

The Strategic Argument: Mentorship as Quality Risk Mitigation

Quality leaders facing resource constraints and competing priorities require clear strategic rationale for investing in mentorship infrastructure. The argument shouldn’t rest on abstract benefits like “employee development” or “organizational culture”—though these matter. The compelling argument positions mentorship as critical quality risk mitigation addressing specific vulnerabilities in pharmaceutical quality systems.

Knowledge Retention Risk

Pharmaceutical quality organizations face acute knowledge retention risk as experienced professionals retire or leave. The quality director who remembers why specific procedural requirements exist, which regulatory commitments drive particular practices, and how historical failures inform current risk assessments—when that person leaves without deliberate knowledge transfer, the organization loses institutional memory critical for regulatory compliance and quality decision-making.

This knowledge loss creates specific, measurable risks: repeating historical failures because current professionals don’t understand why particular controls exist, inadvertently violating regulatory commitments because knowledge of those commitments wasn’t transferred, implementing changes that create quality issues experienced professionals would have anticipated. These aren’t hypothetical risks—I’ve investigated multiple serious quality events that occurred specifically because institutional knowledge wasn’t transferred during personnel transitions.

Mentorship directly mitigates this risk by creating systematic knowledge transfer mechanisms. When experienced professionals mentor their likely successors, critical knowledge transfers explicitly before transition rather than disappearing at departure. The cost of mentorship infrastructure should be evaluated against the cost of knowledge loss—investigation costs, regulatory response costs, potential product quality impact, and organizational capability degradation.

Investigation Capability Risk

Investigation quality directly impacts regulatory compliance, patient safety, and operational efficiency. Poor investigations fail to identify true root causes, leading to ineffective CAPAs and event recurrence. Poor investigations generate regulatory findings requiring expensive remediation. Poor investigations consume excessive time without generating valuable knowledge to prevent recurrence.

Organizations relying on independent experience to develop investigation capabilities accept years of suboptimal investigation quality while professionals learn through trial and error. During this learning period, investigations are more likely to miss critical causal factors, identify superficial rather than genuine root causes, and propose CAPAs addressing symptoms rather than causes.

Mentorship accelerates investigation capability development by providing expert feedback during active investigations rather than after completion. Instead of learning that an investigation was inadequate when it receives critical feedback during regulatory inspection or management review, mentored investigators receive that feedback during investigation conduct when it can improve the current investigation rather than just inform future attempts.

Regulatory Relationship Risk

Regulatory relationships—with FDA, EMA, and other authorities—represent critical organizational assets requiring years to build and moments to damage. These relationships depend partly on demonstrated technical competence but substantially on regulatory agencies’ confidence in organizational quality judgment and integrity.

Junior quality professionals without mentorship often struggle during regulatory interactions, providing responses that are technically accurate but strategically unwise, failing to understand inspector concerns underlying specific questions, or presenting information in ways that create rather than resolve regulatory concerns. These missteps damage regulatory relationships and can trigger expanded inspection scope or regulatory actions.

Mentorship develops regulatory interaction capabilities before professionals face high-stakes regulatory situations independently. Mentored professionals observe how experienced quality leaders navigate inspector questions, understand regulatory concerns, and present information persuasively. They receive feedback on draft regulatory responses before submission. They learn to distinguish situations requiring immediate escalation versus independent handling.

Organizations should evaluate mentorship investment against regulatory risk—potential costs of warning letters, consent decrees, import alerts, or manufacturing restrictions that can result from poor regulatory relationships exacerbated by inadequate quality professional development.

Succession Planning Risk

Quality organizations need robust internal succession pipelines to ensure continuity during planned and unplanned leadership transitions. External hiring for senior quality roles creates risks: extended learning curves while new leaders develop organizational and operational knowledge, potential cultural misalignment, and expensive recruiting and retention costs.

Yet many pharmaceutical quality organizations struggle to develop internal candidates ready for senior leadership roles. They promote based on technical excellence without developing strategic thinking, organizational influence, and leadership capabilities required for senior positions. The promoted professionals then struggle, creating performance gaps and succession planning failures.

Mentorship directly addresses succession pipeline risk by deliberately developing capabilities required for advancement before promotion rather than hoping they emerge after promotion. Quality professionals mentored in strategic thinking, cross-functional influence, and organizational leadership become viable internal succession candidates—reducing dependence on external hiring, accelerating leadership transition effectiveness, and retaining high-potential talent who see clear development pathways.

These strategic arguments position mentorship not as employee development benefit but as essential quality infrastructure comparable to laboratory equipment, quality systems software, or regulatory intelligence capabilities. Organizations invest in these capabilities because their absence creates unacceptable quality and business risk. Mentorship deserves comparable investment justification.

From Compliance Theater to Genuine Capability Development

Pharmaceutical quality culture doesn’t emerge from impressive procedure libraries, extensive training catalogs, or sophisticated quality metrics systems. These matter, but they’re insufficient. Quality culture emerges when quality judgment becomes distributed throughout the organization—when professionals at all levels understand not just what procedures require but why, not just how to detect quality failures but how to prevent them, not just how to document compliance but how to create genuine quality outcomes for patients.

That distributed judgment requires knowledge transfer that classroom training and procedure review cannot provide. It requires mentorship—deliberate, structured, measured transfer of expert quality reasoning from experienced professionals to developing ones.

Most pharmaceutical organizations claim mentorship commitment while providing no genuine infrastructure supporting effective mentorship. They announce mentoring programs without adjusting workload expectations to create time for mentoring. They match mentors and mentees based on availability rather than thoughtful consideration of expertise alignment and developmental needs. They measure participation and satisfaction rather than capability development and quality outcomes. They recognize technical achievement while ignoring knowledge transfer contribution to organizational capability.

This is mentorship theater—the appearance of commitment without genuine resource allocation or accountability. Like other forms of compliance theater that Sidney Dekker critiques, mentorship theater satisfies surface expectations while failing to deliver claimed benefits. Organizations can demonstrate mentoring program existence to leadership and regulators while actual knowledge transfer remains minimal and quality capability development indistinguishable from what would occur without any mentorship program.

Building genuine mentorship culture requires confronting this gap between mentorship-as-imagined and mentorship-as-done. It requires honest acknowledgment that effective mentorship demands time, capability, infrastructure, and accountability that most organizations haven’t provided. It requires shifting mentorship from peripheral benefit to core quality infrastructure with resource allocation and measurement commensurate to strategic importance.

The HBR framework provides actionable structure for this shift: broaden mentorship access from select high-potentials to organizational default, embed mentorship into performance management and operational processes rather than treating it as separate initiative, implement cross-functional mentorship breaking down organizational silos, measure mentorship outcomes both individually and organizationally with falsifiable metrics that could demonstrate program ineffectiveness.

For pharmaceutical quality organizations specifically, mentorship culture addresses critical vulnerabilities: knowledge retention during personnel transitions, investigation capability development affecting regulatory compliance and patient safety, regulatory relationship quality depending on quality professional judgment, and succession pipeline strength determining organizational resilience.

The organizations that build genuine mentorship cultures—with infrastructure, accountability, and measurement demonstrating authentic commitment—will develop quality capabilities that organizations relying on procedure compliance and classroom training cannot match. They’ll conduct better investigations, build stronger regulatory relationships, retain critical knowledge through transitions, and develop quality leaders internally rather than depending on expensive external hiring.

Most importantly, they’ll create quality systems characterized by genuine capability rather than compliance theater—systems that can honestly claim to protect patients because they’ve developed the distributed quality judgment required to identify and address quality risks before they become quality failures.

That’s the quality culture we need. Mentorship is how we build it.