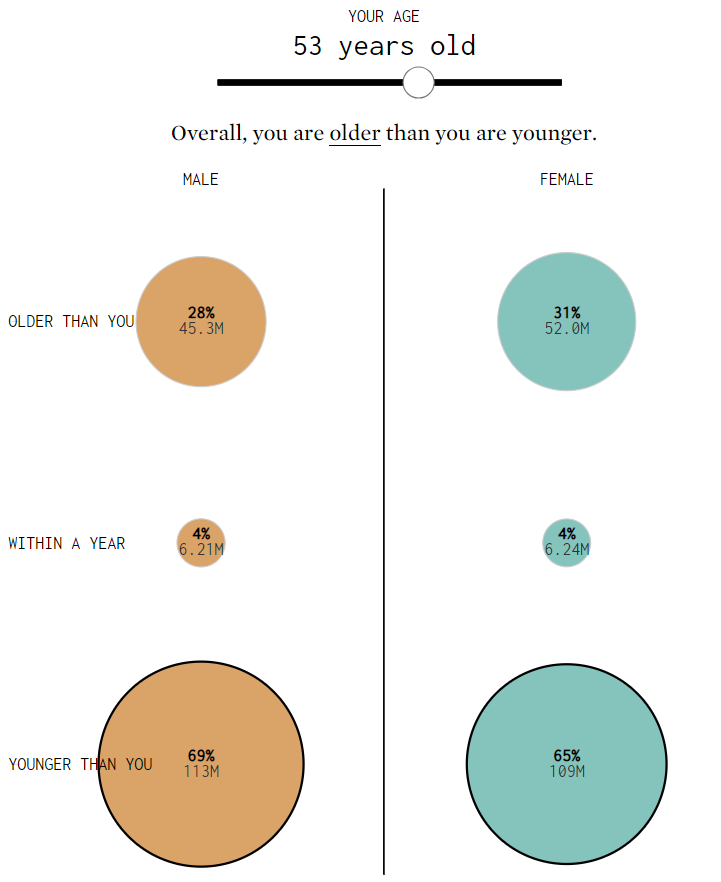

Wow, I’m older than a lot of people. When did that happen? (Shout out to my small cohort of fellow Gen-Xers!) So, in a bit of reflection, I want to discuss why I think aging in the quality profession is so critical.

The quality profession is an experience-heavy field. While formal education can provide some necessary theoretical knowledge, the practical skills required for the quality profession can only be mastered through extensive hands-on experience, practical application of skills, and the ability to adapt to real-world challenges.

Key characteristics

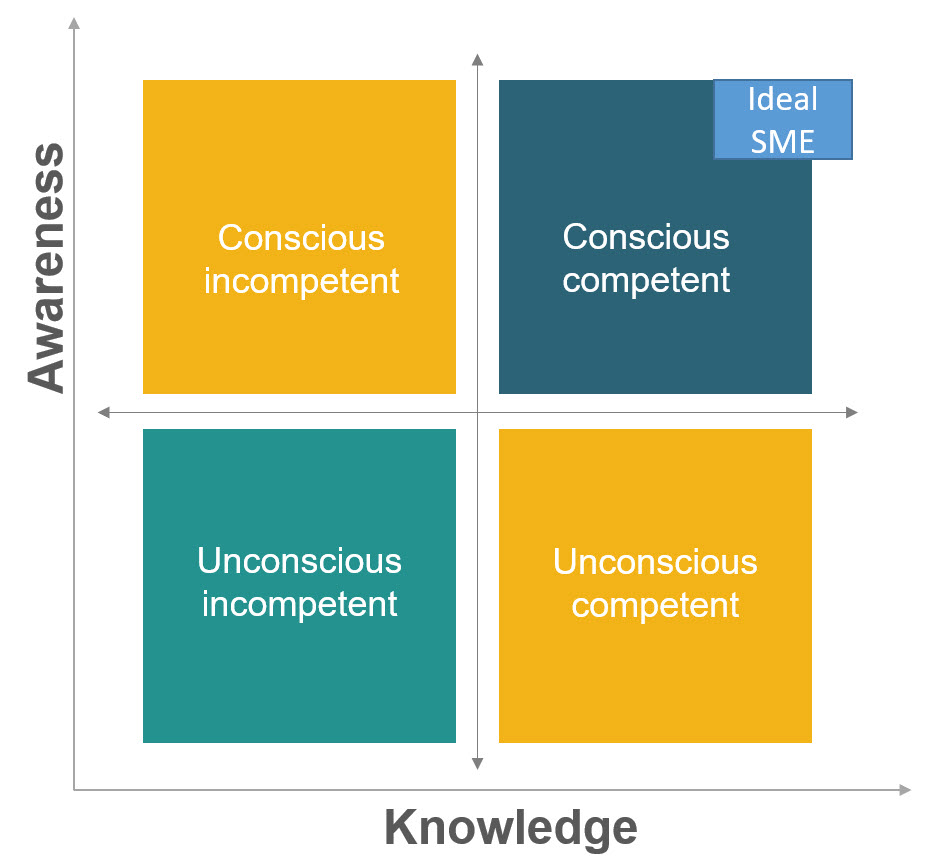

- Direct Experience: Students participate in activities that require them to apply what they have learned in a practical setting. An old adage is that you must do a job for three years before understanding it. However, you must keep going through the iterations since quality comprises multiple jobs. For example, my progress from deviation reviewer to eQMS implementation, to computer systems quality, to risk champion, to quality engineering, to change management process owner, to computer system implementor, to technology implementor, to validation quality, to operational excellence, to quality systems leader, to validation leader (and I am leaving a lot out). Layering and layering real experience again and again.

- Reflection: Reflection is a critical component of experiential learning. Most people don’t do that enough. The quality profession requires us to think about our experiences, analyze what we have learned, and consider how it applies to our work. Audits and inspections are interesting tools that can drive reflection when approached correctly.

- Active Participation: Quality professionals must be active agents in their learning process. They take initiative, make decisions, and are responsible for the outcomes of their actions. This active engagement helps to deepen their learning and develop critical thinking skills.

- Community Engagement: I joke about being able to tell what company some spent their formative years in. And that is not a good thing. Quality professionals need to seek out collaboration with the wider community members, often through professional organizations.

- Integration of Knowledge and Practice: Experiential fields bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. Quality professionals must integrate what they have studied with real-world experiences, enhancing their understanding and retention of the material. And then do it again.

The quality profession is a dynamic and interactive learning environment emphasizing learning by doing, reflecting, and applying knowledge in real-world contexts.