The persistent attribution of human error as a root cause deviations reveals far more about systemic weaknesses than individual failings. The label often masks deeper organizational, procedural, and cultural flaws. Like cracks in a foundation, recurring human errors signal where quality management systems (QMS) fail to account for the complexities of human cognition, communication, and operational realities.

The Myth of Human Error as a Root Cause

Regulatory agencies increasingly reject “human error” as an acceptable conclusion in deviation investigations. This shift recognizes that human actions occur within a web of systemic influences. A technician’s missed documentation step or a formulation error rarely stem from carelessness alone but emerge from:

- Procedural complexity: Overly complicated standard operating procedures (SOPs) that exceed working memory capacity

- Cognitive overload: High-stress environments where operators juggle competing priorities

- Latent system flaws: Poor equipment design, inadequate training reinforcement, or misaligned incentives

The aviation industry’s “Tower of Babel” problem—where siloed teams develop isolated communication loops—parallels pharmaceutical manufacturing. The Quality Unit may prioritize regulatory compliance, while production focuses on throughput, creating disjointed interpretations of “quality.” These disconnects manifest as errors when cross-functional risks go unaddressed.

Cognitive Architecture and Error Propagation

Human cognition operates under predictable constraints. Attentional biases, memory limitations, and heuristic decision-making—while evolutionarily advantageous—create vulnerabilities in GMP environments. For example:

- Attentional tunneling: An operator hyper-focused on solving a equipment jam may overlook a temperature excursion alert.

- Procedural drift: Subtle deviations from written protocols accumulate over time as workers optimize for perceived efficiency.

- Complacency cycles: Over-familiarity with routine tasks reduces vigilance, particularly during night shifts or prolonged operations.

These cognitive patterns aren’t failures but features of human neurobiology. Effective QMS design anticipates them through:

- Error-proofing: Automated checkpoints that detect deviations before critical process stages

- Cognitive load management: Procedures (including batch records) tailored to cognitive load principles with decision-support prompts

- Resilience engineering: Simulations that train teams to recognize and recover from near-misses

Strategies for Reframing Human Error Analysis

Conduct Cognitive Autopsies

Move beyond 5-Whys to adopt human factors analysis frameworks:

- Human Error Assessment and Reduction Technique (HEART): Quantifies the likelihood of specific error types based on task characteristics

- Critical Action and Decision (CAD) timelines: Maps decision points where system defenses failed

For example, a labeling mix-up might reveal:

- Task factors: Nearly identical packaging for two products (29% contribution to error likelihood)

- Environmental factors: Poor lighting in labeling area (18%)

- Organizational factors: Inadequate change control when adding new SKUs (53%)

Redesign for Intuitive Use

The redesign of for intuitive use requires multilayered approaches based on understand how human brains actually work. At the foundation lies procedural chunking, an evidence-based method that restructures complex standard operating procedures (SOPs) into digestible cognitive units aligned with working memory limitations. This approach segments multiphase processes like aseptic filling into discrete verification checkpoints, reducing cognitive overload while maintaining procedural integrity through sequenced validation gates. By mirroring the brain’s natural pattern recognition capabilities, chunked protocols demonstrate significantly higher compliance rates compared to traditional monolithic SOP formats.

Complementing this cognitive scaffolding, mistake-proof redesigns create inherent error detection mechanisms.

To sustain these engineered safeguards, progressive facilities implement peer-to-peer audit protocols during critical operations and transition periods.

Leverage Error Data Analytics

The integration of data analytics into organizational processes has emerged as a critical strategy for minimizing human error, enhancing accuracy, and driving informed decision-making. By leveraging advanced computational techniques, automation, and machine learning, data analytics addresses systemic vulnerabilities.

Human Error Assessment and Reduction Technique (HEART): A Systematic Framework for Error Mitigation

Benefits of the Human Error Assessment and Reduction Technique (HEART)

1. Simplicity and Speed: HEART is designed to be straightforward and does not require complex tools, software, or large datasets. This makes it accessible to organizations without extensive human factors expertise and allows for rapid assessments. The method is easy to understand and apply, even in time-constrained or resource-limited environments.

2. Flexibility and Broad Applicability: HEART can be used across a wide range of industries—including nuclear, healthcare, aviation, rail, process industries, and engineering—due to its generic task classification and adaptability to different operational contexts. It is suitable for both routine and complex tasks.

3. Systematic Identification of Error Influences: The technique systematically identifies and quantifies Error Producing Conditions (EPCs) that increase the likelihood of human error. This structured approach helps organizations recognize the specific factors—such as time pressure, distractions, or poor procedures—that most affect reliability.

4. Quantitative Error Prediction: HEART provides a numerical estimate of human error probability for specific tasks, which can be incorporated into broader risk assessments, safety cases, or design reviews. This quantification supports evidence-based decision-making and prioritization of interventions.

5. Actionable Risk Reduction: By highlighting which EPCs most contribute to error, HEART offers direct guidance on where to focus improvement efforts—whether through engineering redesign, training, procedural changes, or automation. This can lead to reduced error rates, improved safety, fewer incidents, and increased productivity.

6. Supports Accident Investigation and Design: HEART is not only a predictive tool but also valuable in investigating incidents and guiding the design of safer systems and procedures. It helps clarify how and why errors occurred, supporting root cause analysis and preventive action planning.

7. Encourages Safety and Quality Culture and Awareness: Regular use of HEART increases awareness of human error risks and the importance of control measures among staff and management, fostering a proactive culture.

When Is HEART Best Used?

- Risk Assessment for Critical Tasks: When evaluating tasks where human error could have severe consequences (e.g., operating nuclear control systems, administering medication, critical maintenance), HEART helps quantify and reduce those risks.

- Design and Review of Procedures: During the design or revision of operational procedures, HEART can identify steps most vulnerable to error and suggest targeted improvements.

- Incident Investigation: After an failure or near-miss, HEART helps reconstruct the event, identify contributing EPCs, and recommend changes to prevent recurrence.

- Training and Competence Assessment: HEART can inform training programs by highlighting the conditions and tasks where errors are most likely, allowing for focused skill development and awareness.

- Resource-Limited or Fast-Paced Environments: Its simplicity and speed make HEART ideal for organizations needing quick, reliable human error assessments without extensive resources or data.

Generic Task Types (GTTs): Establishing Baselines

HEART classifies human activities into nine Generic Task Types (GTT) with predefined nominal human error probabilities (NHEPs) derived from decades of industrial incident data:

| GTT Code | Task Description | Nominal HEP Range |

|---|---|---|

| A | Complex, novel tasks requiring problem-solving | 0.55 (0.35–0.97) |

| B | Shifting attention between multiple systems | 0.26 (0.14–0.42) |

| C | High-skill tasks under time constraints | 0.16 (0.12–0.28) |

| D | Rule-based diagnostics under stress | 0.09 (0.06–0.13) |

| E | Routine procedural tasks | 0.02 (0.007–0.045) |

| F | Restoring system states | 0.003 (0.0008–0.007) |

| G | Highly practiced routine operations | 0.0004 (0.00008–0.009) |

| H | Supervised automated actions | 0.00002 (0.000006–0.0009) |

| M | Miscellaneous/undefined tasks | 0.003 (0.008–0.11) |

Comprehensive Taxonomy of Error-Producing Conditions (EPCs)

HEART’s 38 Error Producing Conditionss represent contextual amplifiers of error probability, categorized under the 4M Framework (Man, Machine, Media, Management):

| EPC Code | Description | Max Effect | 4M Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unfamiliarity with task | 17× | Man |

| 2 | Time shortage | 11× | Management |

| 3 | Low signal-to-noise ratio | 10× | Machine |

| 4 | Override capability of safety features | 9× | Machine |

| 5 | Spatial/functional incompatibility | 8× | Machine |

| 6 | Model mismatch between mental and system states | 8× | Man |

| 7 | Irreversible actions | 8× | Machine |

| 8 | Channel overload (information density) | 6× | Media |

| 9 | Technique unlearning | 6× | Man |

| 10 | Inadequate knowledge transfer | 5.5× | Management |

| 11 | Performance ambiguity | 5× | Media |

| 12 | Misperception of risk | 4× | Man |

| 13 | Poor feedback systems | 4× | Machine |

| 14 | Delayed/incomplete feedback | 4× | Media |

| 15 | Operator inexperience | 3× | Man |

| 16 | Impoverished information quality | 3× | Media |

| 17 | Inadequate checking procedures | 3× | Management |

| 18 | Conflicting objectives | 2.5× | Management |

| 19 | Lack of information diversity | 2.5× | Media |

| 20 | Educational/training mismatch | 2× | Management |

| 21 | Dangerous incentives | 2× | Management |

| 22 | Lack of skill practice | 1.8× | Man |

| 23 | Unreliable instrumentation | 1.6× | Machine |

| 24 | Need for absolute judgments | 1.6× | Man |

| 25 | Unclear functional allocation | 1.6× | Management |

| 26 | No progress tracking | 1.4× | Media |

| 27 | Physical capability mismatches | 1.4× | Man |

| 28 | Low semantic meaning of information | 1.4× | Media |

| 29 | Emotional stress | 1.3× | Man |

| 30 | Ill-health | 1.2× | Man |

| 31 | Low workforce morale | 1.2× | Management |

| 32 | Inconsistent interface design | 1.15× | Machine |

| 33 | Poor environmental conditions | 1.1× | Media |

| 34 | Low mental workload | 1.1× | Man |

| 35 | Circadian rhythm disruption | 1.06× | Man |

| 36 | External task pacing | 1.03× | Management |

| 37 | Supernumerary staffing issues | 1.03× | Management |

| 38 | Age-related capability decline | 1.02× | Man |

HEP Calculation Methodology

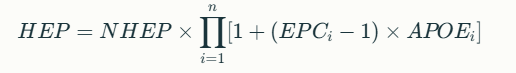

The HEART equation incorporates both multiplicative and additive effects of EPCs:

Where:

- NHEP: Nominal Human Error Probability from GTT

- EPC_i: Maximum effect of i-th EPC

- APOE_i: Assessed Proportion of Effect (0–1)

HEART Case Study: Operator Error During Biologics Drug Substance Manufacturing

A biotech facility was producing a monoclonal antibody (mAb) drug substance using mammalian cell culture in large-scale bioreactors. The process involved upstream cell culture (expansion and production), followed by downstream purification (protein A chromatography, filtration), and final bulk drug substance filling. The manufacturing process required strict adherence to parameters such as temperature, pH, and feed rates to ensure product quality, safety, and potency.

During a late-night shift, an operator was responsible for initiating a nutrient feed into a 2,000L production bioreactor. The standard operating procedure (SOP) required the feed to be started at 48 hours post-inoculation, with a precise flow rate of 1.5 L/hr for 12 hours. The operator, under time pressure and after a recent shift change, incorrectly programmed the feed rate as 15 L/hr rather than 1.5 L/hr.

Outcome:

- The rapid addition of nutrients caused a metabolic imbalance, leading to excessive cell growth, increased waste metabolite (lactate/ammonia) accumulation, and a sharp drop in product titer and purity.

- The batch failed to meet quality specifications for potency and purity, resulting in the loss of an entire production lot.

- Investigation revealed no system alarms for the high feed rate, and the error was only detected during routine in-process testing several hours later.

HEART Analysis

Task Definition

- Task: Programming and initiating nutrient feed in a GMP biologics manufacturing bioreactor.

- Criticality: Direct impact on cell culture health, product yield, and batch quality.

Generic Task Type (GTT)

| GTT Code | Description | Nominal HEP |

|---|---|---|

| E | Routine procedural task with checking | 0.02 |

Error-Producing Conditions (EPCs) Using the 5M Model

| 5M Category | EPC (HEART) | Max Effect | APOE | Example in Incident |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | Inexperience with new feed system (EPC15) | 3× | 0.8 | Operator recently trained on upgraded control interface |

| Machine | Poor feedback (no alarm for high feed rate, EPC13) | 4× | 0.7 | System did not alert on out-of-range input |

| Media | Ambiguous SOP wording (EPC11) | 5× | 0.5 | SOP listed feed rate as “1.5L/hr” in a table, not text |

| Management | Time pressure to meet batch deadlines (EPC2) | 11× | 0.6 | Shift was behind schedule due to earlier equipment delay |

| Milieu | Distraction during shift change (EPC36) | 1.03× | 0.9 | Handover occurred mid-setup, leading to divided attention |

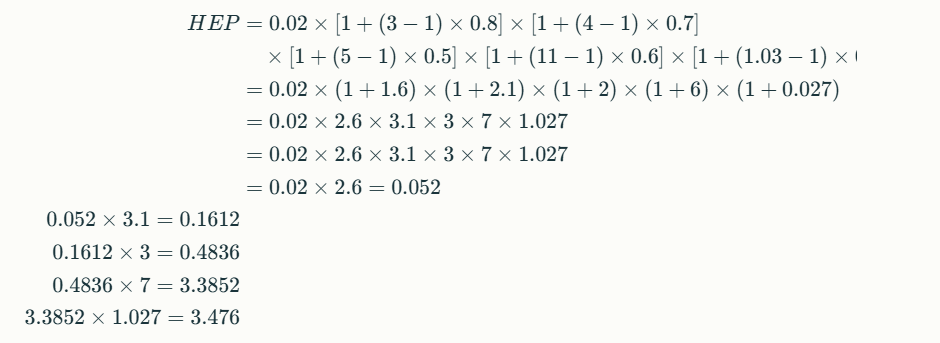

Human Error Probability (HEP) Calculation

HEP ≈ 3.5 (350%)

This extremely high error probability highlights a systemic vulnerability, not just an individual lapse.

Root Cause and Contributing Factors

- Operator: Recently trained, unfamiliar with new interface (Man)

- System: No feedback or alarm for out-of-spec feed rate (Machine)

- SOP: Ambiguous presentation of critical parameter (Media)

- Management: High pressure to recover lost time (Management)

- Environment: Shift handover mid-task, causing distraction (Milieu)

Corrective Actions

Technical Controls

- Automated Range Checks: Bioreactor control software now prevents entry of feed rates outside validated ranges and requires supervisor override for exceptions.

- Visual SOP Enhancements: Critical parameters are now highlighted in both text and tables, and reviewed during operator training.

Human Factors & Training

- Simulation-Based Training: Operators practice feed setup in a virtual environment simulating distractions and time pressure.

- Shift Handover Protocol: Critical steps cannot be performed during handover periods; tasks must be paused or completed before/after shift changes.

Management & Environmental Controls

- Production Scheduling: Buffer time added to schedules to reduce time pressure during critical steps.

- Alarm System Upgrade: Real-time alerts for any parameter entry outside validated ranges.

Outcomes (6-Month Review)

| Metric | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Feed rate programming errors | 4/year | 0/year |

| Batch failures (due to feed) | 2/year | 0/year |

| Operator confidence (survey) | 62/100 | 91/100 |

Lessons Learned

- Systemic Safeguards: Reliance on operator vigilance alone is insufficient in complex biologics manufacturing; layered controls are essential.

- Human Factors: Addressing EPCs across the 5M model—Man, Machine, Media, Management, Milieu—dramatically reduces error probability.

- Continuous Improvement: Regular review of near-misses and operator feedback is crucial for maintaining process robustness in biologics manufacturing.

This case underscores how a HEART-based approach, tailored to biologics drug substance manufacturing, can identify and mitigate multi-factorial risks before they result in costly failures.