This morning, an article landed in my inbox with the headline: “Why MES Remains the Digital Backbone, Even in Industry 5.0.” My immediate reaction? “You have got to be kidding me.” Honestly, that was also my second, third, and fourth reaction—each one a little more exasperated than the last. Sometimes, it feels like this relentless urge to slap a new number on every wave of technology is exactly why we can’t have nice things.

Curiosity got the better of me, though, and I clicked through. To my surprise, the article raised some interesting points. Still, I couldn’t help but wonder: do we really need another numbered revolution?

So, what exactly is Industry 5.0—and why is everyone talking about it? Let’s dig in.

The Origins and Evolution of Industry 5.0: From Japanese Society 5.0 to European Industrial Policy

The concept of Industry 5.0 emerged from a complex interplay of Japanese technological philosophy and European industrial policy, representing a fundamental shift from purely efficiency-driven manufacturing toward human-centric, sustainable, and resilient production systems. While the term “Industry 5.0” was formally coined by the European Commission in 2021, its intellectual foundations trace back to Japan’s Society 5.0 concept introduced in 2016, which envisioned a “super-smart society” that integrates cyberspace and physical space to address societal challenges. This evolution reflects a growing recognition that the Fourth Industrial Revolution’s focus on automation and digitalization, while transformative, required rebalancing to prioritize human welfare, environmental sustainability, and social resilience alongside technological advancement.

The Japanese Foundation: Society 5.0 as Intellectual Precursor

The conceptual roots of Industry 5.0 can be traced directly to Japan’s Society 5.0 initiative, which was first proposed in the Fifth Science and Technology Basic Plan adopted by the Japanese government in January 2016. This concept emerged from intensive deliberations by expert committees administered by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) since 2014. Society 5.0 was conceived as Japan’s response to the challenges of an aging population, economic stagnation, and the need to compete in the digital economy while maintaining human-centered values.

The Japanese government positioned Society 5.0 as the fifth stage of human societal development, following the hunter-gatherer society (Society 1.0), agricultural society (Society 2.0), industrial society (Society 3.0), and information society (Society 4.0). This framework was designed to address Japan’s specific challenges, including rapid population aging, social polarization, and depopulation in rural areas. The concept gained significant momentum when it was formally presented by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2019 and received robust support from the Japan Business Federation (Keidanren), which saw it as a pathway to economic revitalization.

International Introduction and Recognition

The international introduction of Japan’s Society 5.0 concept occurred at the CeBIT 2017 trade fair in Hannover, Germany, where the Japanese Business Federation presented this vision of digitally transforming society as a whole. This presentation marked a crucial moment in the global diffusion of ideas that would later influence the development of Industry 5.0. The timing was significant, as it came just six years after Germany had introduced the Industry 4.0 concept at the same venue in 2011, creating a dialogue between different national approaches to industrial and societal transformation.

The Japanese approach differed fundamentally from the German Industry 4.0 model by emphasizing societal transformation beyond manufacturing efficiency. While Industry 4.0 focused primarily on smart factories and cyber-physical systems, Society 5.0 envisioned a comprehensive integration of digital technologies across all aspects of society to create what Keidanren later termed an “Imagination Society”. This broader vision included autonomous vehicles and drones serving depopulated areas, remote medical consultations, and flexible energy systems tailored to specific community needs.

European Formalization and Policy Development

The formal conceptualization of Industry 5.0 as a distinct industrial paradigm emerged from the European Commission’s research and innovation activities. In January 2021, the European Commission published a comprehensive 48-page white paper titled “Industry 5.0 – Towards a sustainable, human-centric and resilient European industry,” which officially coined the term and established its core principles. This document resulted from discussions held in two virtual workshops organized in July 2020, involving research and technology organizations and funding agencies across Europe.

The European Commission’s approach to Industry 5.0 represented a deliberate complement to, rather than replacement of, Industry 4.0. According to the Commission, Industry 5.0 “provides a vision of industry that aims beyond efficiency and productivity as the sole goals, and reinforces the role and the contribution of industry to society”. This formulation explicitly placed worker wellbeing at the center of production processes and emphasized using new technologies to provide prosperity beyond traditional economic metrics while respecting planetary boundaries.

Policy Integration and Strategic Objectives

The European conceptualization of Industry 5.0 was strategically aligned with three key Commission priorities: “An economy that works for people,” the “European Green Deal,” and “Europe fit for the digital age”. This integration demonstrates how Industry 5.0 emerged not merely as a technological concept but as a comprehensive policy framework addressing multiple societal challenges simultaneously. The approach emphasized adopting human-centric technologies, including artificial intelligence regulation, and focused on upskilling and reskilling European workers to prepare for industrial transformation.

The European Commission’s framework distinguished Industry 5.0 by its explicit focus on three core values: sustainability, human-centricity, and resilience. This represented a significant departure from Industry 4.0’s primary emphasis on efficiency and productivity, instead prioritizing environmental responsibility, worker welfare, and system robustness against external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The Commission argued that this approach would enable European industry to play an active role in addressing climate change, resource preservation, and social stability challenges.

Conceptual Evolution and Theoretical Development

From Automation to Human-Machine Collaboration

The evolution from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0 reflects a fundamental shift in thinking about the role of humans in automated production systems. While Industry 4.0 emphasized machine-to-machine communication, Internet of Things connectivity, and autonomous decision-making systems, Industry 5.0 reintroduced human creativity and collaboration as central elements. This shift emerged from practical experiences with Industry 4.0 implementation, which revealed limitations in purely automated approaches and highlighted the continued importance of human insight, creativity, and adaptability.

Industry 5.0 proponents argue that the concept represents an evolution rather than a revolution, building upon Industry 4.0’s technological foundation while addressing its human and environmental limitations. The focus shifted toward collaborative robots (cobots) that work alongside human operators, combining the precision and consistency of machines with human creativity and problem-solving capabilities. This approach recognizes that while automation can handle routine and predictable tasks effectively, complex problem-solving, innovation, and adaptation to unexpected situations remain distinctly human strengths.

Academic and Industry Perspectives

The academic and industry discourse around Industry 5.0 has emphasized its role as a corrective to what some viewed as Industry 4.0’s overly technology-centric approach. Scholars and practitioners have noted that Industry 4.0’s focus on digitalization and automation, while achieving significant efficiency gains, sometimes neglected human factors and societal impacts. Industry 5.0 emerged as a response to these concerns, advocating for a more balanced approach that leverages technology to enhance rather than replace human capabilities.

The concept has gained traction across various industries as organizations recognize the value of combining technological sophistication with human insight. This includes applications in personalized manufacturing, where human creativity guides AI systems to produce customized products, and in maintenance operations, where human expertise interprerets data analytics to make complex decisions about equipment management416. The approach acknowledges that successful industrial transformation requires not just technological advancement but also social acceptance and worker engagement.

Timeline and Key Milestones

The development of Industry 5.0 can be traced through several key phases, beginning with Japan’s internal policy deliberations from 2014 to 2016, followed by international exposure in 2017, and culminating in European formalization in 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic played a catalytic role in accelerating interest in Industry 5.0 principles, as organizations worldwide experienced the importance of resilience, human adaptability, and sustainable practices in maintaining operations during crisis conditions.

The period from 2017 to 2020 saw growing academic and industry discussion about the limitations of purely automated approaches and the need for more human-centric industrial models. This discourse was influenced by practical experiences with Industry 4.0 implementation, which revealed challenges in areas such as worker displacement, skill gaps, and environmental sustainability. The European Commission’s workshops in 2020 provided a formal venue for consolidating these concerns into a coherent policy framework.

Contemporary Developments and Future Trajectory

Since the European Commission’s formal introduction of Industry 5.0 in 2021, the concept has gained international recognition and adoption across various sectors. The approach has been particularly influential in discussions about sustainable manufacturing, worker welfare, and industrial resilience in the post-pandemic era. Organizations worldwide are beginning to implement Industry 5.0 principles, focusing on human-machine collaboration, environmental responsibility, and system robustness.

The concept continues to evolve as practitioners gain experience with its implementation and as new technologies enable more sophisticated forms of human-machine collaboration. Recent developments have emphasized the integration of artificial intelligence with human expertise, the application of circular economy principles in manufacturing, and the development of resilient supply chains capable of adapting to global disruptions. These developments suggest that Industry 5.0 will continue to influence industrial policy and practice as organizations seek to balance technological advancement with human and environmental considerations.

Evaluating Industry 5.0 Concepts

While I am naturally suspicious of version numbers on frameworks, and certainly exhausted by the Industry 4.0/Quality 4.0 advocates, the more I read about industry 5.0 the more the core concepts resonated with me. Industry 5.0 challenges manufacturers to reshape how they think about quality, people, and technology. And this resonates on what has always been the fundamental focus of this blog: robust Quality Units, data integrity, change control, and the organizational structures needed for true quality oversight.

Human-Centricity: From Oversight to Empowerment

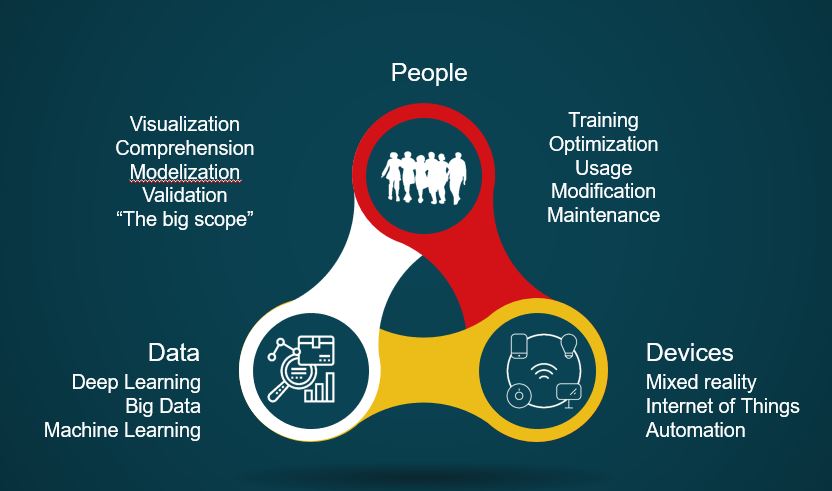

Industry 5.0’s defining feature is its human-centric approach, aiming to put people back at the heart of manufacturing. This aligns closely with my focus on decision-making, oversight, and continuous improvement.

Collaboration Between Humans and Technology

I frequently address the pitfalls of siloed teams and the dangers of relying solely on either manual or automated systems for quality management. Industry 5.0’s vision of human-machine collaboration—where AI and automation support, but don’t replace, expert judgment—mirrors this blog’s call for integrated quality systems.

Proactive, Data-Driven Quality

To say that a central theme in my career has been how reactive, paper-based, or poorly integrated systems lead to data integrity issues and regulatory citations would be an understatement. Thus, I am fully aligned with the advocacy for proactive, real-time management utilizing AI, IoT, and advanced analytics. This continued shift from after-the-fact remediation to predictive, preventive action directly addresses the recurring compliance gaps we continue to struggle with. This blog’s focus on robust documentation, risk-based change control, and comprehensive batch review finds a natural ally in Industry 5.0’s data-driven, risk-based quality management systems.

Sustainability and Quality Culture

Another theme on this blog is the importance of management support and a culture of quality—elements that Industry 5.0 elevates by integrating sustainability and social responsibility into the definition of quality itself. Industry 5.0 is not just about defect prevention; it’s about minimizing waste, ensuring ethical sourcing, and considering the broader impact of manufacturing on people and the planet. This holistic view expands the blog’s advocacy for independent, well-resourced Quality Units to include environmental and social governance as core responsibilities. Something I perhaps do not center as much in my practice as I should.

Democratic Leadership

The principles of democratic leadership explored extensively on this blog provide a critical foundation for realizing the human-centric aspirations of Industry 5.0. Central to the my philosophy is decentralizing decision-making and fostering psychological safety—concepts that align directly with Industry 5.0’s emphasis on empowering workers through collaborative human-machine ecosystems. By advocating for leadership models that distribute authority to frontline employees and prioritize transparency, this blog’s framework mirrors Industry 5.0’s rejection of rigid hierarchies in favor of agile, worker-driven innovation. The emphasis on equanimity—maintaining composed, data-driven responses to quality challenges—resonates with Industry 5.0’s vision of resilient systems where human judgment guides AI and automation. This synergy is particularly evident in the my analysis of decentralized decision-making, which argues that empowering those closest to operational realities accelerates problem-solving while building ownership—a necessity for Industry 5.0’s adaptive production environments. The European Commission’s Industry 5.0 white paper explicitly calls for this shift from “shareholder to stakeholder value,” a transition achievable only through the democratic leadership practices championed in the blog’s critique of Taylorist management models. By merging technological advancement with human-centric governance, this blog’s advocacy for flattened hierarchies and worker agency provides a blueprint for implementing Industry 5.0’s ideals without sacrificing operational rigor.

Convergence and Opportunity

While I have more than a hint of skepticism about the term Industry 5.0, I acknowledge its reliance on the foundational principles that I consider crucial to quality management. By integrating robust organizational quality structures, empowered individuals, and advanced technology, manufacturers can transcend mere compliance to deliver sustainable, high-quality products in a rapidly evolving world. For quality professionals, the implication is clear: the future is not solely about increased automation or stricter oversight but about more intelligent, collaborative, and, importantly, human-centric quality management. This message resonates deeply with me, and it should with you as well, as it underscores the value and importance of our human contribution in this process.

Key Sources on Industry 5.0

Here is a curated list of foundational and authoritative sources for understanding Industry 5.0, including official reports, academic articles, and expert analyses that I found most helpful when evaluating the concept of Industry 5.0:

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation: “Industry 5.0: Towards a sustainable, human-centric and resilient European industry” (2021)

- The seminal report that formally introduces and defines Industry 5.0, outlining its pillars and societal vision.

- TWI Global: “What is Industry 5.0? (Top 5 Things You Need To Know)“

- An accessible overview of Industry 5.0, its technologies, and its human-centric approach.

- Automation.com: “The Three Pillars of Industry 5.0“

- Explains the central pillars—human focus, sustainability, and resiliency—and their practical implications for organizations.

- Forbes: “What Is Industry 5.0 And How It Will Radically Change Your Business Strategy?” by Jeroen Kraaijenbrink

- Discusses the shift from economic to societal value and the broader strategic implications of Industry 5.0.

- ScienceDirect: “Industry 5.0: A new strategy framework for sustainability“

- Presents a novel framework for manufacturing strategy in the Industry 5.0 paradigm, with academic rigor and case studies.

- ScienceDirect: “Industry 5.0 – Past, Present, and Near Future“

- A scholarly review of the evolution, current research trends, and future directions of Industry 5.0, with links to further academic literature.

- Grand View Research: “Industry 5.0 Market Size & Share | Industry Report, 2030“

- Provides market analysis, trends, and forecasts related to Industry 5.0 technologies and adoption.

- UNESCO: “Japan pushing ahead with Society 5.0 to overcome chronic social challenges”

- Explores the Japanese Society 5.0 initiative, which heavily influenced the development of Industry 5.0 concepts.

- Eviden: “How Industry 5.0 puts values first“

- Focuses on the value-driven evolution of Industry 5.0, highlighting its impact on people, sustainability, and resilience.

- Proaction International Blog: “Industry 5.0: Revolutionizing Work by Putting People First“

- Explores the people-centric transformation of work and management under Industry 5.0.