The October 2025 Warning Letter to Apotex Inc. is fascinating not because it reveals anything novel about FDA expectations, but because it exposes the chasm between what we know we should do and what we actually allow to happen on our watch. Evaluate it together with what we are seeing for Complete Response Letter (CRL) data, we can see that companies continue to struggle with the concept of equipment lifecycle management.

This isn’t about a few leaking gloves or deteriorated gaskets. This is about systemic failure in how we conceptualize, resource, and execute equipment management across the entire GMP ecosystem. Let me walk you through what the Apotex letter really tells us, where the FDA is heading next, and why your current equipment qualification program is probably insufficient.

The Apotex Warning Letter: A Case Study in Lifecycle Management Failure

The FDA’s Warning Letter to Apotex (WL: 320-26-12, October 31, 2025) reads like a checklist of every equipment lifecycle management failure I’ve witnessed in two decades of quality oversight. The agency cited 21 CFR 211.67(a) equipment maintenance failures, 21 CFR 211.192 inadequate investigations, and 21 CFR 211.113(b) aseptic processing deficiencies. But these citations barely scratch the surface of what actually went wrong.

The Core Failures: A Pattern of Deferral and Neglect

Between September 2023 and April 2025—18 months—Apotex experienced at least eight critical equipment failures during leak testing. Their personnel responded by retesting until they achieved passing results rather than investigating root causes. Think about that timeline. Eight failures over 18 months means a failure every 2-3 months, each one representing a signal that their equipment was degrading. When investigators finally examined the system, they found over 30 leaking areas. This wasn’t a single failure; this was systemic equipment deterioration that the organization chose to work around rather than address.

The letter documents white particle buildup on manufacturing equipment surfaces, particles along conveyor systems, deteriorated gasket seals, and discolored gloves. Investigators observed a six-millimeter glove breach that was temporarily closed with a cable tie before production continued. They found tape applied to “false covers” as a workaround. These aren’t just housekeeping issues—they’re evidence that Apotex had crossed from proactive maintenance into reactive firefighting, and then into dangerous normalization of deviation.

Most damning: Apotex had purchased upgraded equipment nearly a year before the FDA inspection but continued using the deteriorating equipment that was actively generating particles contaminating their nasal spray products. They had the solution in their possession. They chose not to implement it.

The Investigation Gap: Equipment Failures as Quality System Failures

The FDA hammered Apotex on their failure to investigate, but here’s what’s really happening: equipment failures are quality system failures until proven otherwise. When a leak happens , you don’t just replace whatever component leaked. You ask:

- Why did this component fail when others didn’t?

- Is this a batch-specific issue or a systemic supplier problem?

- How many products did this breach potentially affect?

- What does our environmental monitoring data tell us about the timeline of contamination?

- Are our maintenance intervals appropriate?

Apotex’s investigators didn’t ask these questions. Their personnel retested until they got passing results—a classic example of “testing into compliance” that I’ve seen destroy quality cultures. The quality unit failed to exercise oversight, and management failed to resource proper root cause analysis. This is what happens when quality becomes a checkbox exercise rather than an operational philosophy.

BLA CRL Trends: The Facility Equipment Crisis Is Accelerating

The Apotex warning letter doesn’t exist in isolation. It’s part of a concerning trend in FDA enforcement that’s becoming impossible to ignore. Facility inspection concerns dominate CRL justifications. Manufacturing and CMC deficiencies account for approximately 44% of all CRLs. For biologics specifically, facility-related issues are even more pronounced.

The Biologics-Specific Challenge

Biologics license applications face unique equipment lifecycle scrutiny. The 2024-2025 CRL data shows multiple biosimilars rejected due to third-party manufacturing facility issues despite clean clinical data. Tab-cel (tabelecleucel) received a CRL citing problems at a contract manufacturing organization—the FDA rejected an otherwise viable therapy because the facility couldn’t demonstrate equipment control.

This should terrify every biotech quality leader. The FDA is telling us: your clinical data is worthless if your equipment lifecycle management is suspect. They’re not wrong. Biologics manufacturing depends on consistent equipment performance in ways small molecule chemistry doesn’t. A 0.2°C deviation in a bioreactor temperature profile, caused by a poorly maintained chiller, can alter glycosylation patterns and change the entire safety profile of your product. The agency knows this, and they’re acting accordingly.

The Top 10 Facility Equipment Deficiencies Driving CRLs

Genesis AEC’s analysis of 200+ CRLs identified consistent equipment lifecycle themes:

- Inadequate Facility Segregation and Flow (cross-contamination risks from poor equipment placement)

- Missing or Incomplete Commissioning & Qualification (especially HVAC, WFI, clean steam systems)

- Fire Protection and Hazardous Material Handling Deficiencies (equipment safety systems)

- Critical Utility System Failures (WFI loops with dead legs, inadequate sanitization)

- Environmental Monitoring System Gaps (manual data recording, lack of 21 CFR Part 11 compliance)

- Container Closure and Packaging Validation Issues (missing extractables/leachables data, CCI testing gaps)

- Inadequate Cleanroom Classification and Control (ISO 14644 and EU Annex 1 compliance failures)

- Lack of Preventive Maintenance and Asset Management (missing calibration records, unclear maintenance responsibilities)

- Inadequate Documentation and Change Control (HVAC setpoint changes without impact assessment)

- Sustainability and Environmental Controls Overlooked (temperature/humidity excursions affecting product stability)

Notice what’s not on this list? Equipment selection errors. The FDA isn’t seeing companies buy the wrong equipment. They’re seeing companies buy the right equipment and then fail to manage it across its lifecycle. This is a crucial distinction. The problem isn’t capital allocation—it’s operational execution.

FDA’s Shift to “Equipment Lifecycle State of Control”

The FDA has introduced a significant conceptual shift in how they discuss equipment management. The Apotex Warning Letter is part of the agency’s new emphasis on “equipment lifecycle state of control” . This isn’t just semantic gamesmanship. It represents a fundamental understanding that discrete qualification events are not enough and that continuous lifecycle management is long overdue.

What “State of Control” Actually Means

Traditional equipment qualification followed a linear path: DQ → IQ → OQ → PQ → periodic requalification. State of control means:

- Continuous monitoring of equipment performance parameters, not just periodic checks

- Predictive maintenance based on performance data, not just manufacturer-recommended intervals

- Real-time assessment of equipment degradation signals (particle generation, seal wear, vibration changes)

- Integrated change management that treats equipment modifications as potential quality events

- Traceable decision-making about when to repair, refurbish, or retire equipment

The FDA is essentially saying: qualification is a snapshot; state of control is a movie. And they want to see the entire film, not just the trailer.

This aligns perfectly with the agency’s broader push toward Quality Management Maturity. As I’ve previously written about QMM, the FDA is moving away from checking compliance boxes and toward evaluating whether organizations have the infrastructure, culture, and competence to manage quality dynamically. Equipment lifecycle management is the perfect test case for this shift because equipment degradation is inevitable, predictable, and measurable. If you can’t manage equipment lifecycle, you can’t manage quality.

Global Regulatory Convergence: WHO, EMA, and PIC/S Perspectives

The FDA isn’t operating in a vacuum. Global regulators are converging on equipment lifecycle management as a critical inspection focus, though their approaches differ in emphasis.

EMA: The Annex 15 Lifecycle Approach

EMA’s process validation guidance explicitly requires IQ, OQ, and PQ for equipment and facilities as part of the validation lifecycle. Unlike FDA’s three-stage process validation model, EMA frames qualification as ongoing throughout the product lifecycle. Their 2023 revision of Annex 15 emphasizes:

- Validation Master Plans that include equipment lifecycle considerations

- Ongoing Process Verification that incorporates equipment performance data

- Risk-based requalification triggered by changes, deviations, or trends

- Integration with Product Quality Reviews (PQRs) to assess equipment impact on product quality

The EMA expects you to prove your equipment remains qualified through annual PQRs and continuous data review having been more explicit about a lifecycle approach for years.

PIC/S: The Change Management Imperative

PIC/S PI 054-1 on change management provides crucial guidance on equipment lifecycle triggers. The document explicitly identifies equipment upgrades as changes that require formal assessment, planning, and implementation controls. Critically, PIC/S emphasizes:

- Interim controls when equipment issues are identified but not yet remediated

- Post-implementation monitoring to ensure changes achieve intended risk reduction

- Documentation of rejected changes, especially those related to quality/safety hazard mitigation

The Apotex case is a PIC/S textbook violation: they identified equipment deterioration (hazard), purchased upgraded equipment (change proposal), but failed to implement it with appropriate interim controls or timeline management. The result was continued production with deteriorating equipment—exactly what PIC/S guidance is designed to prevent.

WHO: The Resource-Limited Perspective

WHO’s equipment lifecycle guidance, while focused on medical equipment in low-resource settings, offers surprisingly relevant insights for GMP facilities. Their framework emphasizes:

- Planning based on lifecycle cost, not just purchase price

- Skill development and training as core lifecycle components

- Decommissioning protocols that ensure data integrity and product segregation

The WHO model is refreshingly honest about resource constraints, which applies to many GMP facilities facing budget pressure. Their key insight: proper lifecycle management actually reduces total cost of ownership by 3-10x compared to run-to-failure approaches. This is the business case that quality leaders need to make to CFOs who view maintenance as a cost center.

The Six-System Inspection Model: Where Equipment Lifecycle Fits

FDA’s Six-System Inspection Model—particularly the Facilities and Equipment System—provides the structural framework for understanding equipment lifecycle requirements. As I’ve previously written, this system “ensures that facilities and equipment are suitable for their intended use and maintained properly” with focus on “design, maintenance, cleaning, and calibration.”

The Interconnectedness Problem

Here’s where many organizations fail: they treat the six systems as silos. Equipment lifecycle management bleeds across all of them:

- Production System: Equipment performance directly impacts process capability

- Laboratory Controls: Analytical equipment lifecycle affects data integrity

- Materials System: Equipment changes can affect raw material compatibility

- Packaging and Labeling: Equipment modifications require revalidation

- Quality System: Equipment deviations trigger CAPA and change control

The Apotex warning letter demonstrates this interconnectedness perfectly. Their equipment failures (Facilities & Equipment) led to container-closure integrity issues (Packaging), which they failed to investigate properly (Quality), resulting in distributed product that was potentially adulterated (Production). The FDA’s response required independent assessments of investigations, CAPA, and change management—three separate systems all impacted by equipment lifecycle failures.

The “State of Control” Assessment Questions

If FDA inspectors show up tomorrow, here’s what they’ll ask about your equipment lifecycle management:

- Design Qualification: Do your User Requirements Specifications include lifecycle maintenance requirements? Are you specifying equipment with modular upgrade paths, or are you buying disposable assets?

- Change Management: When you purchase upgraded equipment, what triggers its implementation? Is there a formal risk assessment linking equipment deterioration to product quality? Or do you wait for failures?

- Preventive Maintenance: Are your PM intervals based on manufacturer recommendations, or on actual performance data? Do you have predictive maintenance programs using vibration analysis, thermal imaging, or particle counting?

- Decommissioning: When equipment reaches end-of-life, do you have formal retirement protocols that assess data integrity impact? Or does old equipment sit in corners of the cleanroom “just in case”?

- Training: Do your operators understand equipment lifecycle concepts? Can they recognize early degradation signals? Or do they just call maintenance when something breaks?

These aren’t theoretical questions. They’re directly from recent 483 observations and CRL deficiencies.

The Business Case: Why Equipment Lifecycle Management Is Economic Imperative

Let’s be blunt: the pharmaceutical industry has treated equipment as a capital expense to be minimized, not an asset to be optimized. This is catastrophically wrong. The Apotex warning letter shows the true cost of this mindset:

- Product recalls: Multiple ophthalmic and oral solutions recalled

- Production suspension: Sterile manufacturing halted

- Independent assessments: Required third-party evaluation of entire quality system

- Reputational damage: Public warning letter, potential import alert

- Opportunity cost: Products stuck in regulatory limbo while competitors gain market share

Contrast this with the investment required for proper lifecycle management:

- Predictive maintenance systems: $50,000-200,000 for sensors and software

- Enhanced training programs: $10,000-30,000 annually

- Lifecycle documentation systems: $20,000-100,000 implementation

- Total: Less than the cost of a single batch recall

The ROI is undeniable. Equipment lifecycle management isn’t a cost center—it’s risk mitigation with quantifiable financial returns.

The CFO Conversation

I’ve had this conversation with CFOs more times than I can count. Here’s what works:

Don’t say: “We need more maintenance budget.”

Say: “Our current equipment lifecycle risk exposure is $X million based on recent CRL trends and warning letters. Investing $Y in lifecycle management reduces that risk by Z% and extends asset utilization by 2-3 years, deferring $W million in capital expenditures.”

Bring data. Show them the Apotex letter. Show them the Tab-cel CRL. Show them the 51 CRLs driven by facility concerns. CFOs understand risk-adjusted returns. Frame equipment lifecycle management as portfolio risk management, not engineering overhead.

Practical Framework: Building an Equipment Lifecycle Management Program

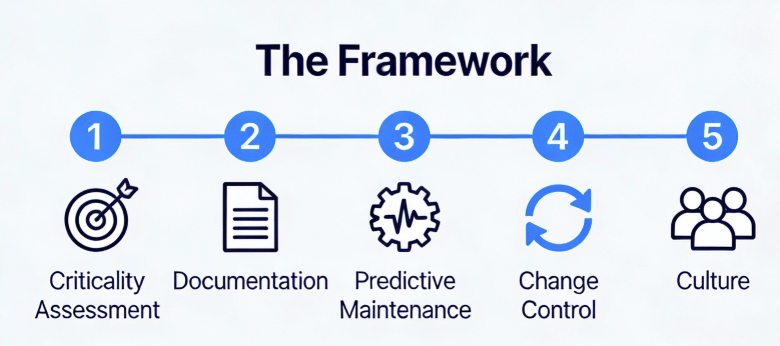

Enough theory. Here’s the practical framework I’ve implemented across multiple DS facilities, refined through inspections, and validated against regulatory expectations.

Phase 1: Asset Criticality Assessment

Not all equipment deserves equal lifecycle attention. Use a risk-based approach:

Criticality Class A (Direct Impact): Equipment whose failure directly impacts product quality, safety, or efficacy. Bioreactors, purification skids, sterile filling lines, environmental monitoring systems. These require full lifecycle management including continuous monitoring, predictive maintenance, and formal retirement protocols.

Criticality Class B (Indirect Impact): Equipment whose failure impacts GMP environment but not direct product attributes. HVAC units, WFI systems, clean steam generators. These require enhanced lifecycle management with robust PM programs and performance trending.

Criticality Class C (No Impact): Non-GMP equipment. Standard maintenance practices apply.

Phase 2: Lifecycle Documentation Architecture

Create a master equipment lifecycle file for each Class A and B asset containing:

- User Requirements Specification with lifecycle maintenance requirements

- Design Qualification including maintainability and upgrade path assessment

- Commissioning Protocol (IQ/OQ/PQ) with acceptance criteria that remain valid throughout lifecycle

- Maintenance Master Plan defining PM intervals, spare parts strategy, and predictive monitoring

- Performance Trending Protocol specifying parameters to monitor, alert limits, and review frequency

- Change Management History documenting all modifications with impact assessment

- Retirement Protocol defining end-of-life triggers and data migration requirements

As I’ve written about in my posts on GMP-critical systems, documentation must be living documents that evolve with the asset, not static files that gather dust after qualification.

Phase 3: Predictive Maintenance Implementation

Move beyond manufacturer-recommended intervals to condition-based maintenance:

- Vibration analysis for rotating equipment (pumps, agitators)

- Thermal imaging for electrical systems and heat transfer equipment

- Particle counting for cleanroom equipment and filtration systems

- Pressure decay testing for sterile barrier systems

- Oil analysis for hydraulic and lubrication systems

The goal is to detect degradation 6-12 months before failure, allowing planned intervention during scheduled shutdowns.

Phase 4: Integrated Change Control

Equipment changes must flow through formal change control with:

- Technical assessment by engineering and quality

- Risk evaluation using FMEA or similar tools

- Regulatory assessment for potential prior approval requirements

- Implementation planning with interim controls if needed

- Post-implementation review to verify effectiveness

The Apotex case shows what happens when you skip the interim controls. They identified the need for upgraded equipment (change) but failed to implement the necessary bridge measures to ensure product quality while waiting for that equipment to come online. They allowed the “future state” (new equipment) to become an excuse for neglecting the “current state” (deteriorating equipment).

This is a failure of Change Management Logic. In a robust quality system, the moment you identify that equipment requires replacement due to performance degradation, you have acknowledged a risk. If you cannot replace it immediately—due to capital cycles, lead times, or qualification timelines—you must implement interim controls to mitigate that risk.

For Apotex, those interim controls should have been:

- Reduced run durations to minimize stress on failing seals.

- Increased sampling plans (e.g., 100% leak testing verification or enhanced AQLs).

- Shortened maintenance intervals (replacing gaskets every batch instead of every campaign).

- Enhanced environmental monitoring focused specifically on the degrade zones.

Instead, they did nothing. They continued business as usual, likely comforting themselves with the purchase order for the new machine. The FDA’s response was unambiguous: A purchase order is not a CAPA. Until the new equipment is qualified and operational, your legacy equipment must remain in a state of control, or production must stop. There is no regulatory “grace period” for deteriorating assets.

Phase 5: The Cultural Shift—From “Repair” to “Reliability”

The final and most difficult phase of this framework is cultural. You cannot write a SOP for this; you have to lead it.

Most organizations operate on a “Break-Fix” mentality:

- Equipment runs until it alarms or fails.

- Maintenance fixes it.

- Quality investigates (or papers over) the failure.

- Production resumes.

The FDA’s “Lifecycle State of Control” demands a “Predict-Prevent” mentality:

- Equipment is monitored for degradation signals (vibration, heat, particle counts).

- Maintenance intervenes before failure limits are reached.

- Quality reviews trends to confirm the intervention was effective.

- Production continues uninterrupted.

To achieve this, you need to change how you incentivize your teams. Stop rewarding “heroic” fixes at 2 AM. Start rewarding the boring, invisible work of preventing the failure in the first place. As I’ve written before regarding Quality Management Maturity (QMM), mature quality systems are quiet systems. Chaos is not a sign of hard work; it’s a sign of lost control.

Conclusion: The Choice Before Us

The warning letter to Apotex Inc. and the rising tide of facility-related CRLs are not random compliance noise. They are signal flares. The regulatory expectations for equipment management have fundamentally shifted from static qualification (Is it validated?) to dynamic lifecycle management (Is it in a state of control right now?).

The FDA, EMA, and PIC/S have converged on a single truth: You cannot assure product quality if you cannot guarantee equipment performance.

We are at an inflection point. The industry’s aging infrastructure, combined with the increasing complexity of biologic processes and the unforgiving nature of residue control, has created a perfect storm. We can no longer treat equipment maintenance as a lower-tier support function. It is a core GMP activity, equal in criticality to batch record review or sterility testing.

As Quality Leaders, we have two choices:

- The Apotex Path: Treat equipment upgrades as capital headaches to be deferred. Ignore the “minor” leaks and “insignificant” residues. Let the maintenance team bandage the wounds while we focus on “strategic” initiatives. This path leads to 483s, warning letters, CRLs, and the excruciating public failure of seeing your facility’s name in an FDA press release.

- The Lifecycle Path: Embrace the complexity. Resource the predictive maintenance programs. Validate the residue removal. Treat every equipment change as a potential risk to patient safety. Build a system where equipment reliability is the foundation of your quality strategy, not an afterthought.

The second path is expensive. It is technically demanding. It requires fighting for budget dollars that don’t have immediate ROI. But it allows you to sleep at night, knowing that when—not if—the FDA investigator asks to see your equipment maintenance history, you won’t have to explain why you used a cable tie to fix a glove port.

You’ll simply show them the data that proves you’re in control.

Choose wisely.