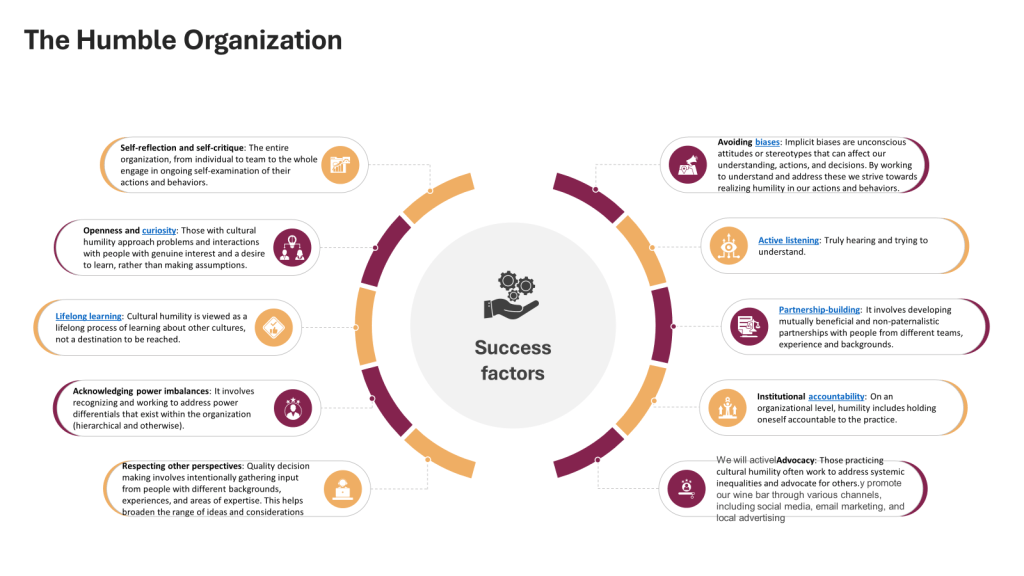

Cultural humility is an important part of Quality Culture. Cultural humility is often seen as approaching interactions with an attitude of openness, asking questions to learn rather than making assumptions, being willing to admit what you don’t know, and constantly examining your own lens and biases. It’s about creating an environment where all perspectives are valued and people feel respected.

Cultural humility involves several key characteristics and behaviors:

- Self-reflection and self-critique: The entire organization, from individual to team to the whole engage in ongoing self-examination of their actions and behaviors.

- Openness and curiosity: Those with cultural humility approach problems and interactions with people with genuine interest and a desire to learn, rather than making assumptions.

- Lifelong learning: Cultural humility is viewed as a lifelong process of learning about other cultures, not a destination to be reached.

- Acknowledging power imbalances: It involves recognizing and working to address power differentials that exist within the organization (hierarchical and otherwise).

- Respecting other perspectives: Quality decision making involves intentionally gathering input from people with different backgrounds, experiences, and areas of expertise. This helps broaden the range of ideas and considerations

- Avoiding biases: Implicit biases are unconscious attitudes or stereotypes that can affect our understanding, actions, and decisions. By working to understand and address these we strive towards realizing humility in our actions and behaviors.

- Active listening: Truly hearing and trying to understand.

- Partnership-building: It involves developing mutually beneficial and non-paternalistic partnerships with people from different teams, experience and backgrounds.

- Institutional accountability: On an organizational level, humility includes holding oneself accountable to the practice.

- Advocacy: Those practicing cultural humility often work to address systemic inequalities and advocate for others.

Leadership Behaviors

Humble leaders exhibit the following behaviors:

- Admitting limitations and mistakes

- Appreciating others’ strengths and contributions

- Being open to new ideas and feedback

- Listening before speaking

- Encouraging employees to keep trying and viewing mistakes as learning opportunities

- Taking responsibility for employees’ mistakes

- Modeling openness and fallibility

- Maintaining a collective focus

Cultural Attributes

A work culture with humble leadership is characterized by:

- Openness to new ideas and continuous learning

- Appreciation for diverse perspectives and contributions

- Reduced fear of taking interpersonal risks

- High-quality interpersonal relationships

- Collective humility within teams

- Trust between leaders and team members

- Inclusivity and reduced power differentials

- Emphasis on growth and development rather than blame

Employee Perceptions and Behaviors

In a humble environment, employees are more likely to:

- Feel safe expressing themselves and taking risks

- Believe in their ability to contribute constructively

- Engage in voice behaviors and share ideas

- Show themselves freely without fear of adverse consequences

- Imitate leaders in showing their own shortcomings and appreciating others

- Perceive making mistakes as acceptable

- Experience increased job satisfaction and reduced turnover intentions

Organizational Practices

To cultivate humility and psychological safety, organizations can:

- Develop policies and practices that promote diversity, equity, and inclusion

- Create an inclusive climate for errors and mutual assistance

- Implement leadership development programs focused on humble behaviors

- Encourage open dialogue and social relationships in teams

- Foster an error management climate that doesn’t punish mistakes but learns from them