The Pharmaceutical GMP Professional certification from the ASQ body of knowledge has, as its first area, Regulatory Agency governance, as it should, as a solid understanding of not only what the regulations and guidances say is important, it is pretty important to understand the why, and how they work together.

The subsection Regulations and Guidances states: “Interpret frequently used regulations and guidelines/guidances, including those published or administered by the Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention and Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme (PIC/S), Health Canada, the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the Food & Drug Administration (FDA), the USDA 9CFR, the International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council (IPEC), and Controlled Substance Act (CSA) 21 CFR 1300. (Understand)”

The ICH is on my mind this week as I’ve had a few different conversations with folks as part of development conversations and other places about understanding regulations, and this post is my jotting down a few thoughts for future development and thought.

I am focusing on Q7 to Q14 (Q7-Q11 are published, Q12 in draft, Q13 and Q14 just recently announced). There are other Qs and there are certainly other aspects of the ICH, those just are not what I am interested in here.

Q7-Q14, in many ways, involves the development of a philosophy between the ICH member nations and the various observers. Like any harmonization and guidance process, it has a few difficulties, but the developing philosophy has been developed to establish a more proactive and risk-based approach to the industry. As such, being well versed in the principles is good for a pharmaceutical quality practitioner.

Q7

ICHQ7 “Good Manufacturing Practice Guide for Active Pharmaceutical” was a fairly late product of the ICH. Founded in 1990 it was not until 1998 that it was determined that a GMP document was needed. It took another 2 years to complete and then another year or two for adoption by the member nations of the time. Which for the ICH is rocket speed.

Q7 is basically a solid list of what makes a functioning pharmaceutical quality system. Its the great big giant check-box of stuff to make sure you have. Personnel Qualification! Check! Production Controls? Check! Cleaning Validation? Check (well….)

Q7 covers API and has a great table on page 3 that covers applicability for types of API and the increasing GMPs. That said, Q7 is pretty much a great stopping place for anyone evaluating their quality system in a GMP environment. Most of the principles are universal, for example stating about master production records “These records should be numbered with a unique batch or identification number, dated and signed when issued. In continuous production, the product code together with the date and time can serve as the unique identifier until the final number is allocated.”

The Q&A released for Q7 in 2015 is telling. It is either all narrow specifies (including a definition of terms) or it is “Can I use risk management with X”, such as “To what extent can quality risk management be used in establishing appropriate containment measures to prevent cross-contamination?” To which the answer is basically “That is why we wrote Q9”

A good document to have around when setting standards.

Q8

ICHQ8 “Pharmaceutical Development” is the place where quality by design really starts coming into its own a solid concept. Finalized in 2005, it started being adopted in 2009/2010 (with Canada adopting it in 2016).

Q8 is all about setting forth a systematic, knowledge-driven, proactive, science and risk-based approach to pharmaceutical development. And at its heart, this is the philosophy that these ICH guidances rest on.

Q9

ICHQ9 “Quality Risk Management” was finalized in 2005 and quickly adopted in 2006 (except in Canada). This guidance pretty much recognizes that nothing the ICH was going to do would work without a risk-based approach, and it is arguable that the pharma industry might not have been all on the ball yet about risk. Risk management is without a doubt the glue that holds together the whole endeavor.

Q10

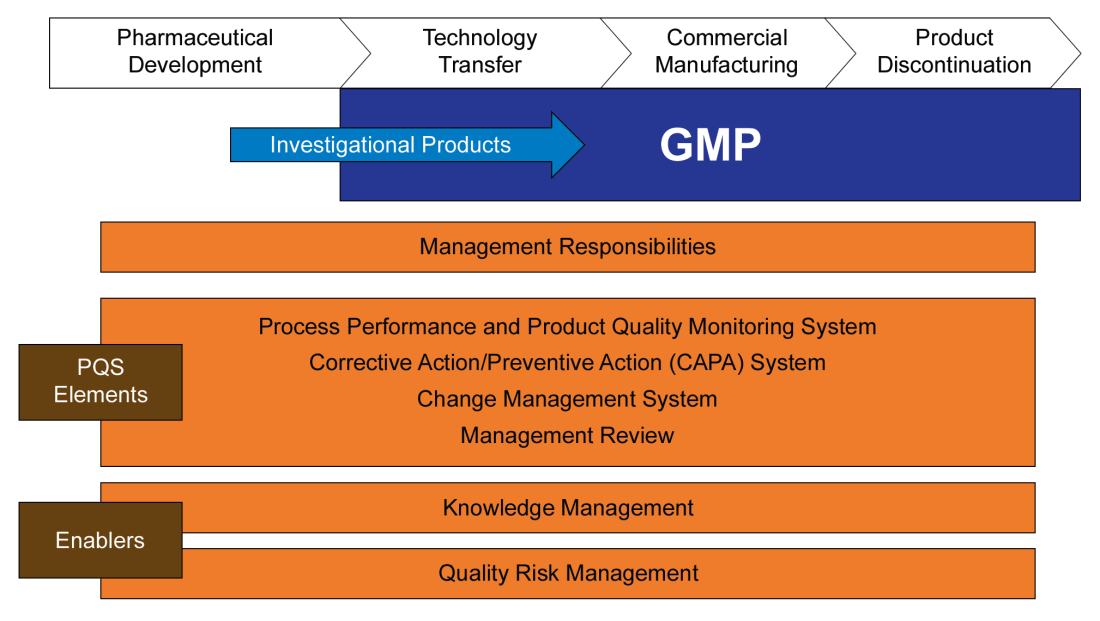

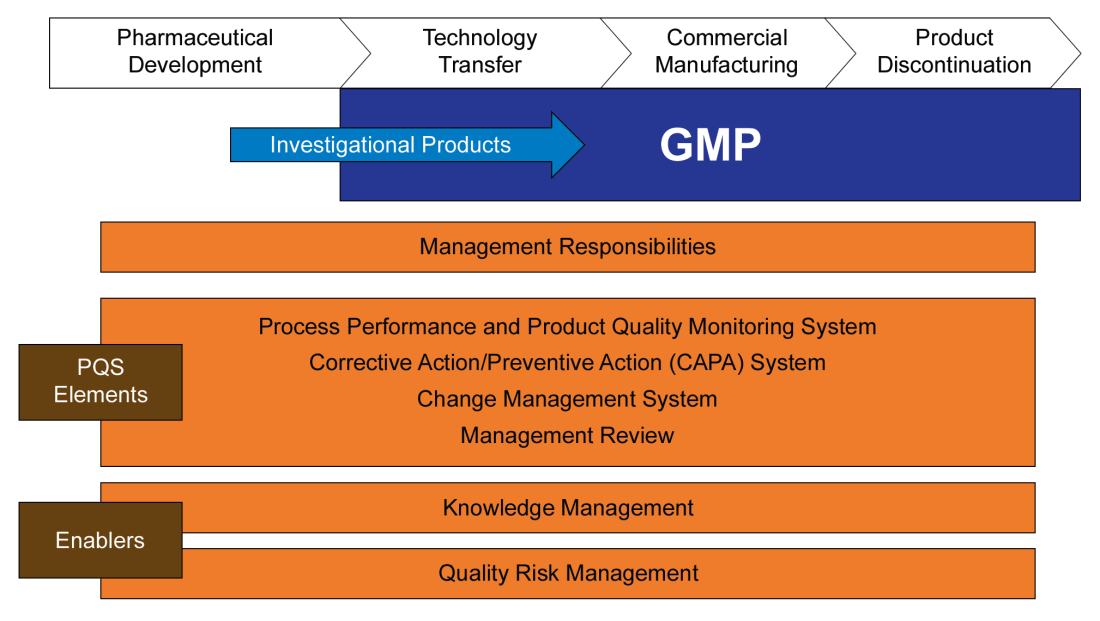

ICHQ10 “Pharmaceutical Quality System” was finalized in 2008 and adopted from 2008-2010 (except Canada). Q10 lays out a quality system approach that, based on a science and risk-based approach, establishes 4 pillars: Process Performance and Product Quality Monitoring; CAPA; Change Control; and, Management Review. Your welcome pharmaceutical industry, the ICH has now told you how to do your job and after Q10 we are getting serious about figuring out how to get ready for new technologies and be nimble and stuff.

The Pharmaceutical lifecycle is set out in 4 phases: Pharmaceutical Development, Technology Transfer, Commercial Manufacturing and Product Discontinuation; with the requirements of each pillar being explained at a high level for each phase.

Knowledge management gets poked at as a key enabler.

Q9 and Q10 together basically set out to demonstrate just how to do the things that are a requirement in order to have quality by design (Q8) but also show how to move from Q7 to a proactive, risk-based approach to running your pharmaceutical lifecycle. We are moving from a set of discrete compliance requirements (which Q7 is sort of a bow-tie around) to a comprehensive quality systems approach over the lifetime of the product to establish and maintain a state of control and facilitate continual improvement. Breaking down silos this approach united product development with manufacturing, with distribution. I feel almost like I am having a mystic experience when I contemplate what this path we are on can do. Because frankly, we are still on the path.

Q11

ICHQ11 “Development and Manufacture of Drug Substances” was finalized in 2012 and adopted in the next 4 years. This is a bow guidance as it shows how to implement Q8, with the support of Q9 and Q10. This is based on six principles that stem from the three previous guidances: Drug-substance quality linked to drug product; Process-development tools; Approaches to development; Drug-substance CQAs; Linking material attributes and process parameters to drug substance CQAs; and, Design space.

Q11 is our blueprint, drug substance manufacturers. Others can learn a lot of how to implement Q8-10 through reading, understanding and internalizing this document.

Q12

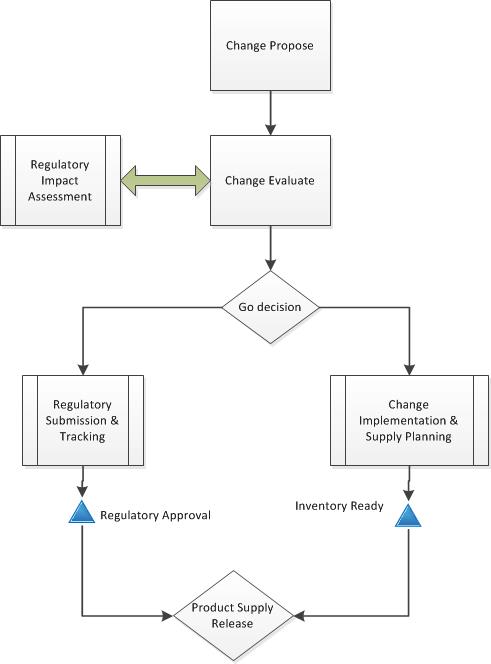

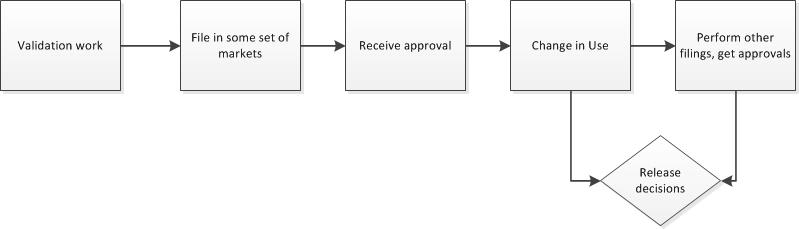

In November of 2017 the long-anticipated draft of ICHQ12 “Technical and Quality Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle management” was published. Q12 provides a framework to manage CMC changes across the lifecycle of the product. In short, it utilizes Q8, Q9, and Q10 and says if you do those things then here are how post-marketing changes will work and the expected regulatory benefits. Which means getting changes to market faster. Knowledge management is expanded upon as a concept.

Q12 enshrines established conditions, which is a term that wraps a few QbD concepts and provides a regulatory framework. Still, in draft, there is a fair share of controversy (for example, the EMA can’t adopt it as is it appears) and I am certainly curious to see what the final result is.

At this point we have: Q7 – summary of GMPs; Q8 – QbD; Q9- risk management; Q10 – quality systems; Q11 – a roadmap for drug substances; and in draft, Q12 – lifecycle management.

The ICH primary exists as a way for regulatory bodies to align and work out the thorny issues facing the industry. The process is not perfect, but it’s much better to be involved then to ignore.

Q13 and Q14

This last June the ICH met and, amongst other things, announced the roadmap for what is next:

- Analytical Procedure Development and Revision of Q2(R1) AnalyticalValidation (Q2(R2)/Q14)

- Continuous manufacturing (Q13)

Q2 is desperately in need of revision. It was finalized back in 1996 and does not take advantage of all the thought process expressed in Q8-Q11. Apply QbD, risk management, and quality systems will hopefully improve this guidance greatly.

Q13 appears to be another in the line of how to apply the Q8-Q10 concepts, this time to everyone’s favorite topics – continuous manufacturing. Both the FDA and EMA have been taking stabs at this concept, and I look forward to seeing the alignment and development through this process.

I look forward to seeing formal concept papers on both.