The draft revision of EU GMP Chapter 4 on Documentation represents more than just an update—it signals a paradigm shift toward digitalization, enhanced data integrity, and risk-based quality management in pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The Digital Transformation Imperative

The draft Chapter 4 emerges from a recognition that pharmaceutical manufacturing has fundamentally changed since 2011. The rise of Industry 4.0, artificial intelligence in manufacturing decisions, and the critical importance of data integrity following numerous regulatory actions have necessitated a complete reconceptualization of documentation requirements.

The new framework introduces comprehensive data governance systems, risk-based approaches throughout the documentation lifecycle, and explicit requirements for hybrid systems that combine paper and electronic elements. These changes reflect lessons learned from data integrity violations that have cost the industry billions in remediation and lost revenue.

Detailed Document Type Analysis

Master Documents: Foundation of Quality Systems

| Document Type | Current Chapter 4 (2011) Requirements | Draft Chapter 4 (2025) Requirements | FDA 21 CFR 211 | ICH Q7 | WHO GMP | ISO 13485 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site Master File | A document describing the GMP related activities of the manufacturer | Refer to EU GMP Guidelines, Volume 4 ‘Explanatory Notes on the preparation of a Site Master File’ | No specific equivalent, but facility information requirements under §211.176 | Section 2.5 – Documentation system should include site master file equivalent information | Section 4.1 – Site master file requirements similar to EU GMP | Quality manual requirements under Section 4.2.2 |

| Validation Master Plan | Not specified | A document describing the key elements of the site qualification and validation program | Process validation requirements under §211.100 and §211.110 | Section 12 – Validation requirements for critical operations | Section 4.2 – Validation and qualification programs | Validation planning under Section 7.5.6 and design validation |

The introduction of the Validation Master Plan as a mandatory master document represents the most significant addition to this category. This change acknowledges the critical role of systematic validation in modern pharmaceutical manufacturing and aligns EU GMP with global best practices seen in FDA and ICH frameworks.

The Site Master File requirement, while maintained, now references more detailed guidance, suggesting increased regulatory scrutiny of facility information and manufacturing capabilities.

Instructions: The Operational Backbone

| Document Type | Current Chapter 4 (2011) Requirements | Draft Chapter 4 (2025) Requirements | FDA 21 CFR 211 | ICH Q7 | WHO GMP | ISO 13485 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specifications | Describe in detail the requirements with which the products or materials used or obtained during manufacture have to conform. They serve as a basis for quality evaluation | Refer to glossary for definition | Component specifications §211.84, drug product specifications §211.160 | Section 7.3 – Specifications for starting materials, intermediates, and APIs | Section 4.12 – Specifications for starting materials and finished products | Requirements specifications under Section 7.2.1 |

| Manufacturing Formulae, Processing, Packaging and Testing Instructions | Provide detail all the starting materials, equipment and computerised systems (if any) to be used and specify all processing, packaging, sampling and testing instructions | Provide complete detail on all the starting materials, equipment, and computerised systems (if any) to be used and specify all processing, packaging, sampling, and testing instructions to ensure batch to batch consistency | Master production and control records §211.186, production record requirements §211.188 | Section 6.4 – Master production instructions and batch production records | Section 4.13 – Manufacturing formulae and processing instructions | Production and service provision instructions Section 7.5.1 |

| Procedures (SOPs) | Give directions for performing certain operations | Otherwise known as Standard Operating Procedures, documented set of instructions for performing and recording operations | Written procedures required throughout Part 211 for various operations | Section 6.1 – Written procedures for all critical operations | Section 4.14 – Standard operating procedures for all operations | Documented procedures throughout the standard, Section 4.2.1 |

| Technical/Quality Agreements | Are agreed between contract givers and acceptors for outsourced activities | Written proof of agreement between contract givers and acceptors for outsourced activities | Contract manufacturing requirements implied, vendor qualification | Section 16 – Contract manufacturers agreements and responsibilities | Section 7 – Contract manufacture and analysis agreements | Outsourcing agreements under Section 7.4 – Purchasing |

The enhancement of Manufacturing Instructions to explicitly require “batch to batch consistency” represents a crucial evolution. This change reflects increased regulatory focus on manufacturing reproducibility and aligns with FDA’s process validation lifecycle approach and ICH Q7’s emphasis on consistent API production.

Procedures (SOPs) now explicitly encompass both “performing and recording operations,” emphasizing the dual nature of documentation as both instruction and evidence creation1. This mirrors FDA 21 CFR 211’s comprehensive procedural requirements and ISO 13485’s systematic approach to documented procedures910.

The transformation of Technical Agreements into Technical/Quality Agreements with emphasis on “written proof” reflects lessons learned from outsourcing challenges and regulatory enforcement actions. This change aligns with ICH Q7’s detailed contract manufacturer requirements and strengthens oversight of critical outsourced activities.

Records and Reports: Evidence of Compliance

| Document Type | Current Chapter 4 (2011) Requirements | Draft Chapter 4 (2025) Requirements | FDA 21 CFR 211 | ICH Q7 | WHO GMP | ISO 13485 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Records | Provide evidence of various actions taken to demonstrate compliance with instructions, e.g. activities, events, investigations, and in the case of manufactured batches a history of each batch of product | Provide evidence of various actions taken to demonstrate compliance with instructions, e.g. activities, events, investigations, and in the case of manufactured batches a history of each batch of product, including its distribution. Records include the raw data which is used to generate other records | Comprehensive record requirements throughout Part 211, §211.180 general requirements | Section 6.5 – Batch production records and Section 6.6 – Laboratory control records | Section 4.16 – Records requirements for all GMP activities | Quality records requirements under Section 4.2.4 |

| Certificate of Analysis | Provide a summary of testing results on samples of products or materials together with the evaluation for compliance to a stated specification | Provide a summary of testing results on samples of products or materials together with the evaluation for compliance to a stated specification | Laboratory records and test results §211.194, certificate requirements | Section 11.15 – Certificate of analysis for APIs | Section 6.8 – Certificates of analysis requirements | Test records and certificates under Section 7.5.3 |

| Reports | Document the conduct of particular exercises, projects or investigations, together with results, conclusions and recommendations | Document the conduct of exercises, studies, assessments, projects or investigations, together with results, conclusions and recommendations | Investigation reports §211.192, validation reports | Section 15 – Complaints and recalls, investigation reports | Section 4.17 – Reports for deviations, investigations, and studies | Management review reports Section 5.6, validation reports |

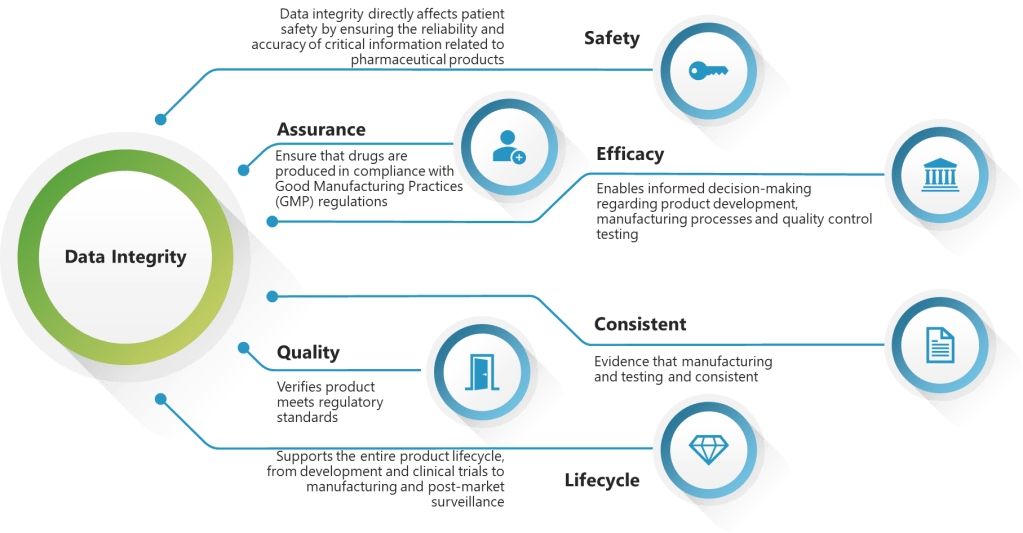

The expansion of Records to explicitly include “raw data” and “distribution information” represents perhaps the most impactful change for day-to-day operations. This enhancement directly addresses data integrity concerns highlighted by regulatory inspections and enforcement actions globally. The definition now states that “Records include the raw data which is used to generate other records,” establishing clear expectations for data traceability that align with FDA’s data integrity guidance and ICH Q7’s comprehensive record requirements.

Reports now encompass “exercises, studies, assessments, projects or investigations,” broadening the scope beyond the current “particular exercises, projects or investigations”. This expansion aligns with modern pharmaceutical operations that increasingly rely on various analytical studies and assessments for decision-making, matching ISO 13485’s comprehensive reporting requirements.

Revolutionary Framework Elements

Data Governance Revolution

The draft introduces an entirely new paradigm through its Data Governance Systems (Sections 4.10-4.18). This framework establishes:

- Complete lifecycle management from data creation through retirement

- Risk-based approaches considering data criticality and data risk

- Service provider oversight with periodic review requirements

- Ownership accountability throughout the data lifecycle

This comprehensive approach exceeds traditional GMP requirements and positions EU regulations at the forefront of data integrity management, surpassing even FDA’s current frameworks in systematic approach.

ALCOA++ Formalization

The draft formalizes ALCOA++ principles (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, Complete, Consistent, Enduring, Available, Traceable) with detailed definitions for each attribute. This represents a major comprehensive regulatory codification of these principles, providing unprecedented clarity for industry implementation.

ALCOA++ Principles: Comprehensive Data Integrity Framework

The Draft EU GMP Chapter 4 (2025) formalizes the ALCOA++ principles as the foundation for data integrity in pharmaceutical manufacturing. This represents the first comprehensive regulatory codification of these expanded data integrity principles, building upon the traditional ALCOA framework with five additional critical elements.

Complete ALCOA++ Requirements Table

| Principle | Core Requirement | Paper Implementation | Electronic Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A – Attributable | Identify who performed the task and when | Signatures, dates, initials | User authentication, e-signatures |

| L – Legible | Information must be readable and unambiguous | Clear writing, permanent ink | Proper formats, search functionality |

| C – Contemporaneous | Record actions as they happen in real-time | Immediate recording | System timestamps, workflow controls |

| O – Original | Preserve first capture of information | Original documents retained | Database integrity, backups |

| A – Accurate | Ensure truthful representation of facts | Training, calibrated equipment | System validation, automated checks |

| + Complete | Include all critical information and metadata | Complete data, no missing pages | Metadata capture, completeness checks |

| + Consistent | Standardize data creation and processing | Standard formats, consistent units | Data standards, validation rules |

| + Enduring | Maintain records throughout retention period | Archival materials, proper storage | Database integrity, migration plans |

| + Available | Ensure accessibility for authorized personnel | Organized filing, access controls | Role-based access, query capabilities |

| + Traceable | Enable tracing of data history and changes | Sequential numbering, change logs | Audit trails, version control |

Hybrid Systems Management

Recognizing the reality of modern pharmaceutical operations, the draft dedicates sections 4.82-4.85 to hybrid systems that combine paper and electronic elements. This practical approach acknowledges that many manufacturers operate in mixed environments and provides specific requirements for managing these complex systems.

A New Era of Pharmaceutical Documentation

The draft EU GMP Chapter 4 represents the most significant evolution in pharmaceutical documentation requirements in over a decade. By introducing comprehensive data governance frameworks, formalizing data integrity principles, and acknowledging the reality of digital transformation, these changes position European regulations as global leaders in modern pharmaceutical quality management.

For industry professionals, these changes offer both challenges and opportunities. Organizations that proactively embrace these new paradigms will not only achieve regulatory compliance but will also realize operational benefits through improved data quality, enhanced decision-making capabilities, and reduced compliance costs.

The evolution from simple documentation requirements to comprehensive data governance systems reflects the maturation of the pharmaceutical industry and its embrace of digital technologies. As we move toward implementation, the industry’s response to these changes will shape the future of pharmaceutical manufacturing for decades to come.

The message is clear: the future of pharmaceutical documentation is digital, risk-based, and comprehensive. Organizations that recognize this shift and act accordingly will thrive in the new regulatory environment, while those that cling to outdated approaches risk being left behind in an increasingly sophisticated and demanding regulatory landscape.