The pharmaceutical industry has operated for over a decade under the comfortable assumption that GAMP 5’s risk-based guidance for system requirements represented industry best practice—helpful, comprehensive, but ultimately voluntary. Section 6 of the draft Annex 11 moves many things from recommended to mandated. What GAMP 5 suggested as scalable guidance, Annex 11 codifies as enforceable regulation. For computer system validation professionals, this isn’t just an update—it’s a fundamental shift from “how we should do it” to “how we must do it.”

This transformation carries profound implications that extend far beyond documentation requirements. Section 6 represents the regulatory codification of modern system engineering practices, forcing organizations to abandon the shortcuts, compromises, and “good enough” approaches that have persisted despite GAMP 5’s guidance. More significantly, it establishes system requirements as the immutable foundation of validation rather than merely an input to the process.

For CSV experts who have spent years evangelizing GAMP 5 principles within organizations that treated requirements as optional documentation, Section 6 provides regulatory teeth that will finally compel comprehensive implementation. However, it also raises the stakes dramatically—what was once best practice guidance subject to interpretation becomes regulatory obligation subject to inspection.

The Mandatory Transformation: From Guidance to Regulation

6.1: GMP Functionality—The End of Requirements Optionality

The opening requirement of Section 6 eliminates any ambiguity about system requirements documentation: “A regulated user should establish and approve a set of system requirements (e.g. a User Requirements Specification, URS), which accurately describe the functionality the regulated user has automated and is relying on when performing GMP activities.”

This language transforms what GAMP 5 positioned as risk-based guidance into regulatory mandate. The phrase “should establish and approve” in regulatory context carries the force of “must“—there is no longer discretion about whether to document system requirements. Every computerized system touching GMP activities requires formal requirements documentation, regardless of system complexity, development approach, or organizational preference.

The scope is deliberately comprehensive, explicitly covering “whether a system is developed in-house, is a commercial off-the-shelf product, or is provided as-a-service” and “independently on whether it is developed following a linear or iterative software development process.” This eliminates common industry escapes: cloud services can’t claim exemption because they’re external; agile development can’t avoid documentation because it’s iterative; COTS systems can’t rely solely on vendor documentation because they’re pre-built.

The requirement for accuracy in describing “functionality the regulated user has automated and is relying on” establishes a direct link between system capabilities and GMP dependencies. Organizations must explicitly identify and document what GMP activities depend on system functionality, creating traceability between business processes and technical capabilities that many current validation approaches lack.

Major Strike Against the Concept of “Indirect”

The new draft Annex 11 explicitly broadens the scope of requirements for user requirements specifications (URS) and validation to cover all computerized systems with GMP relevance—not just those with direct product or decision-making impact, but also indirect GMP systems. This means systems that play a supporting or enabling role in GMP activities (such as underlying IT infrastructure, databases, cloud services, SaaS platforms, integrated interfaces, and any outsourced or vendor-managed digital environments) are fully in scope.

Section 6 of the draft states that user requirements must “accurately describe the functionality the regulated user has automated and is relying on when performing GMP activities,” with no exemption or narrower definition for indirect systems. It emphasizes that this principle applies “regardless of whether a system is developed in-house, is a commercial off-the-shelf product, or is provided as-a-service, and independently of whether it is developed following a linear or iterative software development process.” The regulated user is responsible for approving, controlling, and maintaining these requirements over the system’s lifecycle—even if the system is managed by a third party or only indirectly involved in GMP data or decision workflows.

Importantly, the language and supporting commentaries make it clear that traceability of user requirements throughout the lifecycle is mandatory for all systems with GMP impact—direct or indirect. There is no explicit exemption in the draft for indirect GMP systems. Regulatory and industry analyses confirm that the burden of documented, risk-assessed, and lifecycle-maintained user requirements sits equally with indirect systems as with direct ones, as long as they play a role in assuring product quality, patient safety, or data integrity.

In practice, this means organizations must extend their URS, specification, and validation controls to any computerized system that through integration, support, or data processing could influence GMP compliance. The regulated company remains responsible for oversight, traceability, and quality management of those systems, whether or not they are operated by a vendor or IT provider. This is a significant expansion from previous regulatory expectations and must be factored into computerized system inventories, risk assessments, and validation strategies going forward.

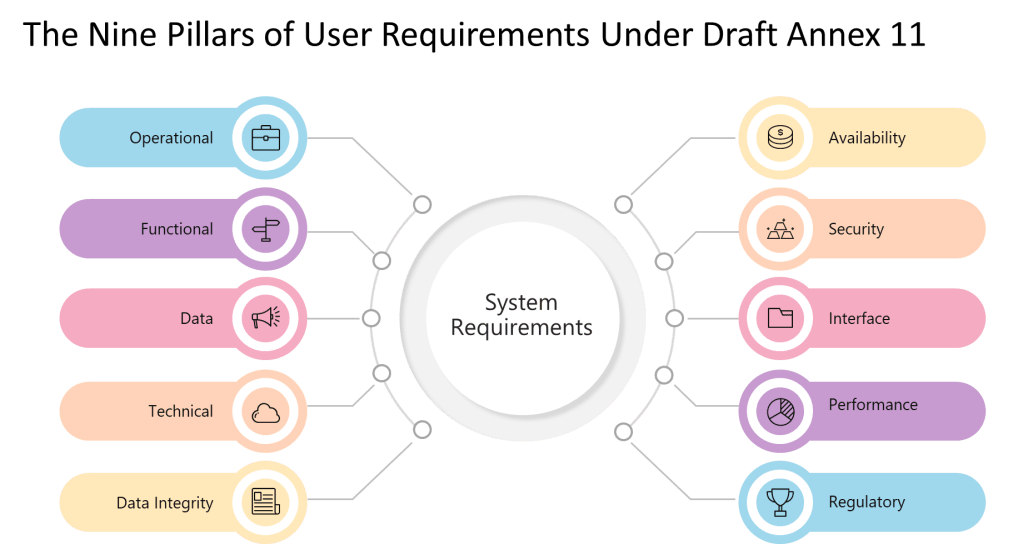

9 Pillars of a User Requirements

| Pillar | Description | Practical Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Operational | Requirements describing how users will operate the system for GMP tasks. | Workflow steps, user roles, batch record creation. |

| Functional | Features and functions the system must perform to support GMP processes. | Electronic signatures, calculation logic, alarm triggers. |

| Data Integrity | Controls to ensure data is complete, consistent, correct, and secure. | Audit trails, ALCOA+ requirements, data record locking. |

| Technical | Technical characteristics or constraints of the system. | Platform compatibility, failover/recovery, scalability. |

| Interface | How the system interacts with other systems, hardware, or users. | Equipment integration, API requirements, data lakes |

| Performance | Speed, capacity, or throughput relevant to GMP operations. | Batch processing times, max concurrent users, volume limits. |

| Availability | System uptime, backup, and disaster recovery necessary for GMP. | 99.9% uptime, scheduled downtime windows, backup frequency. |

| Security | How access is controlled and how data is protected against threats. | Password policy, MFA, role-based access, encryption. |

| Regulatory | Explicit requirements imposed by GMP regulations and standards. | Part 11/Annex 11 compliance, data retention, auditability. |

6.2: Extent and Detail—Risk-Based Rigor, Not Risk-Based Avoidance

Section 6.2 appears to maintain GAMP 5’s risk-based philosophy by requiring that “extent and detail of defined requirements should be commensurate with the risk, complexity and novelty of a system.” However, the subsequent specifications reveal a much more prescriptive approach than traditional risk-based frameworks.

The requirement that descriptions be “sufficient to support subsequent risk analysis, specification, design, purchase, configuration, qualification and validation” establishes requirements documentation as the foundation for the entire system lifecycle. This moves beyond GAMP 5’s emphasis on requirements as input to validation toward positioning requirements as the definitive specification against which all downstream activities are measured.

The explicit enumeration of requirement types—”operational, functional, data integrity, technical, interface, performance, availability, security, and regulatory requirements”—represents a significant departure from GAMP 5’s more flexible categorization. Where GAMP 5 allows organizations to define requirement categories based on system characteristics and business needs, Annex 11 mandates coverage of nine specific areas regardless of system type or risk level.

This prescriptive approach reflects regulatory recognition that organizations have historically used “risk-based” as justification for inadequate requirements documentation. By specifying minimum coverage areas, Section 6 establishes a floor below which requirements documentation cannot fall, regardless of risk assessment outcomes.

The inclusion of “process maps and data flow diagrams” as recommended content acknowledges the reality that modern pharmaceutical operations involve complex, interconnected systems where understanding data flows and process dependencies is essential for effective validation. This requirement will force organizations to develop system-level understanding rather than treating validation as isolated technical testing.

6.3: Ownership—User Accountability in the Cloud Era

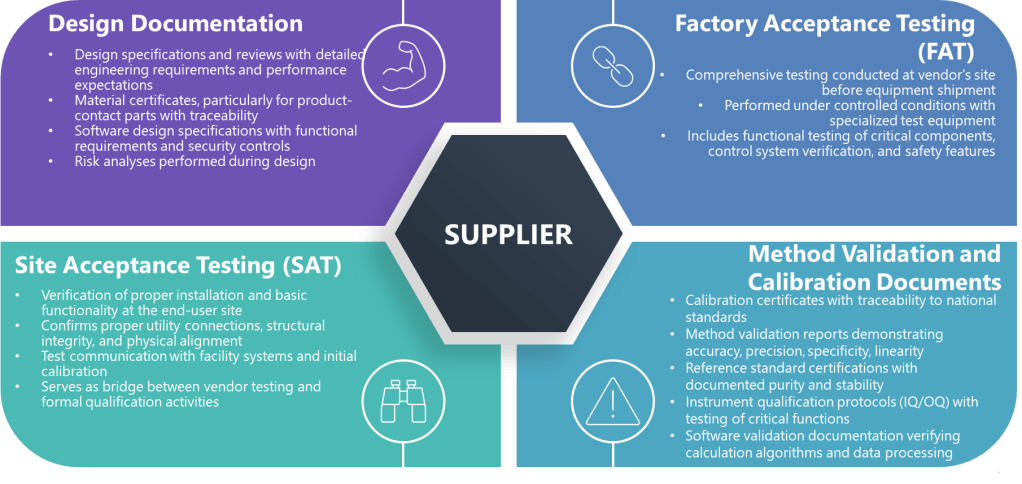

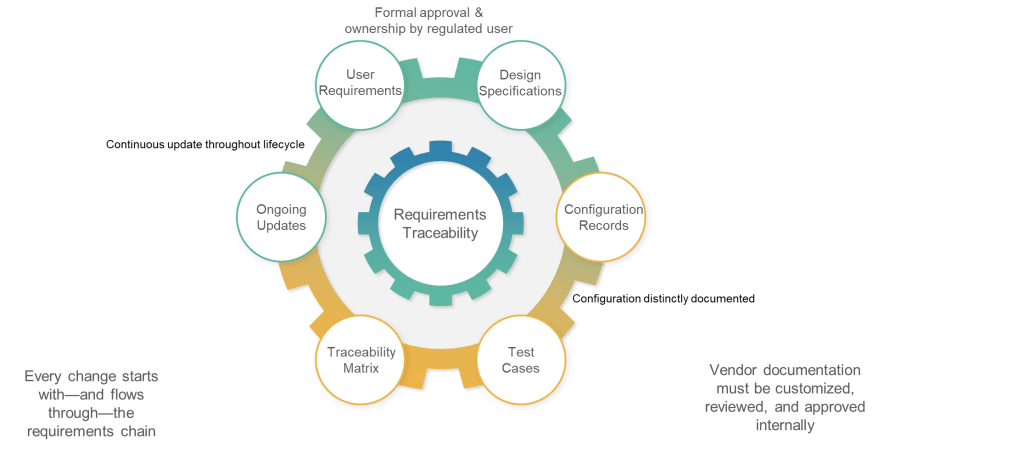

Perhaps the most significant departure from traditional industry practice, Section 6.3 addresses the growing trend toward cloud services and vendor-supplied systems by establishing unambiguous user accountability for requirements documentation. The requirement that “the regulated user should take ownership of the document covering the implemented version of the system and formally approve and control it” eliminates common practices where organizations rely entirely on vendor-provided documentation.

This requirement acknowledges that vendor-supplied requirements specifications rarely align perfectly with specific organizational needs, GMP processes, or regulatory expectations. While vendors may provide generic requirements documentation suitable for broad market applications, pharmaceutical organizations must customize, supplement, and formally adopt these requirements to reflect their specific implementation and GMP dependencies.

The language “carefully review and approve the document and consider whether the system fulfils GMP requirements and company processes as is, or whether it should be configured or customised” requires active evaluation rather than passive acceptance. Organizations cannot simply accept vendor documentation as sufficient—they must demonstrate that they have evaluated system capabilities against their specific GMP needs and either confirmed alignment or documented necessary modifications.

This ownership requirement will prove challenging for organizations using large cloud platforms or SaaS solutions where vendors resist customization of standard documentation. However, the regulatory expectation is clear: pharmaceutical companies cannot outsource responsibility for demonstrating that system capabilities meet their specific GMP requirements.

6.4: Update—Living Documentation, Not Static Archives

Section 6.4 addresses one of the most persistent failures in current validation practice: requirements documentation that becomes obsolete immediately after initial validation. The requirement that “requirements should be updated and maintained throughout the lifecycle of a system” and that “updated requirements should form the very basis for qualification and validation” establishes requirements as living documentation rather than historical artifacts.

This approach reflects the reality that modern computerized systems undergo continuous change through software updates, configuration modifications, hardware refreshes, and process improvements. Traditional validation approaches that treat requirements as fixed specifications become increasingly disconnected from operational reality as systems evolve.

The phrase “form the very basis for qualification and validation” positions requirements documentation as the definitive specification against which system performance is measured throughout the lifecycle. This means that any system change must be evaluated against current requirements, and any requirements change must trigger appropriate validation activities.

This requirement will force organizations to establish requirements management processes that rival those used in traditional software development organizations. Requirements changes must be controlled, evaluated for impact, and reflected in validation documentation—capabilities that many pharmaceutical organizations currently lack.

6.5: Traceability—Engineering Discipline for Validation

The traceability requirement in Section 6.5 codifies what GAMP 5 has long recommended: “Documented traceability between individual requirements, underlaying design specifications and corresponding qualification and validation test cases should be established and maintained.” However, the regulatory context transforms this from validation best practice to compliance obligation.

The emphasis on “effective tools to capture and hold requirements and facilitate the traceability” acknowledges that manual traceability management becomes impractical for complex systems with hundreds or thousands of requirements. This requirement will drive adoption of requirements management tools and validation platforms that can maintain automated traceability throughout the system lifecycle.

Traceability serves multiple purposes in the validation context: ensuring comprehensive test coverage, supporting impact assessment for changes, and providing evidence of validation completeness. Section 6 positions traceability as fundamental validation infrastructure rather than optional documentation enhancement.

For organizations accustomed to simplified validation approaches where test cases are developed independently of detailed requirements, this traceability requirement represents a significant process change requiring tool investment and training.

6.6: Configuration—Separating Standard from Custom

The final subsection addresses configuration management by requiring clear documentation of “what functionality, if any, is modified or added by configuration of a system.” This requirement recognizes that most modern pharmaceutical systems involve significant configuration rather than custom development, and that configuration decisions have direct impact on validation scope and approaches.

The distinction between standard system functionality and configured functionality is crucial for validation planning. Standard functionality may be covered by vendor testing and certification, while configured functionality requires user validation. Section 6 requires this distinction to be explicit and documented.

The requirement for “controlled configuration specification” separate from requirements documentation reflects recognition that configuration details require different management approaches than functional requirements. Configuration specifications must reflect the actual system implementation rather than desired capabilities.

Comparison with GAMP 5: Evolution Becomes Revolution

Philosophical Alignment with Practical Divergence

Section 6 maintains GAMP 5’s fundamental philosophy—risk-based validation supported by comprehensive requirements documentation—while dramatically changing implementation expectations. Both frameworks emphasize user ownership of requirements, lifecycle management, and traceability as essential validation elements. However, the regulatory context of Annex 11 transforms voluntary guidance into enforceable obligation.

GAMP 5’s flexibility in requirements categorization and documentation approaches reflects its role as guidance suitable for diverse organizational contexts and system types. Section 6’s prescriptive approach reflects regulatory recognition that flexibility has often been interpreted as optionality, leading to inadequate requirements documentation that fails to support effective validation.

The risk-based approach remains central to both frameworks, but Section 6 establishes minimum standards that apply regardless of risk assessment outcomes. While GAMP 5 might suggest that low-risk systems require minimal requirements documentation, Section 6 mandates coverage of nine requirement areas for all GMP systems.

Documentation Structure and Content

GAMP 5’s traditional document hierarchy—URS, Functional Specification, Design Specification—becomes more fluid under Section 6, which focuses on ensuring comprehensive coverage rather than prescribing specific document structures. This reflects recognition that modern development approaches, including agile and DevOps practices, may not align with traditional waterfall documentation models.

However, Section 6’s explicit enumeration of requirement types provides more prescriptive guidance than GAMP 5’s flexible approach. Where GAMP 5 might allow organizations to define requirement categories based on system characteristics, Section 6 mandates coverage of operational, functional, data integrity, technical, interface, performance, availability, security, and regulatory requirements.

The emphasis on process maps, data flow diagrams, and use cases reflects modern system complexity where understanding interactions and dependencies is essential for effective validation. GAMP 5 recommends these approaches for complex systems; Section 6 suggests their use “where relevant” for all systems.

Vendor and Service Provider Management

Both frameworks emphasize user responsibility for requirements even when vendors provide initial documentation. However, Section 6 uses stronger language about user ownership and control, reflecting increased regulatory concern about organizations that delegate requirements definition to vendors without adequate oversight.

GAMP 5’s guidance on supplier assessment and leveraging vendor documentation remains relevant under Section 6, but the regulatory requirement for user ownership and approval creates higher barriers for simply accepting vendor-provided documentation as sufficient.

Implementation Challenges for CSV Professionals

Organizational Capability Development

Most pharmaceutical organizations will require significant capability development to meet Section 6 requirements effectively. Traditional validation teams focused on testing and documentation must develop requirements engineering capabilities comparable to those found in software development organizations.

This transformation requires investment in requirements management tools, training for validation professionals, and establishment of requirements governance processes. Organizations must develop capabilities for requirements elicitation, analysis, specification, validation, and change management throughout the system lifecycle.

The traceability requirement particularly challenges organizations accustomed to informal relationships between requirements and test cases. Automated traceability management requires tool investments and process changes that many validation teams are unprepared to implement.

Integration with Existing Validation Approaches

Section 6 requirements must be integrated with existing validation methodologies and documentation structures. Organizations following traditional IQ/OQ/PQ approaches must ensure that requirements documentation supports and guides qualification activities rather than existing as parallel documentation.

The requirement for requirements to “form the very basis for qualification and validation” means that test cases must be explicitly derived from and traceable to documented requirements. This may require significant changes to existing qualification protocols and test scripts.

Organizations using risk-based validation approaches aligned with GAMP 5 guidance will find philosophical alignment with Section 6 but must adapt to more prescriptive requirements for documentation content and structure.

Technology and Tool Requirements

Effective implementation of Section 6 requirements typically requires requirements management tools capable of supporting specification, traceability, change control, and lifecycle management. Many pharmaceutical validation teams currently lack access to such tools or experience in their use.

Tool selection must consider integration with existing validation platforms, support for regulated environments, and capabilities for automated traceability maintenance. Organizations may need to invest in new validation platforms or significantly upgrade existing capabilities.

The emphasis on maintaining requirements throughout the system lifecycle requires tools that support ongoing requirements management rather than just initial documentation. This may conflict with validation approaches that treat requirements as static inputs to qualification activities.

Strategic Implications for the Industry

Convergence of Software Engineering and Pharmaceutical Validation

Section 6 represents convergence between pharmaceutical validation practices and mainstream software engineering approaches. Requirements engineering, long established in software development, becomes mandatory for pharmaceutical computerized systems regardless of development approach or vendor involvement.

This convergence benefits the industry by leveraging proven practices from software engineering while maintaining the rigor and documentation requirements essential for regulated environments. However, it requires pharmaceutical organizations to develop capabilities traditionally associated with software development rather than manufacturing and quality assurance.

The result should be more robust validation practices better aligned with modern system development approaches and capable of supporting the complex, interconnected systems that characterize contemporary pharmaceutical operations.

Vendor Relationship Evolution

Section 6 requirements will reshape relationships between pharmaceutical companies and system vendors. The requirement for user ownership of requirements documentation means that vendors must support more sophisticated requirements management processes rather than simply providing generic specifications.

Vendors that can demonstrate alignment with Section 6 requirements through comprehensive documentation, traceability tools, and support for user customization will gain competitive advantages. Those that resist pharmaceutical-specific requirements management approaches may find their market opportunities limited.

The emphasis on configuration management will drive vendors to provide clearer distinctions between standard functionality and customer-specific configurations, supporting more effective validation planning and execution.

The Regulatory Codification of Modern Validation

Section 6 of the draft Annex 11 represents the regulatory codification of modern computerized system validation practices. What GAMP 5 recommended through guidance, Annex 11 mandates through regulation. What was optional becomes obligatory; what was flexible becomes prescriptive; what was best practice becomes compliance requirement.

For CSV professionals, Section 6 provides regulatory support for comprehensive validation approaches while raising the stakes for inadequate implementation. Organizations that have struggled to implement effective requirements management now face regulatory obligation rather than just professional guidance.

The transformation from guidance to regulation eliminates organizational discretion about requirements documentation quality and comprehensiveness. While risk-based approaches remain valid for scaling validation effort, minimum standards now apply regardless of risk assessment outcomes.

Success under Section 6 requires pharmaceutical organizations to embrace software engineering practices for requirements management while maintaining the documentation rigor and process control essential for regulated environments. This convergence benefits the industry by improving validation effectiveness while ensuring compliance with evolving regulatory expectations.

The industry faces a choice: proactively develop capabilities to meet Section 6 requirements or reactively respond to inspection findings and enforcement actions. For organizations serious about digital transformation and validation excellence, Section 6 provides a roadmap for regulatory-compliant modernization of validation practices.

| Requirement Area | Draft Annex 11 Section 6 | GAMP 5 Requirements | Key Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Requirements Documentation | Mandatory – Must establish and approve system requirements (URS) | Recommended – URS should be developed based on system category and complexity | Organizations must document requirements for ALL GMP systems, regardless of size or complexity |

| Risk-Based Approach | Extent and detail must be commensurate with risk, complexity, and novelty | Risk-based approach fundamental – validation effort scaled to risk | Risk assessment determines documentation detail but cannot eliminate requirement categories |

| Functional Requirements | Must include 9 specific requirement types: operational, functional, data integrity, technical, interface, performance, availability, security, regulatory | Functional requirements should be SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Testable) | All 9 areas must be addressed; risk determines depth, not coverage |

| Traceability Requirements | Documented traceability between requirements, design specs, and test cases required | Traceability matrix recommended – requirements linked through design to testing | Requires investment in traceability tools and processes for complex systems |

| Requirement Ownership | Regulated user must take ownership even if vendor provides initial requirements | User ownership emphasized, even for purchased systems | Cannot simply accept vendor documentation; must customize and formally approve |

| Lifecycle Management | Requirements must be updated and maintained throughout system lifecycle | Requirements managed through change control throughout lifecycle | Requires ongoing requirements management process, not just initial documentation |

| Configuration Management | Configuration options must be described in requirements; chosen configuration documented in controlled spec | Configuration specifications separate from URS | Must clearly distinguish between standard functionality and configured features |

| Vendor-Supplied Requirements | Vendor requirements must be reviewed, approved, and owned by regulated user | Supplier assessment required – leverage supplier documentation where appropriate | Higher burden on users to customize vendor documentation for specific GMP needs |

| Validation Basis | Updated requirements must form basis for system qualification and validation | Requirements drive validation strategy and testing scope | Requirements become definitive specification against which system performance is measured |