The FDA’s April 30, 2025 warning letter to Rechon Life Science AB serves as a great learning opportunity about the importance robust investigation systems to contamination control to drive meaningful improvements. This Swedish contract manufacturer’s experience offers profound lessons for quality professionals navigating the intersection of EU Annex 1‘s contamination control strategy requirements and increasingly regulatory expectations. It is a mistake to think that just because the FDA doesn’t embrace the prescriptive nature of Annex 1 the agency is not fully aligned with the intent.

This Warning Letter resonates with similar systemic failures at companies like LeMaitre Vascular, Sanofi and others. The Rechon warning letter demonstrates a troubling but instructive pattern: organizations that fail to conduct meaningful contamination investigations inevitably find themselves facing regulatory action that could have been prevented through better investigation practices and systematic contamination control approaches.

The Cascade of Investigation Failures: Rechon’s Contamination Control Breakdown

Aseptic Process Failures and the Investigation Gap

Rechon’s primary violation centered on a fundamental breakdown in aseptic processing—operators were routinely touching critical product contact surfaces with gloved hands, a practice that was not only observed but explicitly permitted in their standard operating procedures. This represents more than poor technique; it reveals an organization that had normalized contamination risks through inadequate investigation and assessment processes.

The FDA’s citation noted that Rechon failed to provide environmental monitoring trend data for surface swab samples, representing exactly the kind of “aspirational data” problem. When investigation systems don’t capture representative information about actual manufacturing conditions, organizations operate in a state of regulatory blindness, making decisions based on incomplete or misleading data.

This pattern reflects a broader failure in contamination investigation methodology: environmental monitoring excursions require systematic evaluation that includes all environmental data (i.e. viable and non-viable tests) and must include areas that are physically adjacent or where related activities are performed. Rechon’s investigation gaps suggest they lacked these fundamental systematic approaches.

Environmental Monitoring Investigations: When Trend Analysis Fails

Perhaps more concerning was Rechon’s approach to persistent contamination with objectionable microorganisms—gram-negative organisms and spore formers—in ISO 5 and 7 areas since 2022. Their investigation into eight occurrences of gram-negative organisms concluded that the root cause was “operators talking in ISO 7 areas and an increase of staff illness,” a conclusion that demonstrates fundamental misunderstanding of contamination investigation principles.

As an aside, ISO7/Grade C is not normally an area we see face masks.

Effective investigations must provide comprehensive evaluation including:

- Background and chronology of events with detailed timeline analysis

- Investigation and data gathering activities including interviews and training record reviews

- SME assessments from qualified microbiology and manufacturing science experts

- Historical data review and trend analysis encompassing the full investigation zone

- Manufacturing process assessment to determine potential contributing factors

- Environmental conditions evaluation including HVAC, maintenance, and cleaning activities

Rechon’s investigation lacked virtually all of these elements, focusing instead on convenient behavioral explanations that avoided addressing systematic contamination sources. The persistence of gram-negative organisms and spore formers over a three-year period represented a clear adverse trend requiring a comprehensive investigation approach.

The Annex 1 Contamination Control Strategy Imperative: Beyond Compliance to Integration

The Paradigm Shift in Contamination Control

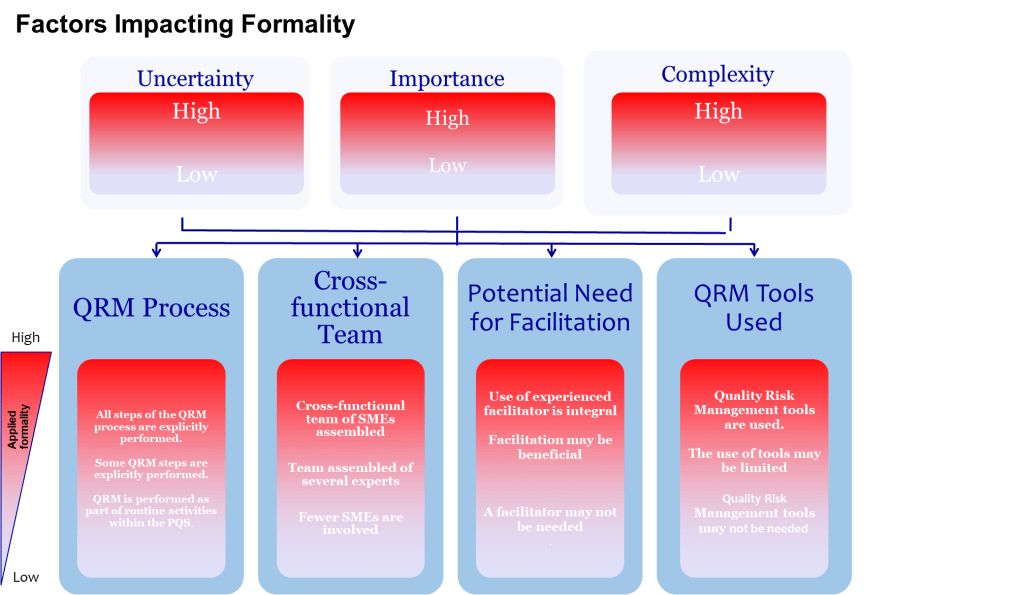

The revised EU Annex 1, effective since August 2023 demonstrates the current status of regulatory expectations around contamination control, moving from isolated compliance activities toward integrated risk management systems. The mandatory Contamination Control Strategy (CCS) requires manufacturers to develop comprehensive, living documents that integrate all aspects of contamination risk identification, mitigation, and monitoring.

Industry implementation experience since 2023 has revealed that many organizations are faiing to make meaningful connections between existing quality systems and the Annex 1 CCS requirements. Organizations struggle with the time and resource requirements needed to map existing contamination controls into coherent strategies, which often leads to discovering significant gaps in their understanding of their own processes.

Representative Environmental Monitoring Under Annex 1

The updated guidelines place emphasis on continuous monitoring and representative sampling that reflects actual production conditions rather than idealized scenarios. Rechon’s failure to provide comprehensive trend data demonstrates exactly the kind of gap that Annex 1 was designed to address.

Environmental monitoring must function as part of an integrated knowledge system that combines explicit knowledge (documented monitoring data, facility design specifications, cleaning validation reports) with tacit knowledge about facility-specific contamination risks and operational nuances. This integration demands investigation systems capable of revealing actual contamination patterns rather than providing comfortable explanations for uncomfortable realities.

The Design-First Philosophy

One of Annex 1’s most significant philosophical shifts is the emphasis on design-based contamination control rather than monitoring-based approaches. As we see from Warning Letters, and other regulatory intelligence, design gaps are frequently being cited as primary compliance failures, reinforcing the principle that organizations cannot monitor or control their way out of poor design.

This design-first philosophy fundamentally changes how contamination investigations must be conducted. Instead of simply investigating excursions after they occur, robust investigation systems must evaluate whether facility and process designs create inherent contamination risks that make excursions inevitable. Rechon’s persistent contamination issues suggest their investigation systems never addressed these fundamental design questions.

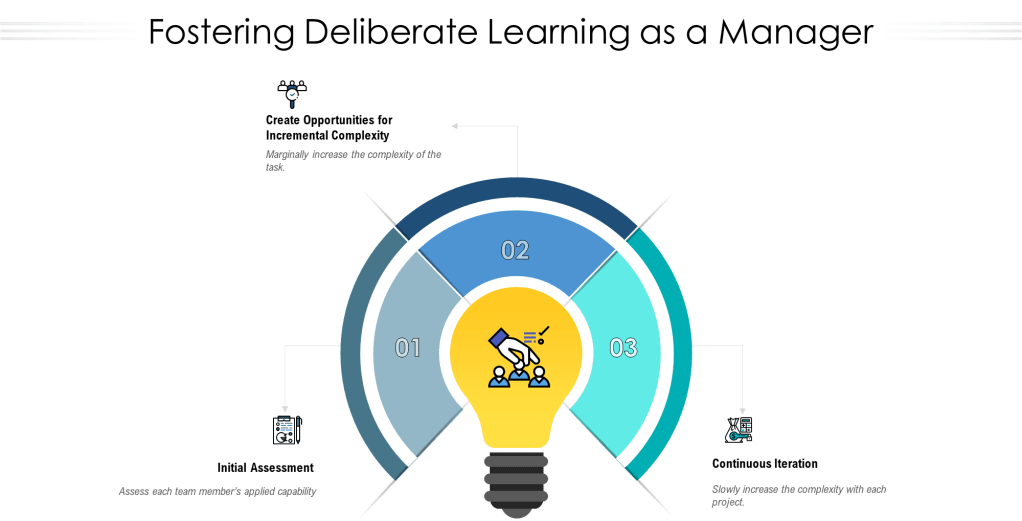

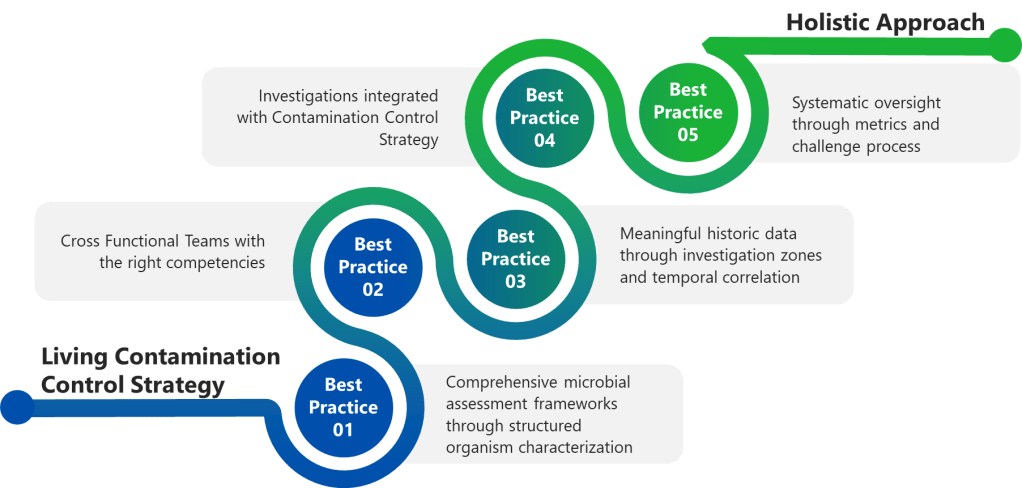

Best Practice 1: Implement Comprehensive Microbial Assessment Frameworks

Structured Organism Characterization

Effective contamination investigations begin with proper microbial assessments that characterize organisms based on actual risk profiles rather than convenient categorizations.

- Complete microorganism documentation encompassing organism type, Gram stain characteristics, potential sources, spore-forming capability, and objectionable organism status. The structured approach outlined in formal assessment templates ensures consistent evaluation across different sample types (in-process, environmental monitoring, water and critical utilities).

- Quantitative occurrence assessment using standardized vulnerability scoring systems that combine occurrence levels (Low, Medium, High) with nature and history evaluations. This matrix approach prevents investigators from minimizing serious contamination events through subjective assessments.

- Severity evaluation based on actual manufacturing impact rather than theoretical scenarios. For environmental monitoring excursions, severity assessments must consider whether microorganisms were detected in controlled environments during actual production activities, the potential for product contamination, and the effectiveness of downstream processing steps.

- Risk determination through systematic integration of vulnerability scores and severity ratings, providing objective classification of contamination risks that drives appropriate corrective action responses.

Rechon’s superficial investigation approach suggests they lacked these systematic assessment frameworks, focusing instead on behavioral explanations that avoided comprehensive organism characterization and risk assessment.

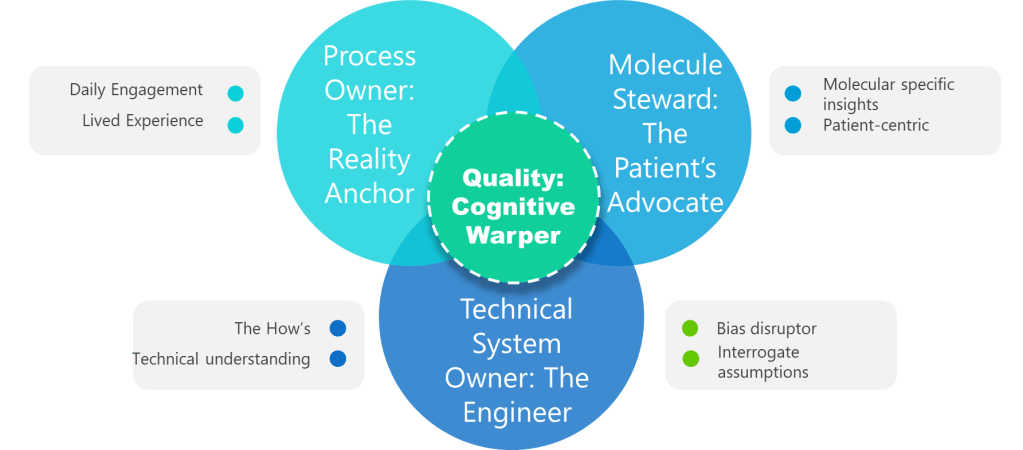

Best Practice 2: Establish Cross-Functional Investigation Teams with Defined Competencies

Investigation Team Composition and Qualifications

Major contamination investigations require dedicated cross-functional teams with clearly defined responsibilities and demonstrated competencies. The investigation lead must possess not only appropriate training and experience but also technical knowledge of the process and cGMP/quality system requirements, and ability to apply problem-solving tools.

Minimum team composition requirements for major investigations must include:

- Impacted Department representatives (Manufacturing, Facilities) with direct operational knowledge

- Subject Matter Experts (Manufacturing Sciences and Technology, QC Microbiology) with specialized technical expertise

- Contamination Control specialists serving as Quality Assurance approvers with regulatory and risk assessment expertise

Investigation scope requirements must encompass systematic evaluation including background/chronology documentation, comprehensive data gathering activities (interviews, training record reviews), SME assessments, impact statement development, historical data review and trend analysis, and laboratory investigation summaries.

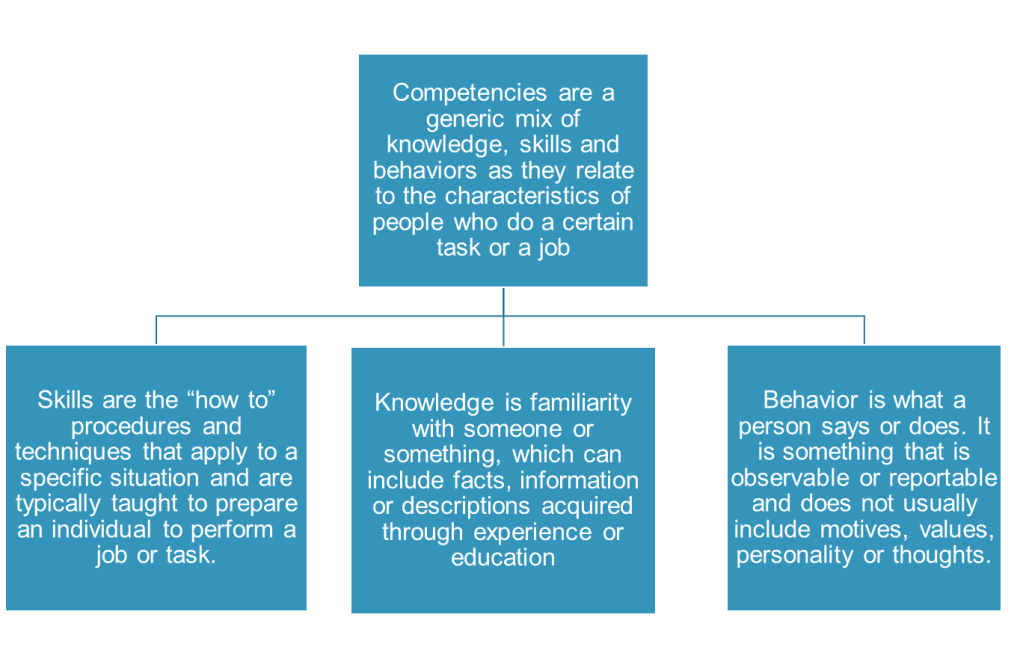

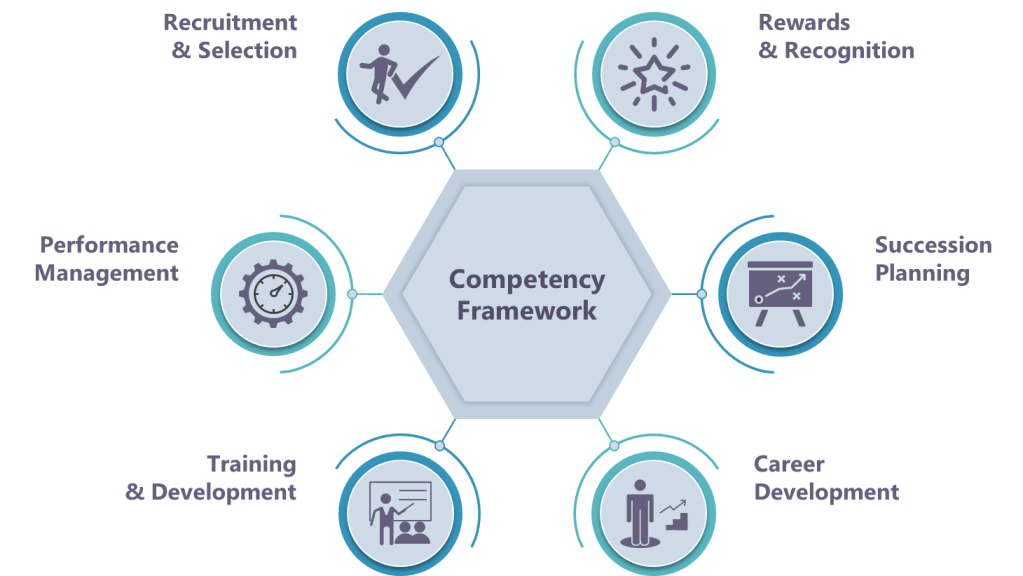

Training and Competency Management

Investigation team effectiveness depends on systematic competency development and maintenance. Teams must demonstrate proficiency in:

- Root cause analysis methodologies including fishbone analysis, why-why questioning, fault tree analysis, and failure mode and effects analysis approaches suited to contamination investigation contexts.

- Contamination microbiology principles including organism identification, source determination, growth condition assessment, and disinfectant efficacy evaluation specific to pharmaceutical manufacturing environments.

- Risk assessment and impact evaluation capabilities that can translate investigation findings into meaningful product, process, and equipment risk determinations.

- Regulatory requirement understanding encompassing both domestic and international contamination control expectations, investigation documentation standards, and CAPA development requirements.

The superficial nature of Rechon’s gram-negative organism investigation suggests their teams lacked these fundamental competencies, resulting in conclusions that satisfied neither regulatory expectations nor contamination control best practices.

Best Practice 3: Conduct Meaningful Historical Data Review and Comprehensive Trend Analysis

Investigation Zone Definition and Data Integration

Effective contamination investigations require comprehensive trend analysis that extends beyond simple excursion counting to encompass systematic pattern identification across related operational areas. As established in detailed investigation procedures, historical data review must include:

- Physically adjacent areas and related activities recognition that contamination events rarely occur in isolation. Processing activities spanning multiple rooms, secondary gowning areas leading to processing zones, material transfer airlocks, and all critical utility distribution points must be included in investigation zones.

- Comprehensive environmental data analysis encompassing all environmental data (i.e. viable and non-viable tests) to identify potential correlations between different contamination indicators that might not be apparent when examining single test types in isolation.

- Extended historical review capabilities for situations where limited or no routine monitoring was performed during the questioned time frame, requiring investigation teams to expand their analytical scope to capture relevant contamination patterns.

- Microorganism identification pattern assessment to determine shifts in routine microflora or atypical or objectionable organisms, enabling detection of contamination source changes that might indicate facility or process deterioration.

Temporal Correlation Analysis

Sophisticated trend analysis must correlate contamination events with operational activities, environmental conditions, and facility modifications that might contribute to adverse trends:

- Manufacturing activity correlation examining whether contamination patterns correlate with specific production campaigns, personnel schedules, cleaning activities, or maintenance operations that might introduce contamination sources.

- Environmental condition assessment including HVAC system performance, pressure differential maintenance, temperature and humidity control, and compressed air quality that could influence contamination recovery patterns.

- Facility modification impact evaluation determining whether physical environment changes, equipment installations, utility upgrades, or process modifications correlate with contamination trend emergence or intensification.

Rechon’s three-year history of gram-negative and spore-former recovery represented exactly the kind of adverse trend requiring this comprehensive analytical approach. Their failure to conduct meaningful trend analysis prevented identification of systematic contamination sources that behavioral explanations could never address.

Best Practice 4: Integrate Investigation Findings with Dynamic Contamination Control Strategy

Knowledge Management and CCS Integration

Under Annex 1 requirements, investigation findings must feed directly into the overall Contamination Control Strategy, creating continuous improvement cycles that enhance contamination risk understanding and control effectiveness. This integration requires sophisticated knowledge management systems that capture both explicit investigation data and tacit operational insights.

- Explicit knowledge integration encompasses formal investigation reports, corrective action documentation, trending analysis results, and regulatory correspondence that must be systematically incorporated into CCS risk assessments and control measure evaluations.

- Tacit knowledge capture including personnel experiences with contamination events, operational observations about facility or process vulnerabilities, and institutional understanding about contamination source patterns that may not be fully documented but represent critical CCS inputs.

Risk Assessment Dynamic Updates

CCS implementation demands that investigation findings trigger systematic risk assessment updates that reflect enhanced understanding of contamination vulnerabilities:

- Contamination source identification updates based on investigation findings that reveal previously unrecognized or underestimated contamination pathways requiring additional control measures or monitoring enhancements.

- Control measure effectiveness verification through post-investigation monitoring that demonstrates whether implemented corrective actions actually reduce contamination risks or require further enhancement.

- Monitoring program optimization based on investigation insights about contamination patterns that may indicate needs for additional sampling locations, modified sampling frequencies, or enhanced analytical methods.

Continuous Improvement Integration

The CCS must function as a living document that evolves based on investigation findings rather than remaining static until the next formal review cycle:

- Investigation-driven CCS updates that incorporate new contamination risk understanding into facility design assessments, process control evaluations, and personnel training requirements.

- Performance metrics integration that tracks investigation quality indicators alongside traditional contamination control metrics to ensure investigation systems themselves contribute to contamination risk reduction.

- Cross-site knowledge sharing mechanisms that enable investigation insights from one facility to enhance contamination control strategies at related manufacturing sites.

Best Practice 5: Establish Investigation Quality Metrics and Systematic Oversight

Investigation Completeness and Quality Assessment

Organizations must implement systematic approaches to ensure investigation quality and prevent the superficial analysis demonstrated by Rechon. This requires comprehensive quality metrics that evaluate both investigation process compliance and outcome effectiveness:

- Investigation completeness verification using a rubric or other standardized checklists that ensure all required investigation elements have been addressed before investigation closure. These must verify background documentation adequacy, data gathering comprehensiveness, SME assessment completion, impact evaluation thoroughness, and corrective action appropriateness.

- Root cause determination quality assessment evaluating whether investigation conclusions demonstrate scientific rigor and logical connection between identified causes and observed contamination events. This includes verification that root cause analysis employed appropriate methodologies and that conclusions can withstand independent technical review.

- Corrective action effectiveness verification through systematic post-implementation monitoring that demonstrates whether corrective actions achieved their intended contamination risk reduction objectives.

Management Review and Challenge Processes

Effective investigation oversight requires management systems that actively challenge investigation conclusions and ensure scientific rationale supports all determinations:

- Technical review panels comprising independent SMEs who evaluate investigation methodology, data interpretation, and conclusion validity before investigation closure approval for major and critical deviations. I strongly recommend this as part of qualification and re-qualification activities.

- Regulatory perspective integration ensuring investigation approaches and conclusions align with current regulatory expectations and enforcement trends rather than relying on outdated compliance interpretations.

- Cross-functional impact assessment verifying that investigation findings and corrective actions consider all affected operational areas and don’t create unintended contamination risks in other facility areas.

CAPA System Integration and Effectiveness Tracking

Investigation findings must integrate with robust CAPA systems that ensure systematic improvements rather than isolated fixes:

- Systematic improvement identification that links investigation findings to broader facility or process enhancement opportunities rather than limiting corrective actions to immediate excursion sources.

- CAPA implementation quality management including resource allocation verification, timeline adherence monitoring, and effectiveness verification protocols that ensure corrective actions achieve intended risk reduction.

- Knowledge management integration that captures investigation insights for application to similar contamination risks across the organization and incorporates lessons learned into training programs and preventive maintenance activities.

Rechon’s continued contamination issues despite previous investigations suggest their CAPA processes lacked this systematic improvement approach, treating each contamination event as isolated rather than symptoms of broader contamination control weaknesses.

The Investigation-Annex 1 Integration Challenge: Building Investigation Resilience

Holistic Contamination Risk Assessment

Contamination control requires investigation systems that function as integral components of comprehensive strategies rather than reactive compliance activities.

Design-Investigation Integration demands that investigation findings inform facility design assessments and process modification evaluations. When investigations reveal design-related contamination sources, CCS updates must address whether facility modifications or process changes can eliminate contamination risks at their source rather than relying on monitoring and control measures.

Process Knowledge Enhancement through investigation activities that systematically build organizational understanding of contamination vulnerabilities, control measure effectiveness, and operational factors that influence contamination risk profiles.

Personnel Competency Development that leverages investigation findings to identify training needs, competency gaps, and behavioral factors that contribute to contamination risks requiring systematic rather than individual corrective approaches.

Technology Integration and Future Investigation Capabilities

Advanced Monitoring and Investigation Support Systems

The increasing sophistication of regulatory expectations necessitates corresponding advances in investigation support technologies that enable more comprehensive and efficient contamination risk assessment:

Real-time monitoring integration that provides investigation teams with comprehensive environmental data streams enabling correlation analysis between contamination events and operational variables that might not be captured through traditional discrete sampling approaches.

Automated trend analysis capabilities that identify contamination patterns and correlations across multiple data sources, facility areas, and time periods that might not be apparent through manual analysis methods.

Integrated knowledge management platforms that capture investigation insights, corrective action outcomes, and operational observations in formats that enable systematic application to future contamination risk assessments and control strategy optimization.

Investigation Standardization and Quality Enhancement

Technology solutions must also address investigation process standardization and quality improvement:

Investigation workflow management systems that ensure consistent application of investigation methodologies, prevent shortcuts that compromise investigation quality, and provide audit trails demonstrating compliance with regulatory expectations.

Cross-site investigation coordination capabilities that enable investigation insights from one facility to inform contamination risk assessments and investigation approaches at related manufacturing sites.

Building Organizational Investigation Excellence

Cultural Transformation Requirements

The evolution from compliance-focused contamination investigations toward risk-based contamination control strategies requires fundamental cultural changes that extend beyond procedural updates:

Leadership commitment demonstration through resource allocation for investigation system enhancement, personnel competency development, and technology infrastructure investment that enables comprehensive contamination risk assessment rather than minimal compliance achievement.

Cross-functional collaboration enhancement that breaks down organizational silos preventing comprehensive investigation approaches and ensures investigation teams have access to all relevant operational expertise and information sources.

Continuous improvement mindset development that views contamination investigations as opportunities for systematic facility and process enhancement rather than unfortunate compliance burdens to be minimized.

Investigation as Strategic Asset

Organizations that excel in contamination investigation develop capabilities that provide competitive advantages beyond regulatory compliance:

Process optimization opportunities identification through investigation activities that reveal operational inefficiencies, equipment performance issues, and facility design limitations that, when addressed, improve both contamination control and operational effectiveness.

Risk management capability enhancement that enables proactive identification and mitigation of contamination risks before they result in regulatory scrutiny or product quality issues requiring costly remediation.

Regulatory relationship management through demonstration of investigation competence and commitment to continuous improvement that can influence regulatory inspection frequency and focus areas.

The Cost of Investigation Mediocrity: Lessons from Enforcement

Regulatory Consequences and Business Impact

Rechon’s experience demonstrates the ultimate cost of inadequate contamination investigations: comprehensive regulatory action that threatens market access and operational continuity. The FDA’s requirements for extensive remediation—including independent assessment of investigation systems, comprehensive personnel and environmental monitoring program reviews, and retrospective out-of-specification result analysis—represent exactly the kind of work that should be conducted proactively rather than reactively.

Resource Allocation and Opportunity Cost

The remediation requirements imposed on companies receiving warning letters far exceed the resource investment required for proactive investigation system development:

- Independent consultant engagement costs for comprehensive facility and system assessment that could be avoided through internal investigation capability development and systematic contamination control strategy implementation.

- Production disruption resulting from regulatory holds, additional sampling requirements, and corrective action implementation that interrupts normal manufacturing operations and delays product release.

- Market access limitations including potential product recalls, import restrictions, and regulatory approval delays that affect revenue streams and competitive positioning.

Reputation and Trust Impact

Beyond immediate regulatory and financial consequences, investigation failures create lasting reputation damage that affects customer relationships, regulatory standing, and business development opportunities:

- Customer confidence erosion when investigation failures become public through warning letters, regulatory databases, and industry communications that affect long-term business relationships.

- Regulatory relationship deterioration that can influence future inspection focus areas, approval timelines, and enforcement approaches that extend far beyond the original contamination control issues.

- Industry standing impact that affects ability to attract quality personnel, develop partnerships, and maintain competitive positioning in increasingly regulated markets.

Gap Assessment Framework: Organizational Investigation Readiness

Investigation System Evaluation Criteria

Organizations should systematically assess their investigation capabilities against current regulatory expectations and best practice standards. This assessment encompasses multiple evaluation dimensions:

- Technical Competency Assessment

- Do investigation teams possess demonstrated expertise in contamination microbiology, facility design, process engineering, and regulatory requirements?

- Are investigation methodologies standardized, documented, and consistently applied across different contamination scenarios?

- Does investigation scope routinely include comprehensive trend analysis, adjacent area assessment, and environmental correlation analysis?

- Are investigation conclusions supported by scientific rationale and independent technical review?

- Resource Adequacy Evaluation

- Are sufficient personnel resources allocated to enable comprehensive investigation completion within reasonable timeframes?

- Do investigation teams have access to necessary analytical capabilities, reference materials, and technical support resources?

- Are investigation budgets adequate to support comprehensive data gathering, expert consultation, and corrective action implementation?

- Does management demonstrate commitment through resource allocation and investigation priority establishment?

- Integration and Effectiveness Assessment

- Are investigation findings systematically integrated into contamination control strategy updates and facility risk assessments?

- Do CAPA systems ensure investigation insights drive systematic improvements rather than isolated fixes?

- Are investigation outcomes tracked and verified to confirm contamination risk reduction achievement?

- Do knowledge management systems capture and apply investigation insights across the organization?

From Investigation Adequacy to Investigation Excellence

Rechon Life Science’s experience serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of investigation mediocrity, but it also illustrates the transformation potential inherent in comprehensive contamination control strategy implementation. When organizations invest in systematic investigation capabilities—encompassing proper team composition, comprehensive analytical approaches, effective knowledge management, and continuous improvement integration—they build competitive advantages that extend far beyond regulatory compliance.

The key insight emerging from regulatory enforcement patterns is that contamination control has evolved from a specialized technical discipline into a comprehensive business capability that affects every aspect of pharmaceutical manufacturing. The quality of an organization’s contamination investigations often determines whether contamination events become learning opportunities that strengthen operations or regulatory nightmares that threaten business continuity.

For quality professionals responsible for contamination control, the message is unambiguous: investigation excellence is not an optional enhancement to existing compliance programs—it’s a fundamental requirement for sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing in the modern regulatory environment. The organizations that recognize this reality and invest accordingly will find themselves well-positioned not only for regulatory success but for operational excellence that drives competitive advantage in increasingly complex global markets.

The regulatory landscape has fundamentally changed, and traditional approaches to contamination investigation are no longer sufficient. Organizations must decide whether to embrace the investigation excellence imperative or face the consequences of continuing with approaches that regulatory agencies have clearly indicated are inadequate. The choice is clear, but the window for proactive transformation is narrowing as regulatory expectations continue to evolve and enforcement intensifies.

The question facing every pharmaceutical manufacturer is not whether contamination control investigations will face increased scrutiny—it’s whether their investigation systems will demonstrate the excellence necessary to transform regulatory challenges into competitive advantages. Those that choose investigation excellence will thrive; those that don’t will join Rechon Life Science and others in explaining their investigation failures to regulatory agencies rather than celebrating their contamination control successes in the marketplace.