Good documentation practices when documenting Work as Prescribed stresses the clarity, accuracy, thoroughness and control of the procedural instruction being written.

Clarity and Accuracy: Documentation should be clear and free from errors, ensuring that instructions are understood and followed correctly. This aligns with the concept of being precise in documentation.

Thoroughness: All relevant activities impacting quality should be recorded and controlled, indicating a need for comprehensive documentation practices.

Control and Integrity: The need for strict control over documentation to maintain integrity, accuracy, and availability throughout its lifecycle.

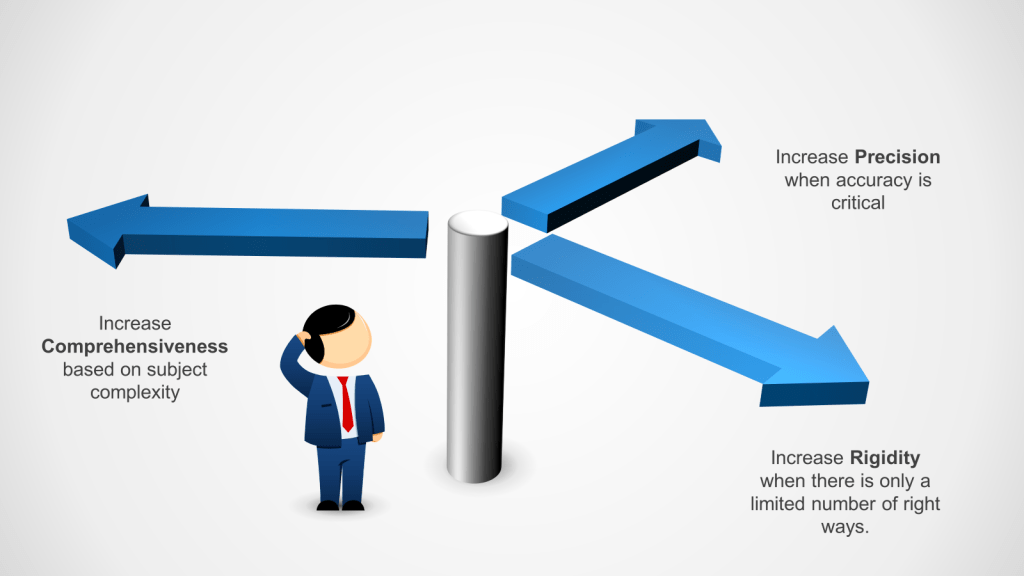

To meet these requirements we leverage three writing principles of precise, comprehensive and rigid.

| Type of Instruction | Definition | Attributes | When Needed | Why | Differences | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precise | Exact and accurate, leaving little room for interpretation. | – Specific – Detailed – Unambiguous | When accuracy is critical, such as in scientific experiments or programming. | Regulatory agencies require precise documentation to ensure tasks are performed consistently and correctly | Focuses on exactness and clarity, ensuring tasks are performed without deviation. | Instructions for assembling a computer, specifying exact components and steps. |

| Comprehensive | Complete and covering all necessary aspects of a task. | – Thorough – Inclusive – Exhaustive | When a task is complex and requires understanding of all components, such as in training manuals. | Comprehensive SOPs are crucial for ensuring all aspects of a process are covered, ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements. | Provides a full overview, ensuring no part of the task is overlooked. | Employee onboarding manual covering company policies, procedures, and culture. |

| Rigid | Strict and inflexible, not allowing for changes. | – Fixed – Inflexible – Consistent | When safety and compliance are paramount, such as batch records | Rigid instructions ensure compliance with strict regulatory standards. | Ensures consistency and adherence to specific protocols, minimizing risks. | Safety procedures for operating heavy machinery, with no deviations allowed. |

When writing documents based on cognitive principles these three are often excellent for detailed task design but there are significant trade-offs inherent in these attributes when we codify knowledge:

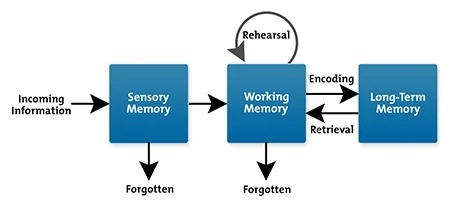

- The more comprehensive the instructions, the less likely that they can be absorbed, understood, and remembered by those responsible for execution – which is why it is important these instructions are followed at time of execution. Moreover, comprehensive instructions also risk can dilute the sense of responsibility felt by the person executing.

- The more precise the instructions, the less they allow for customization or the exercise of employee initiative.

- The more rigid the instructions, the less they will be able to evolve spontaneously as circumstances change. They require rigorous change management.

This means these tools are really good for complicated executions that must follow a specific set of steps. Ideal for equipment operations, testing, batch records. But as we shade into complex processes, which relies on domain knowledge, we start decreasing the rigidity, lowering the degree of precision, and walking a fine line on comprehensiveness.

Where organizations continue to struggle is in this understanding that it is not one size fits all. Every procedure is on a continuum and the level of comprehensiveness, precision and rigidity change as a result. Processes involving human judgement, customization for specific needs, or adaptations for changing circumstances should be written to a different standard than those involving execution of a test. It is also important to remember that a document may require high comprehensiveness, medium precision and low rigidity (for example a validation process).

Remember to use them with other tools for document writing. The goal here is to write documents that are usable to reach the necessary outcome.