Quality management requires a sophisticated blend of skills that transcend traditional audit and compliance approaches. As organizations increasingly recognize quality systems as living entities rather than static frameworks, quality professionals must evolve from mere enforcers to nurturers—from auditors to gardeners. This paradigm shift demands a new approach to competency development that embraces both technical expertise and adaptive capabilities.

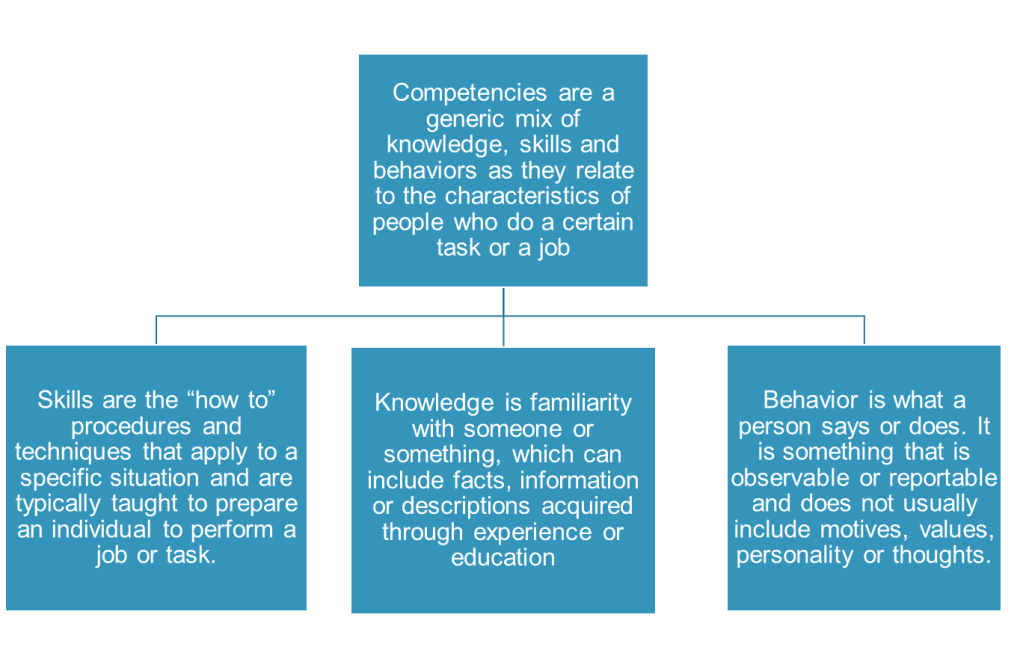

Building Competencies: The Integration of Skills, Knowledge, and Behavior

A comprehensive competency framework for quality professionals must recognize that true competency is more than a simple checklist of abilities. Rather, it represents the harmonious integration of three critical elements: skills, knowledge, and behaviors. Understanding how these elements interact and complement each other is essential for developing quality professionals who can thrive as “system gardeners” in today’s complex organizational ecosystems.

The Competency Triad

Competencies can be defined as the measurable or observable knowledge, skills, abilities, and behaviors critical to successful job performance. They represent a holistic approach that goes beyond what employees can do to include how they apply their capabilities in real-world contexts.

Knowledge: The Foundation of Understanding

Knowledge forms the theoretical foundation upon which all other aspects of competency are built. For quality professionals, this includes:

- Comprehension of regulatory frameworks and compliance requirements

- Understanding of statistical principles and data analysis methodologies

- Familiarity with industry-specific processes and technical standards

- Awareness of organizational systems and their interconnections

Knowledge is demonstrated through consistent application to real-world scenarios, where quality professionals translate theoretical understanding into practical solutions. For example, a quality professional might demonstrate knowledge by correctly interpreting a regulatory requirement and identifying its implications for a manufacturing process.

Skills: The Tools for Implementation

Skills represent the practical “how-to” abilities that quality professionals use to implement their knowledge effectively. These include:

- Technical skills like statistical process control and data visualization

- Methodological skills such as root cause analysis and risk assessment

- Social skills including facilitation and stakeholder management

- Self-management skills like prioritization and adaptability

Skills are best measured through observable performance in relevant contexts. A quality professional might demonstrate skill proficiency by effectively facilitating a cross-functional investigation meeting that leads to meaningful corrective actions.

Behaviors: The Expression of Competency

Behaviors are the observable actions and reactions that reflect how quality professionals apply their knowledge and skills in practice. These include:

- Demonstrating curiosity when investigating deviations

- Showing persistence when facing resistance to quality initiatives

- Exhibiting patience when coaching others on quality principles

- Displaying integrity when reporting quality issues

Behaviors often distinguish exceptional performers from average ones. While two quality professionals might possess similar knowledge and skills, the one who consistently demonstrates behaviors aligned with organizational values and quality principles will typically achieve superior results.

Building an Integrated Competency Development Approach

To develop well-rounded quality professionals who embody all three elements of competency, organizations should:

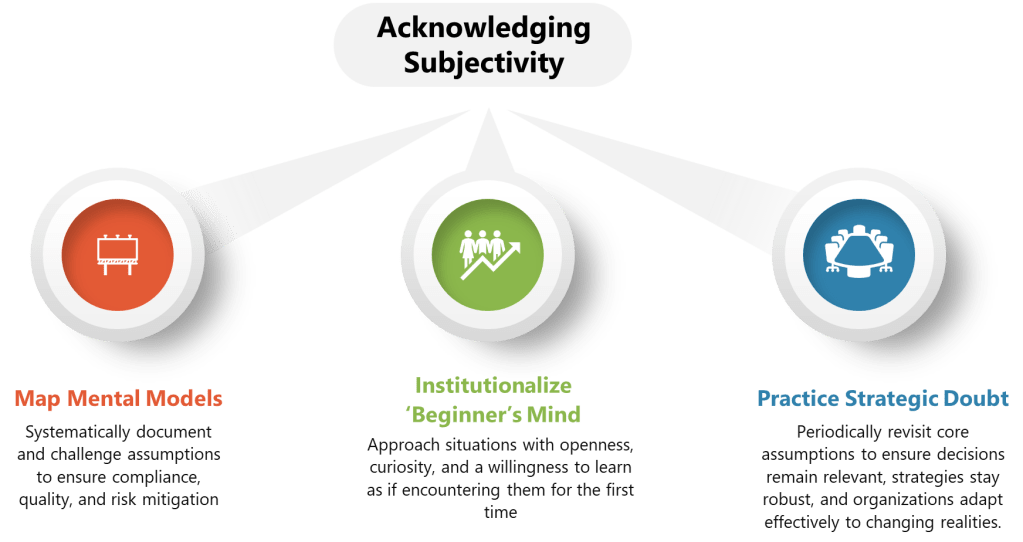

- Map the Competency Landscape: Create a comprehensive inventory of the knowledge, skills, and behaviors required for each quality role, categorized by proficiency level.

- Implement Multi-Modal Development: Recognize that different competency elements require different development approaches:

- Knowledge is often best developed through structured learning, reading, and formal education

- Skills typically require practice, coaching, and experiential learning

- Behaviors are shaped through modeling, feedback, and reflective practice

- Assess Holistically: Develop assessment methods that evaluate all three elements:

- Knowledge assessments through tests, case studies, and discussions

- Skill assessments through demonstrations, simulations, and work products

- Behavioral assessments through observation, peer feedback, and self-reflection

- Create Developmental Pathways: Design career progression frameworks that clearly articulate how knowledge, skills, and behaviors should evolve as quality professionals advance from foundational to leadership roles.

By embracing this integrated approach to competency development, organizations can nurture quality professionals who not only know what to do and how to do it, but who also consistently demonstrate the behaviors that make quality initiatives successful. These professionals will be equipped to serve as true “system gardeners,” cultivating environments where quality naturally flourishes rather than merely enforcing compliance with standards.

Understanding the Four Dimensions of Professional Skills

A comprehensive competency framework for quality professionals should address four fundamental skill dimensions that work in harmony to create holistic expertise:

Technical Skills: The Roots of Quality Expertise

Technical skills form the foundation upon which all quality work is built. For quality professionals, these specialized knowledge areas provide the essential tools needed to assess, measure, and improve systems.

Examples for Quality Gardeners:

- Mastery of statistical process control and data analysis methodologies

- Deep understanding of regulatory requirements and compliance frameworks

- Proficiency in quality management software and digital tools

- Knowledge of industry-specific technical processes (e.g., aseptic processing, sterilization validation, downstream chromatography)

Technical skills enable quality professionals to diagnose system health with precision—similar to how a gardener understands soil chemistry and plant physiology.

Methodological Skills: The Framework for System Cultivation

Methodological skills represent the structured approaches and techniques that quality professionals use to organize their work. These skills provide the scaffolding that supports continuous improvement and systematic problem-solving.

Examples for Quality Gardeners:

- Application of problem solving methodologies

- Risk management framework, methodology and and tools

- Design and execution of effective audit programs

- Knowledge management to capture insights and lessons learned

As gardeners apply techniques like pruning, feeding, and crop rotation, quality professionals use methodological skills to cultivate environments where quality naturally thrives.

Social Skills: Nurturing Collaborative Ecosystems

Social skills facilitate the human interactions necessary for quality to flourish across organizational boundaries. In living quality systems, these skills help create an environment where collaboration and improvement become cultural norms.

Examples for Quality Gardeners:

- Coaching stakeholders rather than policing them

- Facilitating cross-functional improvement initiatives

- Mediating conflicts around quality priorities

- Building trust through transparent communication

- Inspiring leadership that emphasizes quality as shared responsibility

Just as gardeners create environments where diverse species thrive together, quality professionals with strong social skills foster ecosystems where teams naturally collaborate toward excellence.

Self-Skills: Personal Adaptability and Growth

Self-skills represent the quality professional’s ability to manage themselves effectively in dynamic environments. These skills are especially crucial in today’s volatile and complex business landscape.

Examples for Quality Gardeners:

- Adaptability to changing regulatory landscapes and business priorities

- Resilience when facing resistance to quality initiatives

- Independent decision-making based on principles rather than rules

- Continuous personal development and knowledge acquisition

- Working productively under pressure

Like gardeners who must adapt to changing seasons and unexpected weather patterns, quality professionals need strong self-management skills to thrive in unpredictable environments.

| Dimension | Definition | Examples | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Skill | Referring to the specialized knowledge and practical skills | – Mastering data analysis – Understanding aseptic processing or freeze drying | Fundamental for any professional role; influences the ability to effectively perform specialized tasks |

| Methodological Skill | Ability to apply appropriate techniques and methods | – Applying Scrum or Lean Six Sigma – Documenting and transferring insights into knowledge | Essential to promote innovation, strategic thinking, and investigation of deviations |

| Social Skill | Skills for effective interpersonal interactions | – Promoting collaboration – Mediating team conflicts – Inspiring leadership | Important in environments that rely on teamwork, dynamics, and culture |

| Self-Skill | Ability to manage oneself in various professional contexts | – Adapting to a fast-paced work environment – Working productively under pressure – Independent decision-making | Crucial in roles requiring a high degree of autonomy, such as leadership positions or independent work environments |

Developing a Competency Model for Quality Gardeners

Building an effective competency model for quality professionals requires a systematic approach that aligns individual capabilities with organizational needs.

Step 1: Define Strategic Goals and Identify Key Roles

Begin by clearly articulating how quality contributes to organizational success. For a “living systems” approach to quality, goals might include:

- Cultivating adaptive quality systems that evolve with the organization

- Building resilience to regulatory changes and market disruptions

- Fostering a culture where quality is everyone’s responsibility

From these goals, identify the critical roles needed to achieve them, such as:

- Quality System Architects who design the overall framework

- Process Gardeners who nurture specific quality processes

- Cross-Pollination Specialists who transfer best practices across departments

- System Immunologists who identify and respond to potential threats

Given your organization, you probably will have more boring titles than these. I certainly do, but it is still helpful to use the names when planning and imagining.

Step 2: Identify and Categorize Competencies

For each role, define the specific competencies needed across the four skill dimensions. For example:

Quality System Architect

- Technical: Understanding of regulatory frameworks and system design principles

- Methodological: Expertise in process mapping and system integration

- Social: Ability to influence across the organization and align diverse stakeholders

- Self: Strategic thinking and long-term vision implementation

Process Gardener

- Technical: Deep knowledge of specific processes and measurement systems

- Methodological: Proficiency in continuous improvement and problem-solving techniques

- Social: Coaching skills and ability to build process ownership

- Self: Patience and persistence in nurturing gradual improvements

Step 3: Create Behavioral Definitions

Develop clear behavioral indicators that demonstrate proficiency at different levels. For example, for the competency “Cultivating Quality Ecosystems”:

Foundational level: Understands basic principles of quality culture and can implement prescribed improvement tools

Intermediate level: Adapts quality approaches to fit specific team environments and facilitates process ownership among team members

Advanced level: Creates innovative approaches to quality improvement that harness the natural dynamics of the organization

Leadership level: Transforms organizational culture by embedding quality thinking into all business processes and decision-making structures

Step 4: Map Competencies to Roles and Development Paths

Create a comprehensive matrix that aligns competencies with roles and shows progression paths. This allows individuals to visualize their development journey and organizations to identify capability gaps.

For example:

| Competency | Quality Specialist | Process Gardener | Quality System Architect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Analysis | Intermediate | Advanced | Intermediate |

| Process Improvement | Foundational | Advanced | Intermediate |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Foundational | Intermediate | Advanced |

| Systems Thinking | Foundational | Intermediate | Advanced |

Building a Training Plan for Quality Gardeners

A well-designed training plan translates the competency model into actionable development activities for each individual.

Step 1: Job Description Analysis

Begin by analyzing job descriptions to identify the specific processes and roles each quality professional interacts with. For example, a Quality Control Manager might have responsibilities for:

- Leading inspection readiness activities

- Supporting regulatory site inspections

- Participating in vendor management processes

- Creating and reviewing quality agreements

- Managing deviations, change controls, and CAPAs

Step 2: Role Identification

For each job responsibility, identify the specific roles within relevant processes:

| Process | Role |

|---|---|

| Inspection Readiness | Lead |

| Regulatory Site Inspections | Support |

| Vendor Management | Participant |

| Quality Agreements | Author/Reviewer |

| Deviation/CAPA | Author/Reviewer/Approver |

| Change Control | Author/Reviewer/Approver |

Step 3: Training Requirements Mapping

Working with process owners, determine the training requirements for each role. Consider creating modular curricula that build upon foundational skills:

Foundational Quality Curriculum: Regulatory basics, quality system overview, documentation standards

Technical Writing Curriculum: Document creation, effective review techniques, technical communication

Process-Specific Curricula: Tailored training for each process (e.g., change control, deviation management)

Step 4: Implementation and Evolution

Recognize that like the quality systems they support, training plans should evolve over time:

- Update as job responsibilities change

- Adapt as processes evolve

- Incorporate feedback from practical application

- Balance formal training with experiential learning opportunities

Cultivating Excellence Through Competency Development

Building a competency framework aligned with the “living systems” view of quality management transforms how organizations approach quality professional development. By nurturing technical, methodological, social, and self-skills in balance, organizations create quality professionals who act as true gardeners—professionals who cultivate environments where quality naturally flourishes rather than imposing it through rigid controls.

As quality systems continue to evolve, the most successful organizations will be those that invest in developing professionals who can adapt and thrive amid complexity. These “quality gardeners” will lead the way in creating systems that, like healthy ecosystems, become more resilient and vibrant over time.

Applying the Competency Model

For organizational leadership in quality functions, adopting a competency model is a transformative step toward building a resilient, adaptive, and high-performing team—one that nurtures quality systems as living, evolving ecosystems rather than static structures. The competency model provides a unified language and framework to define, develop, and measure the capabilities needed for success in this gardener paradigm.

The Four Dimensions of the Competency Model

| Competency Model Dimension | Definition | Examples | Strategic Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Competency | Specialized knowledge and practical abilities required for quality roles | – Understanding aseptic processing – Mastering root cause analysis – Operating quality management software | Fundamental for effective execution of specialized quality tasks and ensuring compliance |

| Methodological Competency | Ability to apply structured techniques, frameworks, and continuous improvement methods | – Applying Lean Six Sigma – Documenting and transferring process knowledge – Designing audit frameworks | Drives innovation, strategic problem-solving, and systematic improvement of quality processes |

| Social Competency | Skills for effective interpersonal interactions and collaboration | – Facilitating cross-functional teams – Mediating conflicts – Coaching and inspiring others | Essential for cultivating a culture of shared ownership and teamwork in quality initiatives |

| Self-Competency | Capacity to manage oneself, adapt, and demonstrate resilience in dynamic environments | – Adapting to change – Working under pressure – Exercising independent judgment | Crucial for autonomy, leadership, and thriving in evolving, complex quality environments |

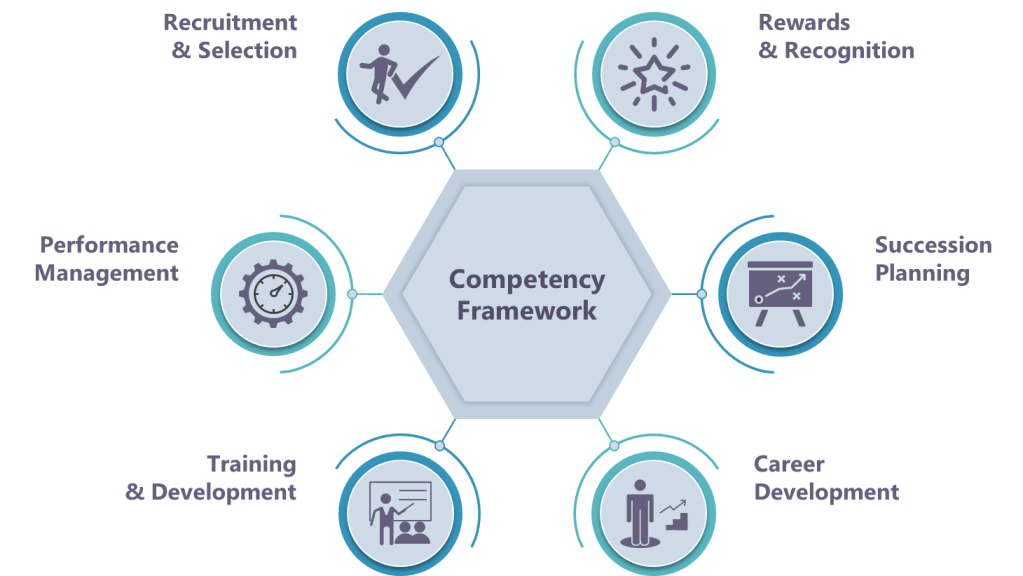

Leveraging the Competency Model Across Organizational Practices

To fully realize the gardener approach, integrate the competency model into every stage of the talent lifecycle:

Recruitment and Selection

- Role Alignment: Use the competency model to define clear, role-specific requirements—ensuring candidates are evaluated for technical, methodological, social, and self-competencies, not just past experience.

- Behavioral Interviewing: Structure interviews around observable behaviors and scenarios that reflect the gardener mindset (e.g., “Describe a time you nurtured a process improvement across teams”).

Rewards and Recognition

- Competency-Based Rewards: Recognize and reward not only outcomes, but also the demonstration of key competencies—such as collaboration, adaptability, and continuous improvement behaviors.

- Transparency: Use the competency model to provide clarity on what is valued and how employees can be recognized for growing as “quality gardeners.”

Performance Management

- Objective Assessment: Anchor performance reviews in the competency model, focusing on both results and the behaviors/skills that produced them.

- Feedback and Growth: Provide structured, actionable feedback linked to specific competencies, supporting a culture of continuous development and accountability.

Training and Development

- Targeted Learning: Identify gaps at the individual and team level using the competency model, and develop training programs that address all four competency dimensions.

- Behavioral Focus: Ensure training goes beyond knowledge transfer, emphasizing the practical application and demonstration of new competencies in real-world settings.

Career Development

- Progression Pathways: Map career paths using the competency model, showing how employees can grow from foundational to advanced levels in each competency dimension.

- Self-Assessment: Empower employees to self-assess against the model, identify growth areas, and set targeted development goals.

Succession Planning

- Future-Ready Talent: Use the competency model to identify and develop high-potential employees who exhibit the gardener mindset and can step into critical roles.

- Capability Mapping: Regularly assess organizational competency strengths and gaps to ensure a robust pipeline of future leaders aligned with the gardener philosophy.

Leadership Call to Action

For quality organizations moving to the gardener approach, the competency model is a strategic lever. By consistently applying the model across recruitment, recognition, performance, development, career progression, and succession, leadership ensures the entire organization is equipped to nurture adaptive, resilient, and high-performing quality systems.

This integrated approach creates clarity, alignment, and a shared vision for what excellence looks like in the gardener era. It enables quality professionals to thrive as cultivators of improvement, collaboration, and innovation—ensuring your quality function remains vital and future-ready.