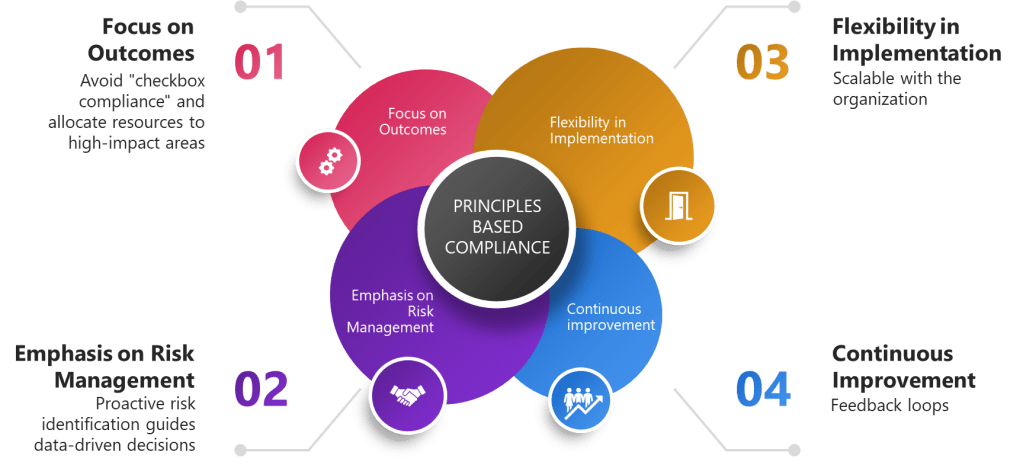

You will often hear discussions of how a principles-based approach to compliance, focusing on adhering to core principles rather than rigid, prescriptive rules, allowing for greater flexibility and innovation in GMP environments. A term often used in technology implementations, it is at once a lot to unpack and a salesmen’s pitch that might not be out of place for a monorail.

Understanding Principles-Based Compliance

Principles-based compliance is an approach that emphasizes the underlying intent of regulations rather than strict adherence to specific rules. It provides a framework for decision-making that allows organizations to adapt to changing technologies and processes while maintaining the spirit of GXP requirements.

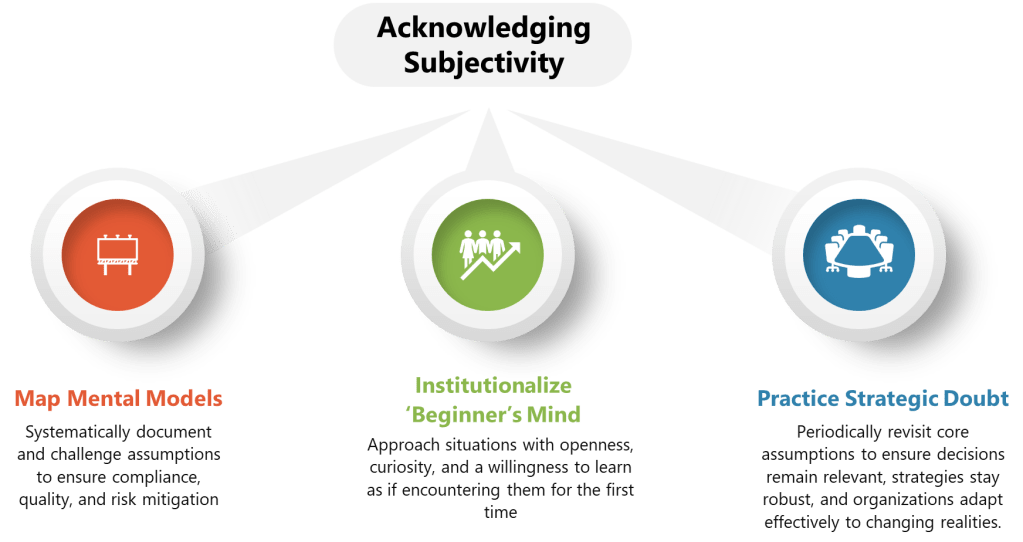

Key aspects of principles-based compliance include:

- Focus on outcomes rather than processes

- Emphasis on risk management

- Flexibility in implementation

- Continuous improvement

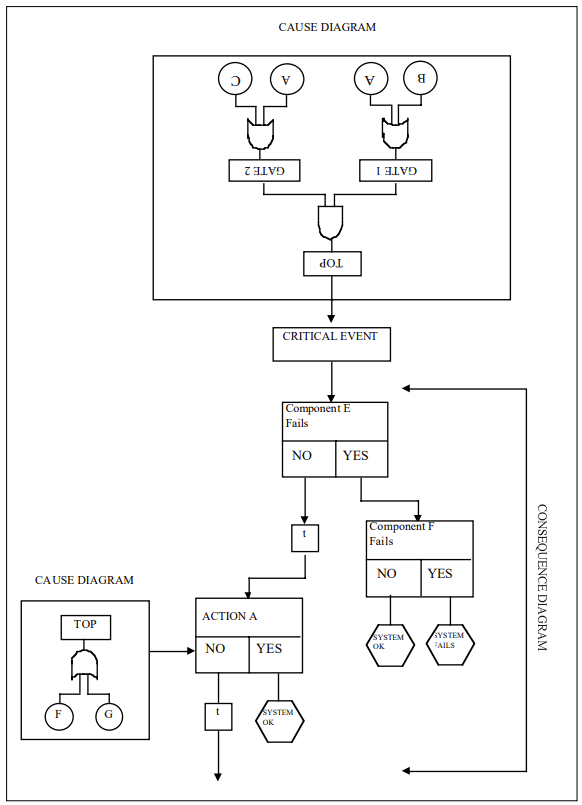

At it’s heart, and when done right, these are the principles of risk based approaches such as ASTM E2500.

Dangers of Focusing on Outcomes Rather than Processes

Focusing on outcomes rather than processes in principles-based compliance introduces several risks that organizations must carefully manage. One major concern is the lack of clear guidance. Outcome-focused compliance provides flexibility but can lead to ambiguity, as employees may struggle to interpret how to achieve the desired results. This ambiguity can result in inconsistent implementation or “herding behavior,” where organizations mimic peers’ actions rather than adhering to the principles, potentially undermining regulatory objectives.

Another challenge lies in measuring outcomes. If outcomes are not measurable, regulators may struggle to assess compliance effectively, leaving room for discrepancies in interpretation and enforcement.

The risk of non-compliance also increases when organizations focus solely on outcomes. Insufficient monitoring and enforcement can allow organizations to interpret desired outcomes in ways that prioritize their own interests over regulatory intent, potentially leading to non-compliance.

Finally, accountability becomes more challenging under this approach. Principles-based compliance relies heavily on organizational integrity and judgment. If a company’s culture does not support ethical decision-making, there is a risk that short-term gains will be prioritized over long-term compliance goals. While focusing on outcomes offers flexibility and encourages innovation, these risks highlight the importance of balancing principles-based compliance with adequate guidance, monitoring, and enforcement mechanisms to ensure regulatory objectives are met effectively.

Benefits for Technology Implementation

Adopting a principles-based approach to compliance can significantly benefit technology implementation in GMP environments:

1. Adaptability to Emerging Technologies

Principles-based compliance allows organizations to more easily integrate new technologies without being constrained by outdated, prescriptive regulations. This flexibility is crucial in rapidly evolving fields like pharmaceuticals and medical devices.

2. Streamlined Validation Processes

By focusing on the principles of data integrity and product quality, organizations can streamline their validation processes for new technologies. This approach can lead to faster implementation times and reduced costs.

3. Enhanced Risk Management

A principles-based approach encourages a more holistic view of risk, allowing organizations to allocate resources more effectively and focus on areas that have the most significant impact on product quality and patient safety.

4. Fostering Innovation

By providing more flexibility in how compliance is achieved, principles-based compliance can foster a culture of innovation within GMP environments. This can lead to improved processes and ultimately better products.

Implementing Principles-Based Compliance

To successfully implement a principles-based approach to compliance in GMP environments:

- Develop a Strong Quality Culture: Ensure that all employees understand the principles behind GMP regulations and their importance in maintaining product quality and safety.

- Invest in Training: Provide comprehensive training to employees at all levels to ensure they can make informed decisions aligned with GMP principles.

- Leverage Technology: Implement robust quality management systems (QMS) that support principles-based compliance by providing flexibility in process design while maintaining strict control over critical quality attributes.

- Encourage Continuous Improvement: Foster a culture of continuous improvement, where processes are regularly evaluated and optimized based on GMP principles rather than rigid rules.

- Engage with Regulators: Maintain open communication with regulatory bodies to ensure alignment on the interpretation and application of GMP principles.

Challenges and Considerations

Principles-based compliance frameworks, while advantageous for their adaptability and focus on outcomes, introduce distinct challenges that organizations must navigate thoughtfully.

Interpretation Variability poses a significant hurdle, as the flexibility inherent in principles-based systems can lead to inconsistent implementation. Without prescriptive rules, organizations—or even departments within the same company—may interpret regulatory principles differently based on their risk appetite, operational context, or cultural priorities. For example, a biotech firm’s R&D team might prioritize innovation in process optimization to meet quality outcomes, while the manufacturing unit adheres to traditional methods to minimize deviation risks. This fragmentation can create compliance gaps, operational inefficiencies, or even regulatory scrutiny if interpretations diverge from authorities’ expectations. In industries like pharmaceuticals, where harmonization with standards such as ICH Q10 is critical, subjective interpretations of principles like “continual improvement” could lead to disputes during audits or inspections.

Increased Responsibility shifts the burden of proof onto organizations to justify their compliance strategies. Unlike rules-based systems, where adherence to checklists suffices, principles-based frameworks demand robust documentation, data-driven rationale, and proactive risk assessments to demonstrate alignment with regulatory intent. . Additionally, employees at all levels must understand the ethical and operational “why” behind decisions, necessitating ongoing training and cultural alignment to prevent shortcuts or misinterpretations.

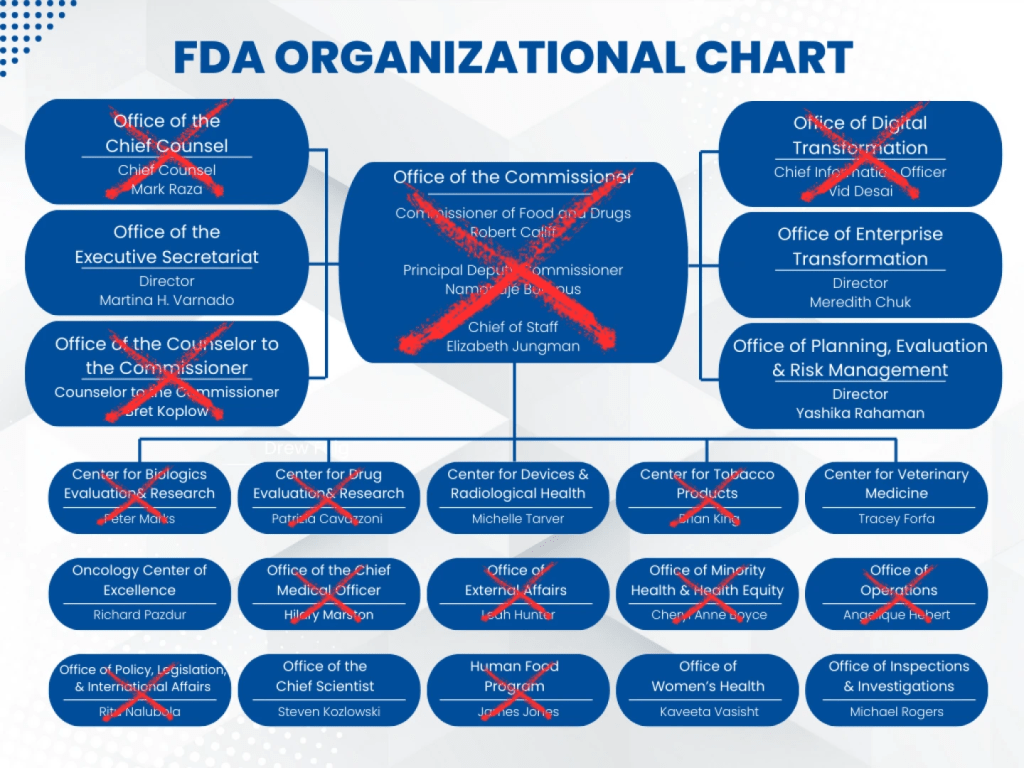

Regulatory Alignment becomes more complex in a principles-based environment, as expectations evolve alongside technological and market shifts. Regulators like the FDA or EMA often provide high-level guidance (e.g., “ensure data integrity”) but leave specifics open to interpretation. Organizations must engage in continuous dialogue with authorities to avoid misalignment—a challenge exemplified by the 2023 EMA guidance on AI in drug development, which emphasized transparency without defining technical thresholds. Companies using machine learning for clinical trial analysis had to iteratively refine their validation approaches through pre-submission meetings to avoid approval delays. Furthermore, global operations face conflicting regional priorities; a therapy compliant with the FDA’s patient-centric outcomes framework might clash with the EU’s stricter environmental sustainability mandates. Staying aligned requires investing in regulatory intelligence teams, participating in industry working groups, and sometimes advocating for clearer benchmarks to bridge principle-to-practice gaps.

These challenges underscore the need for organizations to balance flexibility with rigor, ensuring that principles-based compliance does not compromise accountability or patient safety in pursuit of innovation.

Conclusion

Principles-based compliance can represent a paradigm shift in how organizations approach GMP in technology-driven environments. By focusing on the core principles of quality, safety, and efficacy, this approach enables greater flexibility and innovation in implementing new technologies while maintaining rigorous standards of compliance.

Embracing principles-based compliance can provide a competitive advantage, allowing organizations to adapt more quickly to technological advancements while ensuring the highest standards of product quality and patient safety. However, successful implementation requires a strong quality culture, comprehensive training, and ongoing engagement with regulatory bodies to ensure alignment and consistency in interpretation.

By adopting a principles-based approach to compliance, organizations can create a more agile and innovative GMP environment that is well-equipped to meet the challenges of modern manufacturing while upholding the fundamental principles of product quality and safety.