The ECA recently wrote about a recurring theme across 2025 FDA warning letters that puts the spotlight on the troubling reality that inadequate training remains a primary driver of compliance failures across pharmaceutical manufacturing. Recent enforcement actions against companies like Rite-Kem Incorporated, Yangzhou Sion Commodity, and Staska Pharmaceuticals consistently cite violations of 21 CFR 211.25, specifically failures to ensure personnel receive adequate education, training, and experience for their assigned functions. These patterns, which are supported by deep dives into compliance data, indicate that traditional training approaches—focused on knowledge transfer rather than behavior change—are fundamentally insufficient for building robust quality systems. The solution requires a shift toward falsifiable quality systems where training programs become testable hypotheses about organizational performance, integrated with risk management principles that anticipate and prevent failures, and designed to drive quality maturity through measurable learning outcomes.

The Systemic Failure of Traditional Training Approaches

These regulatory actions reflect deeper systemic issues than mere documentation failures. They reveal organizations operating with unfalsifiable assumptions about training effectiveness—assumptions that cannot be tested, challenged, or proven wrong. Traditional training programs operate on the premise that information transfer equals competence development, yet regulatory observations consistently show this assumption fails under scrutiny. When the FDA investigates training effectiveness, they discover organizations that cannot demonstrate actual behavioral change, knowledge retention, or performance improvement following training interventions.

The Hidden Costs of Quality System Theater

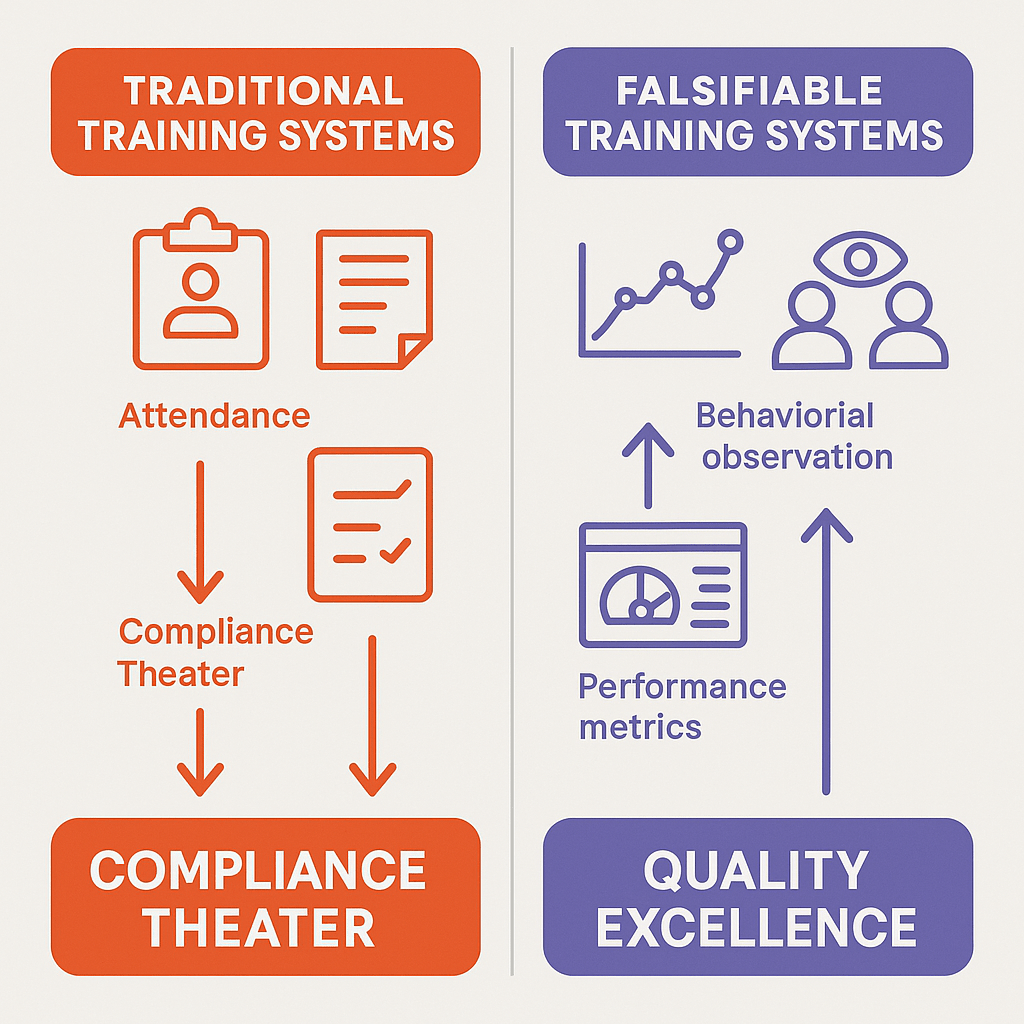

As discussed before, many pharmaceutical organizations engage in what can be characterized as theater. In this case the elaborate systems of documentation, attendance tracking, and assessment create the appearance of comprehensive training while failing to drive actual performance improvements. This phenomenon manifests in several ways: annual training requirements that focus on seat time rather than competence development, generic training modules disconnected from specific job functions, and assessment methods that test recall rather than application. These approaches persist because they are unfalsifiable—they cannot be proven ineffective through normal business operations.

The evidence suggests that training theater is pervasive across the industry. Organizations invest significant resources in learning management systems, course development, and administrative overhead while failing to achieve the fundamental objective: ensuring personnel can perform their assigned functions competently and consistently. As architects of quality systems we need to increasingly scrutinizing the outcomes of training programs rather than their inputs, demanding evidence that training actually enables personnel to perform their functions effectively.

Falsifiable Quality Systems: A New Paradigm for Training Excellence

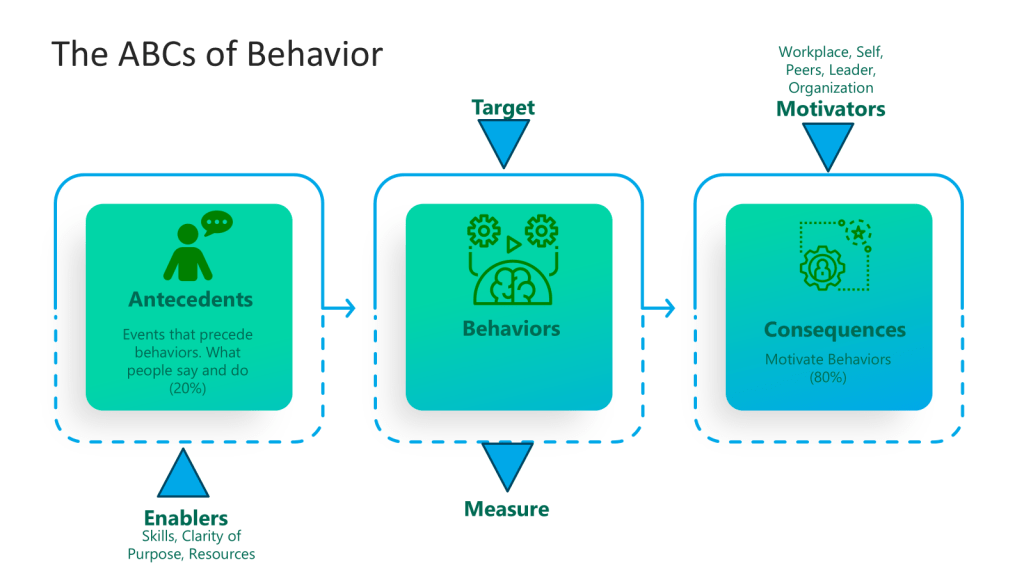

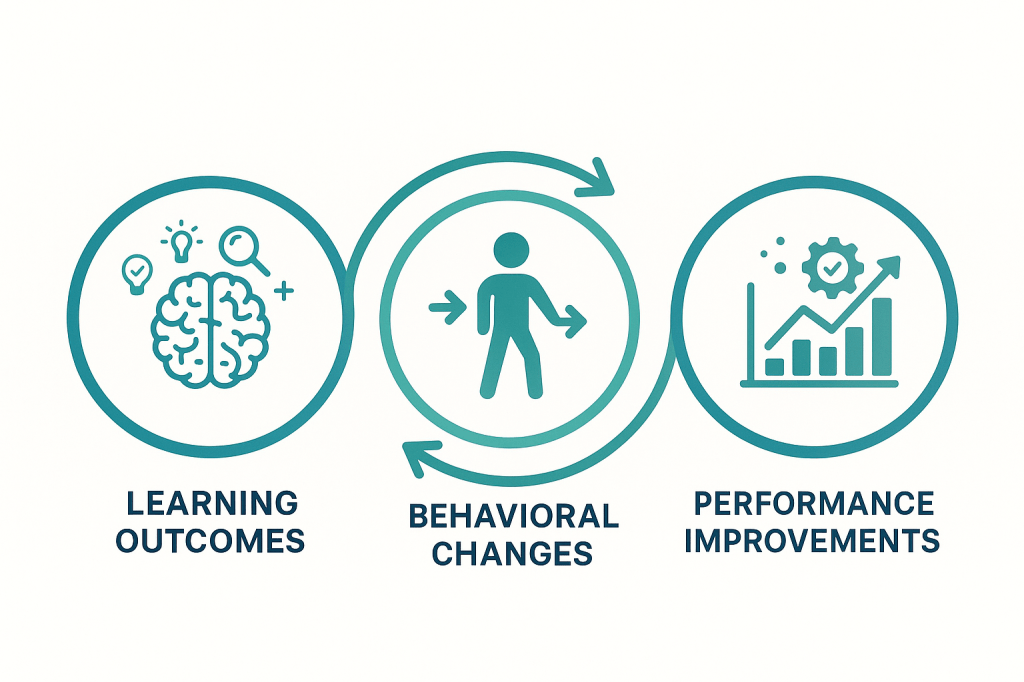

Falsifiable quality systems represent a departure from traditional compliance-focused approaches to pharmaceutical quality management. Falsifiable systems generate testable predictions about organizational behavior that can be proven wrong through empirical observation. In the context of training, this means developing programs that make specific, measurable predictions about learning outcomes, behavioral changes, and performance improvements—predictions that can be rigorously tested and potentially falsified.

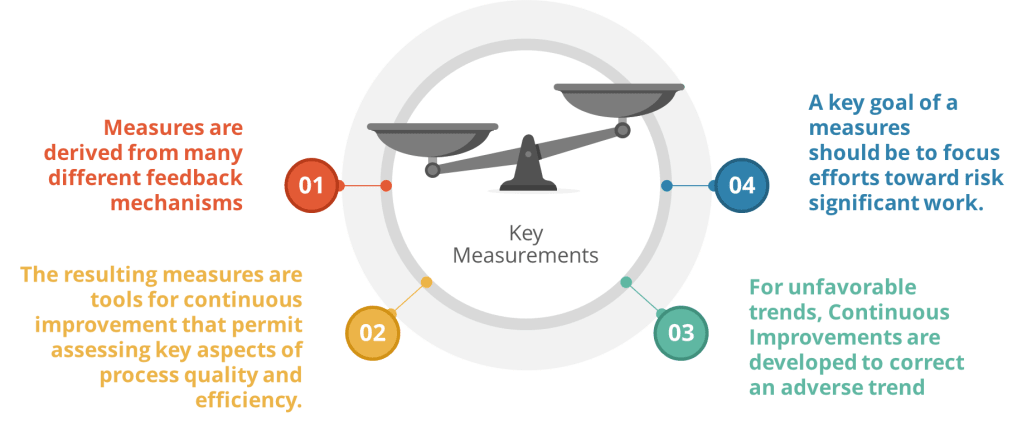

Traditional training programs operate as closed systems that confirm their own effectiveness through measures like attendance rates, completion percentages, and satisfaction scores. Falsifiable training systems, by contrast, generate external predictions about performance that can be independently verified. For example, rather than measuring training satisfaction, a falsifiable system might predict specific reductions in deviation rates, improvements in audit performance, or increases in proactive risk identification following training interventions.

The philosophical shift from unfalsifiable to falsifiable training systems addresses a fundamental problem in pharmaceutical quality management: the tendency to confuse activity with achievement. Traditional training systems measure inputs—hours of training delivered, number of personnel trained, compliance with training schedules—rather than outputs—behavioral changes, performance improvements, and quality outcomes. This input focus creates systems that can appear successful while failing to achieve their fundamental objectives.

Predictive Training Models

Falsifiable training systems begin with the development of predictive models that specify expected relationships between training interventions and organizational outcomes. These models must be specific enough to generate testable hypotheses while remaining practical for implementation in pharmaceutical manufacturing environments. For example, a predictive model for CAPA training might specify that personnel completing an enhanced root cause analysis curriculum will demonstrate a 25% improvement in investigation depth scores and a 40% reduction in recurring issues within six months of training completion.

The development of predictive training models requires deep understanding of the causal mechanisms linking training inputs to quality outcomes. This understanding goes beyond surface-level correlations to identify the specific knowledge, skills, and behaviors that drive superior performance. For root cause analysis training, the predictive model might specify that improved performance results from enhanced pattern recognition abilities, increased analytical rigor in evidence evaluation, and greater persistence in pursuing underlying causes rather than superficial explanations.

Predictive models must also incorporate temporal dynamics, recognizing that different aspects of training effectiveness manifest over different time horizons. Initial learning might be measurable through knowledge assessments administered immediately following training. Behavioral change might become apparent within 30-60 days as personnel apply new techniques in their daily work. Organizational outcomes like deviation reduction or audit performance improvement might require 3-6 months to become statistically significant. These temporal considerations are essential for designing evaluation systems that can accurately assess training effectiveness across multiple dimensions.

Measurement Systems for Learning Verification

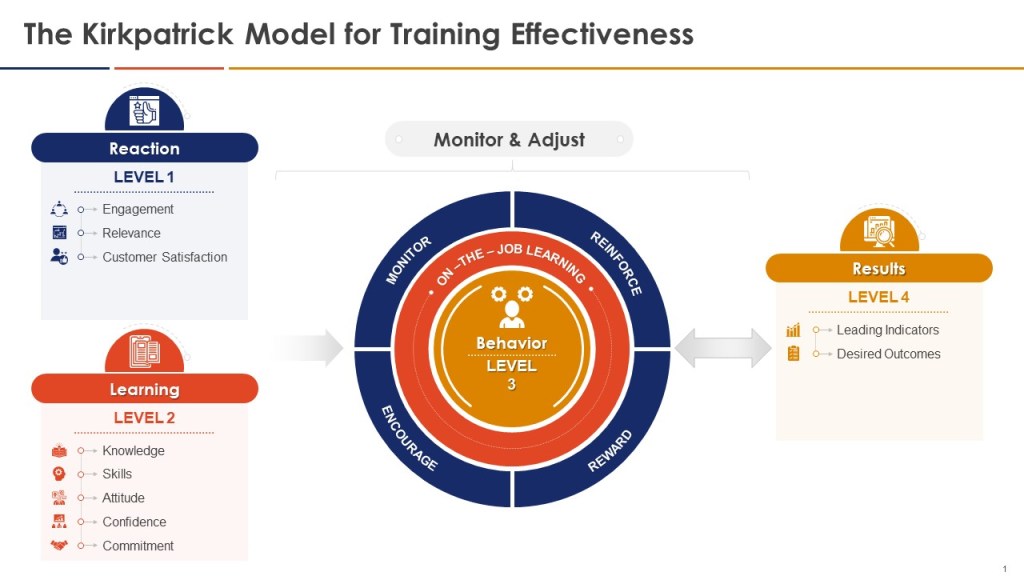

Falsifiable training systems require sophisticated measurement approaches that can detect both positive outcomes and training failures. Traditional training evaluation often relies on Kirkpatrick’s four-level model—reaction, learning, behavior, and results—but applies it in ways that confirm rather than challenge training effectiveness. Falsifiable systems use the Kirkpatrick framework as a starting point but enhance it with rigorous hypothesis testing approaches that can identify training failures as clearly as training successes.

Level 1 (Reaction) measurements in falsifiable systems focus on engagement indicators that predict subsequent learning rather than generic satisfaction scores. These might include the quality of questions asked during training sessions, the depth of participation in case study discussions, or the specificity of action plans developed by participants. Rather than measuring whether participants “liked” the training, falsifiable systems measure whether participants demonstrated the type of engagement that research shows correlates with subsequent performance improvement.

Level 2 (Learning) measurements employ pre- and post-training assessments designed to detect specific knowledge and skill development rather than general awareness. These assessments use scenario-based questions that require application of training content to realistic work situations, ensuring that learning measurement reflects practical competence rather than theoretical knowledge. Critically, falsifiable systems include “distractor” assessments that test knowledge not covered in training, helping to distinguish genuine learning from test-taking artifacts or regression to the mean effects.

Level 3 (Behavior) measurements represent the most challenging aspect of falsifiable training evaluation, requiring observation and documentation of actual workplace behavior change. Effective approaches include structured observation protocols, 360-degree feedback systems focused on specific behaviors taught in training, and analysis of work products for evidence of skill application. For example, CAPA training effectiveness might be measured by evaluating investigation reports before and after training using standardized rubrics that assess analytical depth, evidence quality, and causal reasoning.

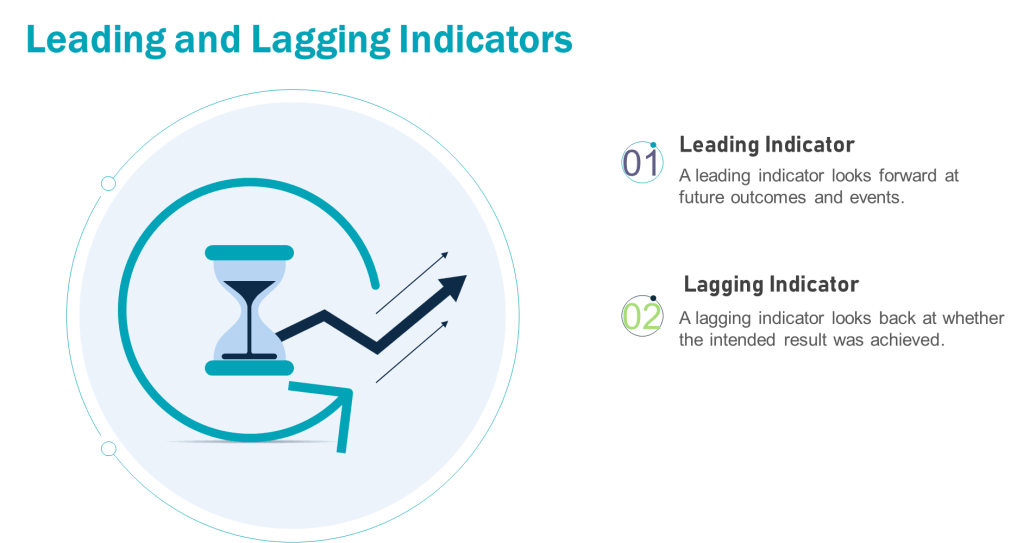

Level 4 (Results) measurements in falsifiable systems focus on leading indicators that can provide early evidence of training impact rather than waiting for lagging indicators like deviation rates or audit performance. These might include measures of proactive risk identification, voluntary improvement suggestions, or peer-to-peer knowledge transfer. The key is selecting results measures that are closely linked to the specific behaviors and competencies developed through training while being sensitive enough to detect changes within reasonable time frames.

Risk-Based Training Design and Implementation

The integration of Quality Risk Management (QRM) principles with training design represents a fundamental advancement in pharmaceutical education methodology. Rather than developing generic training programs based on regulatory requirements or industry best practices, risk-based training design begins with systematic analysis of the specific risks posed by knowledge and skill gaps within the organization. This approach aligns training investments with actual quality and compliance risks while ensuring that educational resources address the most critical performance needs.

Risk-based training design employs the ICH Q9(R1) framework to systematically identify, assess, and mitigate training-related risks throughout the pharmaceutical quality system. Risk identification focuses on understanding how knowledge and skill deficiencies could impact product quality, patient safety, or regulatory compliance. For example, inadequate understanding of aseptic technique among sterile manufacturing personnel represents a high-impact risk with direct patient safety implications, while superficial knowledge of change control procedures might create lower-magnitude but higher-frequency compliance risks.

The risk assessment phase quantifies both the probability and impact of training-related failures while considering existing controls and mitigation measures. This analysis helps prioritize training investments and design appropriate learning interventions. High-risk knowledge gaps require intensive, hands-on training with multiple assessment checkpoints and ongoing competency verification. Lower-risk areas might be addressed through self-paced learning modules or periodic refresher training. The risk assessment also identifies scenarios where training alone is insufficient, requiring procedural changes, system enhancements, or additional controls to adequately manage identified risks.

Proactive Risk Detection Through Learning Analytics

Advanced risk-based training systems employ learning analytics to identify emerging competency risks before they manifest as quality failures or compliance violations. These systems continuously monitor training effectiveness indicators, looking for patterns that suggest degrading competence or emerging knowledge gaps. For example, declining assessment scores across multiple personnel might indicate inadequate training design, while individual performance variations could suggest the need for personalized learning interventions.

Learning analytics in pharmaceutical training systems must be designed to respect privacy while providing actionable insights for quality management. Effective approaches include aggregate trend analysis that identifies systemic issues without exposing individual performance, predictive modeling that forecasts training needs based on operational changes, and comparative analysis that benchmarks training effectiveness across different sites or product lines. These analytics support proactive quality management by enabling early intervention before competency gaps impact operations.

The integration of learning analytics with quality management systems creates powerful opportunities for continuous improvement in both training effectiveness and operational performance. By correlating training metrics with quality outcomes, organizations can identify which aspects of their training programs drive the greatest performance improvements and allocate resources accordingly. This data-driven approach transforms training from a compliance activity into a strategic quality management tool that actively contributes to organizational excellence.

Risk Communication and Training Transfer

Risk-based training design recognizes that effective learning transfer requires personnel to understand not only what to do but why it matters from a risk management perspective. Training programs that explicitly connect learning objectives to quality risks and patient safety outcomes demonstrate significantly higher retention and application rates than programs focused solely on procedural compliance. This approach leverages the psychological principle of meaningful learning, where understanding the purpose and consequences of actions enhances both motivation and performance.

Effective risk communication in training contexts requires careful balance between creating appropriate concern about potential consequences while maintaining confidence and motivation. Training programs should help personnel understand how their individual actions contribute to broader quality objectives and patient safety outcomes without creating paralyzing anxiety about potential failures. This balance is achieved through specific, actionable guidance that empowers personnel to make appropriate decisions while understanding the risk implications of their choices.

The development of risk communication competencies represents a critical training need across pharmaceutical organizations. Personnel at all levels must be able to identify, assess, and communicate about quality risks in ways that enable appropriate decision-making and continuous improvement. This includes technical skills like hazard identification and risk assessment as well as communication skills that enable effective knowledge transfer, problem escalation, and collaborative problem-solving. Training programs that develop these meta-competencies create multiplicative effects that enhance overall organizational capability beyond the specific technical content being taught.

Building Quality Maturity Through Structured Learning

The FDA’s Quality Management Maturity (QMM) program provides a framework for understanding how training contributes to overall organizational excellence in pharmaceutical manufacturing. QMM assessment examines five key areas—management commitment to quality, business continuity, advanced pharmaceutical quality system, technical excellence, and employee engagement and empowerment—with training playing critical roles in each area. Mature organizations demonstrate systematic approaches to developing and maintaining competencies that support these quality management dimensions.

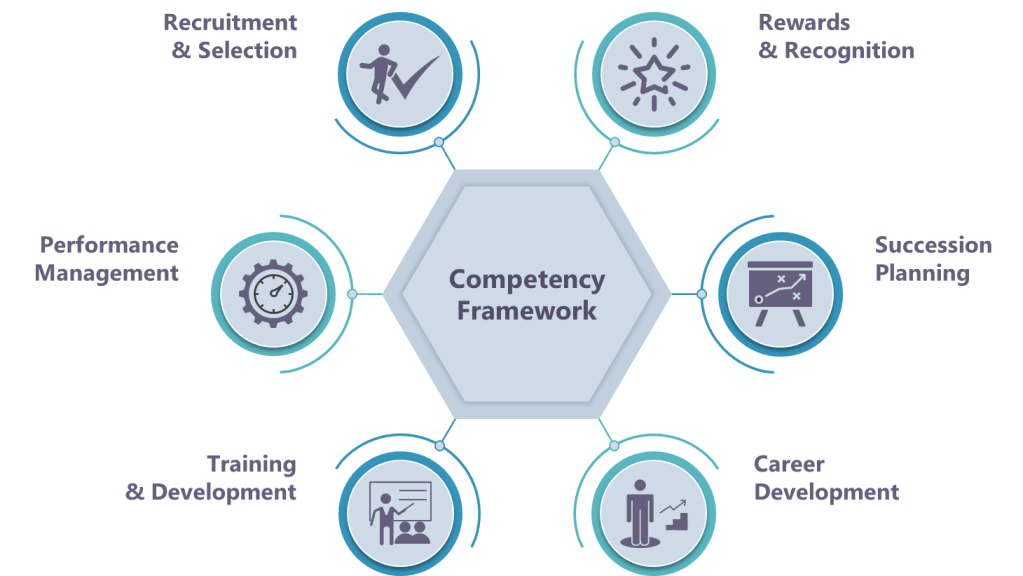

Quality maturity in training systems manifests through several observable characteristics: systematic competency modeling that defines required knowledge, skills, and behaviors for each role; evidence-based training design that uses adult learning principles and performance improvement methodologies; comprehensive measurement systems that track training effectiveness across multiple dimensions; and continuous improvement processes that refine training based on performance outcomes and organizational feedback. These characteristics distinguish mature training systems from compliance-focused programs that meet regulatory requirements without driving performance improvement.

The development of quality maturity requires organizations to move beyond reactive training approaches that respond to identified deficiencies toward proactive systems that anticipate future competency needs and prepare personnel for evolving responsibilities. This transition involves sophisticated workforce planning, competency forecasting, and strategic learning design that aligns with broader organizational objectives. Mature organizations treat training as a strategic capability that enables business success rather than a cost center that consumes resources for compliance purposes.

Competency-Based Learning Architecture

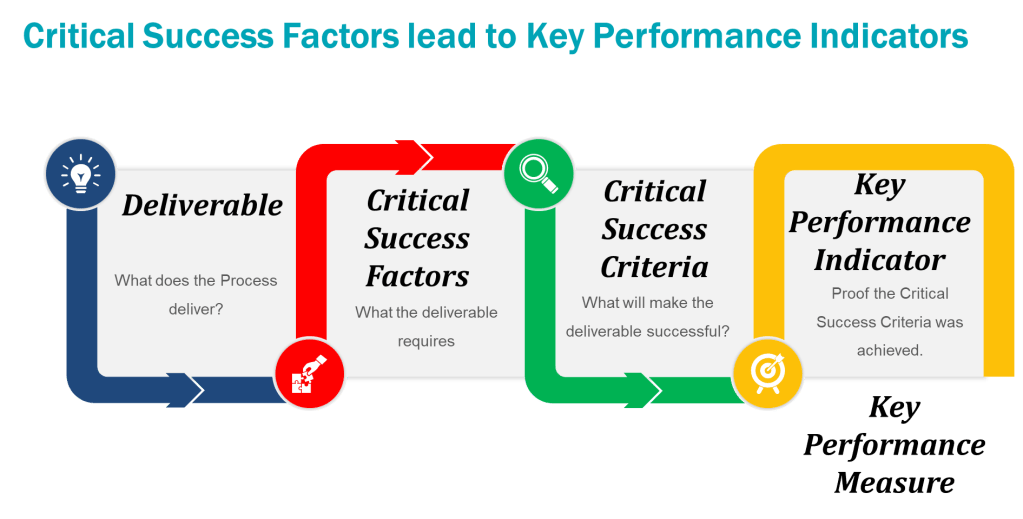

Competency-based training design represents a fundamental departure from traditional knowledge-transfer approaches, focusing instead on the specific behaviors and performance outcomes that drive quality excellence. This approach begins with detailed job analysis and competency modeling that identifies the critical success factors for each role within the pharmaceutical quality system. For example, a competency model for quality assurance personnel might specify technical competencies like analytical problem-solving and regulatory knowledge alongside behavioral competencies like attention to detail and collaborative communication.

The architecture of competency-based learning systems includes several interconnected components: competency frameworks that define performance standards for each role; assessment strategies that measure actual competence rather than theoretical knowledge; learning pathways that develop competencies through progressive skill building; and performance support systems that reinforce learning in the workplace. These components work together to create comprehensive learning ecosystems that support both initial competency development and ongoing performance improvement.

Competency-based systems also incorporate adaptive learning technologies that personalize training based on individual performance and learning needs. Advanced systems use diagnostic assessments to identify specific competency gaps and recommend targeted learning interventions. This personalization increases training efficiency while ensuring that all personnel achieve required competency levels regardless of their starting point or learning preferences. The result is more effective training that requires less time and resources while achieving superior performance outcomes.

Progressive Skill Development Models

Quality maturity requires training systems that support continuous competency development throughout personnel careers rather than one-time certification approaches. Progressive skill development models provide structured pathways for advancing from basic competence to expert performance, incorporating both formal training and experiential learning opportunities. These models recognize that expertise development is a long-term process requiring sustained practice, feedback, and reflection rather than short-term information transfer.

Effective progressive development models incorporate several design principles: clear competency progression pathways that define advancement criteria; diverse learning modalities that accommodate different learning preferences and situations; mentorship and coaching components that provide personalized guidance; and authentic assessment approaches that evaluate real-world performance rather than abstract knowledge. For example, a progression pathway for CAPA investigators might begin with fundamental training in problem-solving methodologies, advance through guided practice on actual investigations, and culminate in independent handling of complex quality issues with peer review and feedback.

The implementation of progressive skill development requires sophisticated tracking systems that monitor individual competency development over time and identify opportunities for advancement or intervention. These systems must balance standardization—ensuring consistent competency development across the organization—with flexibility that accommodates individual differences in learning pace and career objectives. Successful systems also incorporate recognition and reward mechanisms that motivate continued competency development and reinforce the organization’s commitment to learning excellence.

Practical Implementation Framework

Systematic Training Needs Analysis

The foundation of effective training in pharmaceutical quality systems requires systematic needs analysis that moves beyond compliance-driven course catalogs to identify actual performance gaps and learning opportunities. This analysis employs multiple data sources—including deviation analyses, audit findings, near-miss reports, and performance metrics—to understand where training can most effectively contribute to quality improvement. Rather than assuming that all personnel need the same training, systematic needs analysis identifies specific competency requirements for different roles, experience levels, and operational contexts.

Effective needs analysis in pharmaceutical environments must account for the complex interdependencies within quality systems, recognizing that individual performance occurs within organizational systems that can either support or undermine training effectiveness. This systems perspective examines how organizational factors like procedures, technology, supervision, and incentives influence training transfer and identifies barriers that must be addressed for training to achieve its intended outcomes. For example, excellent CAPA training may fail to improve investigation quality if organizational systems continue to prioritize speed over thoroughness or if personnel lack access to necessary analytical tools.

The integration of predictive analytics into training needs analysis enables organizations to anticipate future competency requirements based on operational changes, regulatory developments, or quality system evolution. This forward-looking approach prevents competency gaps from developing rather than reacting to them after they impact performance. Predictive needs analysis might identify emerging training requirements related to new manufacturing technologies, evolving regulatory expectations, or changing product portfolios, enabling proactive competency development that maintains quality system effectiveness during periods of change.

Development of Falsifiable Learning Objectives

Traditional training programs often employ learning objectives that are inherently unfalsifiable—statements like “participants will understand good documentation practices” or “attendees will appreciate the importance of quality” that cannot be tested or proven wrong. Falsifiable learning objectives, by contrast, specify precise, observable, and measurable outcomes that can be independently verified. For example, a falsifiable objective might state: “Following training, participants will identify 90% of documentation deficiencies in standardized case studies and propose appropriate corrective actions that address root causes rather than symptoms.”

The development of falsifiable learning objectives requires careful consideration of the relationship between training content and desired performance outcomes. Objectives must be specific enough to enable rigorous testing while remaining meaningful for actual job performance. This balance requires deep understanding of both the learning content and the performance context, ensuring that training objectives align with real-world quality requirements. Effective falsifiable objectives specify not only what participants will know but how they will apply that knowledge in specific situations with measurable outcomes.

Falsifiable learning objectives also incorporate temporal specificity, defining when and under what conditions the specified outcomes should be observable. This temporal dimension enables systematic follow-up assessment that can verify whether training has achieved its intended effects. For example, an objective might specify that participants will demonstrate improved investigation techniques within 30 days of training completion, as measured by structured evaluation of actual investigation reports using standardized assessment criteria. This specificity enables organizations to identify training successes and failures with precision, supporting continuous improvement in educational effectiveness.

Assessment Design for Performance Verification

The assessment of training effectiveness in falsifiable quality systems requires sophisticated evaluation methods that can distinguish between superficial compliance and genuine competency development. Traditional assessment approaches—multiple-choice tests, attendance tracking, and satisfaction surveys—provide limited insight into actual performance capability and cannot support rigorous testing of training hypotheses. Falsifiable assessment systems employ authentic evaluation methods that measure performance in realistic contexts using criteria that reflect actual job requirements.

Scenario-based assessment represents one of the most effective approaches for evaluating competency in pharmaceutical quality contexts. These assessments present participants with realistic quality challenges that require application of training content to novel situations, providing insight into both knowledge retention and problem-solving capability. For example, CAPA training assessment might involve analyzing actual case studies of quality failures, requiring participants to identify root causes, develop corrective actions, and design preventive measures that address underlying system weaknesses. The quality of these responses can be evaluated using structured rubrics that provide objective measures of competency development.

Performance-based assessment extends evaluation beyond individual knowledge to examine actual workplace behavior and outcomes. This approach requires collaboration between training and operational personnel to design assessment methods that capture authentic job performance while providing actionable feedback for improvement. Performance-based assessment might include structured observation of personnel during routine activities, evaluation of work products using quality criteria, or analysis of performance metrics before and after training interventions. The key is ensuring that assessment methods provide valid measures of the competencies that training is intended to develop.

Continuous Improvement and Adaptation

Falsifiable training systems require robust mechanisms for continuous improvement based on empirical evidence of training effectiveness. This improvement process goes beyond traditional course evaluations to examine actual training outcomes against predicted results, identifying specific aspects of training design that contribute to success or failure. Continuous improvement in falsifiable systems is driven by data rather than opinion, using systematic analysis of training metrics to refine educational approaches and enhance performance outcomes.

The continuous improvement process must examine training effectiveness at multiple levels—individual learning, operational performance, and organizational outcomes—to identify optimization opportunities across the entire training system. Individual-level analysis might reveal specific content areas where learners consistently struggle, suggesting the need for enhanced instructional design or additional practice opportunities. Operational-level analysis might identify differences in training effectiveness across different sites or departments, indicating the need for contextual adaptation or implementation support. Organizational-level analysis might reveal broader patterns in training impact that suggest strategic changes in approach or resource allocation.

Continuous improvement also requires systematic experimentation with new training approaches, using controlled trials and pilot programs to test innovations before full implementation. This experimental approach enables organizations to stay current with advances in adult learning while maintaining evidence-based decision making about educational investments. For example, an organization might pilot virtual reality training for aseptic technique while continuing traditional approaches, comparing outcomes to determine which method produces superior performance improvement. This experimental mindset transforms training from a static compliance function into a dynamic capability that continuously evolves to meet organizational needs.

An Example

| Competency | Assessment Type | Falsifiable Hypothesis | Assessment Method | Success Criteria | Failure Criteria (Falsification) |

| Gowning Procedures | Level 1: Reaction | Trainees will rate gowning training as ≥4.0/5.0 for relevance and engagement | Post-training survey with Likert scale ratings | Mean score ≥4.0 with <10% of responses below 3.0 | Mean score <4.0 OR >10% responses below 3.0 |

| Gowning Procedures | Level 2: Learning | Trainees will demonstrate 100% correct gowning sequence in post-training assessment | Written exam + hands-on gowning demonstration with checklist | 100% pass rate on practical demonstration within 2 attempts | <100% pass rate after 2 attempts OR critical safety errors observed |

| Gowning Procedures | Level 3: Behavior | Operators will maintain <2% gowning deviations during observed cleanroom entries over 30 days | Direct observation with standardized checklist over multiple shifts | Statistical significance (p<0.05) in deviation reduction vs. baseline | No statistically significant improvement OR increase in deviations |

| Gowning Procedures | Level 4: Results | Gowning-related contamination events will decrease by ≥50% within 90 days post-training | Trend analysis of contamination event data with statistical significance testing | 50% reduction confirmed by chi-square analysis (p<0.05) | <50% reduction OR no statistical significance (p≥0.05) |

| Aseptic Technique | Level 1: Reaction | Trainees will rate aseptic technique training as ≥4.2/5.0 for practical applicability | Post-training survey focusing on perceived job relevance and confidence | Mean score ≥4.2 with confidence interval ≥3.8-4.6 | Mean score <4.2 OR confidence interval below 3.8 |

| Aseptic Technique | Level 2: Learning | Trainees will achieve ≥90% on aseptic technique knowledge assessment and skills demonstration | Combination written test and practical skills assessment with video review | 90% first-attempt pass rate with skills assessment score ≥85% | <90% pass rate OR skills assessment score <85% |

| Aseptic Technique | Level 3: Behavior | Operators will demonstrate proper first air protection in ≥95% of observed aseptic manipulations | Real-time observation using behavioral checklist during routine operations | Statistically significant improvement in compliance rate vs. pre-training | No statistically significant behavioral change OR compliance decrease |

| Aseptic Technique | Level 4: Results | Aseptic process simulation failure rates will decrease by ≥40% within 6 months | APS failure rate analysis with control group comparison and statistical testing | 40% reduction in APS failures with 95% confidence interval | <40% APS failure reduction OR confidence interval includes zero |

| Environmental Monitoring | Level 1: Reaction | Trainees will rate EM training as ≥4.0/5.0 for understanding monitoring rationale | Survey measuring comprehension and perceived value of monitoring program | Mean score ≥4.0 with standard deviation <0.8 | Mean score <4.0 OR standard deviation >0.8 indicating inconsistent understanding |

| Environmental Monitoring | Level 2: Learning | Trainees will correctly identify ≥90% of sampling locations and techniques in practical exam | Practical examination requiring identification and demonstration of techniques | 90% pass rate on location identification and 95% on technique demonstration | <90% location accuracy OR <95% technique demonstration success |

| Environmental Monitoring | Level 3: Behavior | Personnel will perform EM sampling with <5% procedural deviations during routine operations | Audit-style observation with deviation tracking and root cause analysis | Significant reduction in deviation rate compared to historical baseline | No significant reduction in deviations OR increase above baseline |

| Environmental Monitoring | Level 4: Results | Lab Error EM results will decrease by ≥30% within 120 days of training completion | Statistical analysis of EM excursion trends with pre/post training comparison | 30% reduction in lab error rate with statistical significance and sustained trend | <30% lab error reduction OR lack of statistical significance |

| Material Transfer | Level 1: Reaction | Trainees will rate material transfer training as ≥3.8/5.0 for workflow integration understanding | Survey assessing understanding of contamination pathways and prevention | Mean score ≥3.8 with >70% rating training as “highly applicable” | Mean score <3.8 OR <70% rating as applicable |

| Material Transfer | Level 2: Learning | Trainees will demonstrate 100% correct transfer procedures in simulated scenarios | Simulation-based assessment with pass/fail criteria and video documentation | 100% demonstration success with zero critical procedural errors | <100% demonstration success OR any critical procedural errors |

| Material Transfer | Level 3: Behavior | Material transfer protocol violations will be <3% during observed operations over 60 days | Structured observation protocol with immediate feedback and correction | Violation rate <3% sustained over 60-day observation period | Violation rate ≥3% OR inability to sustain improvement |

| Material Transfer | Level 4: Results | Cross-contamination incidents related to material transfer will decrease by ≥60% within 6 months | Incident trend analysis with correlation to training completion dates | 60% incident reduction with 6-month sustained improvement confirmed | <60% incident reduction OR failure to sustain improvement |

| Cleaning & Disinfection | Level 1: Reaction | Trainees will rate cleaning training as ≥4.1/5.0 for understanding contamination risks | Survey measuring risk awareness and procedure confidence levels | Mean score ≥4.1 with >80% reporting increased contamination risk awareness | Mean score <4.1 OR <80% reporting increased risk awareness |

| Cleaning & Disinfection | Level 2: Learning | Trainees will achieve ≥95% accuracy in cleaning agent selection and application method tests | Knowledge test combined with practical application assessment | 95% accuracy rate with no critical knowledge gaps identified | <95% accuracy OR identification of critical knowledge gaps |

| Cleaning & Disinfection | Level 3: Behavior | Cleaning procedure compliance will be ≥98% during direct observation over 45 days | Compliance monitoring with photo/video documentation of techniques | 98% compliance rate maintained across multiple observation cycles | <98% compliance OR declining performance over observation period |

| Cleaning & Disinfection | Level 4: Results | Cleaning-related contamination findings will decrease by ≥45% within 90 days post-training | Contamination event investigation with training correlation analysis | 45% reduction in findings with sustained improvement over 90 days | <45% reduction in findings OR inability to sustain improvement |

Technology Integration and Digital Learning Ecosystems

Learning Management Systems for Quality Applications

The days where the Learning Management Systems (LMS) is just there to track read-and-understands, on-the-job trainings and a few other things should be in the past. Unfortunately few technology providers have risen to the need and struggle to provide true competency tracking aligned with regulatory expectations, and integration with quality management systems. Pharmaceutical-capable LMS solutions must provide comprehensive documentation of training activities while supporting advanced learning analytics that can demonstrate training effectiveness.

We cry out for robust LMS platforms that incorporate sophisticated competency management features that align with quality system requirements while supporting personalized learning experiences. We need systems can track individual competency development over time, identify training needs based on role changes or performance gaps, and automatically schedule required training based on regulatory timelines or organizational policies. Few organizations have the advanced platforms that also support adaptive learning pathways that adjust content and pacing based on individual performance, ensuring that all personnel achieve required competency levels while optimizing training efficiency.

It is critical to have integration of LMS platforms with broader quality management systems to enable the powerful analytics that can correlate training metrics with operational performance indicators. This integration supports data-driven decision making about training investments while providing evidence of training effectiveness for regulatory inspections. For example, integrated systems might demonstrate correlations between enhanced CAPA training and reduced deviation recurrence rates, providing objective evidence that training investments are contributing to quality improvement. This analytical capability transforms training from a cost center into a measurable contributor to organizational performance.

Give me a call LMS/eQMS providers. I’ll gladly provide some consulting hours to make this actually happen.

Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications

We are just starting to realize the opportunities that virtual and augmented reality technologies offer for immersive training experiences that can simulate high-risk scenarios without compromising product quality or safety. These technologies are poised to be particularly valuable for pharmaceutical quality training because they enable realistic practice with complex procedures, equipment, or emergency situations that would be difficult or impossible to replicate in traditional training environments. For example, virtual reality can provide realistic simulation of cleanroom operations, allowing personnel to practice aseptic technique and emergency procedures without risk of contamination or product loss.

The effectiveness of virtual reality training in pharmaceutical applications depends on careful design that maintains scientific accuracy while providing engaging learning experiences. Training simulations must incorporate authentic equipment interfaces, realistic process parameters, and accurate consequences for procedural deviations to ensure that virtual experiences translate to improved real-world performance. Advanced VR training systems also incorporate intelligent tutoring features that provide personalized feedback and guidance based on individual performance, enhancing learning efficiency while maintaining training consistency across organizations.

Augmented reality applications provide complementary capabilities for performance support and just-in-time training delivery. AR systems can overlay digital information onto real-world environments, providing contextual guidance during actual work activities or offering detailed procedural information without requiring personnel to consult separate documentation. For quality applications, AR might provide real-time guidance during equipment qualification procedures, overlay quality specifications during inspection activities, or offer troubleshooting assistance during non-routine situations. These applications bridge the gap between formal training and workplace performance, supporting continuous learning throughout daily operations.

Data Analytics for Learning Optimization

The application of advanced analytics to pharmaceutical training data enables unprecedented insights into learning effectiveness while supporting evidence-based optimization of educational programs. Modern analytics platforms can examine training data across multiple dimensions—individual performance patterns, content effectiveness, temporal dynamics, and correlation with operational outcomes—to identify specific factors that contribute to training success or failure. This analytical capability transforms training from an intuitive art into a data-driven science that can be systematically optimized for maximum performance impact.

Predictive analytics applications can forecast training needs based on operational changes, identify personnel at risk of competency degradation, and recommend personalized learning interventions before performance issues develop. These systems analyze patterns in historical training and performance data to identify early warning indicators of competency gaps, enabling proactive intervention that prevents quality problems rather than reacting to them. For example, predictive models might identify personnel whose performance patterns suggest the need for refresher training before deviation rates increase or audit findings develop.

Learning analytics also enable sophisticated A/B testing of training approaches, allowing organizations to systematically compare different educational methods and identify optimal approaches for specific content areas or learner populations. This experimental capability supports continuous improvement in training design while providing objective evidence of educational effectiveness. For instance, organizations might compare scenario-based learning versus traditional lecture approaches for CAPA training, using performance metrics to determine which method produces superior outcomes for different learner groups. This evidence-based approach ensures that training investments produce maximum returns in terms of quality performance improvement.

Organizational Culture and Change Management

Leadership Development for Quality Excellence

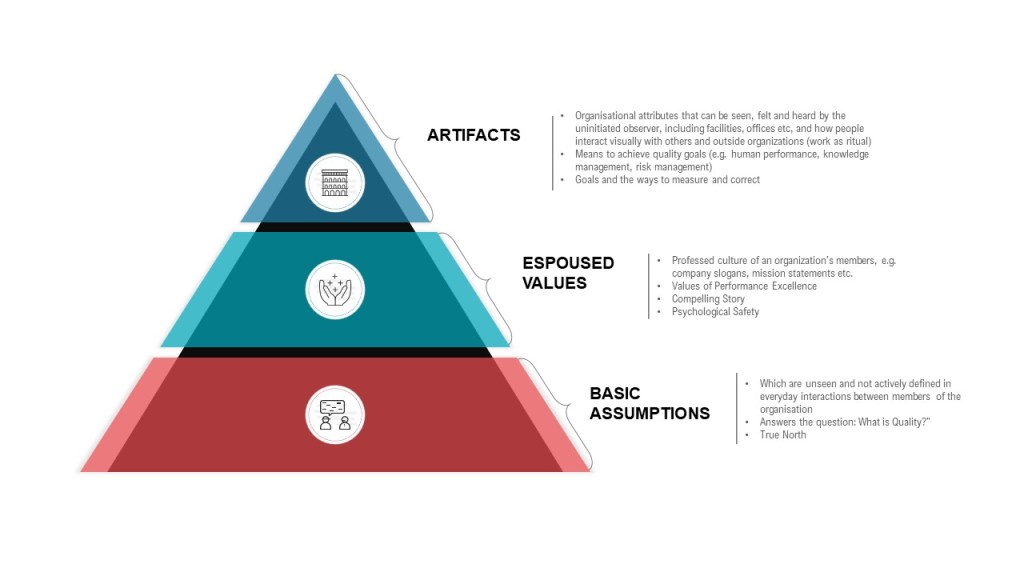

The development of quality leadership capabilities represents a critical component of training systems that aim to build robust quality cultures throughout pharmaceutical organizations. Quality leadership extends beyond technical competence to encompass the skills, behaviors, and mindset necessary to drive continuous improvement, foster learning environments, and maintain unwavering commitment to patient safety and product quality. Training programs for quality leaders must address both the technical aspects of quality management and the human dimensions of leading change, building trust, and creating organizational conditions that support excellent performance.

Effective quality leadership training incorporates principles from both quality science and organizational psychology, helping leaders understand how to create systems that enable excellent performance rather than simply demanding compliance. This approach recognizes that sustainable quality improvement requires changes in organizational culture, systems, and processes rather than exhortations to “do better” or increased oversight. Quality leaders must understand how to design work systems that make good performance easier and poor performance more difficult, while creating cultures that encourage learning from failures and continuous improvement.

The assessment of leadership development effectiveness requires sophisticated measurement approaches that examine both individual competency development and organizational outcomes. Traditional leadership training evaluation often focuses on participant reactions or knowledge acquisition rather than behavioral change and organizational impact. Quality leadership assessment must examine actual leadership behaviors in workplace contexts, measure changes in organizational climate and culture indicators, and correlate leadership development with quality performance improvements. This comprehensive assessment approach ensures that leadership training investments produce tangible improvements in organizational quality capability.

Creating Learning Organizations

The transformation of pharmaceutical organizations into learning organizations requires systematic changes in culture, processes, and systems that go beyond individual training programs to address how knowledge is created, shared, and applied throughout the organization. Learning organizations are characterized by their ability to continuously improve performance through systematic learning from both successes and failures, adapting to changing conditions while maintaining core quality commitments. This transformation requires coordinated changes in organizational design, management practices, and individual capabilities that support collective learning and continuous improvement.

The development of learning organization capabilities requires specific attention to psychological safety, knowledge management systems, and improvement processes that enable organizational learning. Psychological safety—the belief that one can speak up, ask questions, or admit mistakes without fear of negative consequences—represents a fundamental prerequisite for organizational learning in regulated industries where errors can have serious consequences. Training programs must address both the technical aspects of creating psychological safety and the practical skills necessary for effective knowledge sharing, constructive challenge, and collaborative problem-solving.

Knowledge management systems in learning organizations must support both explicit knowledge transfer—through documentation, training programs, and formal communication systems—and tacit knowledge sharing through mentoring, communities of practice, and collaborative work arrangements. These systems must also incorporate mechanisms for capturing and sharing lessons learned from quality events, process improvements, and regulatory interactions to ensure that organizational learning extends beyond individual experiences. Effective knowledge management requires both technological platforms and social processes that encourage knowledge sharing and application.

Sustaining Behavioral Change

The sustainability of behavioral change following training interventions represents one of the most significant challenges in pharmaceutical quality education. Research consistently demonstrates that without systematic reinforcement and support systems, training-induced behavior changes typically decay within weeks or months of training completion. Sustainable behavior change requires comprehensive support systems that reinforce new behaviors, provide ongoing skill development opportunities, and maintain motivation for continued improvement beyond the initial training period.

Effective behavior change sustainability requires systematic attention to both individual and organizational factors that influence performance maintenance. Individual factors include skill consolidation through practice and feedback, motivation maintenance through goal setting and recognition, and habit formation through consistent application of new behaviors. Organizational factors include system changes that make new behaviors easier to perform, management support that reinforces desired behaviors, and measurement systems that track and reward behavior change outcomes.

The design of sustainable training systems must incorporate multiple reinforcement mechanisms that operate across different time horizons to maintain behavior change momentum. Immediate reinforcement might include feedback systems that provide real-time performance information. Short-term reinforcement might involve peer recognition programs or supervisor coaching sessions. Long-term reinforcement might include career development opportunities that reward sustained performance improvement or organizational recognition programs that celebrate quality excellence achievements. This multi-layered approach ensures that new behaviors become integrated into routine performance patterns rather than remaining temporary modifications that decay over time.

Regulatory Alignment and Global Harmonization

FDA Quality Management Maturity Integration

The FDA’s Quality Management Maturity program provides a strategic framework for aligning training investments with regulatory expectations while driving organizational excellence beyond basic compliance requirements. The QMM program emphasizes five key areas where training plays critical roles: management commitment to quality, business continuity, advanced pharmaceutical quality systems, technical excellence, and employee engagement and empowerment. Training programs aligned with QMM principles demonstrate systematic approaches to competency development that support mature quality management practices rather than reactive compliance activities.

Integration with FDA QMM requirements necessitates training systems that can demonstrate measurable contributions to quality management maturity across multiple organizational dimensions. This demonstration requires sophisticated metrics that show how training investments translate into improved quality outcomes, enhanced organizational capabilities, and greater resilience in the face of operational challenges. Training programs must be able to document their contributions to predictive quality management, proactive risk identification, and continuous improvement processes that characterize mature pharmaceutical quality systems.

The alignment of training programs with QMM principles also requires ongoing adaptation as the program evolves and regulatory expectations mature. Organizations must maintain awareness of emerging FDA guidance, industry best practices, and international harmonization efforts that influence quality management expectations. This adaptability requires training systems with sufficient flexibility to incorporate new requirements while maintaining focus on fundamental quality competencies that remain constant across regulatory changes. The result is training programs that support both current compliance and future regulatory evolution.

International Harmonization Considerations

The global nature of pharmaceutical manufacturing requires training systems that can support consistent quality standards across different regulatory jurisdictions while accommodating regional variations in regulatory expectations and cultural contexts. International harmonization efforts, particularly through ICH guidelines like Q9(R1), Q10, and Q12, provide frameworks for developing training programs that meet global regulatory expectations while supporting business efficiency through standardized approaches.

Harmonized training approaches must balance standardization—ensuring consistent quality competencies across global operations—with localization that addresses specific regulatory requirements, cultural factors, and operational contexts in different regions. This balance requires sophisticated training design that identifies core competencies that remain constant across jurisdictions while providing flexible modules that address regional variations. For example, core quality management competencies might be standardized globally while specific regulatory reporting requirements are tailored to regional needs.

The implementation of harmonized training systems requires careful attention to cultural differences in learning preferences, communication styles, and organizational structures that can influence training effectiveness across different regions. Effective global training programs incorporate cultural intelligence into their design, using locally appropriate learning methodologies while maintaining consistent learning outcomes. This cultural adaptation ensures that training effectiveness is maintained across diverse global operations while supporting the development of shared quality culture that transcends regional boundaries.

Emerging Regulatory Trends

The pharmaceutical regulatory landscape continues to evolve toward greater emphasis on quality system effectiveness rather than procedural compliance, requiring training programs that can adapt to emerging regulatory expectations while maintaining focus on fundamental quality principles. Recent regulatory developments, including the draft revision of EU GMP Chapter 1 and evolving FDA enforcement priorities, emphasize knowledge management, risk-based decision making, and continuous improvement as core quality system capabilities that must be supported through comprehensive training programs.

Emerging regulatory trends also emphasize the importance of data integrity, cybersecurity, and supply chain resilience as critical quality competencies that require specialized training development. These evolving requirements necessitate training systems that can rapidly incorporate new content areas while maintaining the depth and rigor necessary for effective competency development. Organizations must develop training capabilities that can anticipate regulatory evolution rather than merely reacting to new requirements after they are published.

The integration of advanced technologies—including artificial intelligence, machine learning, and advanced analytics—into pharmaceutical manufacturing creates new training requirements for personnel who must understand both the capabilities and limitations of these technologies. Training programs must prepare personnel to work effectively with intelligent systems while maintaining the critical thinking and decision-making capabilities necessary for quality oversight. This technology integration represents both an opportunity for enhanced training effectiveness and a requirement for new competency development that supports technological advancement while preserving quality excellence.

Measuring Return on Investment and Business Value

Financial Metrics for Training Effectiveness

The demonstration of training program value in pharmaceutical organizations requires sophisticated financial analysis that can quantify both direct cost savings and indirect value creation resulting from improved competency. Traditional training ROI calculations often focus on obvious metrics like reduced deviation rates or decreased audit findings while missing broader value creation through improved productivity, enhanced innovation capability, and increased organizational resilience. Comprehensive financial analysis must capture the full spectrum of training benefits while accounting for the long-term nature of competency development and performance improvement.

Direct financial benefits of effective training include quantifiable improvements in quality metrics that translate to cost savings: reduced product losses due to quality failures, decreased regulatory remediation costs, improved first-time approval rates for new products, and reduced costs associated with investigations and corrective actions. These benefits can be measured using standard financial analysis methods, comparing operational costs before and after training interventions while controlling for other variables that might influence performance. For example, enhanced CAPA training might be evaluated based on reductions in recurring deviations, decreased investigation cycle times, and improved effectiveness of corrective actions.

Indirect financial benefits require more sophisticated analysis but often represent the largest component of training value creation. These benefits include improved employee engagement and retention, enhanced organizational reputation and regulatory standing, increased capability for innovation and continuous improvement, and greater operational flexibility and resilience. The quantification of these benefits requires advanced analytical methods that can isolate training contributions from other organizational influences while providing credible estimates of economic value. This analysis must also consider the temporal dynamics of training benefits, which often increase over time as competencies mature and organizational capabilities develop.

Quality Performance Indicators

The development of quality performance indicators that can demonstrate training effectiveness requires careful selection of metrics that reflect both training outcomes and broader organizational performance. These indicators must be sensitive enough to detect training impacts while being specific enough to attribute improvements to educational interventions rather than other organizational changes. Effective quality performance indicators span multiple time horizons and organizational levels, providing comprehensive insight into how training contributes to quality excellence across different dimensions and timeframes.

Leading quality performance indicators focus on early evidence of training impact that can be detected before changes appear in traditional quality metrics. These might include improvements in risk identification rates, increases in voluntary improvement suggestions, enhanced quality of investigation reports, or better performance during training assessments and competency evaluations. Leading indicators enable early detection of training effectiveness while providing opportunities for course correction if training programs are not producing expected outcomes.

Lagging quality performance indicators examine longer-term training impacts on organizational quality outcomes. These indicators include traditional metrics like deviation rates, audit performance, regulatory inspection outcomes, and customer satisfaction measures, but analyzed in ways that can isolate training contributions. Sophisticated analysis techniques, including statistical control methods and comparative analysis across similar facilities or time periods, help distinguish training effects from other influences on quality performance. The integration of leading and lagging indicators provides comprehensive evidence of training value while supporting continuous improvement in educational effectiveness.

Long-term Organizational Benefits

The assessment of long-term organizational benefits from training investments requires longitudinal analysis that can track training impacts over extended periods while accounting for the cumulative effects of sustained competency development. Long-term benefits often represent the most significant value creation from training programs but are also the most difficult to measure and attribute due to the complex interactions between training, organizational development, and environmental changes that occur over extended timeframes.

Organizational capability development represents one of the most important long-term benefits of effective training programs. This development manifests as increased organizational learning capacity, enhanced ability to adapt to regulatory or market changes, improved innovation and problem-solving capabilities, and greater resilience in the face of operational challenges. The measurement of capability development requires assessment methods that examine organizational responses to challenges over time, comparing performance patterns before and after training interventions while considering external factors that might influence organizational capability.

Cultural transformation represents another critical long-term benefit that emerges from sustained training investments in quality excellence. This transformation manifests as increased employee engagement with quality objectives, greater willingness to identify and address quality concerns, enhanced collaboration across organizational boundaries, and stronger commitment to continuous improvement. Cultural assessment requires sophisticated measurement approaches that can detect changes in attitudes, behaviors, and organizational climate over extended periods while distinguishing training influences from other cultural change initiatives.

Transforming Quality Through Educational Excellence

The transformation of pharmaceutical training from compliance-focused information transfer to falsifiable quality system development represents both an urgent necessity and an unprecedented opportunity. The recurring patterns in 2025 FDA warning letters demonstrate that traditional training approaches are fundamentally inadequate for building robust quality systems capable of preventing the failures that continue to plague the pharmaceutical industry. Organizations that continue to rely on training theater—elaborate documentation systems that create the appearance of comprehensive education while failing to drive actual performance improvement—will find themselves increasingly vulnerable to regulatory enforcement and quality failures that compromise patient safety and business sustainability.

The falsifiable quality systems approach offers a scientifically rigorous alternative that transforms training from an unverifiable compliance activity into a testable hypothesis about organizational performance. By developing training programs that generate specific, measurable predictions about learning outcomes and performance improvements, organizations can create educational systems that drive continuous improvement while providing objective evidence of effectiveness. This approach aligns training investments with actual quality outcomes while supporting the development of quality management maturity that meets evolving regulatory expectations and business requirements.

The integration of risk management principles into training design ensures that educational investments address the most critical competency gaps while supporting proactive quality management approaches. Rather than generic training programs based on regulatory checklists, risk-based training design identifies specific knowledge and skill deficiencies that could impact product quality or patient safety, enabling targeted interventions that provide maximum return on educational investment. This risk-based approach transforms training from a reactive compliance function into a proactive quality management tool that prevents problems rather than responding to them after they occur.

The development of quality management maturity through structured learning requires sophisticated competency development systems that support continuous improvement in individual capability and organizational performance. Progressive skill development models provide pathways for advancing from basic compliance to expert performance while incorporating both formal training and experiential learning opportunities. These systems recognize that quality excellence is achieved through sustained competency development rather than one-time certification, requiring comprehensive support systems that maintain performance improvement over extended periods.

The practical implementation of these advanced training approaches requires systematic change management that addresses organizational culture, leadership development, and support systems necessary for educational transformation. Organizations must move beyond viewing training as a cost center that consumes resources for compliance purposes toward recognizing training as a strategic capability that enables business success and quality excellence. This transformation requires leadership commitment, resource allocation, and cultural changes that support continuous learning and improvement throughout the organization.

The measurement of training effectiveness in falsifiable quality systems demands sophisticated assessment approaches that can demonstrate both individual competency development and organizational performance improvement. Traditional training evaluation methods—attendance tracking, completion rates, and satisfaction surveys—provide insufficient insight into actual training impact and cannot support evidence-based improvement in educational effectiveness. Advanced assessment systems must examine training outcomes across multiple dimensions and time horizons while providing actionable feedback for continuous improvement.

The technological enablers available for pharmaceutical training continue to evolve rapidly, offering unprecedented opportunities for immersive learning experiences, personalized education delivery, and sophisticated performance analytics. Organizations that effectively integrate these technologies with sound educational principles can achieve training effectiveness and efficiency improvements that were impossible with traditional approaches. However, technology integration must be guided by learning science and quality management principles rather than technological novelty, ensuring that innovations actually improve educational outcomes rather than merely modernizing ineffective approaches.

The global nature of pharmaceutical manufacturing requires training approaches that can support consistent quality standards across diverse regulatory, cultural, and operational contexts while leveraging local expertise and knowledge. International harmonization efforts provide frameworks for developing training programs that meet global regulatory expectations while supporting business efficiency through standardized approaches. However, harmonization must balance standardization with localization to ensure training effectiveness across different cultural and operational contexts.

The financial justification for advanced training approaches requires comprehensive analysis that captures both direct cost savings and indirect value creation resulting from improved competency. Organizations must develop sophisticated measurement systems that can quantify the full spectrum of training benefits while accounting for the long-term nature of competency development and performance improvement. This financial analysis must consider the cumulative effects of sustained training investments while providing evidence of value creation that supports continued investment in educational excellence.

The future of pharmaceutical quality training lies in the development of learning organizations that can continuously adapt to evolving regulatory requirements, technological advances, and business challenges while maintaining unwavering commitment to patient safety and product quality. These organizations will be characterized by their ability to learn from both successes and failures, share knowledge effectively across organizational boundaries, and maintain cultures that support continuous improvement and innovation. The transformation to learning organization status requires sustained commitment to educational excellence that goes beyond compliance to embrace training as a fundamental capability for organizational success.

The opportunity before pharmaceutical organizations is clear: transform training from a compliance burden into a competitive advantage that drives quality excellence, regulatory success, and business performance. Organizations that embrace falsifiable quality systems, risk-based training design, and quality maturity development will establish sustainable competitive advantages while contributing to the broader pharmaceutical industry’s evolution toward scientific excellence and patient focus. The choice is not whether to improve training effectiveness—the regulatory environment and business pressures make this improvement inevitable—but whether to lead this transformation or be compelled to follow by regulatory enforcement and competitive disadvantage.

The path forward requires courage to abandon comfortable but ineffective traditional approaches in favor of evidence-based training systems that can be rigorously tested and continuously improved. It requires investment in sophisticated measurement systems, advanced technologies, and comprehensive change management that supports organizational transformation. Most importantly, it requires recognition that training excellence is not a destination but a continuous journey toward quality management maturity that serves the fundamental purpose of pharmaceutical manufacturing: delivering safe, effective medicines to patients who depend on our commitment to excellence.

The transformation begins with a single step: the commitment to make training effectiveness falsifiable, measurable, and continuously improvable. Organizations that take this step will discover that excellent training is not an expense to be minimized but an investment that generates compounding returns in quality performance, regulatory success, and organizational capability. The question is not whether this transformation will occur—the regulatory and competitive pressures make it inevitable—but which organizations will lead this change and which will be forced to follow. The choice, and the opportunity, is ours.