The Hidden Architecture of Risk Assessment Failure

Peter Baker‘s blunt assessment, “We allowed all these players into the market who never should have been there in the first place, ” hits at something we all recognize but rarely talk about openly. Here’s the uncomfortable truth: even seasoned quality professionals with decades of experience and proven methodologies can miss critical risks that seem obvious in hindsight. Recognizing this truth is not about competence or dedication. It is about acknowledging that our expertise, no matter how extensive, operates within cognitive frameworks that can create blind spots. The real opportunity lies in understanding how these mental patterns shape our decisions and building knowledge systems that help us see what we might otherwise miss. When we’re honest about these limitations, we can strengthen our approaches and create more robust quality systems.

The framework of risk management, designed to help avoid the monsters of bad decision-making, can all too often fail us. Luckily, the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) guidance document PI 038-2 “Assessment of Quality Risk Management Implementation” identifies three critical observations that reveal systematic vulnerabilities in risk management practice: unjustified assumptions, incomplete identification of risks or inadequate information, and lack of relevant experience with inappropriate use of risk assessment tools. These observations represent something more profound than procedural failures—they expose cognitive and knowledge management vulnerabilities that can undermine even the most well-intentioned quality systems..

Understanding these vulnerabilities through the lens of cognitive behavioral science and knowledge management principles provides a pathway to more robust and resilient quality systems. Instead of viewing these failures as isolated incidents or individual shortcomings, we should recognize them as predictable patterns that emerge from systematic limitations in how humans process information and organizations manage knowledge. This recognition opens the door to designing quality systems that work with, rather than against, these cognitive realities

The Framework Foundation of Risk Management Excellence

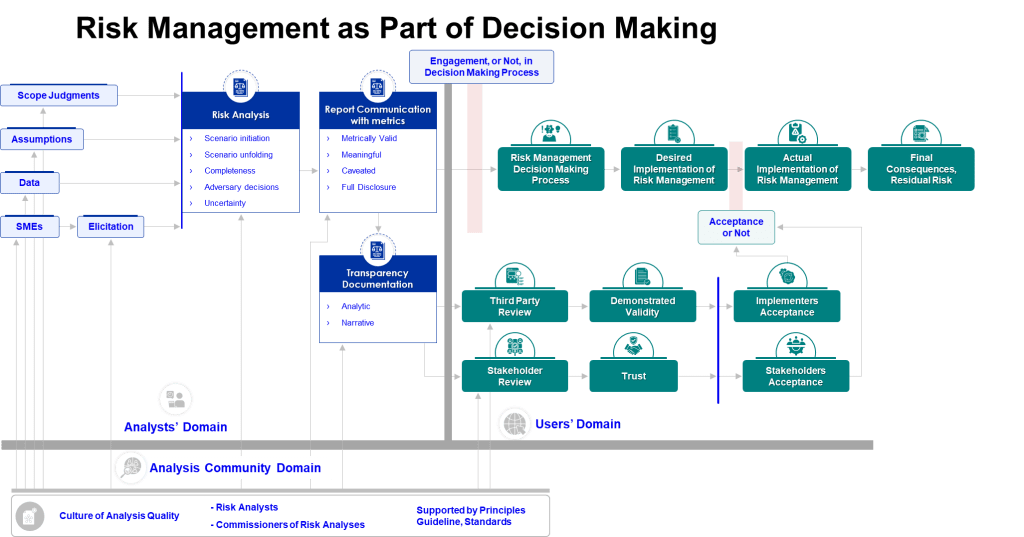

Risk management operates fundamentally as a framework rather than a rigid methodology, providing the structural architecture that enables systematic approaches to identifying, assessing, and controlling uncertainties that could impact pharmaceutical quality objectives. This distinction proves crucial for understanding how cognitive biases manifest within risk management systems and how excellence-driven quality systems can effectively address them.

A framework establishes the high-level structure, principles, and processes for managing risks systematically while allowing flexibility in execution and adaptation to specific organizational contexts. The framework defines structural components like governance and culture, strategy and objective-setting, and performance monitoring that establish the scaffolding for risk management without prescribing inflexible procedures.

Within this framework structure, organizations deploy specific methodological elements as tools for executing particular risk management tasks. These methodologies include techniques such as Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), brainstorming sessions, SWOT analysis, and risk surveys for identification activities, while assessment methodologies encompass qualitative and quantitative approaches including statistical models and scenario analysis. The critical insight is that frameworks provide the systematic architecture that counters cognitive biases, while methodologies are specific techniques deployed within this structure.

This framework approach directly addresses the three PIC/S observations by establishing systematic requirements that counter natural cognitive tendencies. Standardized framework processes force systematic consideration of risk factors rather than allowing teams to rely on intuitive pattern recognition that might be influenced by availability bias or anchoring on familiar scenarios. Documented decision rationales required by framework approaches make assumptions explicit and subject to challenge, preventing the perpetuation of unjustified beliefs that may have become embedded in organizational practices.

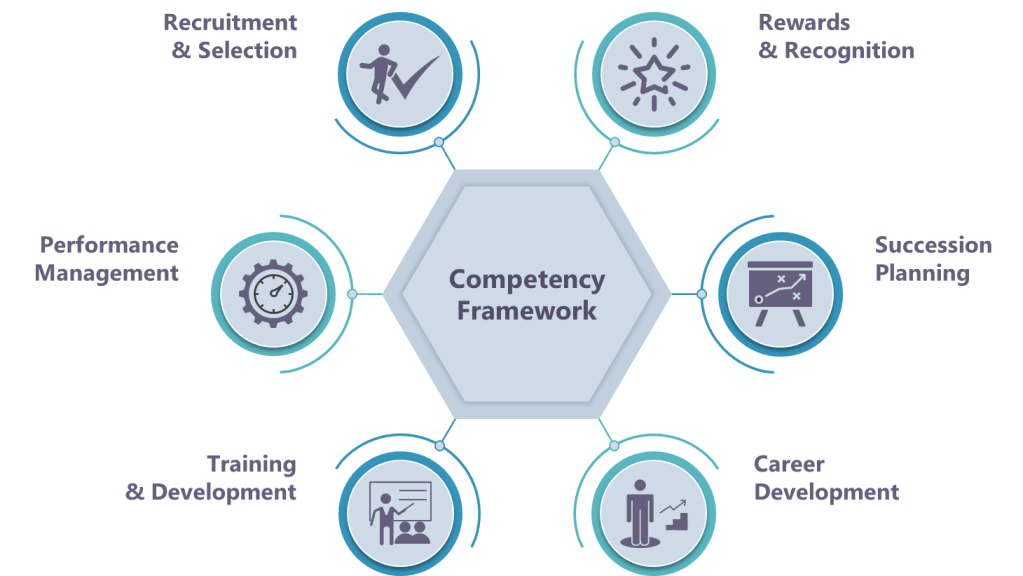

The governance components inherent in risk management frameworks address the expertise and knowledge management challenges identified in PIC/S guidance by establishing clear roles, responsibilities, and requirements for appropriate expertise involvement in risk assessment activities. Rather than leaving expertise requirements to chance or individual judgment, frameworks systematically define when specialized knowledge is required and how it should be accessed and validated.

ICH Q9’s approach to Quality Risk Management in pharmaceuticals demonstrates this framework principle through its emphasis on scientific knowledge and proportionate formality. The guideline establishes framework requirements that risk assessments be “based on scientific knowledge and linked to patient protection” while allowing methodological flexibility in how these requirements are met. This framework approach provides systematic protection against the cognitive biases that lead to unjustified assumptions while supporting the knowledge management processes necessary for complete risk identification and appropriate tool application.

The continuous improvement cycles embedded in mature risk management frameworks provide ongoing validation of cognitive bias mitigation effectiveness through operational performance data. These systematic feedback loops enable organizations to identify when initial assumptions prove incorrect or when changing conditions alter risk profiles, supporting the adaptive learning required for sustained excellence in pharmaceutical risk management.

The Systematic Nature of Risk Assessment Failure

Unjustified Assumptions: When Experience Becomes Liability

The first PIC/S observation—unjustified assumptions—represents perhaps the most insidious failure mode in pharmaceutical risk management. These are decisions made without sufficient scientific evidence or rational basis, often arising from what appears to be strength: extensive experience with familiar processes. The irony is that the very expertise we rely upon can become a source of systematic error when it leads to unfounded confidence in our understanding.

This phenomenon manifests most clearly in what cognitive scientists call anchoring bias—the tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information encountered when making decisions. In pharmaceutical risk assessments, this might appear as teams anchoring on historical performance data without adequately considering how process changes, equipment aging, or supply chain modifications might alter risk profiles. The assumption becomes: “This process has worked safely for five years, so the risk profile remains unchanged.”

Confirmation bias compounds this issue by causing assessors to seek information that confirms their existing beliefs while ignoring contradictory evidence. Teams may unconsciously filter available data to support predetermined conclusions about process reliability or control effectiveness. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where assumptions become accepted facts, protected from challenge by selective attention to supporting evidence.

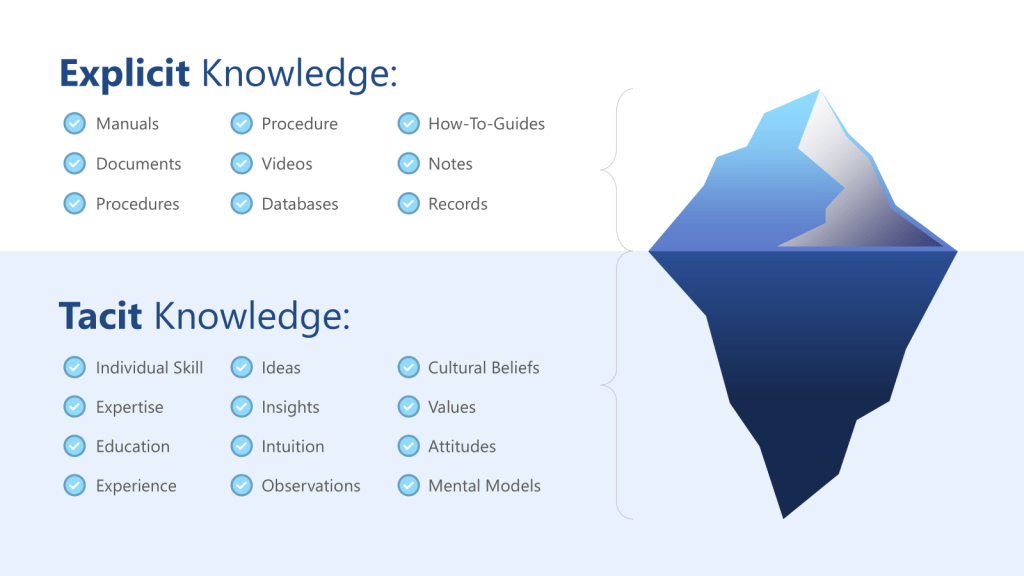

The knowledge management dimension of this failure is equally significant. Organizations often lack systematic approaches to capturing and validating the assumptions embedded in institutional knowledge. Tacit knowledge—the experiential, intuitive understanding that experts develop over time—becomes problematic when it remains unexamined and unchallenged. Without explicit processes to surface and test these assumptions, they become invisible constraints on risk assessment effectiveness.

Incomplete Risk Identification: The Boundaries of Awareness

The second observation—incomplete identification of risks or inadequate information—reflects systematic failures in the scope and depth of risk assessment activities. This represents more than simple oversight; it demonstrates how cognitive limitations and organizational boundaries constrain our ability to identify potential hazards comprehensively.

Availability bias plays a central role in this failure mode. Risk assessment teams naturally focus on hazards that are easily recalled or recently experienced, leading to overemphasis on dramatic but unlikely events while underestimating more probable but less memorable risks. A team might spend considerable time analyzing the risk of catastrophic equipment failure while overlooking the cumulative impact of gradual process drift or material variability.

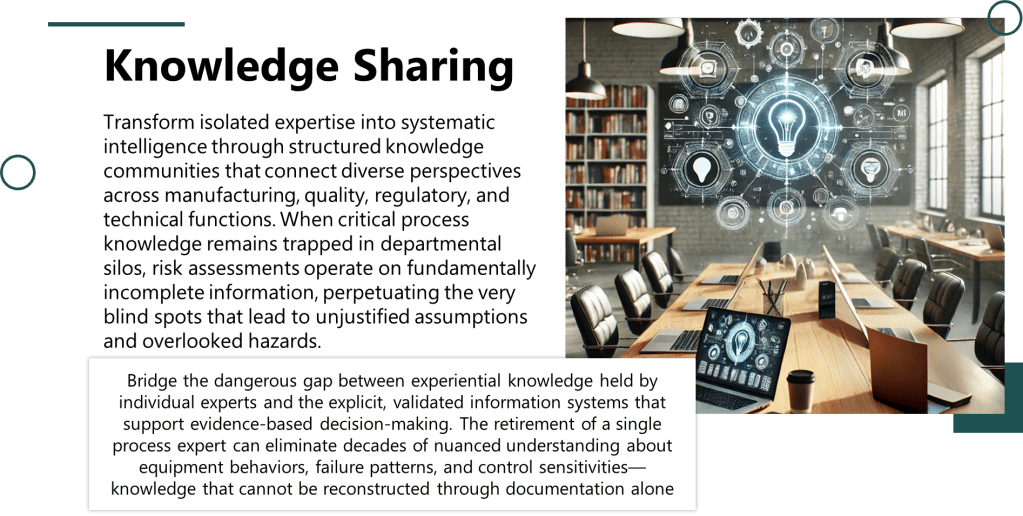

The knowledge management implications are profound. Organizations often struggle with knowledge that exists in isolated pockets of expertise. Critical information about process behaviors, failure modes, or control limitations may be trapped within specific functional areas or individual experts. Without systematic mechanisms to aggregate and synthesize distributed knowledge, risk assessments operate on fundamentally incomplete information.

Groupthink and organizational boundaries further constrain risk identification. When risk assessment teams are composed of individuals from similar backgrounds or organizational levels, they may share common blind spots that prevent recognition of certain hazard categories. The pressure to reach consensus can suppress dissenting views that might identify overlooked risks.

Inappropriate Tool Application: When Methodology Becomes Mythology

The third observation—lack of relevant experience with process assessment and inappropriate use of risk assessment tools—reveals how methodological sophistication can mask fundamental misunderstanding. This failure mode is particularly dangerous because it generates false confidence in risk assessment conclusions while obscuring the limitations of the analysis.

Overconfidence bias drives teams to believe they have more expertise than they actually possess, leading to misapplication of complex risk assessment methodologies. A team might apply Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) to a novel process without adequate understanding of either the methodology’s limitations or the process’s unique characteristics. The resulting analysis appears scientifically rigorous while providing misleading conclusions about risk levels and control effectiveness.

This connects directly to knowledge management failures in expertise distribution and access. Organizations may lack systematic approaches to identifying when specialized knowledge is required for risk assessments and ensuring that appropriate expertise is available when needed. The result is risk assessments conducted by well-intentioned teams who lack the specific knowledge required for accurate analysis.

The problem is compounded when organizations rely heavily on external consultants or standardized methodologies without developing internal capabilities for critical evaluation. While external expertise can be valuable, sole reliance on these resources may result in inappropriate conclusions or a lack of ownership of the assessment, as the PIC/S guidance explicitly warns.

The Role of Negative Reasoning in Risk Assessment

The research on causal reasoning versus negative reasoning from Energy Safety Canada provides additional insight into systematic failures in pharmaceutical risk assessments. Traditional root cause analysis often focuses on what did not happen rather than what actually occurred—identifying “counterfactuals” such as “operators not following procedures” or “personnel not stopping work when they should have.”

This approach, termed “negative reasoning,” is fundamentally flawed because what was not happening cannot create the outcomes we experienced. These counterfactuals “exist only in retrospection and never actually influenced events,” yet they dominate many investigation conclusions. In risk assessment contexts, this manifests as teams focusing on the absence of desired behaviors or controls rather than understanding the positive factors that actually influence system performance.

The shift toward causal reasoning requires understanding what actually occurred and what factors positively influenced the outcomes observed.

Knowledge-Enabled Decision Making

The intersection of cognitive science and knowledge management reveals how organizations can design systems that support better risk assessment decisions. Knowledge-enabled decision making requires structures that make relevant information accessible at the point of decision while supporting the cognitive processes necessary for accurate analysis.

This involves several key elements:

Structured knowledge capture that explicitly identifies assumptions, limitations, and context for recorded information. Rather than simply documenting conclusions, organizations must capture the reasoning process and evidence base that supports risk assessment decisions.

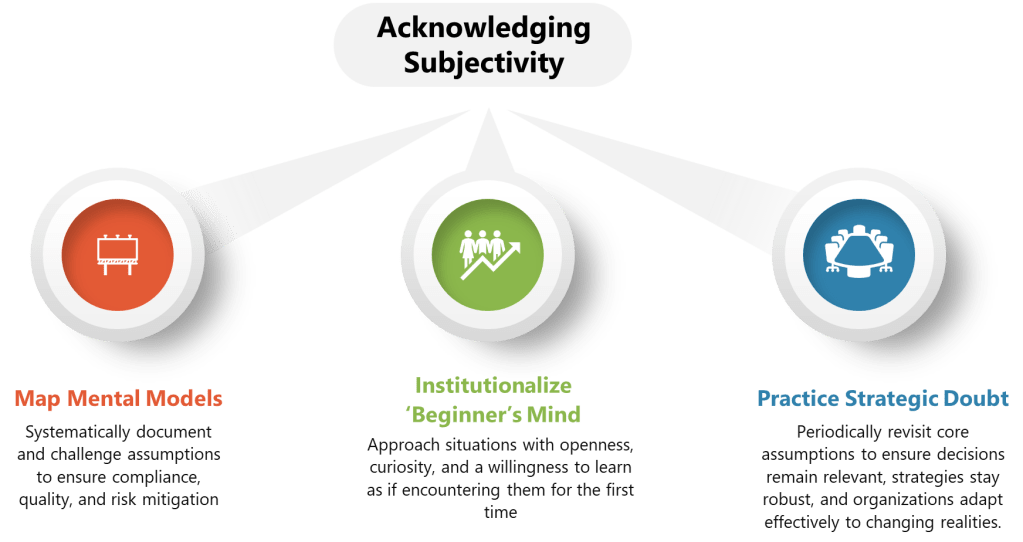

Knowledge validation systems that systematically test assumptions embedded in organizational knowledge. This includes processes for challenging accepted wisdom and updating mental models when new evidence emerges.

Expertise networks that connect decision-makers with relevant specialized knowledge when required. Rather than relying on generalist teams for all risk assessments, organizations need systematic approaches to accessing specialized expertise when process complexity or novelty demands it.

Decision support systems that prompt systematic consideration of potential biases and alternative explanations.

Excellence and Elegance: Designing Quality Systems for Cognitive Reality

Structured Decision-Making Processes

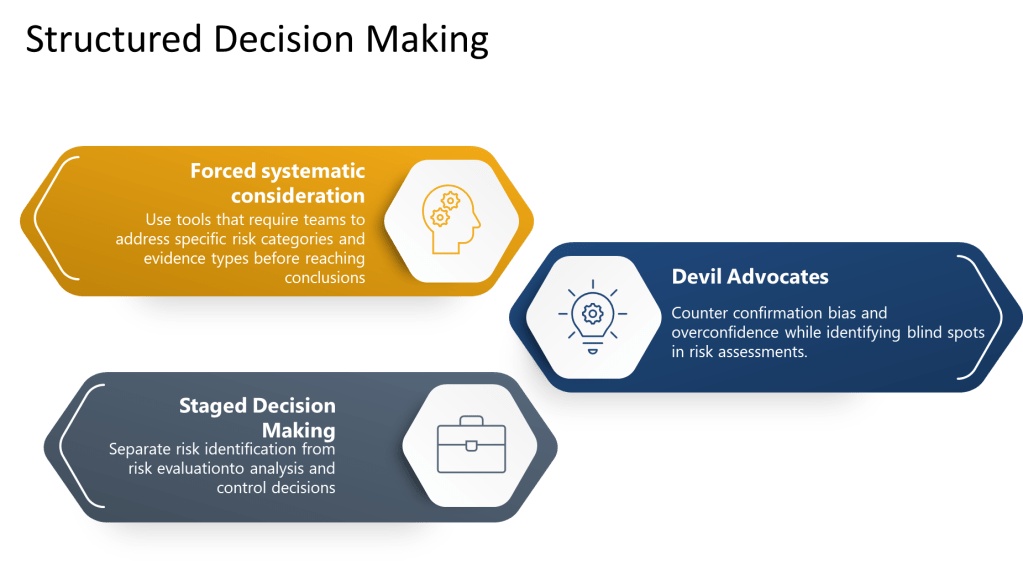

Excellence in pharmaceutical quality systems requires moving beyond hoping that individuals will overcome cognitive limitations through awareness alone. Instead, organizations must design structured decision-making processes that systematically counter known biases while supporting comprehensive risk identification and analysis.

Forced systematic consideration involves using checklists, templates, and protocols that require teams to address specific risk categories and evidence types before reaching conclusions. Rather than relying on free-form discussion that may be influenced by availability bias or groupthink, these tools ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant factors.

Devil’s advocate processes systematically introduce alternative perspectives and challenge preferred conclusions. By assigning specific individuals to argue against prevailing views or identify overlooked risks, organizations can counter confirmation bias and overconfidence while identifying blind spots in risk assessments.

Staged decision-making separates risk identification from risk evaluation, preventing premature closure and ensuring adequate time for comprehensive hazard identification before moving to analysis and control decisions.

Multi-Perspective Analysis and Diverse Assessment Teams

Cognitive diversity in risk assessment teams provides natural protection against individual and group biases. This goes beyond simple functional representation to include differences in experience, training, organizational level, and thinking styles that can identify risks and solutions that homogeneous teams might miss.

Cross-functional integration ensures that risk assessments benefit from different perspectives on process performance, control effectiveness, and potential failure modes. Manufacturing, quality assurance, regulatory affairs, and technical development professionals each bring different knowledge bases and mental models that can reveal different aspects of risk.

External perspectives through consultants, subject matter experts from other sites, or industry benchmarking can provide additional protection against organizational blind spots. However, as the PIC/S guidance emphasizes, these external resources should facilitate and advise rather than replace internal ownership and accountability.

Rotating team membership for ongoing risk assessment activities prevents the development of group biases and ensures fresh perspectives on familiar processes. This also supports knowledge transfer and prevents critical risk assessment capabilities from becoming concentrated in specific individuals.

Evidence-Based Analysis Requirements

Scientific justification for all risk assessment conclusions requires teams to base their analysis on objective, verifiable data rather than assumptions or intuitive judgments. This includes collecting comprehensive information about process performance, material characteristics, equipment reliability, and environmental factors before drawing conclusions about risk levels.

Assumption documentation makes implicit beliefs explicit and subject to challenge. Any assumptions made during risk assessment must be clearly identified, justified with available evidence, and flagged for future validation. This transparency helps identify areas where additional data collection may be needed and prevents assumptions from becoming accepted facts over time.

Evidence quality assessment evaluates the strength and reliability of information used to support risk assessment conclusions. This includes understanding limitations, uncertainties, and potential sources of bias in the data itself.

Structured uncertainty analysis explicitly addresses areas where knowledge is incomplete or confidence is low. Rather than treating uncertainty as a weakness to be minimized, mature quality systems acknowledge uncertainty and design controls that remain effective despite incomplete information.

Continuous Monitoring and Reassessment Systems

Performance validation provides ongoing verification of risk assessment accuracy through operational performance data. The PIC/S guidance emphasizes that risk assessments should be “periodically reviewed for currency and effectiveness” with systems to track how well predicted risks align with actual experience.

Assumption testing uses operational data to validate or refute assumptions embedded in risk assessments. When monitoring reveals discrepancies between predicted and actual performance, this triggers systematic review of the original assessment to identify potential sources of bias or incomplete analysis.

Feedback loops ensure that lessons learned from risk assessment performance are incorporated into future assessments. This includes both successful risk predictions and instances where significant risks were initially overlooked.

Adaptive learning systems use accumulated experience to improve risk assessment methodologies and training programs. Organizations can track patterns in assessment effectiveness to identify systematic biases or knowledge gaps that require attention.

Knowledge Management as the Foundation of Cognitive Excellence

The Critical Challenge of Tacit Knowledge Capture

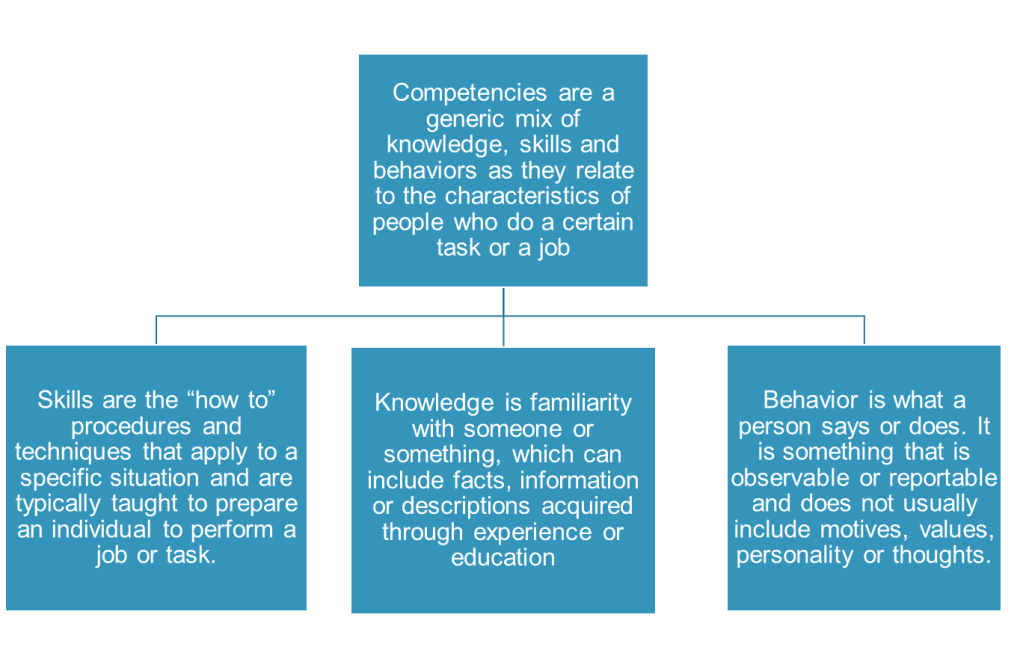

ICH Q10’s definition of knowledge management as “a systematic approach to acquiring, analysing, storing and disseminating information related to products, manufacturing processes and components” provides the regulatory framework, but the cognitive dimensions of knowledge management are equally critical. The distinction between tacit knowledge (experiential, intuitive understanding) and explicit knowledge (documented procedures and data) becomes crucial when designing systems to support effective risk assessment.

Tacit knowledge capture represents one of the most significant challenges in pharmaceutical quality systems. The experienced process engineer who can “feel” when a process is running correctly possesses invaluable knowledge, but this knowledge remains vulnerable to loss through retirements, organizational changes, or simply the passage of time. More critically, tacit knowledge often contains embedded assumptions that may become outdated as processes, materials, or environmental conditions change.

Structured knowledge elicitation processes systematically capture not just what experts know, but how they know it—the cues, patterns, and reasoning processes that guide their decision-making. This involves techniques such as cognitive interviewing, scenario-based discussions, and systematic documentation of decision rationales that make implicit knowledge explicit and subject to validation.

Knowledge validation and updating cycles ensure that captured knowledge remains current and accurate. This is particularly important for tacit knowledge, which may be based on historical conditions that no longer apply. Systematic processes for testing and updating knowledge prevent the accumulation of outdated assumptions that can compromise risk assessment effectiveness.

Expertise Distribution and Access

Knowledge networks provide systematic approaches to connecting decision-makers with relevant expertise when complex risk assessments require specialized knowledge. Rather than assuming that generalist teams can address all risk assessment challenges, mature organizations develop capabilities to identify when specialized expertise is required and ensure it is accessible when needed.

Expertise mapping creates systematic inventories of knowledge and capabilities distributed throughout the organization. This includes not just formal qualifications and roles, but understanding of specific process knowledge, problem-solving experience, and decision-making capabilities that may be relevant to risk assessment activities.

Dynamic expertise allocation ensures that appropriate knowledge is available for specific risk assessment challenges. This might involve bringing in experts from other sites for novel process assessments, engaging specialists for complex technical evaluations, or providing access to external expertise when internal capabilities are insufficient.

Knowledge accessibility systems make relevant information available at the point of decision-making through searchable databases, expert recommendation systems, and structured repositories that support rapid access to historical decisions, lessons learned, and validated approaches.

Knowledge Quality and Validation

Systematic assumption identification makes embedded beliefs explicit and subject to validation. Knowledge management systems must capture not just conclusions and procedures, but the assumptions and reasoning that support them. This enables systematic testing and updating when new evidence emerges.

Evidence-based knowledge validation uses operational performance data, scientific literature, and systematic observation to test the accuracy and currency of organizational knowledge. This includes both confirming successful applications and identifying instances where accepted knowledge may be incomplete or outdated.

Knowledge audit processes systematically evaluate the quality, completeness, and accessibility of knowledge required for effective risk assessment. This includes identifying knowledge gaps that may compromise assessment effectiveness and developing plans to address critical deficiencies.

Continuous knowledge improvement integrates lessons learned from risk assessment performance into organizational knowledge bases. When assessments prove accurate or identify overlooked risks, these experiences become part of organizational learning that improves future performance.

Integration with Risk Assessment Processes

Knowledge-enabled risk assessment systematically integrates relevant organizational knowledge into risk evaluation processes. This includes access to historical performance data, previous risk assessments for similar situations, lessons learned from comparable processes, and validated assumptions about process behaviors and control effectiveness.

Decision support integration provides risk assessment teams with structured access to relevant knowledge at each stage of the assessment process. This might include automated recommendations for relevant expertise, access to similar historical assessments, or prompts to consider specific knowledge domains that may be relevant.

Knowledge visualization and analytics help teams identify patterns, relationships, and insights that might not be apparent from individual data sources. This includes trend analysis, correlation identification, and systematic approaches to integrating information from multiple sources.

Real-time knowledge validation uses ongoing operational performance to continuously test and refine knowledge used in risk assessments. Rather than treating knowledge as static, these systems enable dynamic updating based on accumulating evidence and changing conditions.

A Maturity Model for Cognitive Excellence in Risk Management

Level 1: Reactive – The Bias-Blind Organization

Organizations at the reactive level operate with ad hoc risk assessments that rely heavily on individual judgment with minimal recognition of cognitive bias effects. Risk assessments are typically performed by whoever is available rather than teams with appropriate expertise, and conclusions are based primarily on immediate experience or intuitive responses.

Knowledge management characteristics at this level include isolated expertise with no systematic capture or sharing mechanisms. Critical knowledge exists primarily as tacit knowledge held by specific individuals, creating vulnerabilities when personnel changes occur. Documentation is minimal and typically focused on conclusions rather than reasoning processes or supporting evidence.

Cognitive bias manifestations are pervasive but unrecognized. Teams routinely fall prey to anchoring, confirmation bias, and availability bias without awareness of these influences on their conclusions. Unjustified assumptions are common and remain unchallenged because there are no systematic processes to identify or test them.

Decision-making processes lack structure and repeatability. Risk assessments may produce different conclusions when performed by different teams or at different times, even when addressing identical situations. There are no systematic approaches to ensuring comprehensive risk identification or validating assessment conclusions.

Typical challenges include recurring problems despite seemingly adequate risk assessments, inconsistent risk assessment quality across different teams or situations, and limited ability to learn from assessment experience. Organizations at this level often experience surprise failures where significant risks were not identified during formal risk assessment processes.

Level 2: Awareness – Recognizing the Problem

Organizations advancing to the awareness level demonstrate basic recognition of cognitive bias risks with inconsistent application of structured methods. There is growing understanding that human judgment limitations can affect risk assessment quality, but systematic approaches to addressing these limitations are incomplete or irregularly applied.

Knowledge management progress includes beginning attempts at knowledge documentation and expert identification. Organizations start to recognize the value of capturing expertise and may implement basic documentation requirements or expert directories. However, these efforts are often fragmented and lack systematic integration with risk assessment processes.

Cognitive bias recognition becomes more systematic, with training programs that help personnel understand common bias types and their potential effects on decision-making. However, awareness does not consistently translate into behavior change, and bias mitigation techniques are applied inconsistently across different assessment situations.

Decision-making improvements include basic templates or checklists that promote more systematic consideration of risk factors. However, these tools may be applied mechanically without deep understanding of their purpose or integration with broader quality system objectives.

Emerging capabilities include better documentation of assessment rationales, more systematic involvement of diverse perspectives in some assessments, and beginning recognition of the need for external expertise in complex situations. However, these practices are not yet embedded consistently throughout the organization.

Level 3: Systematic – Building Structured Defenses

Level 3 organizations implement standardized risk assessment protocols with built-in bias checks and documented decision rationales. There is systematic recognition that cognitive limitations require structured countermeasures, and processes are designed to promote more reliable decision-making.

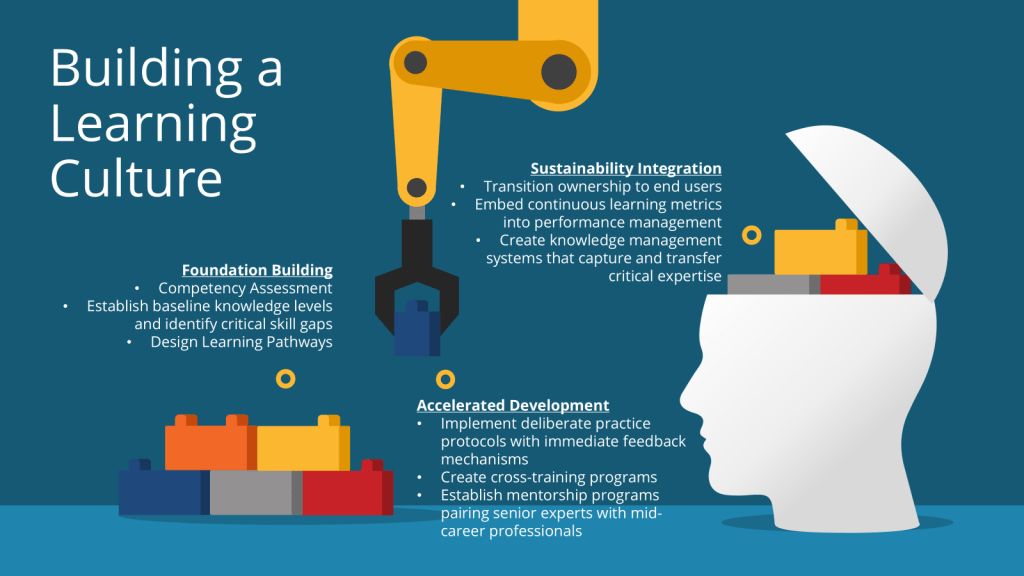

Knowledge management formalization includes formal knowledge management processes including expert networks and structured knowledge capture. Organizations develop systematic approaches to identifying, documenting, and sharing expertise relevant to risk assessment activities. Knowledge is increasingly treated as a strategic asset requiring active management.

Bias mitigation integration embeds cognitive bias awareness and countermeasures into standard risk assessment procedures. This includes systematic use of devil’s advocate processes, structured approaches to challenging assumptions, and requirements for evidence-based justification of conclusions.

Structured decision processes ensure consistent application of comprehensive risk assessment methodologies with clear requirements for documentation, evidence, and review. Teams follow standardized approaches that promote systematic consideration of relevant risk factors while providing flexibility for situation-specific analysis.

Quality characteristics include more consistent risk assessment performance across different teams and situations, systematic documentation that enables effective review and learning, and better integration of risk assessment activities with broader quality system objectives.

Level 4: Integrated – Cultural Transformation

Level 4 organizations achieve cross-functional teams, systematic training, and continuous improvement processes with bias mitigation embedded in quality culture. Cognitive excellence becomes an organizational capability rather than a set of procedures, supported by culture, training, and systematic reinforcement.

Knowledge management integration fully integrates knowledge management with risk assessment processes and supports these with technology platforms. Knowledge flows seamlessly between different organizational functions and activities, with systematic approaches to maintaining currency and relevance of organizational knowledge assets.

Cultural integration creates organizational environments where systematic, evidence-based decision-making is expected and rewarded. Personnel at all levels understand the importance of cognitive rigor and actively support systematic approaches to risk assessment and decision-making.

Systematic training and development builds organizational capabilities in both technical risk assessment methodologies and cognitive skills required for effective application. Training programs address not just what tools to use, but how to think systematically about complex risk assessment challenges.

Continuous improvement mechanisms systematically analyze risk assessment performance to identify opportunities for enhancement and implement improvements in methodologies, training, and support systems.

Level 5: Optimizing – Predictive Intelligence

Organizations at the optimizing level implement predictive analytics, real-time bias detection, and adaptive systems that learn from assessment performance. These organizations leverage advanced technologies and systematic approaches to achieve exceptional performance in risk assessment and management.

Predictive capabilities enable organizations to anticipate potential risks and bias patterns before they manifest in assessment failures. This includes systematic monitoring of assessment performance, early warning systems for potential cognitive failures, and proactive adjustment of assessment approaches based on accumulated experience.

Adaptive learning systems continuously improve organizational capabilities based on performance feedback and changing conditions. These systems can identify emerging patterns in risk assessment challenges and automatically adjust methodologies, training programs, and support systems to maintain effectiveness.

Industry leadership characteristics include contributing to industry knowledge and best practices, serving as benchmarks for other organizations, and driving innovation in risk assessment methodologies and cognitive excellence approaches.

Implementation Strategies: Building Cognitive Excellence

Training and Development Programs

Cognitive bias awareness training must go beyond simple awareness to build practical skills in bias recognition and mitigation. Effective programs use case studies from pharmaceutical manufacturing to illustrate how biases can lead to serious consequences and provide hands-on practice with bias recognition and countermeasure application.

Critical thinking skill development builds capabilities in systematic analysis, evidence evaluation, and structured problem-solving. These programs help personnel recognize when situations require careful analysis rather than intuitive responses and provide tools for engaging systematic thinking processes.

Risk assessment methodology training combines technical instruction in formal risk assessment tools with cognitive skills required for effective application. This includes understanding when different methodologies are appropriate, how to adapt tools for specific situations, and how to recognize and address limitations in chosen approaches.

Knowledge management skills help personnel contribute effectively to organizational knowledge capture, validation, and sharing activities. This includes skills in documenting decision rationales, participating in knowledge networks, and using knowledge management systems effectively.

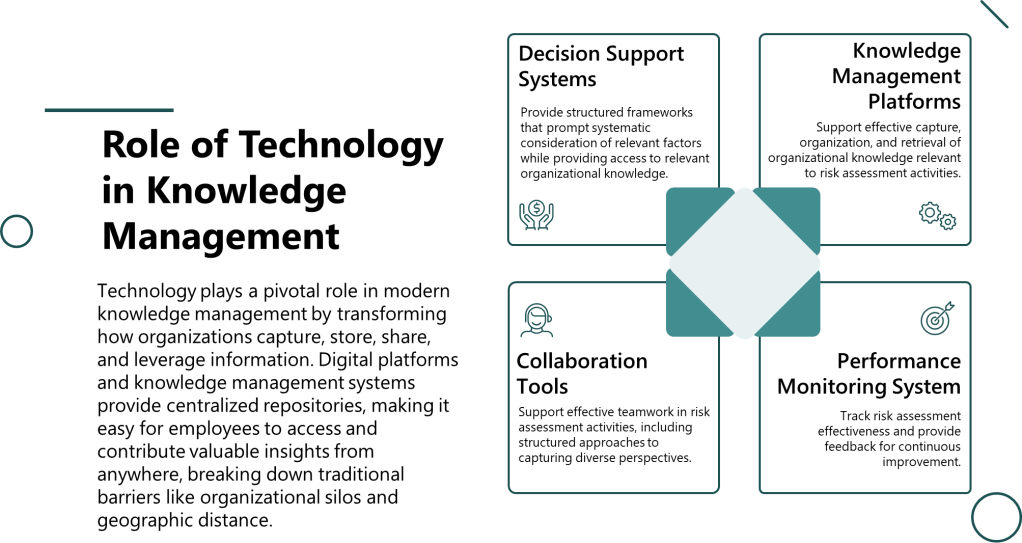

Technology Integration

Decision support systems provide structured frameworks that prompt systematic consideration of relevant factors while providing access to relevant organizational knowledge. These systems help teams engage appropriate cognitive processes while avoiding common bias traps.

Knowledge management platforms support effective capture, organization, and retrieval of organizational knowledge relevant to risk assessment activities. Advanced systems can provide intelligent recommendations for relevant expertise, historical assessments, and validated approaches based on assessment context.

Performance monitoring systems track risk assessment effectiveness and provide feedback for continuous improvement. These systems can identify patterns in assessment performance that suggest systematic biases or knowledge gaps requiring attention.

Collaboration tools support effective teamwork in risk assessment activities, including structured approaches to capturing diverse perspectives and managing group decision-making processes to avoid groupthink and other collective biases.

Organizational Culture Development

Leadership commitment demonstrates visible support for systematic, evidence-based approaches to risk assessment. This includes providing adequate time and resources for thorough analysis, recognizing effective risk assessment performance, and holding personnel accountable for systematic approaches to decision-making.

Psychological safety creates environments where personnel feel comfortable challenging assumptions, raising concerns about potential risks, and admitting uncertainty or knowledge limitations. This requires organizational cultures that treat questioning and systematic analysis as valuable contributions rather than obstacles to efficiency.

Learning orientation emphasizes continuous improvement in risk assessment capabilities rather than simply achieving compliance with requirements. Organizations with strong learning cultures systematically analyze assessment performance to identify improvement opportunities and implement enhancements in methodologies and capabilities.

Knowledge sharing cultures actively promote the capture and dissemination of expertise relevant to risk assessment activities. This includes recognition systems that reward knowledge sharing, systematic approaches to capturing lessons learned, and integration of knowledge management activities with performance evaluation and career development.

Conducting a Knowledge Audit for Risk Assessment

Organizations beginning this journey should start with a systematic knowledge audit that identifies potential vulnerabilities in expertise availability and access. This audit should address several key areas:

Expertise mapping to identify knowledge holders, their specific capabilities, and potential vulnerabilities from personnel changes or workload concentration. This includes both formal expertise documented in job descriptions and informal knowledge that may be critical for effective risk assessment.

Knowledge accessibility assessment to evaluate how effectively relevant knowledge can be accessed when needed for risk assessment activities. This includes both formal systems such as databases and informal networks that provide access to specialized expertise.

Knowledge quality evaluation to assess the currency, accuracy, and completeness of knowledge used to support risk assessment decisions. This includes identifying areas where assumptions may be outdated or where knowledge gaps may compromise assessment effectiveness.

Cognitive bias vulnerability assessment to identify situations where systematic biases are most likely to affect risk assessment conclusions. This includes analyzing past assessment performance to identify patterns that suggest bias effects and evaluating current processes for bias mitigation effectiveness.

Designing Bias-Resistant Risk Assessment Processes

Structured assessment protocols should incorporate specific checkpoints and requirements designed to counter known cognitive biases. This includes mandatory consideration of alternative explanations, requirements for external validation of conclusions, and systematic approaches to challenging preferred solutions.

Team composition guidelines should ensure appropriate cognitive diversity while maintaining technical competence. This includes balancing experience levels, functional backgrounds, and thinking styles to maximize the likelihood of identifying diverse perspectives on risk assessment challenges.

Evidence requirements should specify the types and quality of information required to support different types of risk assessment conclusions. This includes guidelines for evaluating evidence quality, addressing uncertainty, and documenting limitations in available information.

Review and validation processes should provide systematic quality checks on risk assessment conclusions while identifying potential bias effects. This includes independent review requirements, structured approaches to challenging conclusions, and systematic tracking of assessment performance over time.

Building Knowledge-Enabled Decision Making

Integration strategies should systematically connect knowledge management activities with risk assessment processes. This includes providing risk assessment teams with structured access to relevant organizational knowledge and ensuring that assessment conclusions contribute to organizational learning.

Technology selection should prioritize systems that enhance rather than replace human judgment while providing effective support for systematic decision-making processes. This includes careful evaluation of user interface design, integration with existing workflows, and alignment with organizational culture and capabilities.

Performance measurement should track both risk assessment effectiveness and knowledge management performance to ensure that both systems contribute effectively to organizational objectives. This includes metrics for knowledge quality, accessibility, and utilization as well as traditional risk assessment performance indicators.

Continuous improvement processes should systematically analyze performance in both risk assessment and knowledge management to identify enhancement opportunities and implement improvements in methodologies, training, and support systems.

Excellence Through Systematic Cognitive Development

The journey toward cognitive excellence in pharmaceutical risk management requires fundamental recognition that human cognitive limitations are not weaknesses to be overcome through training alone, but systematic realities that must be addressed through thoughtful system design. The PIC/S observations of unjustified assumptions, incomplete risk identification, and inappropriate tool application represent predictable patterns that emerge when sophisticated professionals operate without systematic support for cognitive excellence.

Excellence in this context means designing quality systems that work with human cognitive capabilities rather than against them. This requires integrating knowledge management principles with cognitive science insights to create environments where systematic, evidence-based decision-making becomes natural and sustainable. It means moving beyond hope that awareness will overcome bias toward systematic implementation of structures, processes, and cultures that promote cognitive rigor.

Elegance lies in recognizing that the most sophisticated risk assessment methodologies are only as effective as the cognitive processes that apply them. True elegance in quality system design comes from seamlessly integrating technical excellence with cognitive support, creating systems where the right decisions emerge naturally from the intersection of human expertise and systematic process.

Organizations that successfully implement these approaches will develop competitive advantages that extend far beyond regulatory compliance. They will build capabilities in systematic decision-making that improve performance across all aspects of pharmaceutical quality management. They will create resilient systems that can adapt to changing conditions while maintaining consistent effectiveness. Most importantly, they will develop cultures of excellence that attract and retain exceptional talent while continuously improving their capabilities.

The framework presented here provides a roadmap for this transformation, but each organization must adapt these principles to their specific context, culture, and capabilities. The maturity model offers a path for progressive development that builds capabilities systematically while delivering value at each stage of the journey.

As we face increasingly complex pharmaceutical manufacturing challenges and evolving regulatory expectations, the organizations that invest in systematic cognitive excellence will be best positioned to protect patient safety while achieving operational excellence. The choice is not whether to address these cognitive foundations of quality management, but how quickly and effectively we can build the capabilities required for sustained success in an increasingly demanding environment.

The cognitive foundations of pharmaceutical quality excellence represent both opportunity and imperative. The opportunity lies in developing systematic capabilities that transform good intentions into consistent results. The imperative comes from recognizing that patient safety depends not just on our technical knowledge and regulatory compliance, but on our ability to think clearly and systematically about complex risks in an uncertain world.

Reflective Questions for Implementation

How might you assess your organization’s current vulnerability to the three PIC/S observations in your risk management practices? What patterns in past risk assessment performance might indicate systematic cognitive biases affecting your decision-making processes?

Where does critical knowledge for risk assessment currently reside in your organization, and how accessible is it when decisions must be made? What knowledge audit approach would be most valuable for identifying vulnerabilities in your current risk management capabilities?

Which level of the cognitive bias mitigation maturity model best describes your organization’s current state, and what specific capabilities would be required to advance to the next level? How might you begin building these capabilities while maintaining current operational effectiveness?

What systematic changes in training, process design, and cultural expectations would be required to embed cognitive excellence into your quality culture? How would you measure progress in building these capabilities and demonstrate their value to organizational leadership?