An effective change management system includes active knowledge management, leveraging existing process and product knowledge; capturing new knowledge gained during implementation of the change; and, transferring that knowledge in appropriate ways to all stakeholders.

Any quality system (any system) has as part of it’s major function transforming data into information; the acquisition and creation of knowledge; and the dissemination and using information and knowledge. A main pipe of process improvement is how to implicit knowledge and make it explicit. This is one of the reasons we spend so much time developing standardized work.

And yet I, like many quality professionals, have found myself sitting at a table or standing in front of a visual management board, and have some type of leader ask why we spend so much time training when we should be able to hire anyone with an appropriate level of experience and have them just do the job.

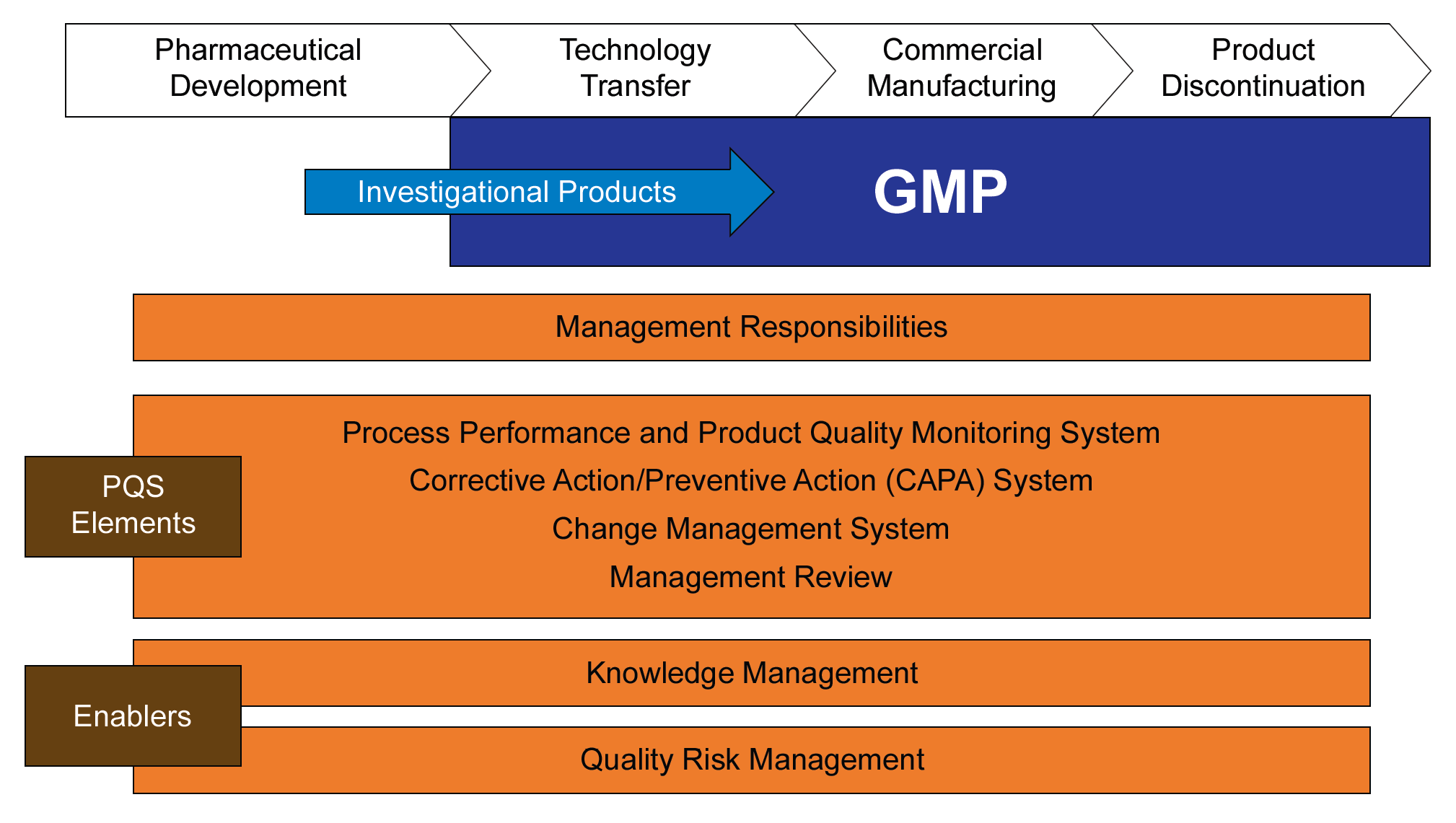

Systems are made up of four things – process, organization, people and technology. When folks think of change management, or root cause analysis, or similar quality processes and tools they tend to think the system is only about the activity we are engaging in. But change management (or root cause analysis or data integrity) is not that simple.

This is really two-fold. A person assessing a change is not just needing to be knowledgeable about how the change control process works, they need to be able to analyze the change to each and every process within the systems they represent, to understand how moving the levers and adjusting the buffers within this change influences each and everything they do, even it that’s to be able to make a concrete and definitive no impact statement.

So when we process improve our change management system (or similar quality processes) we are both improving how we manage change and how folks apply that thinking to all their other activities.

In less mature systems we end up having a lot of tacit knowledge in one person. You have that great SME who understands master data in the ERP and how changes impact it. In way to transfer that tacit knowledge to another person is a lot of socialization. It is experiential, active and a “living thing,” involving capturing knowledge by spending a lot of time with that person and having shared experience, which results in acquired skills and common mental models.

For example, my master-data guru needs to be involved in each and every change that might possibly involve the ERP or master-data. I might have reached the point where the procedure has large sections that give detailed instructions on when to involve the master-data guru in a change. The master-data guru spends a lot of time justifying no-impact. Otherwise, I might be having change after change forget to update master data. Which leads to deviations.

At this stage of maturity I’ve recognized I need a master data guru. I’ve identified the individual(s). Depending on maturity I either involve the master-data guru on every change or I’ve advanced enough that I have a decision tool that drives changes to the master-data guru.

So now either the master-data guru is becoming a pain point or we’ve had one too many changes that led to deviations because we failed to change master data in the ERP correctly. So we enter a process improvement cycle.

What we need to do here is make the master-data guru’s tacit knowledge explicit; we need to externalize this knowledge. We start building the tools that better define what never has impact, what always has impact, and what might have impact or be really unique. When a change has no impact, the change owner is able to note that and move on (no master-data guru involvement necessary). When it has definite impact the change owner is able to identify the actions required, knowing exactly what procedures to follow and how to execute those within a change. We still have a set of changes that will trigger the master-data guru’s involvement, but those are smaller in number and more complex in scope.

The steps we took to get here also allow us to more easily develop and train master-data gurus. Maybe we have a skills matrix and it is on development plans. Our training program now has the tools to allow internalization, the process of understanding and absorbing explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge held by the individual.

At this point I have the tools for my average change owner to know when to change master data and how-to-do it (this might not involve them actually doing master data management it is really knowing when to execute, and the outputs from and inputs back into the change management system) AND I have better mechanisms for producing master data experts. That’s the beauty here, the knowledge level required to execute change management properly is usually an expert level competency. By making that knowledge explicit I am serving multiple processes and interrelated systems.

To breakdown the process:

- Capture all the knowledge. Interview the SME(s), evaluate the use of the system, gather together all the procedures and training and user manuals and power point slides

- Assess what is valuable, what needs to be transferred

- Share this knowledge, and make sure others can understand it

- Contextualize into standard tools (job aids, user guides, checklists, templates, etc.)

- Apply the knowledge. Train others and also update your system processes (and maybe technology) to make sure the knowledge is used.

- Update – make sure the knowledge is sustained and regularly updated.

Change management has lots of inputs and outputs. As does data integrity and other quality systems. Understanding these interrelationships, and ensuring knowledge is appropriate, captured, and utilized, is a big way we improve and thrive.