Quality needs to be managed as a program, and as such, it must walk a delicate line between setting long-term goals, short-term goals, improvement priorities, and interacting with a suite of portfolios, programs, and KPIs. As quality professionals navigate increasingly complex regulatory landscapes, technological disruptions, and evolving customer expectations, the need for structured approaches to quality planning has never been greater.

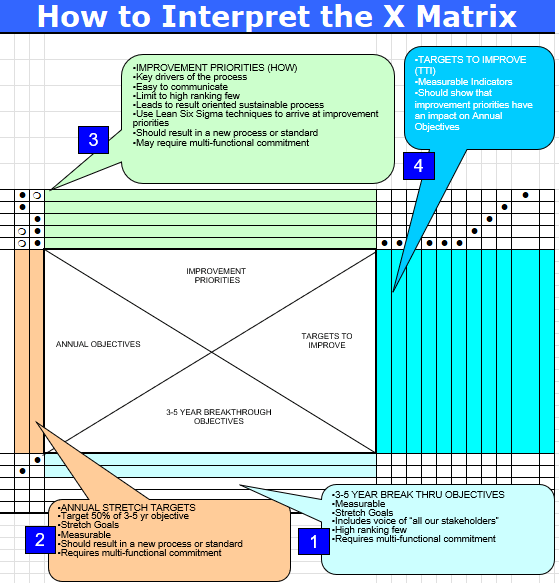

At the heart of this activity, I use an x-matrix, a powerful tool at the intersection of strategic planning and quality management. The X-Matrix provides a comprehensive framework that clarifies the chaos, visually representing how long-term quality objectives cascade into actionable initiatives with clear ownership and metrics – connecting the dots between aspiration and execution in a single, coherent framework.

Understanding the X-Matrix: Structure and Purpose

The X-Matrix is a strategic planning tool from Hoshin Kanri methodology that brings together multiple dimensions of organizational strategy onto a single page. Named for its distinctive X-shaped pattern of relationships, this tool enables us to visualize connections between long-term breakthroughs, annual objectives, improvement priorities, and measurable targets – all while clarifying ownership and resource allocation.

The X-Matrix is structured around four key quadrants that create its distinctive shape:

- South Quadrant (3-5 Year Breakthrough Objectives): These are the foundational, long-term quality goals that align with organizational vision and regulatory expectations. In quality contexts, these might include achieving specific quality maturity levels, establishing new quality paradigms, or fundamentally transforming quality systems.

- West Quadrant (Annual Objectives): These represent the quality priorities for the coming year that contribute directly to the longer-term breakthroughs. These objectives are specific enough to be actionable within a one-year timeframe.

- North Quadrant (Improvement Priorities): These are the specific initiatives, projects, and process improvements that will be undertaken to achieve the annual objectives. Each improvement priority should have clear ownership and resource allocation.

- East Quadrant (Targets/Metrics): These are the measurable indicators that will be used to track progress toward both annual objectives and breakthrough goals. In quality planning, these often include process capability indices, deviation rates, right-first-time metrics, and other key performance indicators.

The power of the X-Matrix lies in the correlation points where these quadrants intersect. These intersections show how initiatives support objectives and how objectives align with long-term goals. They create a clear line of sight from strategic quality vision to daily operations and improvement activities.

Why the X-Matrix Excels for Quality Planning

Traditional quality planning approaches often suffer from disconnection between strategic objectives and tactical activities. Quality initiatives may be undertaken in isolation, with limited understanding of how they contribute to broader organizational goals. The X-Matrix addresses this fragmentation through its integrated approach to planning.

The X-Matrix provides visibility into the interdependencies within your quality system. By mapping the relationships between long-term quality objectives, annual goals, improvement priorities, and key metrics, quality leaders can identify potential resource conflicts, capability gaps, and opportunities for synergy.

Developing an X-Matrix necessitates cross-functional input and alignment to ensure that quality objectives are not isolated but integrated with operations, regulatory, supply chain, and other critical functions. The development of an X-Matrix encourages the back-and-forth dialogue necessary to develop realistic, aligned goals.

Perhaps most importantly for quality organizations, the X-Matrix provides the structure and rigor to ensure quality planning is not left to chance. As the FDA and other regulatory bodies increasingly emphasize Quality Management Maturity (QMM) as a framework for evaluating pharmaceutical operations, the disciplined approach embodied in the X-Matrix becomes a competitive advantage. The matrix systematically considers resource constraints, capability requirements, and performance measures – all essential components of mature quality systems.

Mapping Modern Quality Challenges to the X-Matrix

The quality landscape is evolving rapidly, with several key challenges that must be addressed in any comprehensive quality planning effort. The X-Matrix provides an ideal framework for addressing these challenges systematically. Building on the post “The Challenges Ahead for Quality” we can start to build our an X-matrix.

Advanced Analytics and Digital Transformation

As data sources multiply and processing capabilities expand, quality organizations face increased expectations for data-driven insights and decision-making. An effective X-Matrix for quality planning couldinclude:

3-5 Year Breakthrough: Establish a predictive quality monitoring system that leverages advanced analytics to identify potential quality issues before they manifest.

Annual Objectives: Implement data visualization tools for key quality metrics; establish data governance framework for GxP data; develop predictive models for critical quality attributes.

Improvement Priorities: Create cross-functional data science capability; implement automated data capture for batch records; develop real-time dashboards for process parameters.

Metrics: Percentage of quality decisions made with data-driven insights; predictive model accuracy; reduction in quality investigation cycle time through analytics.

Operational Stability in Complex Supply Networks

As pharmaceutical manufacturing becomes increasingly globalized with complex supplier networks, operational stability emerges as a critical challenge. Operational stability represents the state where manufacturing and quality processes exhibit consistent, predictable performance over time with minimal unexpected variation. The X-Matrix can address this through:

3-5 Year Breakthrough: Achieve Level 4 (Proactive) operational stability across all manufacturing sites, networks and key suppliers.

Annual Objectives: Implement statistical process control for critical processes; establish supplier quality alignment program; develop operational stability metrics and monitoring system.

Improvement Priorities: Deploy SPC training and tools; conduct operational stability risk assessments; implement regular supplier quality reviews; establish cross-functional stability team.

Metrics: Process capability indices (Cp, Cpk); right-first-time batch rates; deviation frequency and severity patterns; supplier quality performance.

Using the X-Matrix to Address Validation Challenges

Validation presents unique challenges in modern pharmaceutical operations, particularly as data systems become more complex and interconnected. Handling complex data types and relationships can be time-consuming and difficult, while managing validation rules across large datasets becomes increasingly costly and challenging. The X-Matrix offers a structured approach to addressing these validation challenges:

3-5 Year Breakthrough: Establish a risk-based, continuous validation paradigm that accommodates rapidly evolving systems while maintaining compliance.

Annual Objectives: Implement risk-based validation approach for all GxP systems; establish automated testing capabilities for critical applications; develop validation strategy for AI/ML applications.

Improvement Priorities: Train validation team on risk-based approaches; implement validation tool for automated test execution; develop validation templates for different system types; establish validation center of excellence.

Metrics: Validation cycle time reduction; percentage of validation activities conducted via automated testing; validation resource efficiency; validation effectiveness (post-implementation defects).

This X-Matrix approach to validation challenges ensures that validation activities are not merely compliance exercises but strategic initiatives that support broader quality objectives. By connecting validation priorities to annual objectives and long-term breakthroughs, organizations can justify the necessary investments and resources while maintaining a clear focus on business value.

Connecting X-Matrix Planning to Quality Maturity Models

The FDA’s Quality Management Maturity (QMM) model provides a framework for assessing an organization’s progression from reactive quality management to optimized, continuous improvement. This model aligns perfectly with the X-Matrix planning approach, as both emphasize systematic progression toward excellence.

The X-Matrix can be structured to support advancement through quality maturity levels by targeting specific capabilities associated with each level:

| Maturity Level | X-Matrix Breakthrough Objective | Annual Objectives | Improvement Priorities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive (Level 1) | Move from reactive to controlled quality operations | Establish baseline quality metrics; implement basic SOPs; define critical quality attributes | Process mapping; basic training program; deviation management system |

| Controlled (Level 2) | Transition from controlled to predictive quality systems | Implement statistical monitoring; establish proactive quality planning; develop quality risk management | SPC implementation; risk assessment training; preventive maintenance program |

| Predictive (Level 3) | Advance from predictive to proactive quality operations | Establish leading indicators; implement knowledge management; develop cross-functional quality ownership | Predictive analytics capability; knowledge database; quality circles |

| Proactive (Level 4) | Progress from proactive to innovative quality systems | Implement continuous verification; establish quality innovation program; develop supplier quality maturity | Continuous process verification; innovation workshops; supplier development program |

| Innovative (Level 5) | Maintain and leverage innovative quality capabilities | Establish industry leading practices; develop quality thought leadership; implement next-generation quality approaches | Quality research initiatives; external benchmarking; technology innovation pilots |

This alignment between the X-Matrix and quality maturity models offers several advantages. First, it provides a clear roadmap for progression through maturity levels. Second, it helps organizations prioritize initiatives based on their current maturity level and desired trajectory. Finally, it creates a framework for measuring and communicating progress toward maturity goals.

Implementation Best Practices for Quality X-Matrix Planning

Implementing an X-Matrix approach to quality planning requires careful consideration of several key factors.

1. Start With Clear Strategic Quality Imperatives

The foundation of any effective X-Matrix is a clear set of strategic quality imperatives that align with broader organizational goals. These imperatives should be derived from:

- Regulatory expectations and trends

- Customer quality requirements

- Competitive quality positioning

- Organizational quality vision

These imperatives form the basis for the 3-5 year breakthrough objectives in the X-Matrix. Without this clarity, the remaining elements of the matrix will lack focus and alignment.

2. Leverage Cross-Functional Input

Quality does not exist in isolation; it intersects with every aspect of the organization. Effective X-Matrix planning requires input from operations, regulatory affairs, supply chain, R&D, and other functions. This cross-functional perspective ensures that quality objectives are realistic, supported by appropriate capabilities, and aligned with broader organizational priorities.

The catchball process from Hoshin Kanri provides an excellent framework for this cross-functional dialogue, allowing for iterative refinement of objectives, priorities, and metrics based on input from various stakeholders.

3. Focus on Critical Few Priorities

The power of the X-Matrix lies in its ability to focus organizational attention on the most critical priorities. Resist the temptation to include too many initiatives, objectives, or metrics. Instead, identify the vital few that will drive meaningful progress toward quality maturity and operational excellence.

This focus is particularly important in regulated environments where resource constraints are common and compliance demands can easily overwhelm improvement initiatives. A well-designed X-Matrix helps quality leaders maintain strategic focus amid the daily demands of compliance activities.

4. Establish Clear Ownership and Resource Allocation

The X-Matrix should clearly identify who is responsible for each improvement priority and what resources they will have available. This clarity is essential for execution and accountability. Without explicit ownership and resource allocation, even the most well-conceived quality initiatives may fail to deliver results.

The structure of the X-Matrix facilitates this clarity by explicitly mapping resources to initiatives and objectives. This mapping helps identify potential resource conflicts early and ensures that critical initiatives have the support they need.

Balancing Structure with Adaptability in Quality Planning

A potential criticism of highly structured planning approaches like the X-Matrix is that they may constrain adaptability and innovation. However, a well-designed X-Matrix actually enhances adaptability by providing a clear framework for evaluating and integrating new priorities. The structure of the matrix makes it apparent when new initiatives align with strategic objectives and when they represent potential distractions. This clarity helps quality leaders make informed decisions about where to focus limited resources when disruptions occur.

The key lies in building what might be called “bounded flexibility”—freedom to innovate within well-understood boundaries. By thoroughly understanding which process parameters truly impact critical quality attributes, organizations can focus stability efforts where they matter most while allowing flexibility elsewhere. The X-Matrix supports this balanced approach by clearly delineating strategic imperatives (where stability is essential) from tactical initiatives (where adaptation may be necessary).

Change management systems represent another critical mechanism for balancing stability with innovation. Well-designed change management ensures that innovations are implemented in a controlled manner that preserves operational stability. The X-Matrix can incorporate change management as a specific improvement priority, ensuring that the organization’s ability to adapt is explicitly addressed in quality planning.

The X-Matrix as the Engine of Quality Excellence

The X-Matrix represents a powerful approach to quality planning that addresses the complex challenges facing modern quality organizations. By providing a structured framework for aligning long-term quality objectives with annual goals, specific initiatives, and measurable targets, the X-Matrix helps quality leaders navigate complexity while maintaining strategic focus.

As regulatory bodies evolve toward Quality Management Maturity models, the systematic approach embodied in the X-Matrix will become increasingly valuable. Organizations that establish and maintain strong operational stability through structured planning will find themselves well-positioned for both compliance and competition in an increasingly demanding pharmaceutical landscape.

The journey toward quality excellence is not merely technical but cultural and organizational. It requires systematic approaches, appropriate metrics, and balanced objectives that recognize quality not as an end in itself but as a means to deliver value to patients, practitioners, and the business. The X-Matrix provides the framework needed to navigate this journey successfully, translating quality vision into tangible results that advance both organizational performance and patient outcomes.

By adopting the X-Matrix approach to quality planning, organizations can ensure that their quality initiatives are not isolated efforts but components of a coherent strategy that addresses current challenges while building the foundation for future excellence. In a world of increasing complexity and rising expectations, this structured yet flexible approach to quality planning may well be the difference between merely complying and truly excelling.