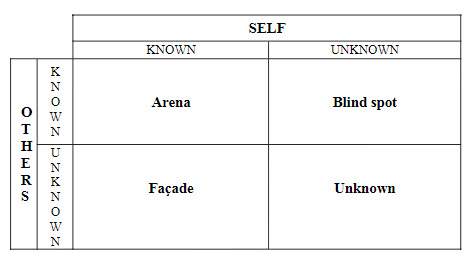

There are many forms of bias that we must be cognizant during problem solving and decision making.

That chart can be a little daunting. I’m just going to mention three of the more common biases.

- Attribution bias: When we do something well, we tend to think it’s because of our own merit. When we do something poorly, we tend to believe it was due to external factors (e.g. other people’s actions). When it comes to other people, we tend to think the opposite – if they did something well, we consider them lucky, and if they did something poorly, we tend to think it’s due to their personality or lack of skills.

- Confirmation bias: The tendency to seek out evidence that supports decisions and positions we’ve already embraced – regardless of whether the information is true – and putting less weight on facts that contradict them.

- Hindsight bias: The tendency to believe an event was predictable or preventable when looking at the sequence of events in hindsight. This can result in oversimplification of cause and effect and an exaggerated view that a person involved with an event could’ve prevented it. They didn’t know the outcome like you do now and likely couldn’t have predicted it with the information available at the time.

A few ways to address our biases include:

- Bouncing ideas off of others, especially those not involved in the discussion or decision.

- Surround yourself with a diverse group of people and do not be afraid to consider dissenting views. Actively listen.

- Imagine yourself in other’s shoes.

- Be mindful of your internal environment. If you’re struggling with a decision, take a moment to breathe. Don’t make decisions tired, hungry or stressed.

- Consider who is impacted by your decision (or lack of decision). Sometimes, looking at how others will be impacted by a given decision will help to clarify the decision for you.

The advantage of focusing on decision quality is that we have a process that allows us to ensure we are doing the right things consistently. By building mindfulness we can strive for good decisions, reducing subjectivity and effective problem-solving.