In the relentless march of quality and operational improvement, frameworks, methodologies and tools abound but true breakthrough is rare. There is a persistent challenge: organizations often become locked into their own best practices, relying on habitual process reforms that seldom address the deeper why of operational behavior. This “process myopia”—where the visible sequence of tasks occludes the real purpose—runs in parallel to risk blindness, leaving many organizations vulnerable to the slow creep of inefficiency, bias, and ultimately, quality failures.

The Jobs-to-Be-Done (JTBD) tool offers an effective method for reorientation. Rather than focusing on processes or systems as static routines, JTBD asks a deceptively simple question: What job are people actually hiring this process or tool to do? In deviation management, audit response, even risk assessment itself, the answer to this question is the gravitational center on which effective redesign can be based.

What Does It Mean to Hire a Process?

To “hire” a process—even when it is a regulatory obligation—means viewing the process not merely as a compliance requirement, but as a tool or mechanism that stakeholders use to achieve specific, desirable outcomes beyond simple adherence. In Jobs-to-Be-Done (JTBD), the idea of “hiring” a process reframes organizational behavior: stakeholders (such as quality professionals, operators, managers, or auditors) are seen as engaging with the process to get particular jobs done—such as ensuring product safety, demonstrating control to regulators, reducing future risk, or creating operational transparency.

When a process is regulatory-mandated—such as deviation management, change control, or batch release—the “hiring” metaphor recognizes two coexisting realities:

Dual Functions: Compliance and Value Creation

- Compliance Function: The organization must follow the process to satisfy legal, regulatory, or contractual obligations. Not following is not an option; it’s legally or organizationally enforced.

- Functional “Hiring”: Even for required processes, users “hire” the process to accomplish additional jobs—like protecting patients, facilitating learning from mistakes, or building organizational credibility. A well-designed process serves both external (regulatory) and internal (value-creating) goals.

Implications for Process Design

- Stakeholders still have choices in how they interact with the process—they can engage deeply (to learn and improve) or superficially (for box-checking), depending on how well the process helps them do their “real” job.

- If a process is viewed only as a regulatory tax, users will find ways to shortcut, minimally comply, or bypass the spirit of the requirement, undermining learning and risk mitigation.

- Effective design ensures the process delivers genuine value, making “compliance” a natural by-product of a process stakeholders genuinely want to “hire”—because it helps them achieve something meaningful and important.

Practical Example: Deviation Management

- Regulatory “Must”: Deviations must be documented and investigated under GMP.

- Users “Hire” the Process to: Identify real risks early, protect quality, learn from mistakes, and demonstrate control in audits.

- If the process enables those jobs well, it will be embraced and used effectively. If not, it becomes paperwork compliance—and loses its potential as a learning or risk-reduction tool.

To “hire” a process under regulatory obligation is to approach its use intentionally, ensuring it not only satisfies external requirements but also delivers real value for those required to use it. The ultimate goal is to design a process that people would choose to “hire” even if it were not mandatory—because it supports their intrinsic goals, such as maintaining quality, learning, and risk control.

Unpacking Jobs-to-Be-Done: The Roots of Customer-Centricity

Historical Genesis: From Marketing Myopia to Outcome-Driven Innovation

The JTBD’s intellectual lineage traces back to Theodore Levitt’s famous adage: “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole.” This insight, presented in his seminal 1960 Harvard Business Review article “Marketing Myopia,” underscores the fatal flaw of most process redesigns: overinvestment in features, tools, and procedures, while neglecting the underlying human need or outcome.

This thinking resonates strongly with Peter Drucker’s core dictum that “the purpose of a business is to create and keep a customer”—and that marketing and innovation, not internal optimization, are the only valid means to this end. Both Drucker and Levitt’s insights form the philosophical substrate for JTBD, framing the product, system, or process not as an end in itself, but as a means to enable desired change in someone’s “real world”.

Modern JTBD: Ulwick, Christensen, and Theory Development

Tony Ulwick, after experiencing firsthand the failure of IBM’s PCjr product, launched a search to discover how organizations could systematically identify the outcomes customers (or process users) use to judge new offerings. Ulwick formalized jobs-as-process thinking, and by marrying Six Sigma concepts with innovation research, developed the “Outcome-Driven Innovation” (ODI) method, later shared with Clayton Christensen at Harvard.

Clayton Christensen, in his disruption theory research, sharpened the framing: customers don’t simply buy products—they “hire” them to get a job done, to make progress in their lives or work. He and Bob Moesta extended this to include the emotional and social dimensions of these jobs, and added nuance on how jobs can signal category-breaking opportunities for disruptive innovation. In essence, JTBD isn’t just about features; it’s about the outcome and the experience of progress.

The JTBD tool is now well-established in business, product development, health care, and increasingly, internal process improvement.

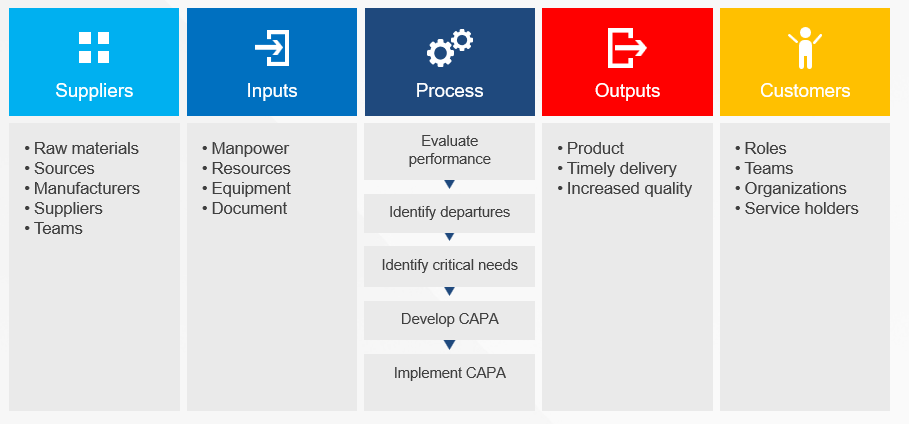

What Is a “Job” and How Does JTBD Actually Work?

Core Premise: The “Job” as the Real Center of Process Design

A “Job” in JTBD is not a task or activity—it is the progress someone seeks in a specific context. In regulated quality systems, this reframing prompts a pivotal question: For every step in the process, what is the user actually trying to achieve?

JTBD Statement Structure:

When [situation], I want to [job], so I can [desired outcome].

- “When a process deviation occurs, I want to quickly and accurately assess impact, so I can protect product quality without delaying production.”

- “When reviewing supplier audit responses, I want to identify meaningful risk signals, so I can challenge assumptions before they become failures.”

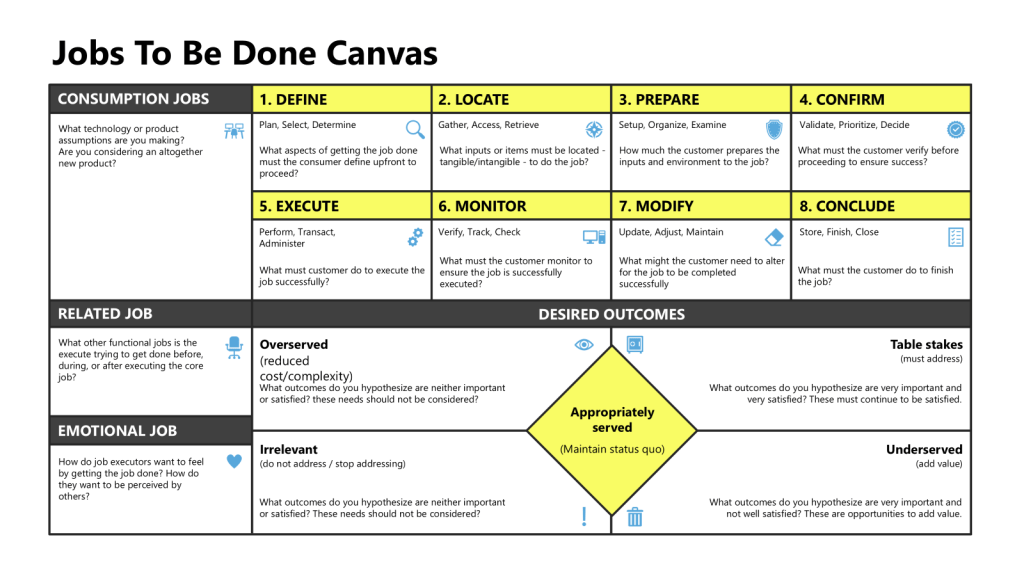

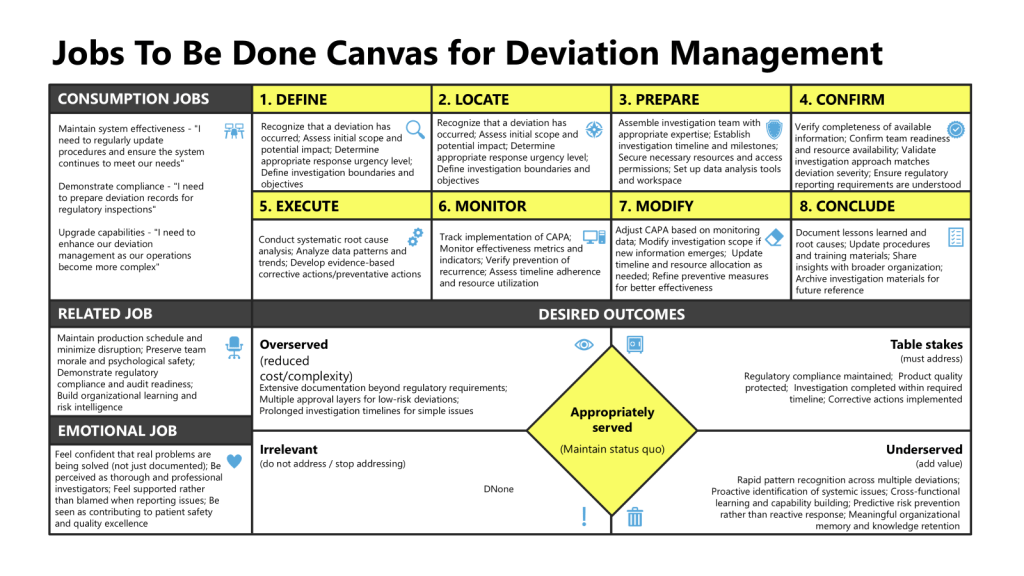

The Mechanics: Job Maps, Outcome Statements, and Dimensional Analysis

Job Map:

JTBD practitioners break the “job” down into a series of steps—the job map—outlining the user’s journey to achieve the desired progress. Ulwick’s “Universal Job Map” includes steps like: Define and plan, Locate inputs, Prepare, Confirm and validate, Execute, Monitor, Modify, and Conclude.

Dimension Analysis:

A full JTBD approach considers not only the functional needs (what must be accomplished), but also emotional (how users want to feel), social (how users want to appear), and cost (what users have to give up).

Outcome Statements:

JTBD expresses desired process outcomes in solution-agnostic language: To [achieve a specific goal], [user] must [perform action] to [produce a result].

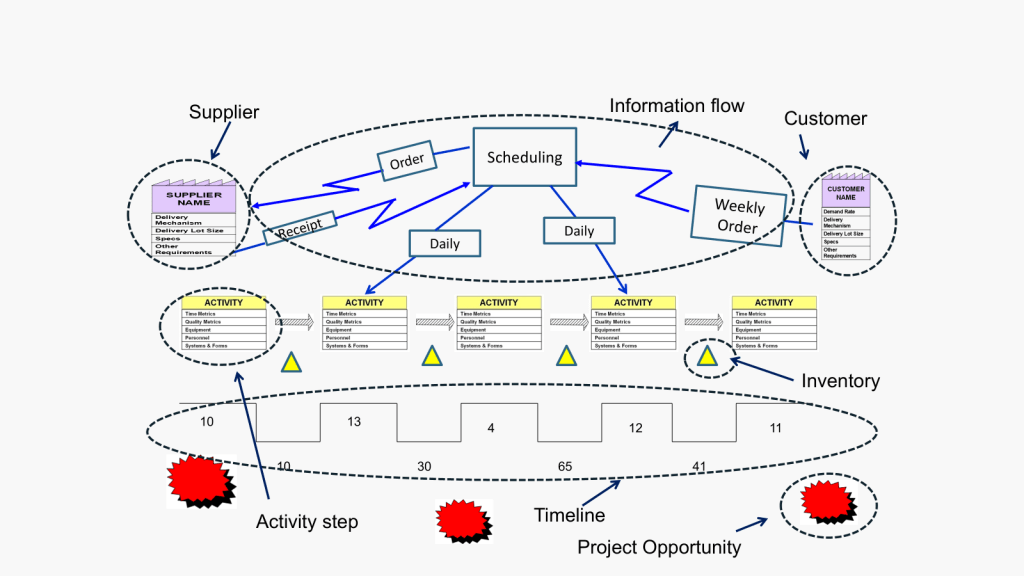

The Relationship Between Job Maps and Process Maps

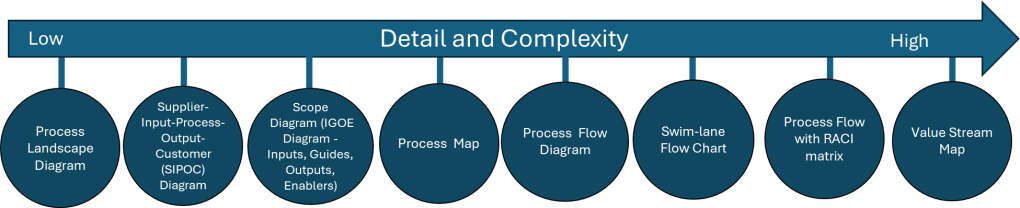

Job maps and process maps represent fundamentally different approaches to understanding and documenting work, despite both being visual tools that break down activities into sequential steps. Understanding their relationship reveals why each serves distinct purposes in organizational improvement efforts.

Core Distinction: Purpose vs. Execution

Job Maps focus on what customers or users are trying to accomplish—their desired outcomes and progress independent of any specific solution or current method. A job map asks: “What is the person fundamentally trying to achieve at each step?”

Process Maps focus on how work currently gets done—the specific activities, decisions, handoffs, and systems involved in executing a workflow. A process map asks: “What are the actual steps, roles, and systems involved in completing this work?”

Job Map Structure

Job maps follow a universal eight-step method regardless of industry or solution:

- Define – Determine goals and plan resources

- Locate – Gather required inputs and information

- Prepare – Set up the environment for execution

- Confirm – Verify readiness to proceed

- Execute – Carry out the core activity

- Monitor – Assess progress and performance

- Modify – Make adjustments as needed

- Conclude – Finish or prepare for repetition

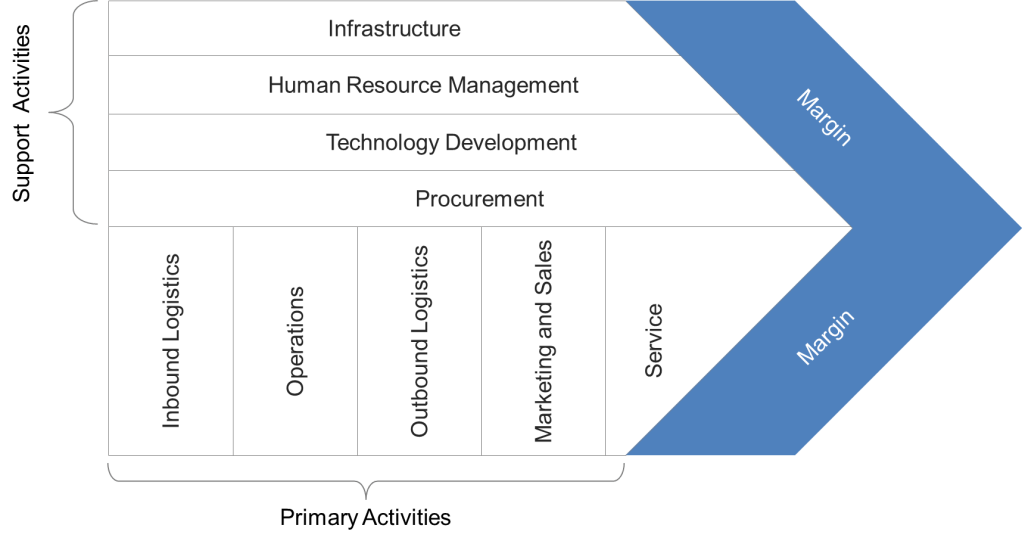

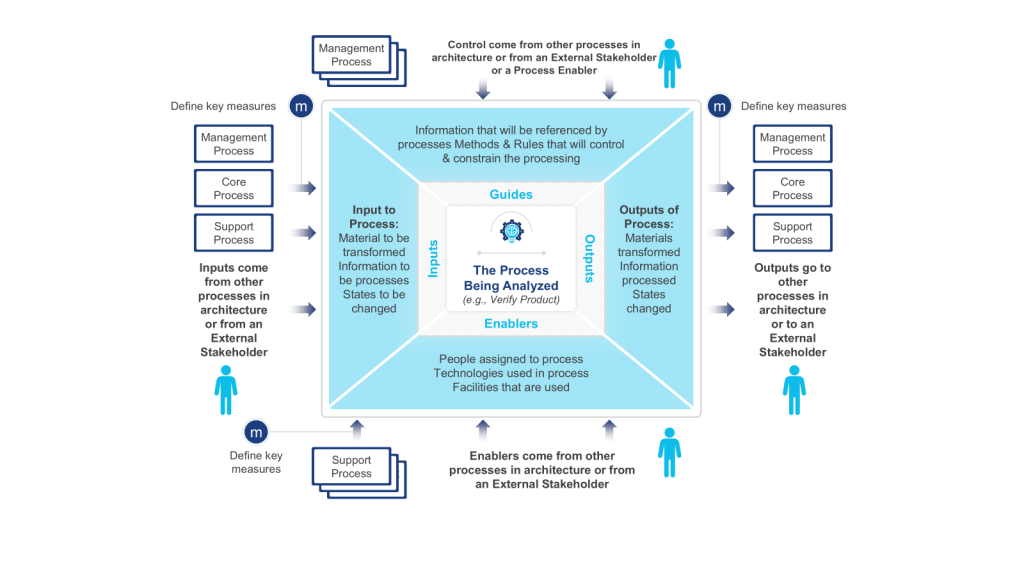

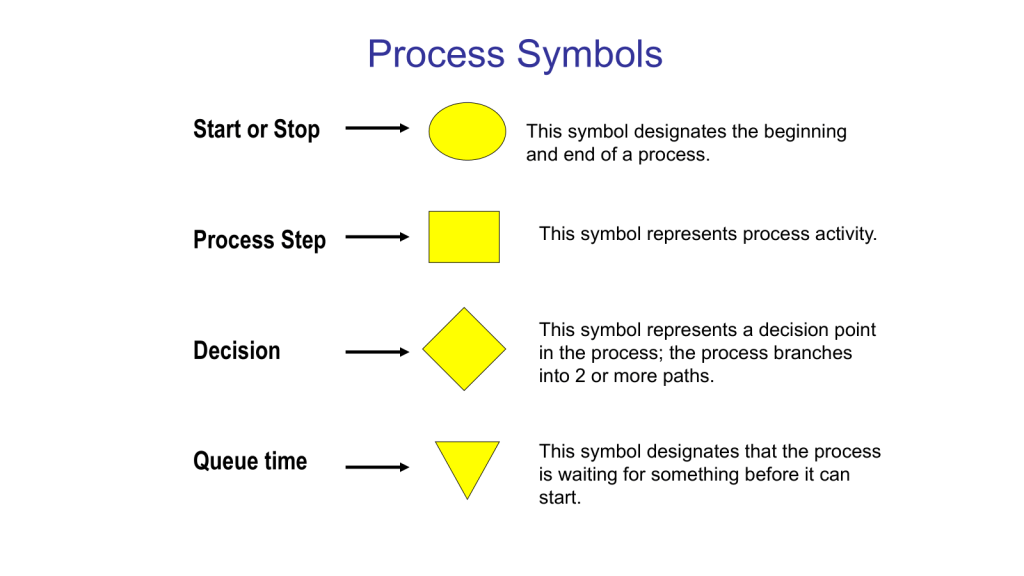

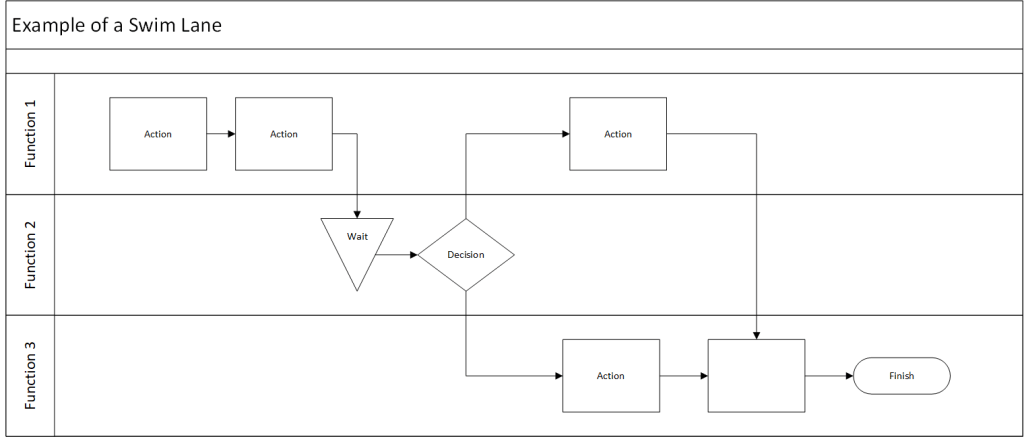

Process Map Structure

Process maps vary significantly based on the specific workflow being documented and typically include:

- Tasks and activities performed by different roles

- Decision points where choices affect the flow

- Handoffs between departments or systems

- Inputs and outputs at each step

- Time and resource requirements

- Exception handling and alternate paths

Perspective and Scope

Job Maps maintain a solution-agnostic perspective. We can actually get pretty close to universal industry job maps, because whatever approach an individual organization takes, the job map remains the same because it captures the underlying functional need, not the method of fulfillment. A job map starts an improvement effort, helping us understand what needs to exist.

Process Maps are solution-specific. They document exactly how a particular organization, system, or workflow operates, including specific tools, roles, and procedures currently in use. The process map defines what is, and is an outcome of process improvement.

JTBD vs. Design Thinking, and Other Process Redesign Models

Most process improvement methodologies—including classic “design thinking”—center around incremental improvement, risk minimization, and stakeholder consensus. As previously critiqued , design thinking’s participatory workshops and empathy prototypes can often reinforce conservative bias, indirectly perpetuating the status quo. The tendency to interview, ideate, and choose the “least disruptive” option can perpetuate “GI Joe Fallacy”: knowing is not enough; action emerges only through challenged structures and direct engagement.

JTBD’s strength?

It demands that organizations reframe the purpose and metrics of every step and tool: not “How do we optimize this investigation template?”; but rather, “Does this investigation process help users make actual progress towards safer, more effective risk detection?” JTBD uncovers latent needs, both explicit and tacit, that design thinking’s post-it note workshops often fail to surface.

Why JTBD Is Invaluable for Process Design in Quality Systems

JTBD Enables Auditable Process Redesign

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, deviation management is a linchpin process—defining how organizations identify, document, investigate, and respond to events that depart from expected norms. Classic improvement initiatives target cycle time, documentation accuracy, or audit readiness. But JTBD pushes deeper.

Example JTBD Analysis for Deviations:

- Trigger: A deviation is detected.

- Job: “I want to report and contextualize the event accurately, so I can ensure an effective response without causing unnecessary disruption.”

- Desired Outcome: Minimized product quality risk, transparency of root causes, actionable learning, regulatory confidence.

By mapping out the jobs of different deviation process stakeholders—production staff, investigation leaders, quality approvers, regulatory auditors—organizations can surface unmet needs: e.g., “Accelerating cross-functional root cause analysis while maintaining unbiased investigation integrity”; “Helping frontline operators feel empowered rather than blamed for honest reporting”; “Ensuring remediation is prioritized and tracked.”

Revealing Hidden Friction and Underserved Needs

JTBD methodology surfaces both overt and tacit pain points, often ignored in traditional process audits:

- Operators “hire” process workarounds when formal documentation is slow or punitive.

- Investigators seek intuitive data access, not just fields for “root cause.”

- Approvers want clarity, not bureaucracy.

- Regulatory reviewers “hire” the deviation process to provide organizational intelligence—not just box-checking.

A JTBD-based diagnostic invariably shows where job performance is low, but process compliance is high—a warning sign of process myopia and risk blindness.

Practical JTBD for Deviation Management: Step-by-Step Example

Job Statement and Context Definition

Define user archetypes:

- Frontline Production Staff: “When a deviation occurs, I want a frictionless way to report it, so I can get support and feedback without being blamed.”

- Quality Investigator: “When reviewing deviations, I want accessible, chronological data so I can detect patterns and act swiftly before escalation.”

- Quality Leader: “When analyzing deviation trends, I want systemic insights that allow for proactive action—not just retrospection.”

Job Mapping: Stages of Deviation Lifecycle

- Trigger/Detection: Event recognition (pattern recognition)—often leveraging both explicit SOPs and staff tacit knowledge.

- Reporting: Document the event in a way that preserves context and allows for nuanced understanding.

- Assessment: Rapid triage—“Is this risk emergent or routine? Is there unseen connection to a larger trend?” “Does this impact the product?”

- Investigation: “Does the process allow multidisciplinary problem-solving, or does it force siloed closure? Are patterns shared across functions?”

- Remediation: Job statement: “I want assurance that action will prevent recurrence and create meaningful learning.”

- Closure and Learning Loop: “Does the process enable reflective practice and cognitive diversity—can feedback loops improve risk literacy?”

JTBD mapping reveals specific breakpoints: documentation systems that prioritize completeness over interpretability, investigation timelines that erode engagement, premature closure.

Outcome Statements for Metrics

Instead of “deviations closed on time,” measure:

- Number of deviations generating actionable cross-functional insights.

- Staff perception of process fairness and learning.

- Time to credible remediation vs. time to closure.

- Audit reviewer alignment with risk signals detected pre-close, not only post-mortem.

JTBD and the Apprenticeship Dividend: Pattern Recognition and Tacit Knowledge

JTBD, when deployed authentically, actively supports the development of deeper pattern recognition and tacit knowledge—qualities essential for risk resilience.

- Structured exposure programs ensure users “hire” the process to learn common and uncommon risks.

- Cognitive diversity teams ensures the job of “challenging assumptions” is not just theoretical.

- True process improvement emerges when the system supports practice, reflection, and mentoring—outcomes unmeasurable by conventional improvement metrics.

JTBD Limitations: Caveats and Critical Perspective

No methodology is infallible. JTBD is only as powerful as the organization’s willingness to confront uncomfortable truths and challenge compliance-driven inertia:

- Rigorous but Demanding: JTBD synthesis is non-“snackable” and lacks the pop-management immediacy of other tools.

- Action Over Awareness: Knowing the job to be done is not sufficient; structures must enable action.

- Regulatory Realities: Quality processes must satisfy regulatory standards, which are not always aligned with lived user experience. JTBD should inform, not override, compliance strategies.

- Skill and Culture: Successful use demands qualitative interviewing skill, genuine cross-functional buy-in, and a culture of psychological safety—conditions not easily created.

Despite these challenges, JTBD remains unmatched for surfacing hidden process failures, uncovering underserved needs, and catalyzing redesign where it matters most.

Breaking Through the Status Quo

Many organizations pride themselves on their calibration routines, investigation checklists, and digital documentation platforms. But the reality is that these systems are often “hired” not to create learning—but to check boxes, push responsibility, and sustain the illusion of control. This leads to risk blindess and organizations systematically make themselves vulnerable when process myopia replaces real learning – zemblanity.

JTBD’s foundational question—“What job are we hiring this process to do?”—is more than a strategic exercise. It is a countermeasure against stagnation and blindness. It insists on radical honesty, relentless engagement, and humility before the complexity of operational reality. For deviation management, JTBD is a tool not just for compliance, but for organizational resilience and quality excellence.

Quality leaders should invest in JTBD not as a “one more tool,” but as a philosophical commitment: a way to continually link theory to action, root cause to remediation, and process improvement to real progress. Only then will organizations break free of procedural conservatism, cure risk blindness, and build systems worthy of trust and regulatory confidence.