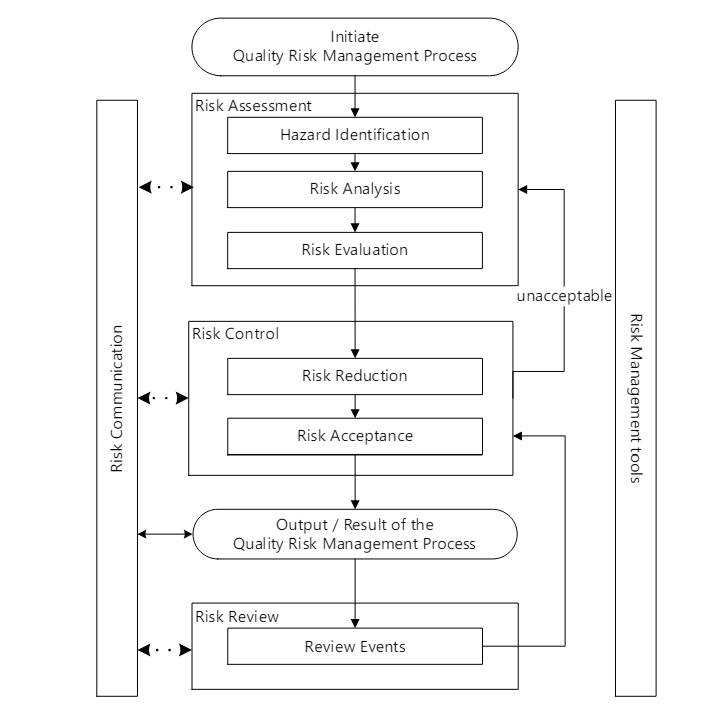

The revised ICH Q9 (R1) guideline shifts from “Risk Identification” to “Hazard Identification” to reflect a more precise approach to identifying potential sources of harm (hazards) rather than broadly identifying risks.

- Alignment with Risk Assessment Definition: The term “Hazard Identification” is more consistent with the established definition of Risk Assessment, which involves identifying hazards and analyzing and evaluating the associated risks.

- Clarity and Precision: By focusing on hazards, the guideline aims to improve the clarity and precision of the risk management process. This helps better understand and assess the potential harms associated with identified hazards, leading to more effective risk management.

- Improved Perception and Assessment: The change is expected to enhance how hazards are perceived and assessed, making the risk management process more robust and scientifically grounded. This is particularly important for ensuring patient safety and product quality.

- Consistency in Terminology: The revision aims to standardize the terminology used in quality risk management, reducing confusion and ensuring all stakeholders understand the terms and processes involved.

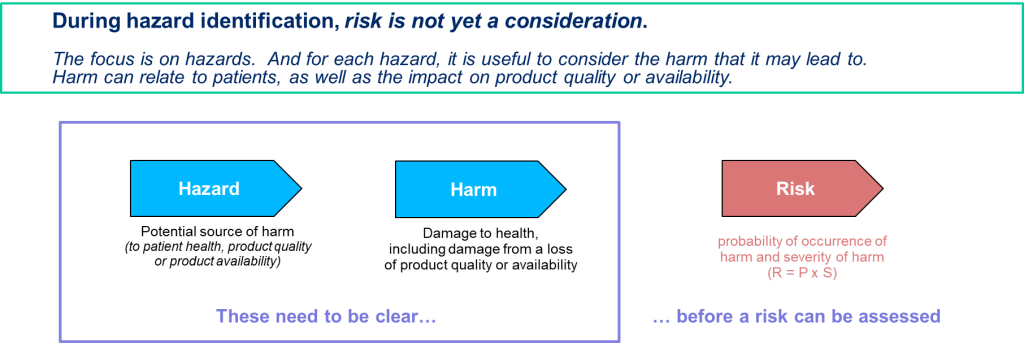

This small change in terminology can lead to better risk-based decisions by highlighting the need to identify hazards and not risks during the first step of the risk assessment process to remove any distractions about risks that may interfere with the hazard identification activity. When a Risk Assessment team focuses only on identifying hazards, they do not have to think about any related probabilities of occurrence – they only have to consider the potential hazards concerning the risk question under consideration. This is also the case of the severity of harm during hazard identification. There is no need to work to estimate the severity of the harm that may be presented by a hazard that comes later after the hazards have been identified.