Barriers, or controls, are one of the fundamental elements of root cause analysis. By understanding barriers—including their types and functions—we can understand both why a problem happened and how it can be prevented in the future. An evaluation of current process controls as part of root cause analysis can help determine whether all the current barriers pertaining to the problem you are investigating were present and effective.

Understanding Barrier Analysis

At its simplest, barrier analysis is a three-part brainstorm that examines the status and effectiveness of safety measures:

| Barrier Analysis |

|---|

| Barriers that failed |

| Barriers that were not used |

| Barriers that did not exist |

The key to this brainstorming session is to try to find all of the failed, unused, or nonexistent barriers. Do not be concerned if you are not certain which category they belong in initially.

Types of Barriers: Technical, Human, and Organizational

Most forms of barrier analysis examine two primary types: technical and administrative. Administrative barriers can be further broken down into “human” and “organizational” categories.

| Choose | Technical | Human | Organizational |

|---|---|---|---|

| If | A technical or engineering control exists | The control relies on a human reviewer or operator | The control involves a transfer of responsibility. For example, a document reviewed by both manufacturing and quality. |

| Examples | Separation among manufacturing or packaging lines Emergency power supply Dedicated equipment Barcoding Keypad controlled doors Separated storage for components Software that prevents a workflow from going further if a field is not completed Redundant designs | Training and certifications Use of checklist Verification of critical task by a second person | Clear procedures and policies Adequate supervision Adequate load of work Periodic process audits |

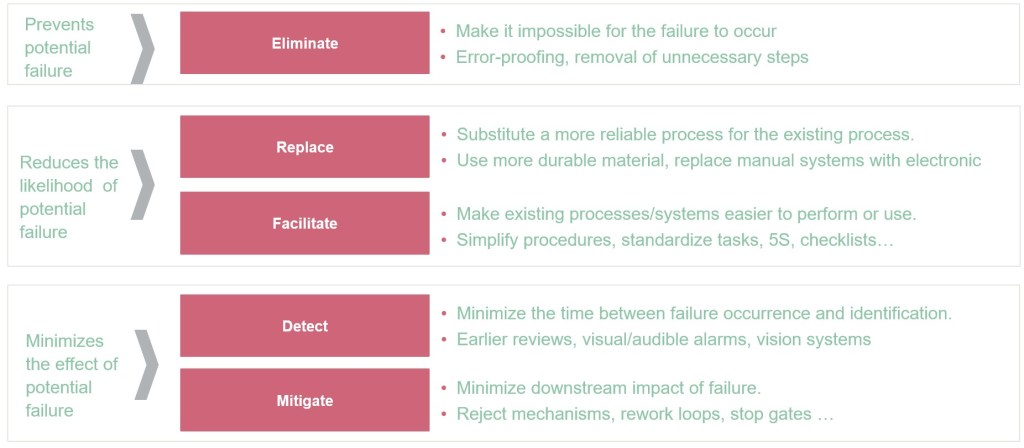

Preventive vs. Mitigative Barriers: A Critical Distinction

A fundamental aspect of barrier analysis involves understanding the difference between preventive and mitigative barriers. This distinction is crucial for comprehensive risk management and aligns with widely used frameworks such as bow-tie analysis.

Preventive Barriers

Preventive barriers are measures designed to prevent the top event from occurring. These barriers:

- Focus on stopping incidents before they happen

- Act as the first line of defense against threats

- Aim to reduce the likelihood that a risk will materialize

- Are proactive in nature, addressing potential causes before they can lead to unwanted events

Examples of preventive barriers include:

- Regular equipment maintenance programs

- Training and certification programs

- Access controls and authentication systems

- Equipment qualification protocols (IQ/OQ/PQ) validating proper installation and operation

Mitigative Barriers

Mitigative barriers are designed to reduce the impact and severity of consequences after the top event has occurred. These barriers:

- Focus on damage control rather than prevention

- Act to minimize harm when preventive measures have failed

- Reduce the severity or substantially decrease the likelihood of consequences occurring

- Are reactive in nature, coming into play after a risk has materialized

Examples of mitigative barriers include:

- Alarm systems and response procedures

- Containment measures for hazards

- Emergency response teams and protocols

- Backup power systems for critical operations

Timeline and Implementation Differences

The timing of barrier implementation and failure differs significantly between preventive and mitigative barriers:

- Preventive barriers often fail over days, weeks, or years before the top event occurs, providing more opportunities for identification and intervention

- Mitigative barriers often fail over minutes or hours after the top event occurs, requiring higher reliability and immediate effectiveness

- This timing difference leads to higher reliance on mitigative barriers working correctly the first time

Enhanced Barrier Analysis Framework

Building on the traditional three-part analysis, organizations should incorporate the preventive vs. mitigative distinction into their barrier evaluation:

| Enhanced Barrier Analysis |

|---|

| Preventive barriers that failed |

| Preventive barriers that were not used |

| Preventive barriers that did not exist |

| Mitigative barriers that failed |

| Mitigative barriers that were not used |

| Mitigative barriers that did not exist |

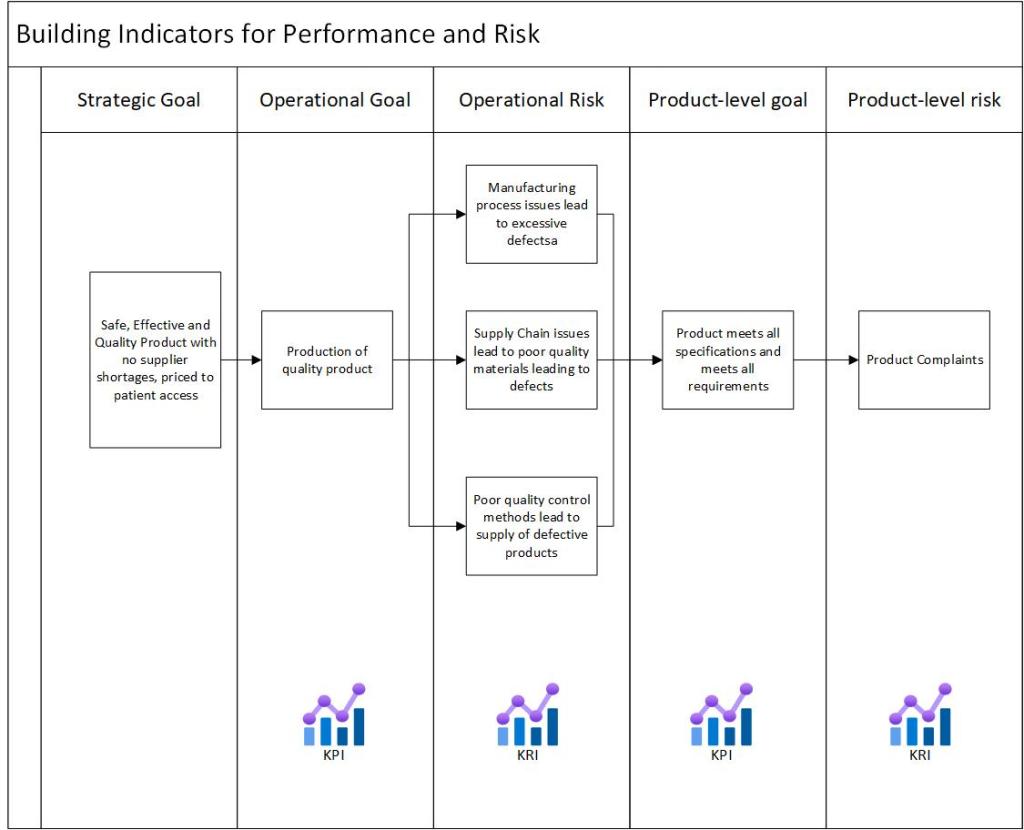

Integration with Risk Assessment

These barriers are the same as current controls in risk assessment, which is key in a wide variety of risk assessment tools. The optimal approach involves balancing both preventive and mitigative barriers without placing reliance on just one type. Some companies may favor prevention by placing high confidence in their systems and practices, while others may emphasize mitigation through reactive policies, but neither approach alone is advisable as they each result in over-reliance on one type of barrier.

Practical Application

When conducting barrier analysis as part of root cause investigation:

- Identify all relevant barriers that were supposed to protect against the incident

- Classify each barrier as preventive or mitigative based on its intended function

- Determine the barrier type: technical, human, or organizational

- Assess barrier status: failed, not used, or did not exist

- Evaluate the balance between preventive and mitigative measures

- Develop corrective actions that address gaps in both preventive and mitigative barriers

This comprehensive approach to barrier analysis provides a more nuanced understanding of how incidents occur and how they can be prevented or their consequences minimized in the future. By understanding both the preventive and mitigative functions of barriers, organizations can develop more robust risk management strategies that address threats at multiple points in the incident timeline.