The draft Annex 11 is a cultural shift, a new way of working that reaches beyond pure compliance to emphasize accountability, transparency, and full-system oversight. Section 5.1, simply titled: “Cooperation” is a small but might part of this transformation

On its face, Section 5.1 may sound like a pleasantry: the regulation states that “there should be close cooperation between all relevant personnel such as process owner, system owner, qualified persons and IT.” In reality, this is a direct call to action for the formation of empowered, cross-functional, and highly integrated governance structures. It’s a recognition that, in an era when computerized systems underpin everything from batch release to deviation investigation, a siloed or transactional approach to system ownership is organizational malpractice.

Governance: From Siloed Ownership to Shared Accountability

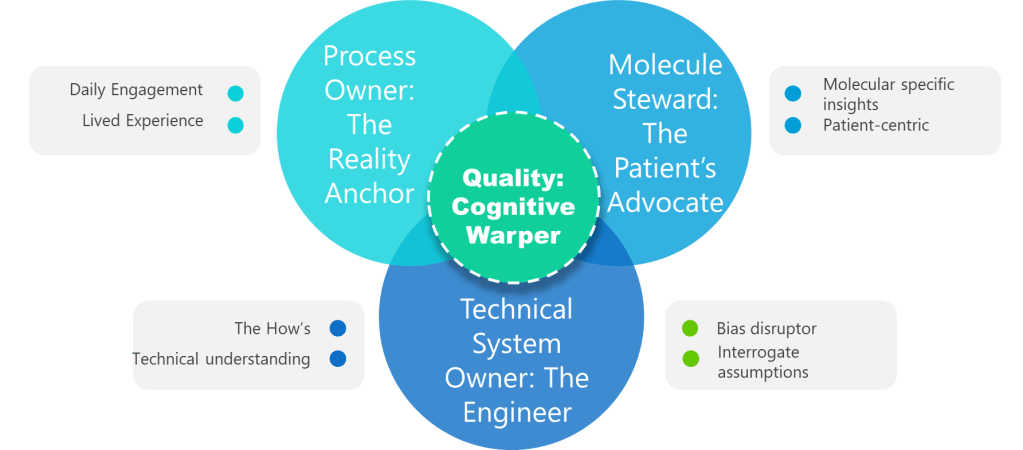

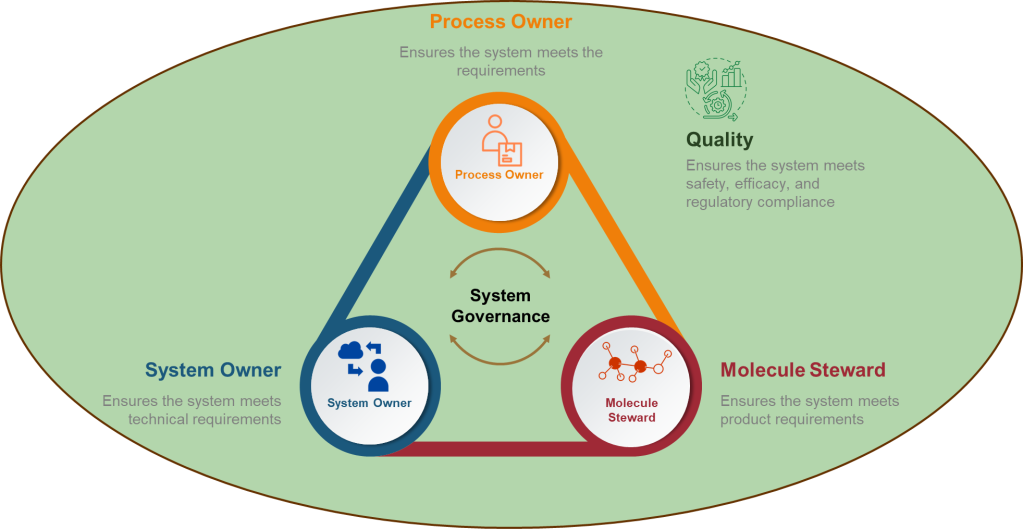

Let’s breakdown what “cooperation” truly means in the current pharmaceutical digital landscape. Governance in the Annex 11 context is no longer a paperwork obligation but the backbone for digital trust. The roles of Process Owner (who understands the GMP-critical process), System Owner (managing the integrity and availability of the system), Quality (bearing regulatory release or oversight risk), and the IT function (delivering the technical and cybersecurity expertise) all must be clearly defined, actively engaged, and jointly responsible for compliance outcomes.

This shared ownership translates directly into how organizations structure project teams. Legacy models—where IT “owns the system,” Quality “owns compliance,” and business users “just use the tool”—are explicitly outdated. Section 5.1 obligates that these domains work in seamless partnership, not simply at “handover” moments but throughout every lifecycle phase from selection and implementation to maintenance and retirement. Each group brings indispensable knowledge: the process owner knows process risks and requirements; the system owner manages configuration and operational sustainability; Quality interprets regulatory standards and ensure release integrity; IT enables security, continuity, and technical change.

Practical Project Realities: Embedding Cooperation in Every Phase

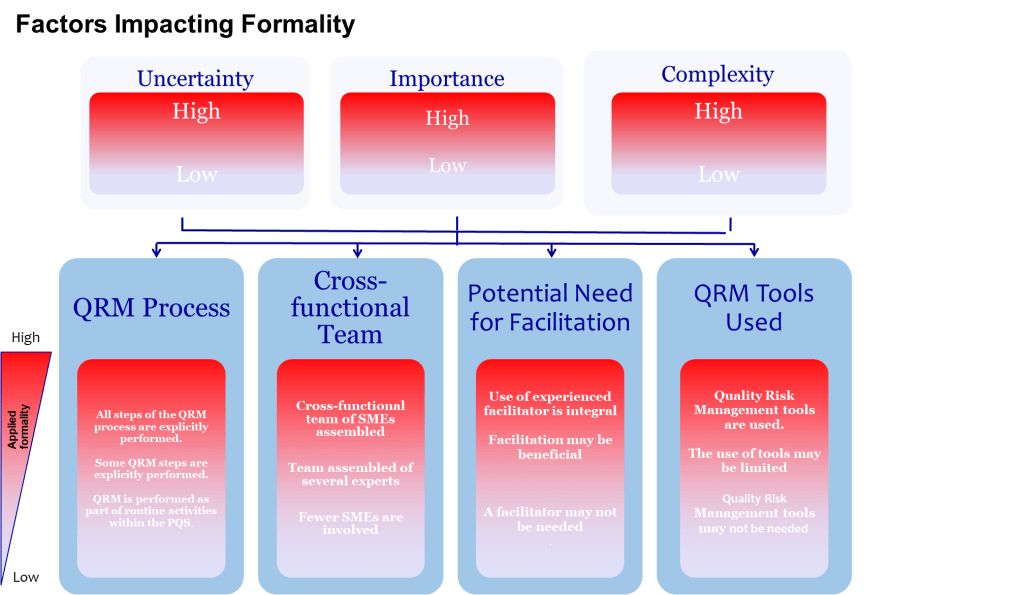

In my experience, the biggest compliance failures often do not hinge on technical platform choices, but on fractured or missing cross-functional cooperation. Robust governance, under Section 5.1, doesn’t just mean having an org chart—it means everyone understands and fulfills their operational and compliance obligations every day. In practice, this requires formal documents (RACI matrices, governance charters), clear escalation routes, and regular—preferably, structured—forums for project and system performance review.

During system implementation, deep cooperation means all stakeholders are involved in requirements gathering and risk assessment, not just as “signatories” but as active contributors. It is not enough for the business to hand off requirements to IT with minimal dialogue, nor for IT to configure a system and expect the Qulity sign-off at the end. Instead, expect joint workshops, shared risk assessments (tying from process hazard analysis to technical configuration), and iterative reviews where each stakeholder is empowered to raise objections or demand proof of controls.

At all times, communication must be systematic, not ad hoc: regular governance meetings, with pre-published minutes and action tracking; dashboards or portals where issues, risks, and enhancement requests can be logged, tracked, and addressed; and shared access to documentation, validation reports, CAPA records, and system audit trails. This is particularly crucial as digital systems (cloud-based, SaaS, hybrid) increasingly blur the lines between “IT” and “business” roles.

Training, Qualifications, and Role Clarity: Everyone Is Accountable

Section 5.1 further clarifies that relevant personnel—regardless of functional home—must possess the appropriate qualifications, documented access rights, and clearly defined responsibilities. This raises the bar on both onboarding and continuing education. “Cooperation” thus demands rotational training and knowledge-sharing among core team members. Process owners must understand enough of IT and validation to foresee configuration-related compliance risks. IT staff must be fluent in GMP requirements and data integrity. Quality must move beyond audit response and actively participate in system configuration choices, validation planning, and periodic review.

In my own project experience, the difference between a successful, inspection-ready implementation and a troubled, remediation-prone rollout is almost always the presence, or absence, of this cross-trained, truly cooperative project team.

Supplier and Service Provider Partnerships: Extending Governance Beyond the Walls

The rise of cloud, SaaS, and outsourced system management means that “cooperation” extends outside traditional organizational boundaries. Section 5.1 works in concert with supplier sections of Annex 11—everyone from IT support to critical SaaS vendors must be engaged as partners within the governance framework. This requires clear, enforceable contracts outlining roles and responsibilities for security, data integrity, backup, and business continuity. It also means periodic supplier reviews, joint planning sessions, and supplier participation in incidents and change management when systems span organizations.

Internal IT must also be treated with the same rigor—a department supporting a GMP system is, under regulation, no different than a third-party vendor; it must be a named party in the cooperation and governance ecosystem.

Oversight and Monitoring: Governance as a Living Process

Effective cooperation isn’t a “set and forget”—it requires active, joint oversight. That means frequent management reviews (not just at system launch but periodically throughout the lifecycle), candid CAPA root cause debriefs across teams, and ongoing risk and performance evaluations done collectively. Each member of the governance body—be they system owner, process owner, or Quality—should have the right to escalate issues and trigger review of system configuration, validation status, or supplier contracts.

Structured communication frameworks—regularly scheduled project or operations reviews, joint documentation updates, and cross-functional risk and performance dashboards—turn this principle into practice. This is how validation, data integrity, and operational performance are confidently sustained (not just checked once) in a rigorous, documented, and inspection-ready fashion.

The “Cooperation” Imperative and the Digital GMP Transformation

With the explosion of digital complexity—artificial intelligence, platform integrations, distributed teams—the management of computerized systems has evolved well beyond technical mastery or GMP box-ticking. True compliance, under the new Annex 11, hangs on the ability of organizations to operationalize interdisciplinary governance. Section 5.1 thus becomes a proxy for digital maturity: teams that still operate in silos or treat “cooperation” as a formality will be missed by the first regulatory deep dive or major incident.

Meanwhile, sites that embed clear role assignment, foster cross-disciplinary partnership, and create active, transparent governance processes (documented and tracked) will find not only that inspections run smoothly—they’ll spend less time in audit firefighting, make faster decisions during technology rollouts, and spot improvement opportunities early.

Teams that embrace the cooperation mandate see risk mitigation, continuous improvement, and regulatory trust as the natural byproducts of shared accountability. Those that don’t will find themselves either in chronic remediation or watching more agile, digitally mature competitors pull ahead.

Key Governance and Project Team Implications

To provide a summary for project, governance, and operational leaders, here is a table distilling the new paradigm:

| Governance Aspect | Implications for Project & Governance Teams |

|---|---|

| Clear Role Assignment | Define and document responsibilities for process owners, system owners, and IT. |

| Cross-Functional Partnership | Ensure collaboration among quality, IT, validation, and operational teams. |

| Training & Qualification | Clarify required qualifications, access levels, and competencies for personnel. |

| Supplier Oversight | Establish contracts with roles, responsibilities, and audit access rights. |

| Proactive Monitoring | Maintain joint oversight mechanisms to promptly address issues and changes. |

| Communication Framework | Set up regular, documented interaction channels among involved stakeholders. |

In this new landscape, “cooperation” is not a regulatory afterthought. It is the hinge on which the entire digital validation and integrity culture swings. How and how well your teams work together is now as much a matter of inspection and business success as any technical control, risk assessment, or test script.