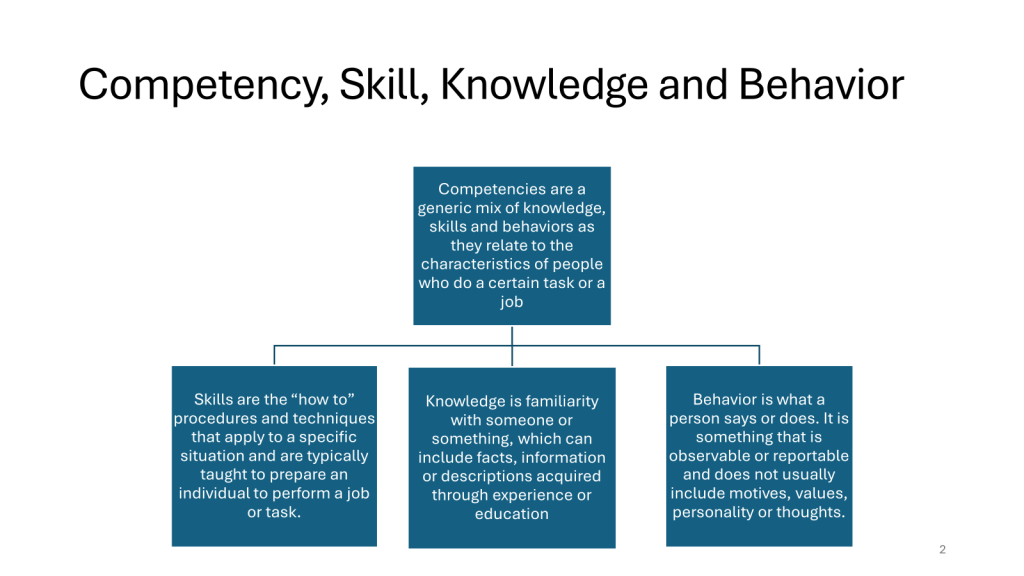

When someone asks about your skills they are often fishing for the wrong information. They want to know about your certifications, your knowledge of regulations, your understanding of methodologies, or your familiarity with industry frameworks. These questions barely scratch the surface of actual competence.

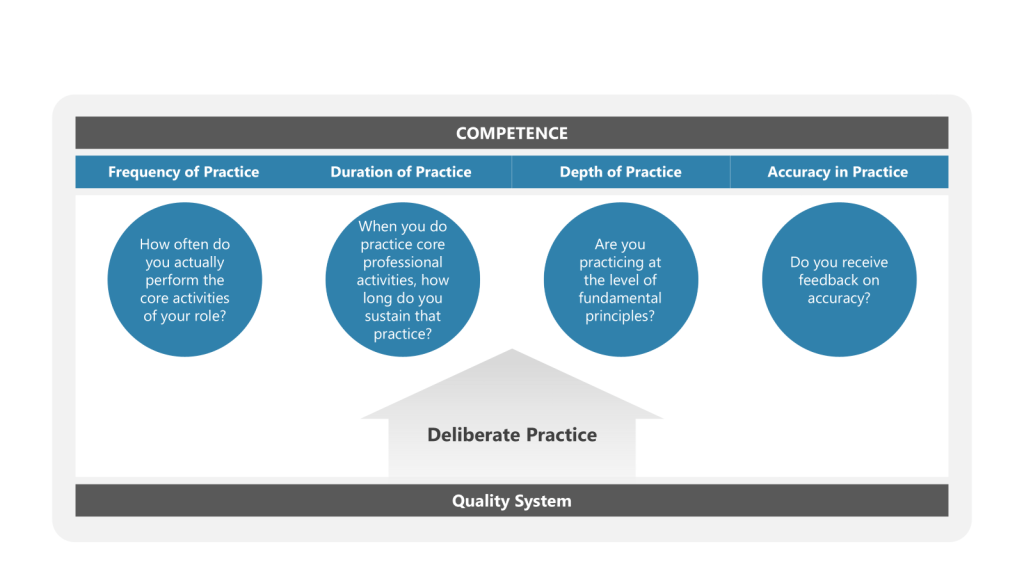

The real questions that matter are deceptively simple: What is your frequency of practice? What is your duration of practice? What is your depth of practice? What is your accuracy in practice?

Because here’s the uncomfortable truth that most professionals refuse to acknowledge: if you don’t practice a skill, competence doesn’t just stagnate—it actively degrades.

The Illusion of Permanent Competency

We persist in treating professional expertise like riding a bicycle, “once learned, never forgotten”. This fundamental misunderstanding pervades every industry and undermines the very foundation of what it means to be competent.

Research consistently demonstrates that technical skills begin degrading within weeks of initial training. In medical education, procedural skills show statistically significant decline between six and twelve weeks without practice. For complex cognitive skills like risk assessment, data analysis, and strategic thinking, the degradation curve is even steeper.

A meta-analysis examining skill retention found that half of initial skill acquisition performance gains were lost after approximately 6.5 months for accuracy-based tasks, 13 months for speed-based tasks, and 11 months for mixed performance measures. Yet most professionals encounter meaningful opportunities to practice their core competencies quarterly at best, often less frequently.

Consider the data analyst who completed advanced statistical modeling training eighteen months ago but hasn’t built a meaningful predictive model since. How confident should we be in their ability to identify data quality issues or select appropriate analytical techniques? How sharp are their skills in interpreting complex statistical outputs?

The answer should make us profoundly uncomfortable.

The Four Dimensions of Competence

True competence in any professional domain operates across four critical dimensions that most skill assessments completely ignore:

Frequency of Practice

How often do you actually perform the core activities of your role, not just review them or discuss them, but genuinely work through the systematic processes that define expertise?

This infrequency creates competence gaps that compound over time. Skills that aren’t regularly exercised atrophy, leading to oversimplified problem-solving, missed critical considerations, and inadequate solution strategies. The cognitive demands of sophisticated professional work—considering multiple variables simultaneously, recognizing complex patterns, making nuanced judgments—require regular engagement to maintain proficiency.

Deliberate practice research shows that experts practice longer sessions (87.90 minutes) compared to amateurs (46.00 minutes). But more importantly, they practice regularly. The frequency component isn’t just about total hours—it’s about consistent, repeated exposure to challenging scenarios that push the boundaries of current capability.

Duration of Practice

When you do practice core professional activities, how long do you sustain that practice? Minutes? Hours? Days?

Brief, superficial engagement with complex professional activities doesn’t build or maintain competence. Most work activities in professional environments are fragmented, interrupted by meetings, emails, and urgent issues. This fragmentation prevents the deep, sustained practice necessary to maintain sophisticated capabilities.

Research on deliberate practice emphasizes that meaningful skill development requires focused attention on activities designed to improve performance, typically lasting 1-3 practice sessions to master specific sub-skills. But maintaining existing expertise requires different duration patterns—sustained engagement with increasingly complex scenarios over extended periods.

Depth of Practice

Are you practicing at the surface level—checking boxes and following templates—or engaging with the fundamental principles that drive effective professional performance?

Shallow practice reinforces mediocrity. Deep practice—working through novel scenarios, challenging existing methodologies, grappling with uncertain outcomes—builds robust competence that can adapt to evolving challenges.

The distinction between deliberate practice and generic practice is crucial. Deliberate practice involves:

- Working on skills that require 1-3 practice sessions to master specific components

- Receiving expert feedback on performance

- Pushing beyond current comfort zones

- Focusing on areas of weakness rather than strengths

Most professionals default to practicing what they already do well, avoiding the cognitive discomfort of working at the edge of their capabilities.

Accuracy in Practice

When you practice professional skills, do you receive feedback on accuracy? Do you know when your analyses are incomplete, your strategies inadequate, or your evaluation criteria insufficient?

Without accurate feedback mechanisms, practice can actually reinforce poor techniques and flawed reasoning. Many professionals practice in isolation, never receiving objective assessment of their work quality or decision-making effectiveness.

Research on medical expertise reveals that self-assessment accuracy has two critical components: calibration (overall performance prediction) and resolution (relative strengths and weaknesses identification). Most professionals are poor at both, leading to persistent blind spots and competence decay that remains hidden until critical failures expose it.

The Knowledge-Practice Disconnect

Professional training programs focus almost exclusively on knowledge transfer—explaining concepts, demonstrating tools, providing frameworks. They ignore the practice component entirely, creating professionals who can discuss methodologies eloquently but struggle to execute them competently when complexity increases.

Knowledge is static. Practice is dynamic.

Professional competence requires pattern recognition developed through repeated exposure to diverse scenarios, decision-making capabilities honed through continuous application, and judgment refined through ongoing experience with outcomes. These capabilities can only be developed and maintained through deliberate, sustained practice.

A study of competency assessment found that deliberate practice hours predicted only 26% of skill variation in games like chess, 21% for music, and 18% for sports. The remaining variance comes from factors like age of initial exposure, genetics, and quality of feedback—but practice remains the single most controllable factor in competence development.

The Competence Decay Crisis

Industries across the board face a hidden crisis: widespread competence decay among professionals who maintain the appearance of expertise while losing the practiced capabilities necessary for effective performance.

This crisis manifests in several ways:

- Templated Problem-Solving: Professionals rely increasingly on standardized approaches and previous solutions, avoiding the cognitive challenge of systematic evaluation. This approach may satisfy requirements superficially while missing critical issues that don’t fit established patterns.

- Delayed Problem Recognition: Degraded assessment skills lead to longer detection times for complex issues and emerging problems. Issues that experienced, practiced professionals would identify quickly remain hidden until they escalate to significant failures.

- Inadequate Solution Strategies: Without regular practice in developing and evaluating approaches, professionals default to generic solutions that may not address specific problem characteristics effectively. The result is increased residual risk and reduced system effectiveness.

- Reduced Innovation: Competence decay stifles innovation in professional approaches. Professionals with degraded skills retreat to familiar, comfortable methodologies rather than exploring more effective techniques or adapting to emerging challenges.

The Skill Decay Research

The phenomenon of skill decay is well-documented across domains. Research shows that skills requiring complex mental requirements, difficult time limits, or significant motor control have an overwhelming likelihood of being completely lost after six months without practice.

Key findings from skill decay research include:

- Retention interval: The longer the period of non-use, the greater the probability of decay

- Overlearning: Extra training beyond basic competency significantly improves retention

- Task complexity: More complex skills decay faster than simple ones

- Feedback quality: Skills practiced with high-quality feedback show better retention

A practical framework divides skills into three circles based on practice frequency:

- Circle 1: Daily-use skills (slowest decay)

- Circle 2: Weekly/monthly-use skills (moderate decay)

- Circle 3: Rare-use skills (rapid decay)

Most professionals’ core competencies fall into Circle 2 or 3, making them highly vulnerable to decay without systematic practice programs.

Building Practice-Based Competence

Addressing the competence decay crisis requires fundamental changes in how individuals and organizations approach professional skill development and maintenance:

Implement Regular Practice Requirements

Professionals must establish mandatory practice requirements for themselves—not training sessions or knowledge refreshers, but actual practice with real or realistic professional challenges. This practice should occur monthly, not annually.

Consider implementing practice scenarios that mirror the complexity of actual professional challenges: multi-variable analyses, novel technology evaluations, integrated problem-solving exercises. These scenarios should require sustained engagement over days or weeks, not hours.

Create Feedback-Rich Practice Environments

Effective practice requires accurate, timely feedback. Professionals need mechanisms for evaluating work quality and receiving specific, actionable guidance for improvement. This might involve peer review processes, expert consultation programs, or structured self-assessment tools.

The goal isn’t criticism but calibration—helping professionals understand the difference between adequate and excellent performance and providing pathways for continuous improvement.

Measure Practice Dimensions

Track the four dimensions of practice systematically: frequency, duration, depth, and accuracy. Develop personal metrics that capture practice engagement quality, not just training completion or knowledge retention.

These metrics should inform professional development planning, resource allocation decisions, and competence assessment processes. They provide objective data for identifying practice gaps before they become performance problems.

Integrate Practice with Career Development

Make practice depth and consistency key factors in advancement decisions and professional reputation building. Professionals who maintain high-quality, regular practice should advance faster than those who rely solely on accumulated experience or theoretical knowledge.

This integration creates incentives for sustained practice engagement while signaling commitment to practice-based competence development.

The Assessment Revolution

The next time someone asks about your professional skills, here’s what you should tell them:

“I practice systematic problem-solving every month, working through complex scenarios for two to four hours at a stretch. I engage deeply with the fundamental principles, not just procedural compliance. I receive regular feedback on my work quality and continuously refine my approach based on outcomes and expert guidance.”

If you can’t make that statement honestly, you don’t have professional skills—you have professional knowledge. And in the unforgiving environment of modern business, that knowledge won’t be enough.

Better Assessment Questions

Instead of asking “What do you know about X?” or “What’s your experience with Y?”, we should ask:

- Frequency: “When did you last perform this type of analysis/assessment/evaluation? How often do you do this work?”

- Duration: “How long did your most recent project of this type take? How much sustained focus time was required?”

- Depth: “What was the most challenging aspect you encountered? How did you handle uncertainty?”

- Accuracy: “What feedback did you receive? How did you verify the quality of your work?”

These questions reveal the difference between knowledge and competence, between experience and expertise.

The Practice Imperative

Professional competence cannot be achieved or maintained without deliberate, sustained practice. The stakes are too high and the environments too complex to rely on knowledge alone.

The industry’s future depends on professionals who understand the difference between knowing and practicing, and organizations willing to invest in practice-based competence development.

Because without practice, even the most sophisticated frameworks become elaborate exercises in compliance theater—impressive in appearance, inadequate in substance, and ultimately ineffective at achieving the outcomes that stakeholders depend on our competence to deliver.

The choice is clear: embrace the discipline of deliberate practice or accept the inevitable decay of the competence that defines professional value. In a world where complexity is increasing and stakes are rising, there’s really no choice at all.

Building Deliberate Practice into the Quality System

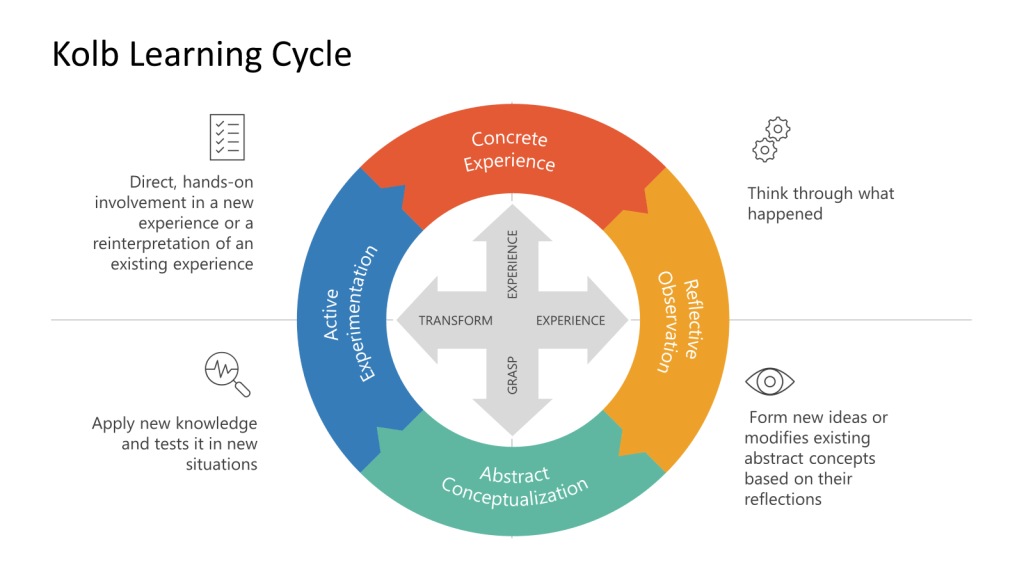

Embedding genuine practice into a quality system demands more than mandating periodic training sessions or distributing updated SOPs. The reality is that competence in GxP environments is not achieved by passive absorption of information or box-checking through e-learning modules. Instead, you must create a framework where deliberate, structured practice is interwoven with day-to-day operations, ongoing oversight, and organizational development.

Start by reimagining training not as a singular event but as a continuous cycle that mirrors the rhythms of actual work. New skills—whether in deviation investigation, GMP auditing, or sterile manufacturing technique—should be introduced through hands-on scenarios that reflect the ambiguity and complexity found on the shop floor or in the laboratory. Rather than simply reading procedures or listening to lectures, trainees should regularly take part in simulation exercises that challenge them to make decisions, justify their logic, and recognize pitfalls. These activities should involve increasingly nuanced scenarios, moving beyond basic compliance errors to the challenging grey areas that usually trip up experienced staff.

To cement these experiences as genuine practice, integrate assessment and reflection into the learning loop. Every critical quality skill—from risk assessment to change control—should be regularly practiced, not just reviewed. Root cause investigation, for instance, should be a recurring workshop, where both new hires and seasoned professionals work through recent, anonymized cases as a team. After each practice session, feedback should be systematic, specific, and forward-looking, highlighting not just mistakes but patterns and habits that can be addressed in the next cycle. The aim is to turn every training into a diagnostic tool for both the individual and the organization: What is being retained? Where does accuracy falter? Which aspects of practice are deep, and which are still superficial?

Crucially, these opportunities for practice must be protected from routine disruptions. If practice sessions are routinely canceled for “higher priority” work, or if their content is superficial, their effectiveness collapses. Commit to building practice into annual training matrices alongside regulatory requirements, linking participation and demonstrated competence with career progression criteria, bonus structures, or other forms of meaningful recognition.

Finally, link practice-based training with your quality metrics and management review. Use not just completion data, but outcome measures—such as reduction in repeat deviations, improved audit readiness, or enhanced error detection rates—to validate the impact of the practice model. This closes the loop, driving both ongoing improvement and organizational buy-in.

A quality system rooted in practice demands investment and discipline, but the result is transformative: professionals who can act, not just recite; an organization that innovates and adapts under pressure; and a compliance posture that is both robust and sustainable, because it’s grounded in real, repeatable competence.