We often try to solve problems as if we are outside them. When people describe a problem you will see them pointing away from themselves – you hear the word “them” a lot. “They” are seen as the problem. However, truly hard problems are system problems, and if you are part of the system (hint – you are) then you are part of the problem.

Being inside the problem means we have to understand bias and our blind spots – both as individuals, as teams and as organizations.

Understanding our blind spots

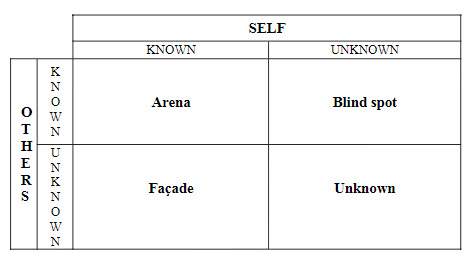

An easy tool to start thinking about this is the Johari window, a technique that helps people better understand their relationship with themselves and others. There are two axis, others and self. This forms four quadrants:

- Arena – What is known by both self and others. It is also often referred to as the Public Area.

- Blind spot – This region deals with knowledge unknown to self but visible to others, such as shortcomings or annoying habits.

- Façade – This includes the features and knowledge of the individual which are not known to others. I prefer when this is called the Hidden. It was originally called facade because it can include stuff that is untrue but for the individual’s claim.

- Unknown – The characteristics of the person that are unknown to both self and others.

An example of a basic Johari Window (my own) can be found here.

Users are advised to reduce the area of ‘blind spot’ and ‘unknown’, while expand the ‘arena’. The premise is that the lesser the hidden personality, the better the person becomes in relating with other people.

The use of Johari Window is popular among business coaches as a cognitive tool to understand intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships. There isn’t much value of this tool as an empirical framework and it hasn’t held up to academic rigor. Still, like many such things it can bring to light the central point that we need to understand our hidden biases.

Another good tool to start understanding biases is a personal audit.

Using the Johari Window for Teams

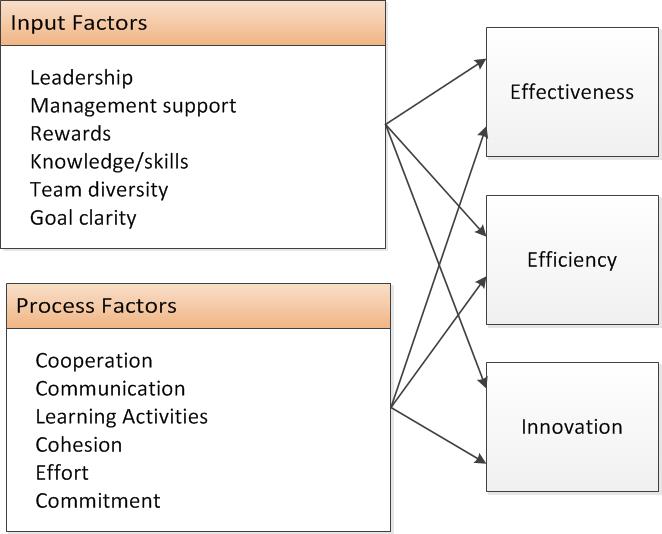

Teams and organizations have blind spots, think of them as negative input factors or as procedural negatives.

The Johari Window can also be applied to knowledge transparency, and it fits nicely to the concepts of tacit and explicit knowledge bringing to light knowledge-seeking and knowledge-sharing behavior. For example, the ‘arena’ can simply become the ‘unknown’ if there is no demand or offer pertaining to the knowledge to be occupied by the recipient or to be shared by the owner, respectively.

The Johari Window transforms with the the four quadrants changing to:

- Arena – What the organization knows it knows. Contains knowledge available to the team as well as related organizations. Realizing such improvements is usually demanded by network partners and should be priority for implementation.

- Façade – What the organization does know it knows. Knowledge that is only available to parts of the focal organization. Derived improvements are unexpected, but beneficial for the organization and its collaborations.

- Blind Spot – What the organization knows it does not know. Knowledge only available to other organizations – internal and external. This area should be investigated with highest priority, to benefit from insights and to maintain effectiveness.

- Unknown – What the organization does not know it does not know, and what the organization believes it knows but does not actually know. Knowledge about opportunities for improvement that is not available to anyone. Its identification leads to the Façade sector.

We are firmly in the land of uncertainty, ignorance and surprise, and we are starting to perform a risk based approach to our organization blind spots. At the heart, knowledge management, problem solving and risk management are all very closely intertwined.