The strategic utilization of supplier documentation in qualification processes presents a significant opportunity to enhance efficiency while maintaining strict quality standards. Determining what supplier documentation can be accepted and what aspects require additional qualification is critical for streamlining validation activities without compromising product quality or patient safety.

Regulatory Framework Supporting Supplier Documentation Use

Regulatory bodies increasingly recognize the value of leveraging third-party documentation when properly evaluated and integrated into qualification programs. The FDA’s 2011 Process Validation Guidance embraces risk-based approaches that focus resources on critical aspects rather than duplicating standard testing. This guidance references the ASTM E2500 standard, which explicitly addresses the use of supplier documentation in qualification activities.

The EU GMP Annex 15 provides clear regulatory support, stating: “Data supporting qualification and/or validation studies which were obtained from sources outside of the manufacturers own programmes may be used provided that this approach has been justified and that there is adequate assurance that controls were in place throughout the acquisition of such data.” This statement offers a regulatory pathway for incorporating supplier documentation, provided proper controls and justification exist.

ICH Q9 further supports this approach by encouraging risk-based allocation of resources, allowing companies to focus qualification efforts on areas of highest risk while leveraging supplier documentation for well-controlled, lower-risk aspects. The integration of these regulatory perspectives creates a framework that enables efficient qualification strategies while maintaining regulatory compliance.

Benefits of Utilizing Supplier Documentation in Qualification

Biotech manufacturing systems present unique challenges due to their complexity, specialized nature, and biological processes. Leveraging supplier documentation offers multiple advantages in this context:

- Supplier expertise in specialized biotech equipment often exceeds that available within pharmaceutical companies. This expertise encompasses deep understanding of complex technologies such as bioreactors, chromatography systems, and filtration platforms that represent years of development and refinement. Manufacturers of bioprocess equipment typically employ specialists who design and test equipment under controlled conditions unavailable to end users.

- Integration of engineering documentation into qualification protocols can reduce project timelines, while significantly decreasing costs associated with redundant testing. This efficiency is particularly valuable in biotech, where manufacturing systems frequently incorporate numerous integrated components from different suppliers.

- By focusing qualification resources on truly critical aspects rather than duplicating standard supplier testing, organizations can direct expertise toward product-specific challenges and integration issues unique to their manufacturing environment. This enables deeper verification of critical aspects that directly impact product quality rather than dispersing resources across standard equipment functionality tests.

Criteria for Acceptable Supplier Documentation

Audit of the Supplier

Supplier Quality System Assessment

Before accepting any supplier documentation, a thorough assessment of the supplier’s quality system must be conducted. This assessment should evaluate the following specific elements:

- Quality management systems certification to relevant standards with verification of certification scope and validity. This should include review of recent certification audit reports and any major findings.

- Document control systems that demonstrate proper version control, appropriate approvals, secure storage, and systematic review and update cycles. Specific attention should be paid to engineering document management systems and change control procedures for technical documentation.

- Training programs with documented evidence of personnel qualification, including training matrices showing alignment between job functions and required training. Training records should demonstrate both initial training and periodic refresher training, particularly for personnel involved in critical testing activities.

- Change control processes with formal impact assessments, appropriate review levels, and implementation verification. These processes should specifically address how changes to equipment design, software, or testing protocols are managed and documented.

- Deviation management systems with documented root cause analysis, corrective and preventive actions, and effectiveness verification. The system should demonstrate formal investigation of testing anomalies and resolution of identified issues prior to completion of supplier testing.

- Test equipment calibration and maintenance programs with NIST-traceable standards, appropriate calibration frequencies, and out-of-tolerance investigations. Records should demonstrate that all test equipment used in generating qualification data was properly calibrated at the time of testing.

- Software validation practices aligned with GAMP5 principles, including risk-based validation approaches for any computer systems used in equipment testing or data management. This should include validation documentation for any automated test equipment or data acquisition systems.

- Internal audit processes with independent auditors, documented findings, and demonstrable follow-up actions. Evidence should exist that the supplier conducts regular internal quality audits of departments involved in equipment design, manufacturing, and testing.

Technical Capability Verification

Supplier technical capability must be verified through:

- Documentation of relevant experience with similar biotech systems, including a portfolio of comparable projects successfully completed. This should include reference installations at regulated pharmaceutical or biotech companies with complexity similar to the proposed equipment.

- Technical expertise of key personnel demonstrated through formal qualifications, industry experience, and specific expertise in biotech applications. Review should include CVs of key personnel who will be involved in equipment design, testing, and documentation.

- Testing methodologies that incorporate scientific principles, appropriate statistics, and risk-based approaches. Documentation should demonstrate test method development with sound scientific rationales and appropriate controls.

- Calibrated and qualified test equipment with documented measurement uncertainties appropriate for the parameters being measured. This includes verification that measurement capabilities exceed the required precision for critical parameters by an appropriate margin.

- GMP understanding demonstrated through documented training, experience in regulated environments, and alignment of test protocols with GMP principles. Personnel should demonstrate awareness of regulatory requirements specific to biotech applications.

- Measurement traceability to national standards with documented calibration chains for all critical measurements. This should include identification of reference standards used and their calibration status.

- Design control processes aligned with recognized standards including design input review, risk analysis, design verification, and design validation. Design history files should be available for review to verify systematic development approaches.

Documentation Quality Requirements

Acceptable supplier documentation must demonstrate:

- Creation under GMP-compliant conditions with evidence of training for personnel generating the documentation. Records should demonstrate that personnel had appropriate training in documentation practices and understood the criticality of accurate data recording.

- Compliance with GMP documentation practices including contemporaneous recording, no backdating, proper error correction, and use of permanent records. Documents should be reviewed for evidence of proper data recording practices such as signed and dated entries, proper correction of errors, and absence of unexplained gaps.

- Completeness with clearly defined acceptance criteria established prior to testing. Pre-approved protocols should define all test parameters, conditions, and acceptance criteria without post-testing modifications.

- Actual test results rather than summary statements, with raw data supporting reported values. Testing documentation should include actual measured values, not just pass/fail determinations, and should provide sufficient detail to allow independent evaluation.

- Deviation records with thorough investigations and appropriate resolutions. Any testing anomalies should be documented with formal investigations, root cause analysis, and justification for any retesting or data exclusion.

- Traceability to requirements through clear linkage between test procedures and equipment specifications. Each test should reference the specific requirement or specification it is designed to verify.

- Authorization by responsible personnel with appropriate signatures and dates. Documents should demonstrate review and approval by qualified individuals with defined responsibilities in the testing process.

- Data integrity controls including audit trails for electronic data, validated computer systems, and measures to prevent unauthorized modification. Evidence should exist that data security measures were in place during testing and documentation generation.

- Statistical analysis and justification where appropriate, particularly for performance data involving multiple measurements or test runs. Where sampling is used, justification for sample size and statistical power should be provided.

Good Engineering Practice (GEP) Implementation

The supplier must demonstrate application of Good Engineering Practice through:

- Adherence to established industry standards and design codes relevant to biotech equipment. This includes documentation citing specific standards applied during design and evidence of compliance verification.

- Implementation of systematic design methodologies including requirements gathering, conceptual design, detailed design, and design review phases. Design documentation should demonstrate progression through formal design stages with appropriate approvals at each stage.

- Application of appropriate testing protocols based on equipment type, criticality, and intended use. Testing strategies should be aligned with industry norms for similar equipment and demonstrate appropriate rigor.

- Maintenance of equipment calibration throughout testing phases with records demonstrating calibration status. All test equipment should be documented as calibrated before and after critical testing activities.

- Documentation accuracy and completeness demonstrated through systematic review processes and quality checks. Evidence should exist of multiple review levels for critical documentation and formal approval processes.

- Implementation of appropriate commissioning procedures aligned with recognized industry practices. Commissioning plans should demonstrate systematic verification of all equipment functions and utilities.

- Formal knowledge transfer processes ensuring proper communication between design, manufacturing, and qualification teams. Evidence should exist of structured handover meetings or documentation between project phases.

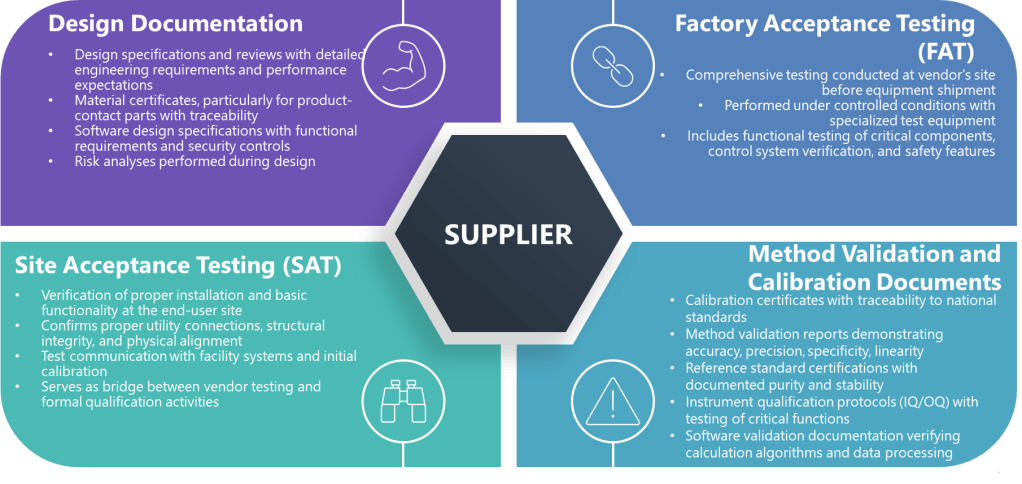

Types of Supplier Documentation That Can Be Leveraged

When the above criteria are met, the following specific types of supplier documentation can potentially be leveraged.

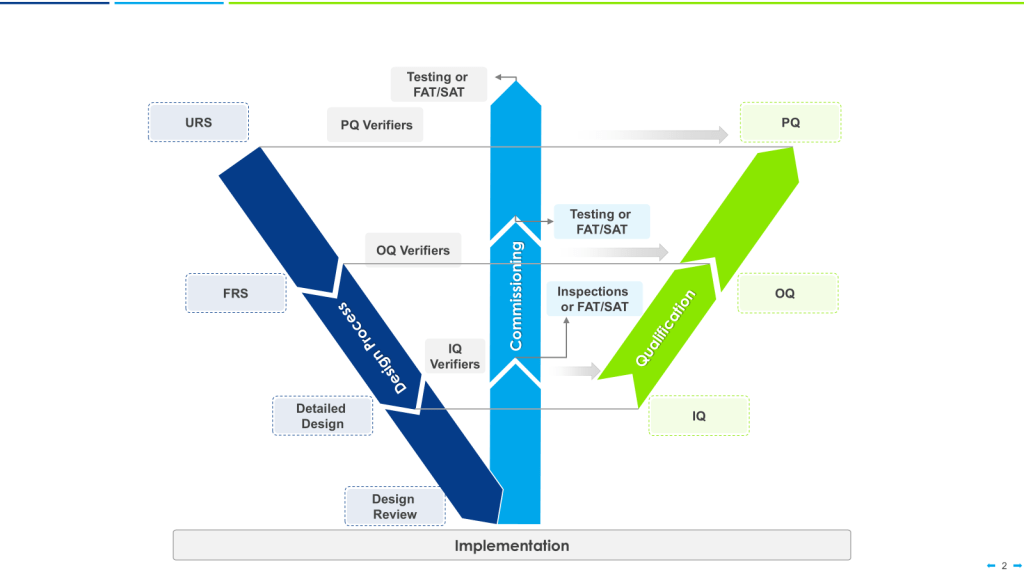

Factory Acceptance Testing (FAT)

FAT documentation represents comprehensive testing at the supplier’s site before equipment shipment. These documents are particularly valuable because they often represent testing under more controlled conditions than possible at the installation site. For biotech applications, FAT documentation may include:

- Functional testing of critical components with detailed test procedures, actual measurements, and predetermined acceptance criteria. This should include verification of all critical operating parameters under various operating conditions.

- Control system verification through systematic testing of all control loops, alarms, and safety interlocks. Testing should demonstrate proper response to normal operating conditions as well as fault scenarios.

- Material compatibility confirmation with certificates of conformance for product-contact materials and testing to verify absence of leachables or extractables that could impact product quality.

- Cleaning system performance verification through spray pattern testing, coverage verification, and drainage evaluation. For CIP (Clean-in-Place) systems, this should include documented evidence of cleaning effectiveness.

- Performance verification under load conditions that simulate actual production requirements, with test loads approximating actual product characteristics where possible.

- Alarm and safety feature testing with verification of proper operation of all safety interlocks, emergency stops, and containment features critical to product quality and operator safety.

- Software functionality testing with documented verification of all user requirements related to automation, control systems, and data management capabilities.

Site Acceptance Testing (SAT)

SAT documentation verifies proper installation and basic functionality at the end-user site. For biotech equipment, this might include:

- Installation verification confirming proper utilities connections, structural integrity, and physical alignment according to engineering specifications. This should include verification of spatial requirements and accessibility for operation and maintenance.

- Basic functionality testing demonstrating that all primary equipment functions operate as designed after transportation and installation. Tests should verify that no damage occurred during shipping and installation.

- Communication with facility systems verification, including integration with building management systems, data historians, and centralized control systems. Testing should confirm proper data transfer and command execution between systems.

- Initial calibration verification for all critical instruments and control elements, with documented evidence of calibration accuracy and stability.

- Software configuration verification showing proper installation of control software, correct parameter settings, and appropriate security configurations.

- Environmental conditions verification confirming that the installed location meets requirements for temperature, humidity, vibration, and other environmental factors that could impact equipment performance.

Design Documentation

Design documents that can support qualification include:

- Design specifications with detailed engineering requirements, operating parameters, and performance expectations. These should include rationales for critical design decisions and risk assessments supporting design choices.

- Material certificates, particularly for product-contact parts, with full traceability to raw material sources and manufacturing processes. Documentation should include testing for biocompatibility where applicable.

- Software design specifications with detailed functional requirements, system architecture, and security controls. These should demonstrate structured development approaches with appropriate verification activities.

- Risk analyses performed during design, including FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis) or similar systematic evaluations of potential failure modes and their impacts on product quality and safety.

- Design reviews and approvals with documented participation of subject matter experts across relevant disciplines including engineering, quality, manufacturing, and validation.

- Finite element analysis reports or other engineering studies supporting critical design aspects such as pressure boundaries, mixing efficiency, or temperature distribution.

Method Validation and Calibration Documents

For analytical instruments and measurement systems, supplier documentation might include:

- Calibration certificates with traceability to national standards, documented measurement uncertainties, and verification of calibration accuracy across the operating range.

- Method validation reports demonstrating accuracy, precision, specificity, linearity, and robustness for analytical methods intended for use with the equipment.

- Reference standard certifications with documented purity, stability, and traceability to compendial standards where applicable.

- Instrument qualification protocols (IQ/OQ) with comprehensive testing of all critical functions and performance parameters against predetermined acceptance criteria.

- Software validation documentation showing systematic verification of all calculation algorithms, data processing functions, and reporting capabilities.

What Must Still Be Qualified By The End User

Despite the value of supplier documentation, certain aspects always require direct qualification by the end user. These areas should be the focus of end-user qualification activities:

Site-Specific Integration

Site-specific integration aspects requiring end-user qualification include:

- Facility utility connections and performance verification under actual operating conditions. This must include verification that utilities (water, steam, gases, electricity) meet the required specifications at the point of use, not just at the utility generation source.

- Integration with other manufacturing systems, particularly verification of interfaces between equipment from different suppliers. Testing should verify proper data exchange, sequence control, and coordinated operation during normal production and exception scenarios.

- Facility-specific environmental conditions including temperature mapping, particulate monitoring, and pressure differentials that could impact biotech processes. Testing should verify that environmental conditions remain within acceptable limits during worst-case operating scenarios.

- Network connectivity and data transfer verification, including security controls, backup systems, and disaster recovery capabilities. Testing should demonstrate reliable performance under peak load conditions and proper handling of network interruptions.

- Alarm systems integration with central monitoring and response protocols, including verification of proper notification pathways and escalation procedures. Testing should confirm appropriate alarm prioritization and notification of responsible personnel.

- Building management system interfaces with verification of environmental monitoring and control capabilities critical to product quality. Testing should verify proper feedback control and response to excursions.

Process-Specific Requirements

Process-specific requirements requiring end-user qualification include:

- Process-specific parameters beyond standard equipment functionality, with testing under actual operating conditions using representative materials. Testing should verify equipment performance with actual process materials, not just test substances.

- Custom configurations for specific products, including verification of specialized equipment settings, program parameters, or mechanical adjustments unique to the user’s products.

- Production-scale performance verification, with particular attention to scale-dependent parameters such as mixing efficiency, heat transfer, and mass transfer. Testing should verify that performance characteristics demonstrated at supplier facilities translate to full-scale production.

- Process-specific cleaning verification, including worst-case residue removal studies and cleaning cycle development specific to the user’s products. Testing should demonstrate effective cleaning of all product-contact surfaces with actual product residues.

- Specific operating ranges for the user’s process, with verification of performance at the extremes of normal operating parameters. Testing should verify capability to maintain critical parameters within required tolerances throughout production cycles.

- Process-specific automation sequences and recipes with verification of all production scenarios, including exception handling and recovery procedures. Testing should verify all process recipes and automated sequences with actual production materials.

- Hold time verification for intermediate process steps specific to the user’s manufacturing process. Testing should confirm product stability during maximum expected hold times between process steps.

Critical Quality Attributes

Testing related directly to product-specific critical quality attributes should generally not be delegated solely to supplier documentation, particularly for:

- Bioburden and endotoxin control verification using the actual production process and materials. Testing should verify absence of microbial contamination and endotoxin introduction throughout the manufacturing process.

- Product contact material compatibility studies with the specific products and materials used in production. Testing should verify absence of leachables, extractables, or product degradation due to contact with equipment surfaces.

- Product-specific recovery rates and process yields based on actual production experience. Testing should verify consistency of product recovery across multiple batches and operating conditions.

- Process-specific impurity profiles with verification that equipment design and operation do not introduce or magnify impurities. Testing should confirm that impurity clearance mechanisms function as expected with actual production materials.

- Sterility assurance measures specific to the user’s aseptic processing approaches. Testing should verify the effectiveness of sterilization methods and aseptic techniques with the actual equipment configuration and operating procedures.

- Product stability during processing with verification that equipment operation does not negatively impact critical quality attributes. Testing should confirm that product quality parameters remain within acceptable limits throughout the manufacturing process.

- Process-specific viral clearance capacity for biological manufacturing processes. Testing should verify effective viral removal or inactivation capabilities with the specific operating parameters used in production.

Operational and Procedural Integration

A critical area often overlooked in qualification plans is operational and procedural integration, which requires end-user qualification for:

- Operator interface verification with confirmation that user interactions with equipment controls are intuitive, error-resistant, and aligned with standard operating procedures. Testing should verify that operators can effectively control the equipment under normal and exception conditions.

- Procedural workflow integration ensuring that equipment operation aligns with established manufacturing procedures and documentation systems. Testing should verify compatibility between equipment operation and procedural requirements.

- Training effectiveness verification for operators, maintenance personnel, and quality oversight staff. Assessment should confirm that personnel can effectively operate, maintain, and monitor equipment in compliance with established procedures.

- Maintenance accessibility and procedural verification to ensure that preventive maintenance can be performed effectively without compromising product quality. Testing should verify that maintenance activities can be performed as specified in supplier documentation.

- Sampling accessibility and technique verification to ensure representative samples can be obtained safely without compromising product quality. Testing should confirm that sampling points are accessible and provide representative samples.

- Change management procedures specific to the user’s quality system, with verification that equipment changes can be properly evaluated, implemented, and documented. Testing should confirm integration with the user’s change control system.

Implementing a Risk-Based Approach to Supplier Documentation

A systematic risk-based approach should be implemented to determine what supplier documentation can be leveraged and what requires additional verification:

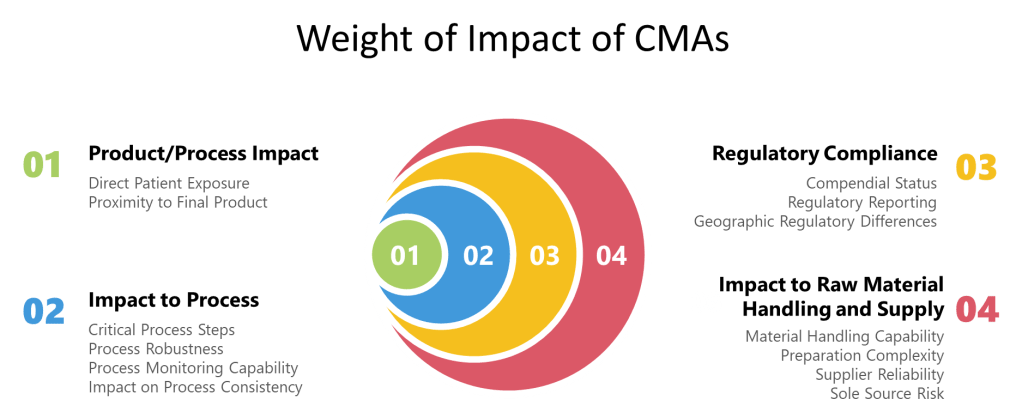

- Perform impact assessment to categorize system components based on their potential impact on product quality:

- Direct impact components with immediate influence on critical quality attributes

- Indirect impact components that support direct impact systems

- No impact components without reasonable influence on product quality

- Conduct risk analysis using formal tools such as FMEA to identify:

- Critical components and functions requiring thorough qualification

- Potential failure modes and their consequences

- Existing controls that mitigate identified risks

- Residual risks requiring additional qualification activities

- Develop a traceability matrix linking:

- User requirements to functional specifications

- Functional specifications to design elements

- Design elements to testing activities

- Testing activities to specific documentation

- Identify gaps between supplier documentation and qualification requirements by:

- Mapping supplier testing to user requirements

- Evaluating the quality and completeness of supplier testing

- Identifying areas where supplier testing does not address user-specific requirements

- Assessing the reliability and applicability of supplier data to the user’s specific application

- Create targeted verification plans to address:

- High-risk areas not adequately covered by supplier documentation

- User-specific requirements not addressed in supplier testing

- Integration points between supplier equipment and user systems

- Process-specific performance requirements

This risk-based methodology ensures that qualification resources are focused on areas of highest concern while leveraging reliable supplier documentation for well-controlled aspects.

Documentation and Justification Requirements

When using supplier documentation in qualification, proper documentation and justification are essential:

- Create a formal supplier assessment report documenting:

- Evaluation methodology and criteria used to assess the supplier

- Evidence of supplier quality system effectiveness

- Verification of supplier technical capabilities

- Assessment of documentation quality and completeness

- Identification of any deficiencies and their resolution

- Develop a gap assessment identifying:

- Areas where supplier documentation meets qualification requirements

- Areas requiring additional end-user verification

- Rationale for decisions on accepting or supplementing supplier documentation

- Risk-based justification for the scope of end-user qualification activities

- Prepare a traceability matrix showing:

- Mapping between user requirements and testing activities

- Source of verification for each requirement (supplier or end-user testing)

- Evidence of test completion and acceptance

- Cross-references to specific documentation supporting requirement verification

- Maintain formal acceptance of supplier documentation with:

- Quality unit review and approval of supplier documentation

- Documentation of any additional verification activities performed

- Records of any deficiencies identified and their resolution

- Evidence of conformance to predetermined acceptance criteria

- Document rationale for accepting supplier documentation:

- Risk-based justification for leveraging supplier testing

- Assessment of supplier documentation reliability and completeness

- Evaluation of supplier testing conditions and their applicability

- Scientific rationale supporting acceptance decisions

- Ensure document control through:

- Formal incorporation of supplier documentation into the quality system

- Version control and change management for supplier documentation

- Secure storage and retrieval systems for qualification records

- Maintenance of complete documentation packages supporting qualification decisions

Biotech-Specific Considerations

For Cell Culture Systems:

While basic temperature, pressure, and mixing capabilities may be verified through supplier testing, product-specific parameters require end-user verification. These include:

- Cell viability and growth characteristics with the specific cell lines used in production. End-user testing should verify consistent cell growth, viability, and productivity under normal operating conditions.

- Metabolic profiles and nutrient consumption rates specific to the production process. Testing should confirm that equipment design supports appropriate nutrient delivery and waste removal for optimal cell performance.

- Homogeneity studies for bioreactors under process-specific conditions including actual media formulations, cell densities, and production phase operating parameters. Testing should verify uniform conditions throughout the bioreactor volume during all production phases.

- Cell culture monitoring systems calibration and performance with actual production cell lines and media. Testing should confirm reliable and accurate monitoring of critical culture parameters throughout the production cycle.

- Scale-up effects specific to the user’s cell culture process, with verification that performance characteristics demonstrated at smaller scales translate to production scale. Testing should verify comparable cell growth kinetics and product quality across scales.

For Purification Systems

Chromatography system pressure capabilities and gradient formation may be accepted from supplier testing, but product-specific performance requires end-user verification:

- Product-specific recovery, impurity clearance, and yield verification using actual production materials. Testing should confirm consistent product recovery and impurity removal across multiple cycles.

- Resin lifetime and performance stability with the specific products and buffer systems used in production. Testing should verify consistent performance throughout the expected resin lifetime.

- Cleaning and sanitization effectiveness specific to the user’s products and contaminants. Testing should confirm complete removal of product residues and effective sanitization between production cycles.

- Column packing reproducibility and performance with production-scale columns and actual resins. Testing should verify consistent column performance across multiple packing cycles.

- Buffer preparation and delivery system performance with actual buffer formulations. Testing should confirm accurate preparation and delivery of all process buffers under production conditions.

For Analytical Methods

Basic instrument functionality can be verified through supplier IQ/OQ documentation, but method-specific performance requires end-user verification:

- Method-specific performance with actual product samples, including verification of specificity, accuracy, and precision with the user’s products. Testing should confirm reliable analytical performance with actual production materials.

- Method robustness under the specific laboratory conditions where testing will be performed. Testing should verify consistent method performance across the range of expected operating conditions.

- Method suitability for the intended use, including capability to detect relevant product variants and impurities. Testing should confirm that the method can reliably distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable product quality.

- Operator technique verification to ensure consistent method execution by all analysts who will perform the testing. Assessment should confirm that all analysts can execute the method with acceptable precision and accuracy.

- Data processing and reporting verification with the user’s specific laboratory information management systems. Testing should confirm accurate data transfer, calculations, and reporting.

Practical Examples

Example 1: Bioreactor Qualification

For a 2000L bioreactor system, supplier documentation might be leveraged for:

Acceptable with minimal verification: Pressure vessel certification, welding documentation, motor specification verification, basic control system functionality, standard safety features. These aspects are governed by well-established engineering standards and can be reliably verified by the supplier in a controlled environment.

Acceptable with targeted verification: Temperature control system performance, basic mixing capability, sensor calibration procedures. While these aspects can be largely verified by the supplier, targeted verification in the user’s facility ensures that performance meets process-specific requirements.

Requiring end-user qualification: Process-specific mixing studies with actual media, cell culture growth performance, specific gas transfer rates, cleaning validation with product residues. These aspects are highly dependent on the specific process and materials used and cannot be adequately verified by the supplier.

In all cases, the acceptance of supplier documentation must be documented well and performed according to GMPs and at appropriately described in the Validation Plan or other appropriate testing rationale document.

Example 2: Chromatography System Qualification

For a multi-column chromatography system, supplier documentation might be leveraged as follows:

Acceptable with minimal verification: Pressure testing of flow paths, pump performance specifications, UV detector linearity, conductivity sensor calibration, valve switching accuracy. These aspects involve standard equipment functionality that can be reliably verified by the supplier using standardized testing protocols.

Acceptable with targeted verification: Gradient formation accuracy, column switching precision, UV detection sensitivity with representative proteins, system cleaning procedures. These aspects require verification with materials similar to those used in production but can largely be addressed through supplier testing with appropriate controls.

Requiring end-user qualification: Product-specific binding capacity, elution conditions optimization, product recovery rates, impurity clearance, resin lifetime with actual process streams, cleaning validation with actual product residues. These aspects are highly process-specific and require testing with actual production materials under normal operating conditions.

The qualification approach must balance efficiency with appropriate rigor, focusing end-user testing on aspects that are process-specific or critical to product quality.

Example 3: Automated Analytical Testing System Qualification

For an automated high-throughput analytical testing platform used for product release testing, supplier documentation might be leveraged as follows:

Acceptable with minimal verification: Mechanical subsystem functionality, basic software functionality, standard instrument calibration, electrical safety features, standard data backup systems. These fundamental aspects of system performance can be reliably verified by the supplier using standardized testing protocols.

Acceptable with targeted verification: Sample throughput rates, basic method execution, standard curve generation, basic system suitability testing, data export functions. These aspects require verification with representative materials but can largely be addressed through supplier testing with appropriate controls.

Requiring end-user qualification: Method-specific performance with actual product samples, detection of product-specific impurities, method robustness under laboratory-specific conditions, integration with laboratory information management systems, data integrity controls specific to the user’s quality system, analyst training effectiveness. These aspects are highly dependent on the specific analytical methods, products, and laboratory environment.

For analytical systems involved in release testing, additional considerations include:

- Verification of method transfer from development to quality control laboratories

- Demonstration of consistent performance across multiple analysts

- Confirmation of data integrity throughout the complete testing process

- Integration with the laboratory’s sample management and result reporting systems

- Alignment with regulatory filing commitments for analytical methods

This qualification strategy ensures that standard instrument functionality is efficiently verified through supplier documentation while focusing end-user resources on the product-specific aspects critical to reliable analytical results.

Conclusion: Best Practices for Supplier Documentation in Biotech Qualification

To maximize the benefits of supplier documentation while ensuring regulatory compliance in biotech qualification:

- Develop clear supplier requirements early in the procurement process, with specific documentation expectations communicated before equipment design and manufacturing. These requirements should specifically address documentation format, content, and quality standards.

- Establish formal supplier assessment processes with clear criteria aligned with regulatory expectations and internal quality standards. These assessments should be performed by multidisciplinary teams including quality, engineering, and manufacturing representatives.

- Implement quality agreements with key equipment suppliers, explicitly defining responsibilities for documentation, testing, and qualification activities. These agreements should include specifics on documentation standards, testing protocols, and data integrity requirements.

- Create standardized processes for reviewing and accepting supplier documentation based on criticality and risk assessment. These processes should include formal gap analysis and identification of supplemental testing requirements.

- Apply risk-based approaches consistently when determining what can be leveraged, focusing qualification resources on aspects with highest potential impact on product quality. Risk assessments should be documented with clear rationales for acceptance decisions.

- Document rationale thoroughly for acceptance decisions, including scientific justification and regulatory considerations. Documentation should demonstrate a systematic evaluation process with appropriate quality oversight.

- Maintain appropriate quality oversight throughout the process, with quality unit involvement in key decisions regarding supplier documentation acceptance. Quality representatives should review and approve supplier assessment reports and qualification plans.

- Implement verification activities targeting gaps and high-risk areas identified during document review, focusing on process-specific and integration aspects. Verification testing should be designed to complement, not duplicate, supplier testing.

- Integrate supplier documentation within your qualification lifecycle approach, establishing clear linkages between supplier testing and overall qualification requirements. Traceability matrices should demonstrate how supplier documentation contributes to meeting qualification requirements.

The key is finding the right balance between leveraging supplier expertise and maintaining appropriate end-user verification of critical aspects that impact product quality and patient safety. Proper evaluation and integration of supplier documentation represents a significant opportunity to enhance qualification efficiency while maintaining the rigorous standards essential for biotech products. With clear criteria for acceptance, systematic risk assessment, and thorough documentation, organizations can confidently leverage supplier documentation as part of a comprehensive qualification strategy aligned with current regulatory expectations and quality best practices.