In modern organizational dynamics, complacency operates as a silent saboteur—eroding innovation, stifling growth, and undermining the very foundations of quality culture. Defined as a state of self-satisfaction paired with unawareness of deficiencies, complacency creates cyclical patterns that perpetuate mediocrity and resistance to change. When left unchecked, these cycles corrode organizational resilience, diminish stakeholder trust, and jeopardize long-term viability. Conversely, a robust quality culture—characterized by shared values prioritizing excellence and continuous improvement—serves as the antidote.

The Anatomy of Complacency Cycles

Complacency arises when employees or teams grow overly comfortable with existing processes, outcomes, or performance levels. This manifests as:

Reduced Vigilance: The Silent Erosion of Risk Awareness

Reduced vigilance represents a critical failure mode in quality management systems, where repetitive tasks or historical success breed dangerous overconfidence. In manufacturing environments, for instance, workers performing identical quality checks thousands of times often develop “checklist fatigue”—a phenomenon where muscle memory replaces active observation. This complacency manifests in subtle but impactful ways:

- Automation Blindness: Operators monitoring automated systems grow dependent on technology, failing to notice gradual sensor drift.

- Normalization of Deviations

- Metric Myopia: Organizations relying solely on lagging indicators like defect rates miss emerging risks.

The neuroscience behind this phenomenon reveals disturbing patterns: fMRI scans show reduced prefrontal cortex activation during routine quality checks compared to novel tasks, indicating genuine cognitive disengagement rather than intentional negligence.

Resistance to Innovation: The Institutionalization of Obsolescence

Complacency-driven resistance to innovation creates organizational calcification, where legacy processes become dogma despite market evolution. This dynamic operates through three interconnected mechanisms:

- Cognitive Lock-In: Teams develop “expertise traps” where deep familiarity with existing methods blinds them to superior alternatives.

- Risk Asymmetry Perception: Employees overestimate innovation risks while underestimating stagnation risks.

- Hierarchical Inertia: Leadership teams reward incremental improvements over transformational change.

Disengagement: The Metastasis of Organizational Apathy

Disengagement in complacent cultures operates as both symptom and accelerant, creating self-reinforcing cycles of mediocrity. Key dimensions include:

Cognitive Disinvestment: Employees mentally “clock out” during critical tasks. .

Professional Stagnation: Complacency suppresses upskilling initiatives.

Social Contagion Effects: Disengagement spreads virally through teams.

This triad of vigilance erosion, innovation resistance, and workforce disengagement forms a self-perpetuating complacency cycle that only conscious, systemic intervention can disrupt.

These behaviors form self-reinforcing loops. For example, employees who receive inadequate feedback may disengage, leading to errors that management ignores, further normalizing subpar performance.

The Four-Phase Complacency Cycle

- Stagnation Phase: Initial success or routine workflows breed overconfidence. Teams prioritize efficiency over improvement, dismissing early warning signs.

- Normalization of Risk: Minor deviations from standards (e.g., skipped safety checks) become habitual. NASA’s Columbia disaster post-mortem highlighted how normalized risk-taking eroded safety protocols.

- Crisis Trigger: Accumulated oversights culminate in operational failures—product recalls, safety incidents, or financial losses.

- Temporary Vigilance: Post-crisis, organizations implement corrective measures, but without systemic change, complacency resurges within months.

This cycle mirrors the “boom-bust” patterns observed in safety-critical industries, where post-incident reforms often lack staying power.

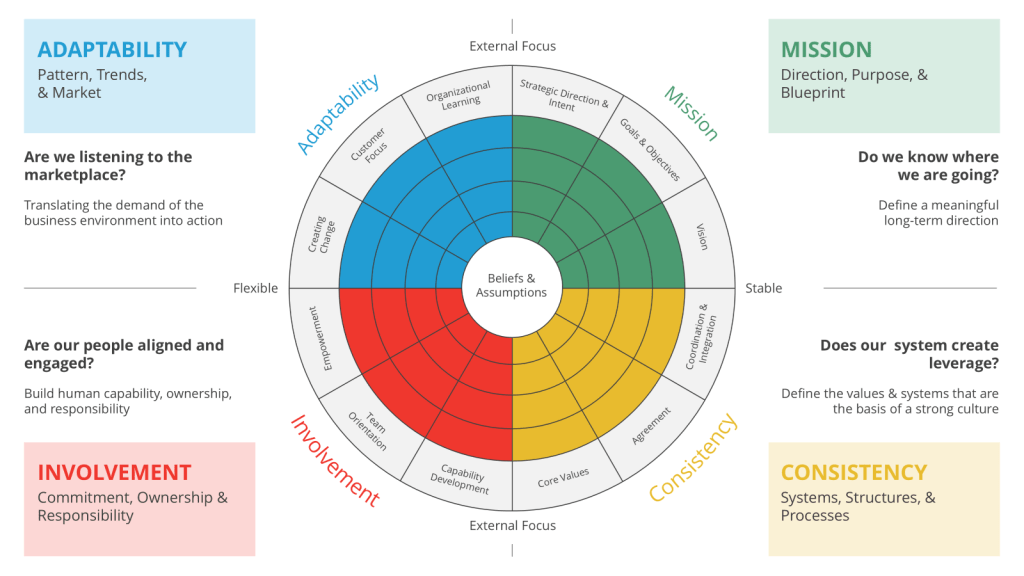

How Complacency Undermines Quality Culture

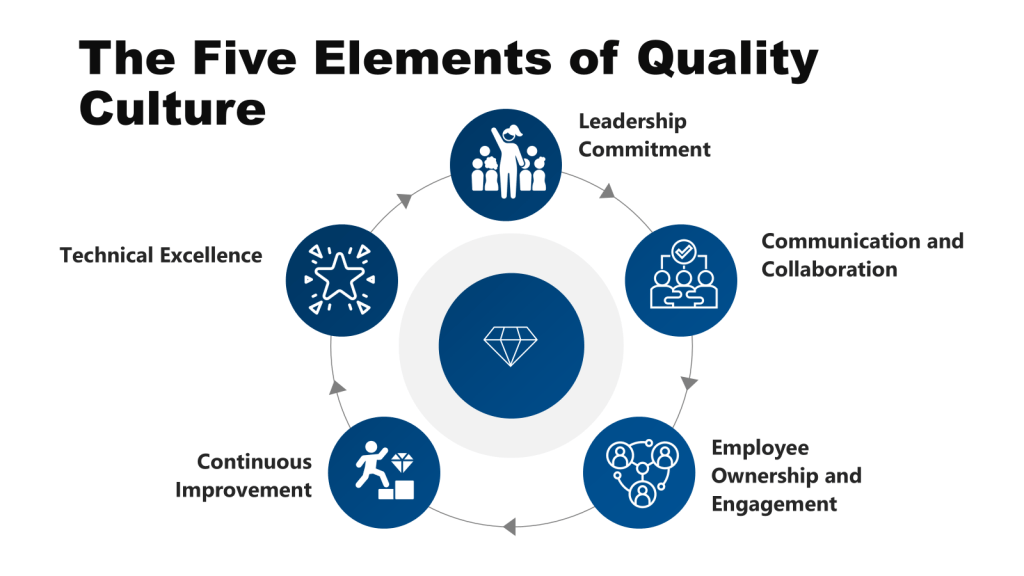

Leadership Commitment: The Compromise of Strategic Stewardship

Complacency transforms visionary leadership into passive oversight, directly undermining quality culture’s foundational pillar. When executives prioritize short-term operational efficiency over long-term excellence, they inadvertently normalize risk tolerance. This pattern reflects three critical failures:

- Resource Misallocation: Complacent leaders starve quality initiatives of funding.

- Ceremonial Governance

- Metric Manipulation

These behaviors create organizational whiplash—employees interpret leadership’s mixed signals as permission to deprioritize quality standards.

Communication & Collaboration: The Silencing of Collective Intelligence

Complacency breeds information silos that fracture quality systems. NASA’s Challenger disaster exemplifies how hierarchical filters and schedule pressures prevented engineers’ O-ring concerns from reaching decision-makers—a communication failure that cost lives and destroyed $3.2 billion in assets. Modern organizations replicate this dynamic through:

- Digital Fragmentation

- Meeting Rituals

- Knowledge Hoarding

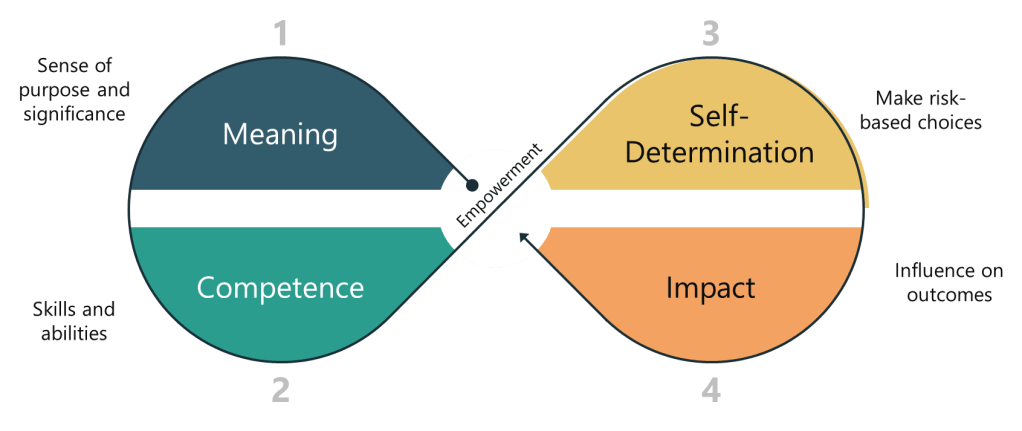

Employee Ownership & Engagement: The Death of Frontline Vigilance

Complacency converts empowered workforces into disengaged spectators.

- Problem-Solving Atrophy: Complacent environments resolve fewer issues proactively.

- Initiative Suppression

- Skill Erosion

Continuous Improvement: The Illusion of Progress

Complacency reduces a learning culture to kabuki theater—visible activity without substantive change. Other failure modes include:

- Incrementalism Trap

- Metric Myopia

- Benchmark Complacency

Technical Excellence: The Rot of Core Competencies

Complacency transforms cutting-edge capabilities into obsolete rituals. Specific erosion patterns include:

- Standards Creep

- Tribal Knowledge Loss

- Tooling Obsolescence

Mechanisms of Erosion

- Diminished Problem-Solving Rigor: Complacent teams favor quick fixes over root-cause analysis. In pharmaceuticals, retrospective risk assessments—used to justify releasing borderline batches—exemplify this decline.

- Erosion of Psychological Safety: Employees in complacent environments fear repercussions for raising concerns, leading to underreported issues.

- Supplier Quality Degradation: Over time, organizations accept lower-quality inputs to maintain margins, compromising end products.

- Customer Disengagement: As quality slips, customer feedback loops weaken, creating echo chambers of false confidence.

The automotive industry’s recurring recall crises—from ignition switches to emissions scandals—illustrate how complacency cycles gradually dismantle quality safeguards.

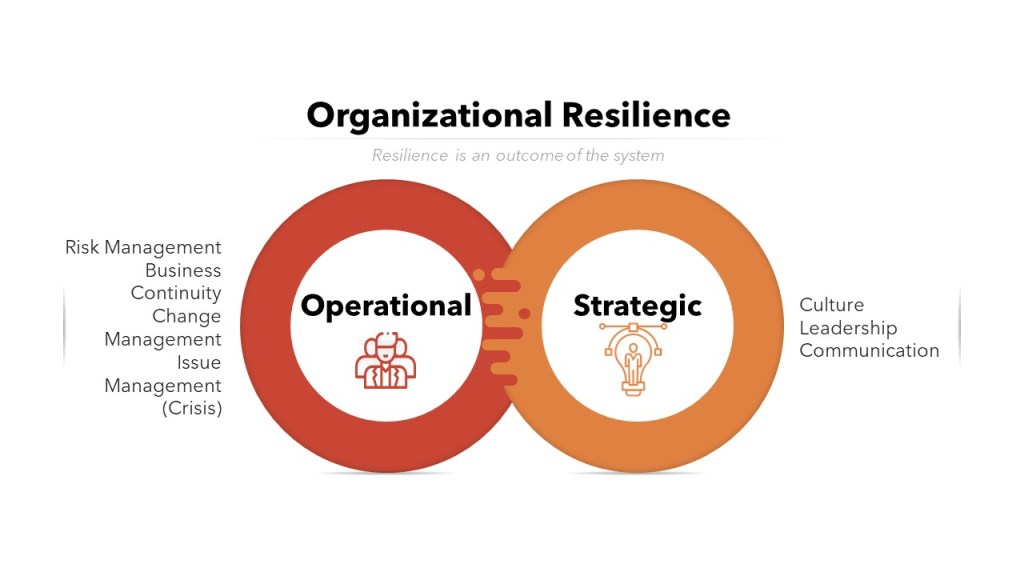

Leadership’s Pivotal Role in Breaking the Cycle

Leadership’s Pivotal Role in Breaking the Cycle

Leadership serves as the linchpin in dismantling complacency cycles, requiring a dual focus on strategic vision and operational discipline. Executives must first institutionalize quality as a non-negotiable organizational priority through tangible commitments. This begins with structurally aligning incentives—such as linking 30% of executive compensation to quality metrics like defect escape rates and preventative CAPA completion—to signal that excellence transcends rhetoric. For instance, a Fortune 500 medical device firm eliminated 72% of recurring compliance issues within 18 months by tying bonus structures to reduction targets for audit findings. Leaders must also champion resource allocation, exemplified by a semiconductor manufacturer dedicating 8% of annual R&D budgets to AI-driven predictive quality systems, which slashed wafer scrap rates by 57% through real-time anomaly detection.

Equally critical is leadership’s role in modeling vulnerability and transparency. When executives participate in frontline audits—as seen in a chemical company where CEOs joined monthly gemba walks—they not only uncover systemic risks but also normalize accountability. This cultural shift proved transformative for an automotive supplier, where C-suite attendance at shift-change safety briefings reduced OSHA recordables by 24% in one year. Leaders must also revamp metrics systems to emphasize leading indicators over lagging ones.

Operationalizing these principles demands tactical ingenuity. Dynamic goal-setting prevents stagnation. Cross-functional collaboration is accelerated through quality SWAT teams. Perhaps most impactful is leadership’s ability to democratize problem-solving through technology.

Ultimately, leaders dismantle complacency by creating systems where quality becomes everyone’s responsibility—not through mandates, but by fostering environments where excellence is psychologically safe, technologically enabled, and personally rewarding. This requires perpetual vigilance: celebrating quality wins while interrogating successes for hidden risks, ensuring today’s solutions don’t become tomorrow’s complacent norms.

Sustaining Quality Culture Through Anti-Complacency Practices

Sustaining Quality Culture Through Anti-Complacency Practices

Sustaining a quality culture demands deliberate practices that institutionalize vigilance against the creeping normalization of mediocrity. Central to this effort is the integration of continuous improvement methodologies into organizational workflows. Such systems thrive when paired with real-time feedback mechanisms—digital dashboards tracking suggestion implementation rates and their quantifiable impacts for example can create visible accountability loops.

Cultural reinforcement rituals further embed anti-complacency behaviors by celebrating excellence and fostering collective ownership. Monthly “Quality Hero” town halls at a pharmaceutical firm feature frontline staff sharing stories of critical interventions, such as a technician who averted 17,000 mislabeled vaccine doses by catching a vial mismatch during final packaging. This practice increased peer-driven quality audits by 63% within six months by humanizing the consequences of vigilance. Reverse mentoring programs add depth to this dynamic: junior engineers at an aerospace firm trained executives on predictive maintenance tools, bridging generational knowledge gaps while updating leadership perspectives on emerging risks.

Proactive risk mitigation tools like pre-mortem analyses disrupt complacency by forcing teams to confront hypothetical failures before they occur.

Immersive learning experiences make the stakes of complacency tangible. A medical device company’s “Harm Simulation Lab” recreates scenarios like patients coding from insulin pump software failures, exposing engineers to the human consequences of design oversights. Participants identified 112% more risks in subsequent reviews compared to peers trained through conventional lectures.

Together, these practices form an ecosystem where complacency struggles to take root. By aligning individual behaviors with systemic safeguards—from idea-driven improvement frameworks to emotionally resonant learning—organizations transform quality from a compliance obligation into a collective mission. The result is a self-reinforcing culture where vigilance becomes habitual, innovation feels inevitable, and excellence persists not through enforcement, but through institutionalized reflexes that outlast individual initiatives.

Conclusion: The Never-Ending Journey

Complacency cycles and quality culture exist in perpetual tension—the former pulling organizations toward entropy, the latter toward excellence. Breaking this cycle demands more than temporary initiatives; it requires embedding quality into organizational DNA through:

- Relentless leadership commitment to modeling and resourcing quality priorities.

- Systems thinking that connects individual actions to enterprise-wide outcomes.

- Psychological safety enabling transparent risk reporting and experimentation.

Sustained quality cultures are possible, but only through daily vigilance against complacency’s seductive pull. In an era of accelerating change, the organizations that thrive will be those recognizing that quality isn’t a destination—it’s a mindset forged through perpetual motion.