Companies both large and small grapple with how and when to create standard work at the global level, while still having the scalability to capture different GXP activity families and product modality.

I’ve discussed before on document hierarchy and on the leveling of process and procedure. It is really important to level your processes, and this architecture should be deliberate and shepherded.

This really gets to the heart of work-as-imagined and prescribed, and the concept of standard work.

Benefits of Standard Work

- Ensures all work is done according to the current best practice

- Consistency is the essential ingredient of quality

- Allows organizations to scale rapidly

- Puts the focus on the process and not an individual or team

- Makes improvements easier and faster

Global versus Local Process and Procedure in the Document Hierarchy

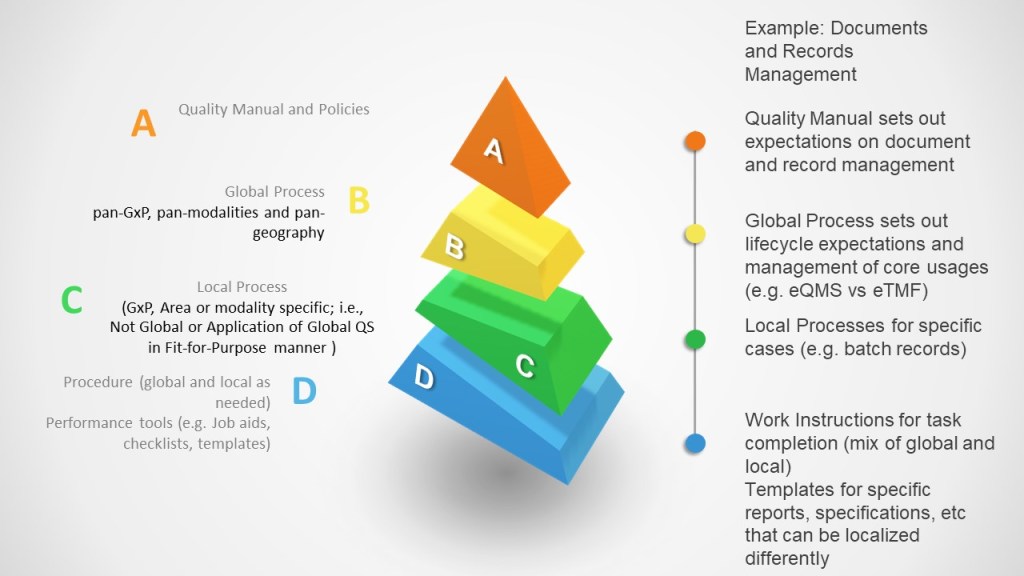

Most Quality Hierarchies look fairly similar.

Excluding the Program level (which becomes even more important) we can expand the model in the process band to account for global versus local.

Quality Manual and Policy remains global with local input and determine the overall structure of the quality management system.

Global Process is created when a process is majority task and role driven at a global level. It is pan-GXP, pan-modality, pan-geography. It is the standard way of work to drive consistency across and through the organization.

Local Process is created when a process is specific to a specific GXP, product modality, geography.

Procedure, which describes the tasks, can be created off of local or global process. When the global process has localizations (a CAPA is a CAPA but how I build action items may differ across sites), I can build local versions off the global process.

For an example, Document and Record Management.

This approach takes real vision among leaders to drive for consistency and simplicity. This activity is a core component in good system design, no matter the size of the organization.

| Principle | Description | Application for Global and Local Process |

| Balance | The system creates value for the multiple stakeholders. While the ideal is to develop a design that maximizes the value for all the key stakeholders, the designer often has to compromise and balance the needs of the various stakeholders. | The value of standard work really shines here. |

| Congruence | The degree to which the system components are aligned and consistent with each other and the other organizational systems, culture, plans, processes, information, resource decisions, and actions. | We gain congruence through ensuring key processes are at the global level. |

| Convenience | The system is designed to be as convenient as possible for the participants to implement (a.k.a. user friendly). System includes specific processes, procedures, and controls only when necessary. | The discussion around global versus local will often depend on how you define convenience |

| Coordination | System components are interconnected and harmonized with the other (internal and external) components, systems, plans, processes, information, and resource decisions toward common action or effort. This is beyond congruence and is achieved when the individual components of a system operate as a fully interconnected unit. | How we ensure coordination across and through an organization. |

| Elegance | Complexity vs. benefit — the system includes only enough complexity as is necessary to meet the stakeholder’s needs. In other words, keep the design as simple as possible and no more while delivering the desired benefits. It often requires looking at the system in new ways. | Keep this in mind as global for the sake of global is not always the right decision. |

| Human | Participants in the system are able to find joy, purpose and meaning in their work. | Never forget |

| Learning | Knowledge management, with opportunities for reflection and learning (learning loops), is designed into the system. Reflection and learning are built into the system at key points to encourage single- and double-loop learning from experience to improve future implementation and to systematically evaluate the design of the system itself. | Building the right knowledge management into the organization is critical to leverage this model |

| Sustainability | The system effectively meets the near- and long-term needs of the current stakeholders without compromising the ability of future generations of stakeholders to meet their own needs. | Ensure the appropriate tools exist to sustain, including regulatory intelligence. Long-term scalability. |

Utilizing the eQMS to drive

The ideal state when implementing (or improving) an eQMS is to establish global processes and allow system functionality to localize as appropriate.

So for example, every CAPA is the same (identify problem and root cause, create plan, implement plan, prove implementation is effective. This is a global process. However, one wants specific task detail at a lower level, for example GMP sites may care about certain fields more the GCP, medical device has specific needs, etc. These local task level needs can be mainted within one workflow.

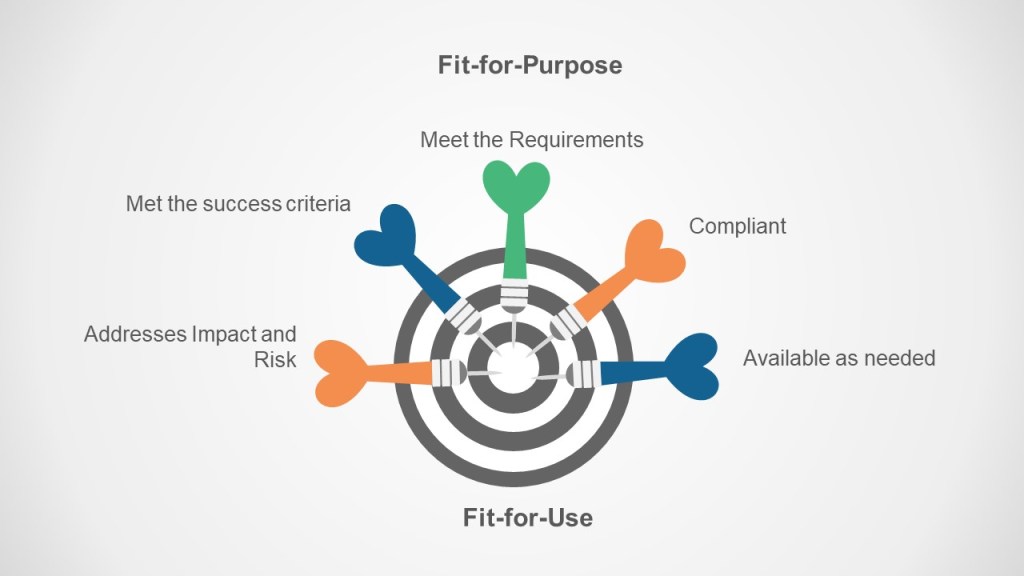

The Key is Fit-For-Purpose Fit-for-Use

A fit for purpose process meets the requirements of the organization.

A fit for use process is usable throughout the lifecycle.

Global and localizing processes is a key part of making both happen.