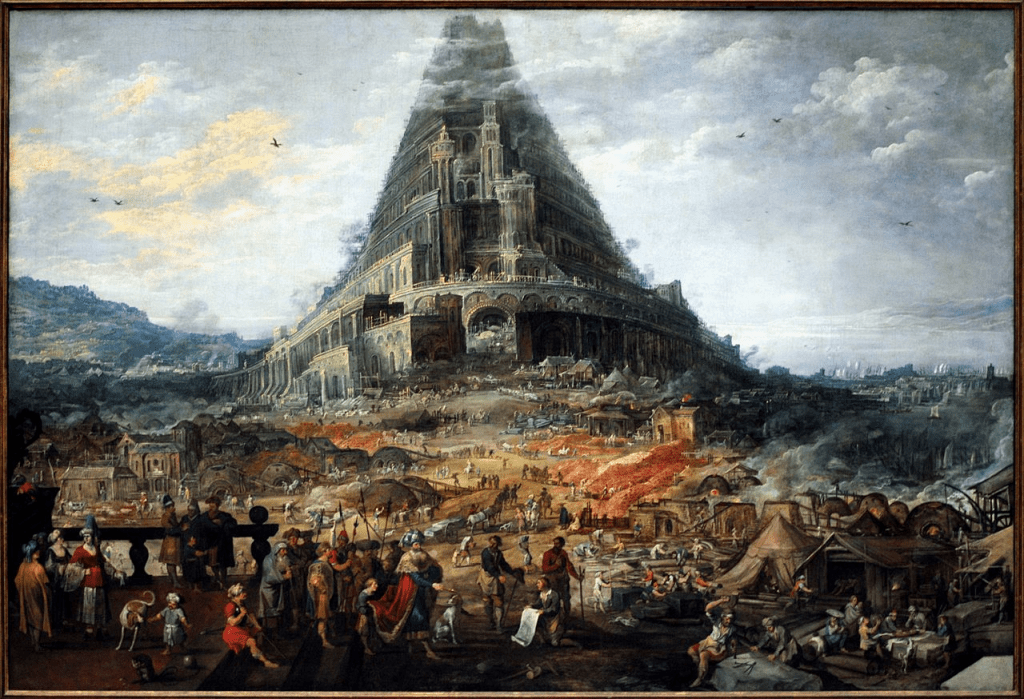

In complex industries such as aviation and biotechnology, effective communication is crucial for ensuring safety, quality, and efficiency. However, the presence of communication loops and silos can significantly hinder these efforts. The concept of the “Tower of Babel” problem, as explored in the aviation sector by Follet, Lasa, and Mieusset in HS36, highlights how different professional groups develop their own languages and operate within isolated loops, leading to misunderstandings and disconnections. This article has really got me thinking about similar issues in my own industry.

The Tower of Babel Problem: A Thought-Provoking Perspective

The HS36 article provides a thought-provoking perspective on the “Tower of Babel” problem, where each aviation professional feels in control of their work but operates within their own loop. This phenomenon is reminiscent of the biblical story where a common language becomes fragmented, causing confusion and separation among people. In modern industries, this translates into different groups using their own jargon and working in isolation, making it difficult for them to understand each other’s perspectives and challenges.

For instance, in aviation, air traffic controllers (ATCOs), pilots, and managers each have their own “loop,” believing they are in control of their work. However, when these loops are disconnected, it can lead to miscommunication, especially when each group uses different terminology and operates under different assumptions about how work should be done (work-as-prescribed vs. work-as-done). This issue is equally pertinent in the biotech industry, where scientists, quality assurance teams, and regulatory affairs specialists often work in silos, which can impede the development and approval of new products.

Impact on Decision Making

Decision making in biotech is heavily influenced by Good Practice (GxP) guidelines, which emphasize quality, safety, and compliance – and I often find that the aviation industry, as a fellow highly regulated industry, is a great place to draw perspective.

When communication loops are disconnected, decisions may not fully consider all relevant perspectives. For example, in GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) environments, quality control teams might focus on compliance with regulatory standards, while research and development teams prioritize innovation and efficiency. If these groups do not effectively communicate, decisions might overlook critical aspects, such as the practicality of implementing new manufacturing processes or the impact on product quality.

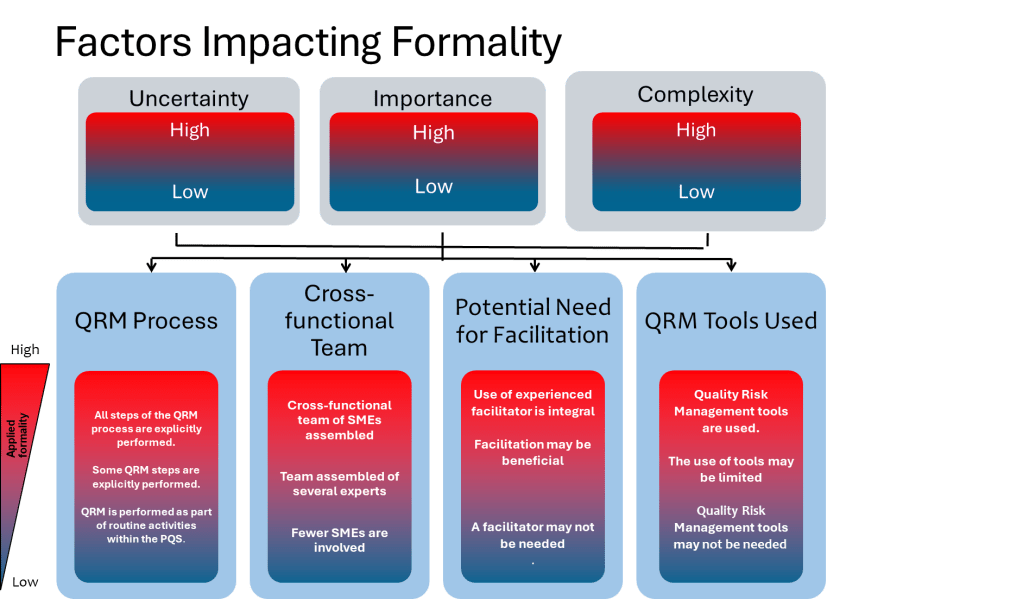

Furthermore, ICH Q9(R1) guideline emphasizes the importance of reducing subjectivity in Quality Risk Management (QRM) processes. Subjectivity can arise from personal opinions, biases, or inconsistent interpretations of risks by stakeholders, impacting every stage of QRM. To combat this, organizations must adopt structured approaches that prioritize scientific knowledge and data-driven decision-making. Effective knowledge management is crucial in this context, as it involves systematically capturing, organizing, and applying internal and external knowledge to inform QRM activities.

Academic Research on Communication Loops

Research in organizational behavior and communication highlights the importance of bridging these silos. Studies have shown that informal interactions and social events can significantly improve relationships and understanding among different professional groups (Katz & Fodor, 1963). In the biotech industry, fostering a culture of open communication can help ensure that GxP decisions are well-rounded and effective.

Moreover, the concept of “work-as-done” versus “work-as-prescribed” is relevant in biotech as well. Operators may adapt procedures to fit practical realities, which can lead to discrepancies between intended and actual practices. This gap can be bridged by encouraging feedback and continuous improvement processes, ensuring that decisions reflect both regulatory compliance and operational feasibility.

Case Studies and Examples

- Aviation Example: The HS36 article provides a compelling example of how disconnected loops can hinder effective decision making in aviation. For instance, when a standardized phraseology was introduced, frontline operators felt that this change did not account for their operational needs, leading to resistance and potential safety issues. This illustrates how disconnected loops can hinder effective decision making.

- Product Development: In the development of a new biopharmaceutical, different teams might have varying priorities. If the quality assurance team focuses solely on regulatory compliance without fully understanding the manufacturing challenges faced by production teams, this could lead to delays or quality issues. By fostering cross-functional communication, these teams can align their efforts to ensure both compliance and operational efficiency.

- ICH Q9(R1) Example: The revised ICH Q9(R1) guideline emphasizes the need to manage and minimize subjectivity in QRM. For instance, in assessing the risk of a new manufacturing process, a structured approach using historical data and scientific evidence can help reduce subjective biases. This ensures that decisions are based on comprehensive data rather than personal opinions.

- Technology Deployment: . A recent FDA Warning Letter to Sanofi highlighted the importance of timely technological upgrades to equipment and facility infrastructure. This emphasizes that staying current with technological advancements is essential for maintaining regulatory compliance and ensuring product quality. However the individual loops of decision making amongst the development teams, operations and quality can lead to major mis-steps.

Strategies for Improvement

To overcome the challenges posed by communication loops and silos, organizations can implement several strategies:

- Promote Cross-Functional Training: Encourage professionals to explore other roles and challenges within their organization. This can help build empathy and understanding across different departments.

- Foster Informal Interactions: Organize social events and informal meetings where professionals from different backgrounds can share experiences and perspectives. This can help bridge gaps between silos and improve overall communication.

- Define Core Knowledge: Establish a minimum level of core knowledge that all stakeholders should possess. This can help ensure that everyone has a basic understanding of each other’s roles and challenges.

- Implement Feedback Loops: Encourage continuous feedback and improvement processes. This allows organizations to adapt procedures to better reflect both regulatory requirements and operational realities.

- Leverage Knowledge Management: Implement robust knowledge management systems to reduce subjectivity in decision-making processes. This involves capturing, organizing, and applying internal and external knowledge to inform QRM activities.

Combating Subjectivity in Decision Making

In addition to bridging communication loops, reducing subjectivity in decision making is crucial for ensuring quality and safety. The revised ICH Q9(R1) guideline provides several strategies for this:

- Structured Approaches: Use structured risk assessment tools and methodologies to minimize personal biases and ensure that decisions are based on scientific evidence.

- Data-Driven Decision Making: Prioritize data-driven decision making by leveraging historical data and real-time information to assess risks and opportunities.

- Cognitive Bias Awareness: Train stakeholders to recognize and mitigate cognitive biases that can influence risk assessments and decision-making processes.

Conclusion

In complex industries effective communication is essential for ensuring safety, quality, and efficiency. The presence of communication loops and silos can lead to misunderstandings and poor decision making. By promoting cross-functional understanding, fostering informal interactions, and implementing feedback mechanisms, organizations can bridge these gaps and improve overall performance. Additionally, reducing subjectivity in decision making through structured approaches and data-driven decision making is critical for ensuring compliance with GxP guidelines and maintaining product quality. As industries continue to evolve, addressing these communication challenges will be crucial for achieving success in an increasingly interconnected world.

References:

- Follet, S., Lasa, S., & Mieusset, L. (n.d.). The Tower of Babel Problem in Aviation. In HindSight Magazine, HS36. Retrieved from https://skybrary.aero/sites/default/files/bookshelf/hs36/HS36-Full-Magazine-Hi-Res-Screen-v3.pdf

- Katz, D., & Fodor, J. (1963). The Structure of a Semantic Theory. Language, 39(2), 170–210.

- Dekker, S. W. A. (2014). The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error. Ashgate Publishing.

- Shorrock, S. (2023). Editorial. Who are we to judge? From work-as-done to work-as-judged. HindSight, 35, Just Culture…Revisited. Brussels: EUROCONTROL.