The pharmaceutical industry has long operated under what Michael Hudson aptly describes in his recent Forbes article as “symphonic control, “carefully orchestrated strategies executed with rigid precision, where quality units can function like conductors trying to control every note. But as Hudson observes, when our meticulously crafted risk assessments collide with chaotic reality, what emerges is often discordant. The time has come for quality risk management to embrace what I am going to call “rhythmic excellence,” a jazz-inspired approach that maintains rigorous standards while enabling adaptive performance in our increasingly BANI (Brittle, Anxious, Non-linear, and Incomprehensible) regulatory and manufacturing environment.

And since I love a good metaphor, I bring you:

Rhythmic Quality Risk Management

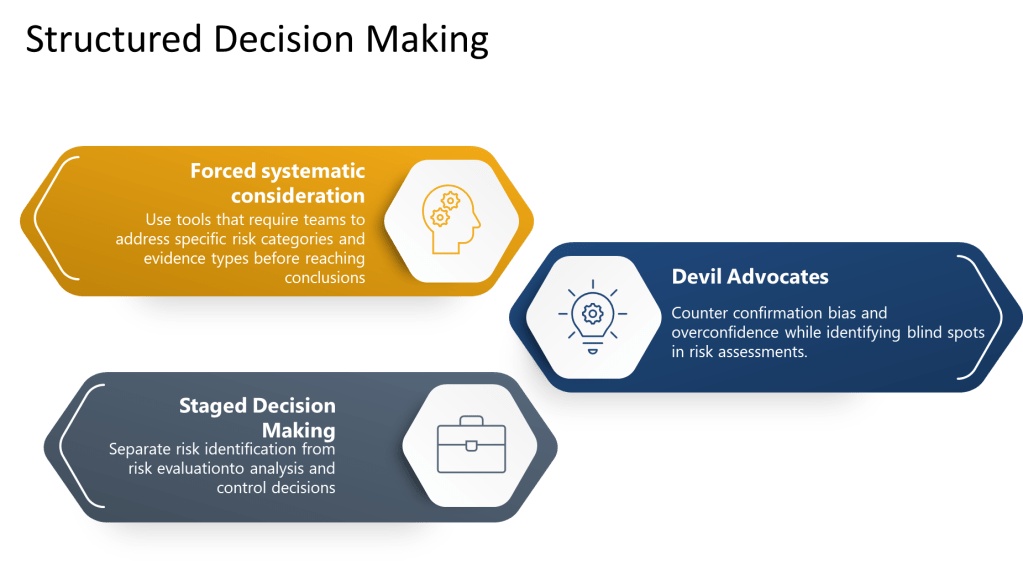

Recent research by Amy Edmondson and colleagues at Harvard Business School provides compelling evidence for rhythmic approaches to complex work. After studying more than 160 innovation teams, they found that performance suffered when teams mixed reflective activities (like risk assessments and control strategy development) with exploratory activities (like hazard identification and opportunity analysis) in the same time period. The highest-performing teams established rhythms that alternated between exploration and reflection, creating distinct beats for different quality activities.

This finding resonates deeply with the challenges we face in pharmaceutical quality risk management. Too often, our risk assessment meetings become frantic affairs where hazard identification, risk analysis, control strategy development, and regulatory communication all happen simultaneously. Teams push through these sessions exhausted and unsatisfied, delivering risk assessments they aren’t proud of—what Hudson describes as “cognitive whiplash”.

From Symphonic Control to Jazz-Based Quality Leadership

The traditional approach to pharmaceutical quality risk management mirrors what Hudson calls symphonic leadership—attempting to impose top-down structure as if more constraint and direction are what teams need to work with confidence. We create detailed risk assessment procedures, prescriptive FMEA templates, and rigid review schedules, then wonder why our teams struggle to adapt when new hazards emerge or when manufacturing conditions change unexpectedly.

Karl Weick’s work on organizational sensemaking reveals why this approach undermines our quality objectives: complex manufacturing environments require “mindful organizing” and the ability to notice subtle changes and respond fluidly. Setting a quality rhythm and letting go of excessive control provides support without constraint, giving teams the freedom to explore emerging risks, experiment with novel control strategies, and make sense of the quality challenges they face.

This represents a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize quality risk management leadership. Instead of being the conductor trying to orchestrate every risk assessment note, quality leaders should function as the rhythm section—establishing predictable beats that keep everyone synchronized while allowing individual expertise to flourish.

The Quality Rhythm Framework: Four Essential Beats

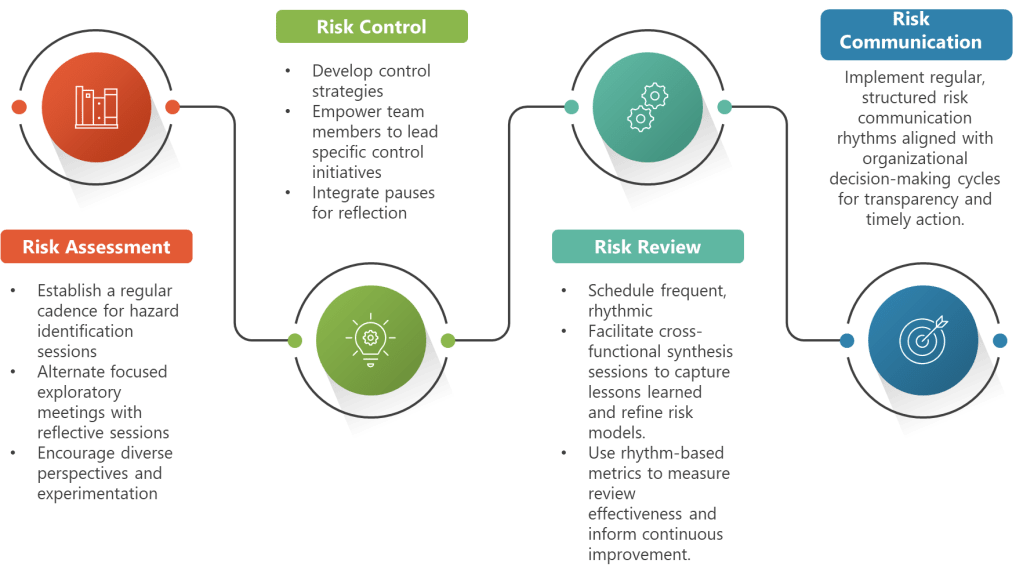

Drawing from Hudson’s research-backed insights and integrating them with ICH Q9(R1) requirements, I envision a Quality Rhythm Framework built on four essential beats:

Beat 1: Find Your Risk Cadence

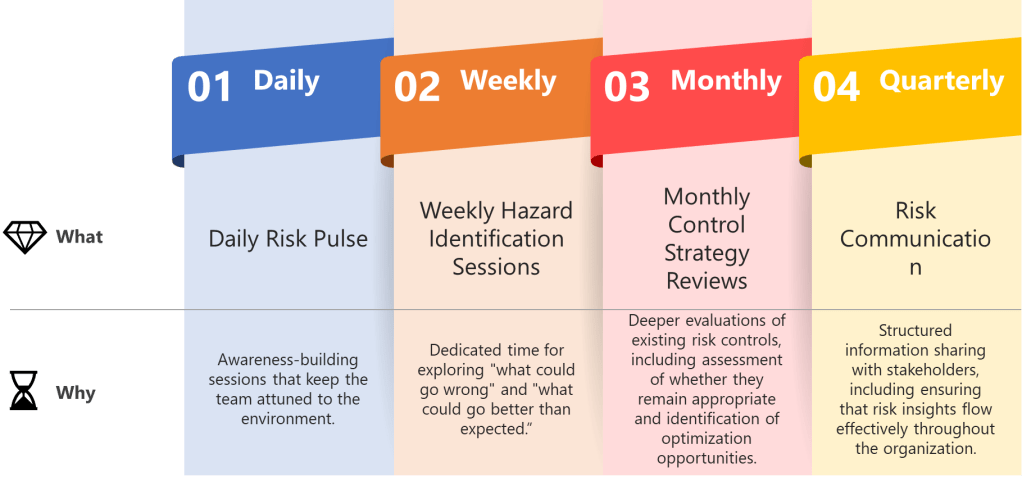

Establish predictable rhythms that create temporal anchors for your quality team while maintaining ICH Q9 compliance. Weekly hazard identification sessions, daily deviation assessments, monthly control strategy reviews, and quarterly risk communication cycles aren’t just meetings—they’re the beats that keep everyone synchronized while allowing individual risk management expression.

The ICH Q9(R1) revision’s emphasis on proportional formality aligns perfectly with this rhythmic approach. High-risk processes require more frequent beats, while lower-risk areas can operate with extended rhythms. The key is consistency within each risk category, creating what Weick calls “structured flexibility”—the ability to respond creatively within clear boundaries.

Consider implementing these quality-specific rhythmic structures:

- Daily Risk Pulse: Brief stand-ups focused on emerging quality signals—not comprehensive risk assessments, but awareness-building sessions that keep the team attuned to the manufacturing environment.

- Weekly Hazard Identification Sessions: Dedicated time for exploring “what could go wrong” and, following ISO 31000 principles, “what could go better than expected.” These sessions should alternate between different product lines or process areas to maintain focus.

- Monthly Control Strategy Reviews: Deeper evaluations of existing risk controls, including assessment of whether they remain appropriate and identification of optimization opportunities.

- Quarterly Risk Communication Cycles: Structured information sharing with stakeholders, including regulatory bodies when appropriate, ensuring that risk insights flow effectively throughout the organization.

Beat 2: Pause for Quality Breaths

Hudson emphasizes that jazz musicians know silence is as important as sound, and quality risk management desperately needs structured pauses. Build quality breaths into your organizational rhythm—moments for reflection, integration, and recovery from the intense focus required for effective risk assessment.

Research by performance expert Jim Loehr demonstrates that sustainable excellence requires oscillation, not relentless execution. In quality contexts, this means creating space between intensive risk assessment activities and implementation of control strategies. These pauses allow teams to process complex risk information, integrate diverse perspectives, and avoid the decision fatigue that leads to poor risk judgments.

Practical quality breaths include:

- Post-Assessment Integration Time: Following comprehensive risk assessments, build in periods where team members can reflect on findings, consult additional resources, and refine their thinking before finalizing control strategies.

- Cross-Functional Synthesis Sessions: Regular meetings where different functions (Quality, Operations, Regulatory, Technical) come together not to make decisions, but to share perspectives and build collective understanding of quality risks.

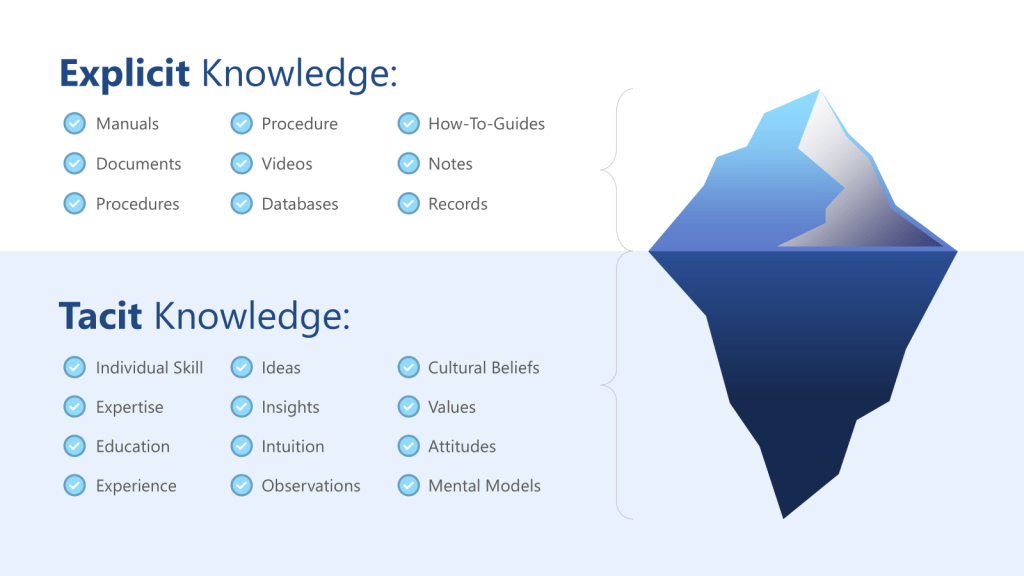

- Knowledge Capture Moments: Structured time for documenting lessons learned, updating risk models based on new experience, and creating institutional memory that enhances future risk assessments.

Beat 3: Encourage Quality Experimentation

Within your rhythmic structure, create psychological safety and confidence that team members can explore novel risk identification approaches without fear of hitting “wrong notes.” When learning and reflection are part of a predictable beat, trust grows and experimentation becomes part of the quality flow.

The ICH Q9(R1) revision’s focus on managing subjectivity in risk assessments creates opportunities for experimental approaches. Instead of viewing subjectivity as a problem to eliminate, we can experiment with structured methods for harnessing diverse perspectives while maintaining analytical rigor.

Hudson’s research shows that predictable rhythm facilitates innovation—when people are comfortable with the rhythm, they’re free to experiment with the melody. In quality risk management, this means establishing consistent frameworks that enable creative hazard identification and innovative control strategy development.

Experimental approaches might include:

- Success Mode and Benefits Analysis (SMBA): As I’ve discussed previously, complement traditional FMEA with systematic identification of positive potential outcomes. Experiment with different SMBA formats and approaches to find what works best for specific process areas.

- Cross-Industry Risk Insights: Dedicate portions of risk assessment sessions to exploring how other industries handle similar quality challenges. These experiments in perspective-taking can reveal blind spots in traditional pharmaceutical approaches.

- Scenario-Based Risk Planning: Experiment with “what if” exercises that go beyond traditional failure modes to explore complex, interdependent risk situations that might emerge in dynamic manufacturing environments.

Beat 4: Enable Quality Solos

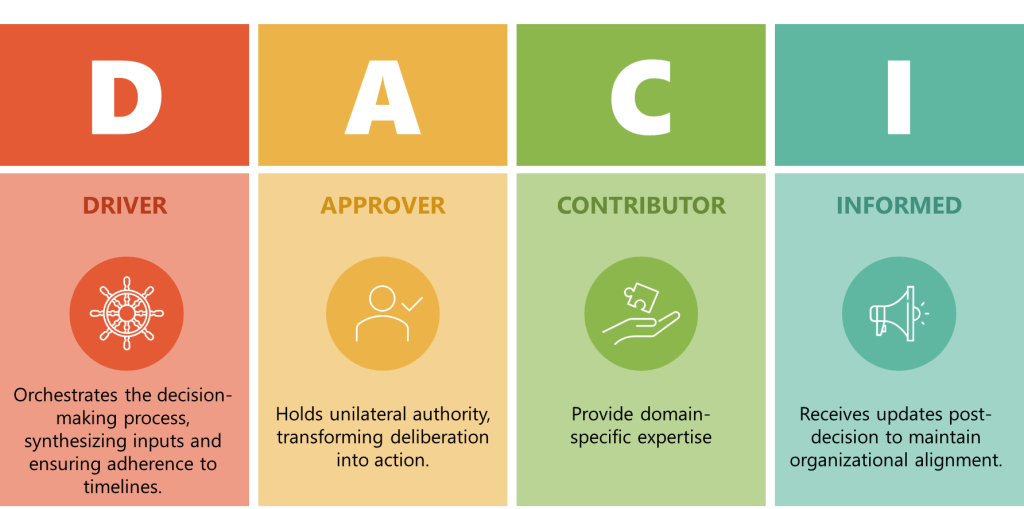

Just as jazz musicians trade solos while the ensemble provides support, look for opportunities for individual quality team members to drive specific risk management initiatives. This distributed leadership approach builds capability while maintaining collective coherence around quality objectives.

Hudson’s framework emphasizes that adaptive leaders don’t try to be conductors but create conditions for others to lead. In quality risk management, this means identifying team members with specific expertise or interest areas and empowering them to lead risk assessments in those domains.

Quality leadership solos might include:

- Process Expert Risk Leadership: Assign experienced operators or engineers to lead risk assessments for processes they know intimately, with quality professionals providing methodological support.

- Cross-Functional Risk Coordination: Empower individuals to coordinate risk management across organizational boundaries, taking ownership for ensuring all relevant perspectives are incorporated.

- Innovation Risk Championship: Designate team members to lead risk assessments for new technologies or novel approaches, building expertise in emerging quality challenges.

The Rhythmic Advantage: Three Quality Transformation Benefits

Mastering these rhythmic approaches to quality risk management provide three advantages that mirror Hudson’s leadership research:

Fluid Quality Structure

A jazz ensemble can improvise because musicians share a rhythm. Similarly, quality rhythms keep teams functioning together while offering freedom to adapt to emerging risks, changing regulatory requirements, or novel manufacturing challenges. Management researchers call this “structured flexibility”—exactly what ICH Q9(R1) envisions when it emphasizes proportional formality.

When quality teams operate with shared rhythms, they can respond more effectively to unexpected events. A contamination incident doesn’t require completely reinventing risk assessment approaches—teams can accelerate their established rhythms, bringing familiar frameworks to bear on novel challenges while maintaining analytical rigor.

Sustainable Quality Energy

Quality risk management is inherently demanding work that requires sustained attention to complex, interconnected risks. Traditional approaches often lead to burnout as teams struggle with relentless pressure to identify every possible hazard and implement perfect controls. Rhythmic approaches prevent this exhaustion by regulating pace and integrating recovery.

More importantly, rhythmic quality management aligns teams around purpose and vision rather than merely compliance deadlines. This enables what performance researchers call “sustainable high performance”—quality excellence that endures rather than depletes organizational energy.

When quality professionals find rhythm in their risk management work, they develop what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi identified as “flow state,” moments when attention is fully focused and performance feels effortless. These states are crucial for the deep thinking required for effective hazard identification and the creative problem-solving needed for innovative control strategies.

Enhanced Quality Trust and Innovation

The paradox Hudson identifies, that some constraint enables creativity, applies directly to quality risk management. Predictable rhythms don’t stifle innovation; they provide the stable foundation from which teams can explore novel approaches to quality challenges.

When quality teams know they have regular, structured opportunities for risk exploration, they’re more willing to raise difficult questions, challenge assumptions, and propose unconventional solutions. The rhythm creates psychological safety for intellectual risk-taking within the controlled environment of systematic risk assessment.

This enhanced innovation capability is particularly crucial as pharmaceutical manufacturing becomes increasingly complex, with continuous manufacturing, advanced process controls, and novel drug modalities creating quality challenges that traditional risk management approaches weren’t designed to address.

Integrating Rhythmic Principles with ICH Q9(R1) Compliance

The beauty of rhythmic quality risk management lies in its fundamental compatibility with ICH Q9(R1) requirements. The revision’s emphasis on scientific knowledge, proportional formality, and risk-based decision-making aligns perfectly with rhythmic approaches that create structured flexibility for quality teams.

Rhythmic Risk Assessment Enhancement

ICH Q9 requires systematic hazard identification, risk analysis, and risk evaluation. Rhythmic approaches enhance these activities by establishing regular, focused sessions for each component rather than trying to accomplish everything in marathon meetings.

During dedicated hazard identification beats, teams can employ diverse techniques—traditional brainstorming, structured what-if analysis, cross-industry benchmarking, and the Success Mode and Benefits Analysis I’ve advocated. The rhythm ensures these activities receive appropriate attention while preventing the cognitive overload that reduces identification effectiveness.

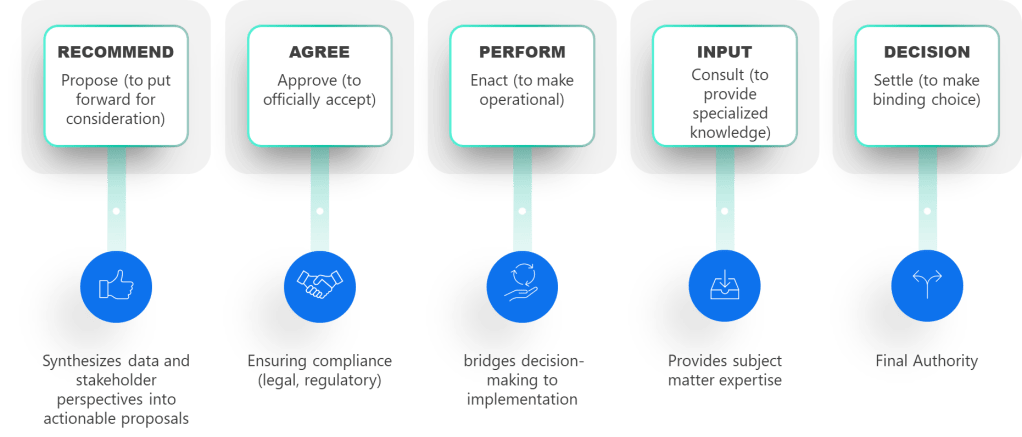

Risk analysis benefits from rhythmic separation between data gathering and interpretation activities. Teams can establish rhythms for collecting process data, manufacturing experience, and regulatory intelligence, followed by separate beats for analyzing this information and developing risk models.

Rhythmic Risk Control Development

The ICH Q9(R1) emphasis on risk-based decision-making aligns perfectly with rhythmic approaches to control strategy development. Instead of rushing from risk assessment to control implementation, rhythmic approaches create space for thoughtful strategy development that considers multiple options and their implications.

Rhythmic control development might include beats for:

- Control Strategy Ideation: Creative sessions focused on generating potential control approaches without immediate evaluation of feasibility or cost.

- Implementation Planning: Separate sessions for detailed planning of selected control strategies, including resource requirements, timeline development, and change management considerations.

- Effectiveness Assessment: Regular rhythms for evaluating implemented controls, gathering performance data, and identifying optimization opportunities.

Rhythmic Risk Communication

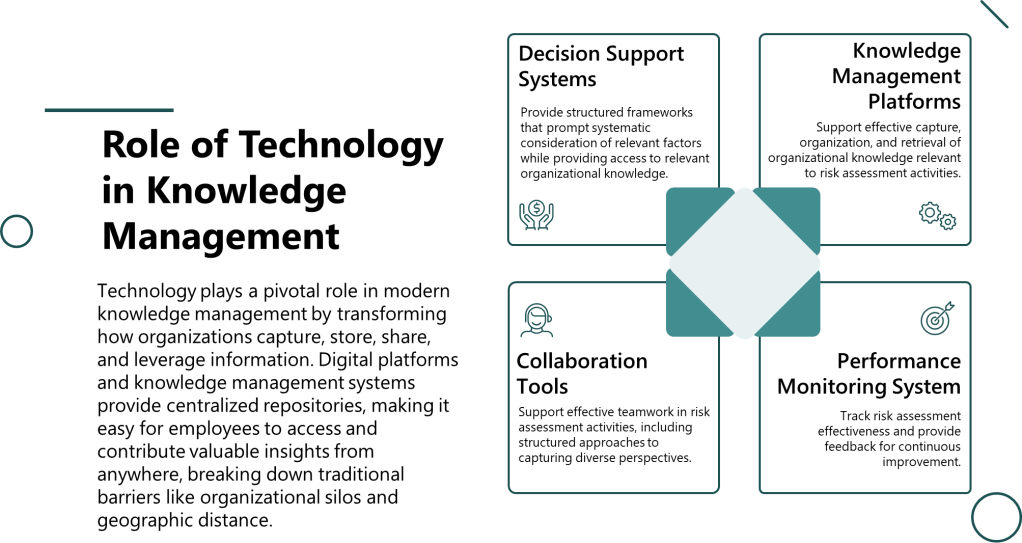

ICH Q9’s communication requirements benefit significantly from rhythmic approaches. Instead of ad hoc communication when problems arise, establish regular rhythms for sharing risk insights, control strategy updates, and lessons learned.

Quality communication rhythms should align with organizational decision-making cycles, ensuring that risk insights reach stakeholders when they’re most useful for decision-making. This might include monthly updates to senior leadership, quarterly reports to regulatory affairs, and annual comprehensive risk reviews for long-term strategic planning.

Practical Implementation: Building Your Quality Rhythm

Implementing rhythmic quality risk management requires systematic integration rather than wholesale replacement of existing approaches. Start by evaluating your current risk management processes to identify natural rhythm points and opportunities for enhancement.

Phase 1: Rhythm Assessment and Planning

Map your existing quality risk management activities against rhythmic principles. Identify where teams experience the cognitive whiplash Hudson describes—trying to accomplish too many different types of thinking in single sessions. Look for opportunities to separate exploration from analysis, strategy development from implementation planning, and individual reflection from group decision-making.

Establish criteria for quality rhythm frequency based on risk significance, process complexity, and organizational capacity. High-risk processes might require daily pulse checks and weekly deep dives, while lower-risk areas might operate effectively with monthly assessment rhythms.

Train quality teams on rhythmic principles and their application to risk management. Help them understand how rhythm enhances rather than constrains their analytical capabilities, providing structure that enables deeper thinking and more creative problem-solving.

Phase 2: Pilot Program Development

Select pilot areas where rhythmic approaches are most likely to demonstrate clear benefits. New product development projects, technology implementation initiatives, or process improvement activities often provide ideal testing grounds because their inherent uncertainty creates natural opportunities for both risk management and opportunity identification.

Design pilot programs to test specific rhythmic principles:

- Rhythm Separation: Compare traditional comprehensive risk assessment meetings with rhythmic approaches that separate hazard identification, risk analysis, and control strategy development into distinct sessions.

- Quality Breathing: Experiment with structured pauses between intensive risk assessment activities and measure their impact on decision quality and team satisfaction.

- Distributed Leadership: Identify opportunities for team members to lead specific aspects of risk management and evaluate the impact on engagement and expertise development.

Phase 3: Organizational Integration

Based on pilot results, develop systematic approaches for scaling rhythmic quality risk management across the organization. This requires integration with existing quality systems, regulatory processes, and organizational governance structures.

Consider how rhythmic approaches will interact with regulatory inspection activities, change control processes, and continuous improvement initiatives. Ensure that rhythmic flexibility doesn’t compromise documentation requirements or audit trail integrity.

Establish metrics for evaluating rhythmic quality risk management effectiveness, including both traditional risk management indicators (incident rates, control effectiveness, regulatory compliance) and rhythm-specific measures (team engagement, innovation frequency, decision speed).

Phase 4: Continuous Enhancement and Cultural Integration

Like all aspects of quality risk management, rhythmic approaches require continuous improvement based on experience and changing needs. Regular assessment of rhythm effectiveness helps refine approaches over time and ensures sustained benefits.

The ultimate goal is cultural integration—making rhythmic thinking a natural part of how quality professionals approach risk management challenges. This requires consistent leadership modeling, recognition of rhythmic successes, and integration of rhythmic principles into performance expectations and career development.

Measuring Rhythmic Quality Success

Traditional quality metrics focus primarily on negative outcome prevention: deviation rates, batch failures, regulatory findings, and compliance scores. While these remain important, rhythmic quality risk management requires expanded measurement approaches that capture both defensive effectiveness and adaptive capability.

Enhanced metrics should include:

- Rhythm Consistency Indicators: Frequency of established quality rhythms, participation rates in rhythmic activities, and adherence to planned cadences.

- Innovation and Adaptation Measures: Number of novel risk identification approaches tested, implementation rate of creative control strategies, and frequency of process improvements emerging from risk management activities.

- Team Engagement and Development: Participation in quality leadership opportunities, cross-functional collaboration frequency, and professional development within risk management capabilities.

- Decision Quality Indicators: Time from risk identification to control implementation, stakeholder satisfaction with risk communication, and long-term effectiveness of implemented controls.

Regulatory Considerations: Communicating Rhythmic Value

Regulatory agencies are increasingly interested in risk-based approaches that demonstrate genuine process understanding and continuous improvement capabilities. Rhythmic quality risk management strengthens regulatory relationships by showing sophisticated thinking about process optimization and quality enhancement within established frameworks.

When communicating with regulatory agencies, emphasize how rhythmic approaches improve process understanding, enhance control strategy development, and support continuous improvement objectives. Show how structured flexibility leads to better patient protection through more responsive and adaptive quality systems.

Focus regulatory communications on how enhanced risk understanding leads to better quality outcomes rather than on operational efficiency benefits that might appear secondary to regulatory objectives. Demonstrate how rhythmic approaches maintain analytical rigor while enabling more effective responses to emerging quality challenges.

The Future of Quality Risk Management: Beyond Rhythm to Resonance

As we master rhythmic approaches to quality risk management, the next evolution involves what I call “quality resonance”—the phenomenon that occurs when individual quality rhythms align and amplify each other across organizational boundaries. Just as musical instruments can create resonance that produces sounds more powerful than any individual instrument, quality organizations can achieve resonant states where risk management effectiveness transcends the sum of individual contributions.

Resonant quality organizations share several characteristics:

- Synchronized Rhythm Networks: Quality rhythms in different departments, processes, and product lines align to create organization-wide patterns of risk awareness and response capability.

- Harmonic Risk Communication: Information flows between quality functions create harmonics that amplify important signals while filtering noise, enabling more effective decision-making at all organizational levels.

- Emergent Quality Intelligence: The interaction of multiple rhythmic quality processes generates insights and capabilities that wouldn’t be possible through individual efforts alone.

Building toward quality resonance requires sustained commitment to rhythmic principles, continuous refinement of quality cadences, and patient development of organizational capability. The payoff, however, is transformational: quality risk management that not only prevents problems but actively creates value through enhanced understanding, improved processes, and strengthened competitive position.

Finding Your Quality Beat

Uncertainty is inevitable in pharmaceutical manufacturing, regulatory environments, and global supply chains. As Hudson emphasizes, the choice is whether to exhaust ourselves trying to conduct every quality note or to lay down rhythms that enable entire teams to create something extraordinary together.

Tomorrow morning, when you walk into that risk assessment meeting, you’ll face this choice in real time. Will you pick up the conductor’s baton, trying to control every analytical voice? Or will you sit at the back of the stage and create the beat on which your quality team can find its flow?

The research is clear: rhythmic approaches to complex work create better outcomes, higher engagement, and more sustainable performance. The ICH Q9(R1) framework provides the flexibility needed to implement rhythmic quality risk management while maintaining regulatory compliance. The tools and techniques exist to transform quality risk management from a defensive necessity into an adaptive capability that drives innovation and competitive advantage.

The question isn’t whether rhythmic quality risk management will emerge—it’s whether your organization will lead this transformation or struggle to catch up. The teams that master quality rhythm first will be best positioned to thrive in our increasingly BANI pharmaceutical world, turning uncertainty into opportunity while maintaining the rigorous standards our patients deserve.

Start with one beat. Find one aspect of your current quality risk management where you can separate exploration from analysis, create space for reflection, or enable someone to lead. Feel the difference that rhythm makes. Then gradually expand, building the quality jazz ensemble that our complex manufacturing world demands.

The rhythm section is waiting. It’s time to find your quality beat.