Review of documents are a critical part of the document management lifecycle.

In the post Process/Procedure Lifecycle there are some fundamental stakeholders:

- The Process Owner defines the process, including people, process steps, and technology, as well as the connections to other processes. They are accountable for change management, training, monitoring and control of the process and supporting procedure. The Process Owners owns the continuous improvement of the overall process.

- Quality is ultimately responsible for the decisions made and that they align, at a minimum, with all regulatory requirements and internal standards.

- Functional Area Management represents the areas that have responsibilities in the process and has a vested interest or concern in the ongoing performance of a process. This can include stakeholders who are process owners in upstream or downstream processes.

- A Subject Matter Expert (SME) is typically an expert on a narrow division of a process, such as a specific tool, system, or set of process steps. A process may have multiple subject matter experts associated with it, each with varying degrees of understanding of the over-arching process.

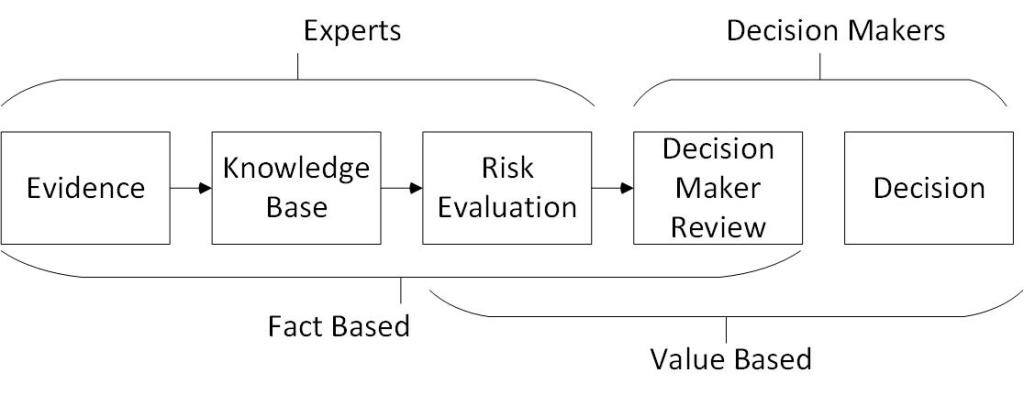

A Risk Based Approach

The level of review of a new or revised process/procedure is guided by three fundamental risk questions:

- What might go wrong with the associated process? (risk identification)

- What is the likelihood that this will go wrong? (risk analysis)

- What are the consequences? How severe are they if this goes wrong? (risk analysis)

Conducting risk identification is real about understanding how complicated and complex the associated process is. This looks at the following criteria:

- Interconnectedness: the organization and interaction of system components and other processes

- Repeatability: the amount of variance in the process

- Information content: the amount of information needed to interact with the process

What Happens During a Review of Process and Procedure

The review of a process/procedure ensures that the proposed changes add value to the process and attain the outcome the organization wants. There are three levels of review (which can and often do happen simultaneously):

- Functional review

- Expert review by subject matter experts

- Step-by-step real-world challenge

Functional review is the vetting of the process/procedure. Process stakeholders, including functional area management affected by the change has the opportunity to review the draft, suggest changes and agree to move forward.

Functional review supplies the lowest degree of assurance. This review looks for potential impact of the change on the function – usually focused on responsibilities – but does not necessarily assures a critical review.

In the case of expert review, the SMEs will review the draft for both positive and negative elements. On the positive side, they will look for the best practices, value-adding steps, flexibility in light of changing demands, scalability in light of changing output targets, etc. On the negative side, they will look for bottlenecks in the process, duplication of effort, unnecessary tasks, non-value-adding steps, role ambiguities (i.e. several positions responsible for a task, or no one responsible for a task), etc.

Expert review provides a higher degree of assurance because it is a compilation of expert opinion and it is focused on the technical content of the procedure.

The real-world challenge tests the process/procedure’s applicability by challenging it step-by-step in as much as possible the actual conditions of use. Tis involves selecting seasoned employee(s) within the scope of the draft procedure – not necessarily a SME – and comparing the steps as drafted with the actual activities. It is important to ascertain if they align. It is equally important to consider evidence of resistance, repetition and human factor problems.

Sometimes it can be more appropriate to do the real-world test as a tabletop or simulation exercise.

As sufficient reviews are obtained, the comments received are incorporated, as appropriate. Significant changes incorporated during the review process may require the procedure be re-routed for review, and may require the need to add additional reviews.

Repeat as a iterative process as necessary.

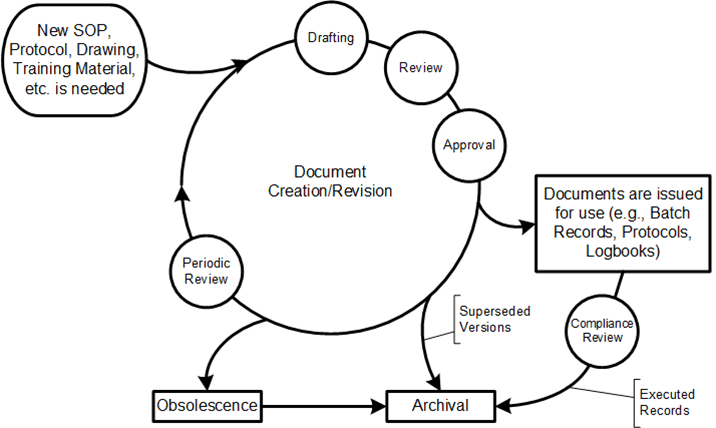

The process/procedure lifecycle can be seen as the iterative design lifecycle.

Design Thinking: Determine process needs.

- Collect and document business requirements

- Map current-state processes.

- Observe and interview process workers.

- Design process to-be.

Startup: Create process documentation, workflows, and support materials. Review and described above

Continuous Improvement: Use the process; Collect, analyze, and report; Improve