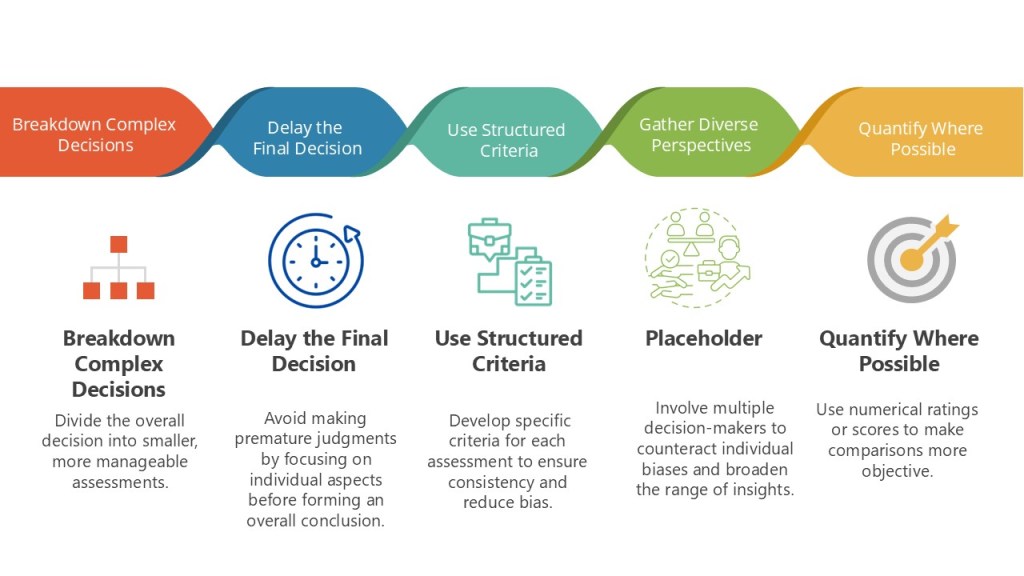

A building block of Quality culture is learning how to make decisions faster without impairing their quality. We do this by ensuring availability of the right knowledge so that the appropriate measures can be decided on and making the decision-making processes quicker.

Adopting a flexible but consistent approach to decision-making and giving people greater leeway creates the organizational framework for faster decision-making processes. In addition to creating the right framework, however, it is equally important for employees to have confidence in each other so that decisions are not only taken quickly but also implemented swiftly. Rather than merely seeing employees as resources, this requires management to value them as part of the community because of the competencies that they bring to the table. The underlying capability that makes this possible is a democratic leadership style.

Democratic leadership is a style where decision-making is decentralized and shared by all. This style of leadership proposes that decision-making should be shared by the leader and the group where criticisms and praises are objectively given and a feeling of responsibility is developed within the group. Leaders engage in dialogue that offers others the opportunity to use their initiative and make contributions. Once decisions are collectively taken, people are sure of what to do and how to do it with support from leaders to accomplish tasks successfully. It is the “Yes…but…and” style of leadership.

This style requires a high degree of effort in building organizational decision-making capabilities. You need to build a culture that ensures that everyone has an equal interest in an outcome and shared levels of expertise relative to decisions. But nothing provides better motivated employees.

For those keeping track on the leadership style bingo card, this requires mashing democratic and transformational leaders together (with a hefty flavoring of servant leadership). Just the democratic style is not enough, you need a few more aspects of a transformational leader to make it work.

Idealized Influence means being the role model and being seen to be accountable to the culture. Part of this is doing Gemba walks as part of your standard work.

Inspirational Motivation means inspiring confidence, motivation and a sense of purpose. The leader must articulate a clear vision for the future, communicate expectations of the group and demonstrate a commitment to the goals that have been decided upon.

Through Intellectual Stimulation, the leader presents to the organization a number of challenging new ideas that are supposed to stimulate rethinking of new ways of doing things in the organization, thus seeking ideas, opinions and inputs from others to promote creativity, innovation and experimentation of new methods to replace the old ways. The leader articulates True North.

Decentralized decision-making around these new ways of doing are shared by all. Decisions are taken by both the leader and the group where criticisms and praises are objectively given and a feeling of responsibility is developed within the group, thus granting everyone the opportunity to use their initiative and make contributions. Decentralized decision-making ensures everyone empowered to take actions and are responsible for the implementation and effectiveness of these actions. This will drive adaptation and bring accountability.

Reading list

- Arenas, F.J., Connelly, D.A. and Williams, M.D. (2018), Developing Your Full Range of Leadership, Air University Press, Maxwell AFB

- Gastil, J. (1994), “A definition and illustration of democratic leadership”, Human Relations, Vol. 47 No. 8,pp. 953-975

- Hayes, A.F. (2018), Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis, 2nd ed.,The Guilford Press, New York, N