When I encounter professionals who believe they can master a process in six months, I think of something the great systems thinker W. Edwards Deming once observed: “It is not necessary to change. Survival is not mandatory.” The professionals who survive—and more importantly, who drive genuine improvement—understand something that transcends the checkbox mentality: true ownership takes time, patience, and what some might call “stick-to-itness.”

The uncomfortable truth is that most of us confuse familiarity with mastery. We mistake the ability to execute procedures with the deep understanding required to improve them. This confusion has created a generation of professionals who move from role to role, collecting titles and experiences but never developing the profound process knowledge that enables breakthrough improvement. This is equally true on the consultant side.

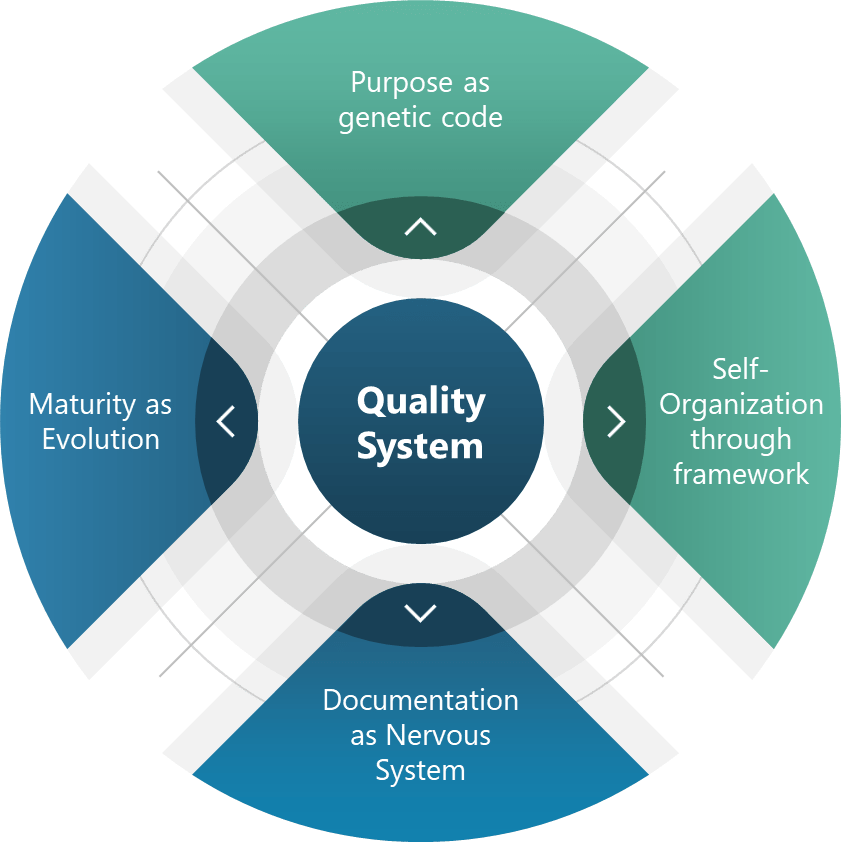

The cost of this superficial approach extends far beyond individual career trajectories. When organizations lack deep process owners—people who have lived with systems long enough to understand their subtle rhythms and hidden failure modes—they create what I call “quality theater”: elaborate compliance structures that satisfy auditors but fail to serve patients, customers, or the fundamental purpose of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The Science of Deep Ownership

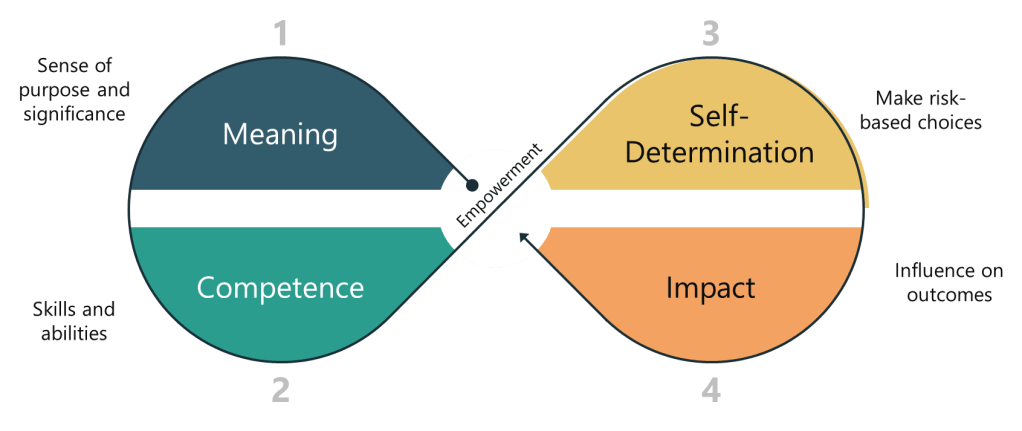

Recent research in organizational psychology reveals the profound difference between surface-level knowledge and genuine psychological ownership. When employees develop true psychological ownership of their processes, something remarkable happens: they begin to exhibit behaviors that extend far beyond their job descriptions. They proactively identify risks, champion improvements, and develop the kind of intimate process knowledge that enables predictive rather than reactive management.

But here’s what the research also shows: this psychological ownership doesn’t emerge overnight. Studies examining the relationship between tenure and performance consistently demonstrate nonlinear effects. The correlation between tenure and performance actually decreases exponentially over time—but this isn’t because long-tenured employees become less effective. Instead, it reflects the reality that deep expertise follows a complex curve where initial competence gives way to periods of plateau, followed by breakthrough understanding that emerges only after years of sustained engagement.

Consider the findings from meta-analyses of over 3,600 employees across various industries. The relationship between organizational commitment and job performance shows a very strong nonlinear moderating effect based on tenure. The implications are profound: the value of process ownership isn’t linear, and the greatest insights often emerge after years of what might appear to be steady-state performance.

This aligns with what quality professionals intuitively know but rarely discuss: the most devastating process failures often emerge from interactions and edge cases that only become visible after sustained observation. The process owner who has lived through multiple product campaigns, seasonal variations, and equipment lifecycle transitions develops pattern recognition that cannot be captured in procedures or training materials.

The 10,000 Hour Reality in Quality Systems

Malcolm Gladwell’s popularization of the 10,000-hour rule has been both blessing and curse for understanding expertise development. While recent research has shown that deliberate practice accounts for only 18-26% of skill variation—meaning other factors like timing, genetics, and learning environment matter significantly—the core insight remains valid: mastery requires sustained, focused engagement over years, not months.

But the pharmaceutical quality context adds layers of complexity that make the expertise timeline even more demanding. Unlike chess players or musicians who can practice their craft continuously, quality professionals must develop expertise within regulatory frameworks that change, across technologies that evolve, and through organizational transitions that reset context. The “hours” of meaningful practice are often interrupted by compliance activities, reorganizations, and role changes that fragment the learning experience.

More importantly, quality expertise isn’t just about individual skill development—it’s about understanding systems. Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge emphasizes that effective quality management requires appreciation for a system, knowledge about variation, theory of knowledge, and psychology. This multidimensional expertise cannot be compressed into abbreviated timelines, regardless of individual capability or organizational urgency.

The research on mastery learning provides additional insight. True mastery-based approaches require that students achieve deep understanding at each level before progressing to the next. In quality systems, this means that process owners must genuinely understand the current state of their processes—including their failure modes, sources of variation, and improvement potential—before they can effectively drive transformation.

The Hidden Complexity of Process Ownership

Many of our organizations struggle with “iceberg phenomenon”: the visible aspects of process ownership—procedure compliance, metric reporting, incident response—represent only a small fraction of the role’s true complexity and value.

Effective process owners develop several types of knowledge that accumulate over time:

- Tacit Process Knowledge: Understanding the subtle indicators that precede process upsets, the informal workarounds that maintain operations, and the human factors that influence process performance. This knowledge emerges through repeated exposure to process variations and cannot be documented or transferred through training.

- Systemic Understanding: Comprehending how their process interacts with upstream and downstream activities, how changes in one area create ripple effects throughout the system, and how to navigate the political and technical constraints that shape improvement opportunities. This requires exposure to multiple improvement cycles and organizational changes.

- Regulatory Intelligence: Developing nuanced understanding of how regulatory expectations apply to their specific context, how to interpret evolving guidance, and how to balance compliance requirements with operational realities. This expertise emerges through regulatory interactions, inspection experiences, and industry evolution.

- Change Leadership Capability: Building the credibility, relationships, and communication skills necessary to drive improvement in complex organizational environments. This requires sustained engagement with stakeholders, demonstrated success in previous initiatives, and deep understanding of organizational dynamics.

Each of these knowledge domains requires years to develop, and they interact synergistically. The process owner who has lived through equipment upgrades, regulatory inspections, organizational changes, and improvement initiatives develops a form of professional judgment that cannot be replicated through rotation or abbreviated assignments.

The Deming Connection: Systems Thinking Requires Time

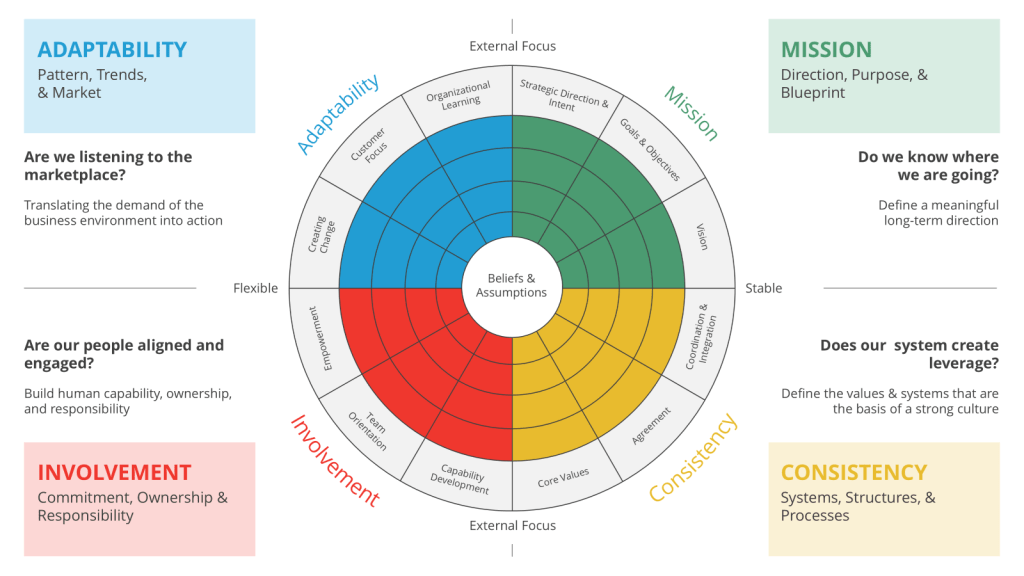

Deming’s philosophy of continuous improvement provides a crucial framework for understanding why process ownership requires sustained engagement. His approach to quality was holistic, emphasizing systems thinking and long-term perspective over quick fixes and individual blame.

Consider Deming’s first point: “Create constancy of purpose toward improvement of product and service.” This isn’t about maintaining consistency in procedures—it’s about developing the deep understanding necessary to identify genuine improvement opportunities rather than cosmetic changes that satisfy short-term pressures.

The PDCA cycle that underlies Deming’s approach explicitly requires iterative learning over multiple cycles. Each cycle builds on previous learning, and the most valuable insights often emerge after several iterations when patterns become visible and root causes become clear. Process owners who remain with their systems long enough to complete multiple cycles develop qualitatively different understanding than those who implement single improvements and move on.

Deming’s emphasis on driving out fear also connects to the tenure question. Organizations that constantly rotate process owners signal that deep expertise isn’t valued, creating environments where people focus on short-term achievements rather than long-term system health. The psychological safety necessary for honest problem-solving and innovative improvement requires stable relationships built over time.

The Current Context: Why Stick-to-itness is Endangered

The pharmaceutical industry’s current talent management practices work against the development of deep process ownership. Organizations prioritize broad exposure over deep expertise, encourage frequent role changes to accelerate career progression, and reward visible achievements over sustained system stewardship.

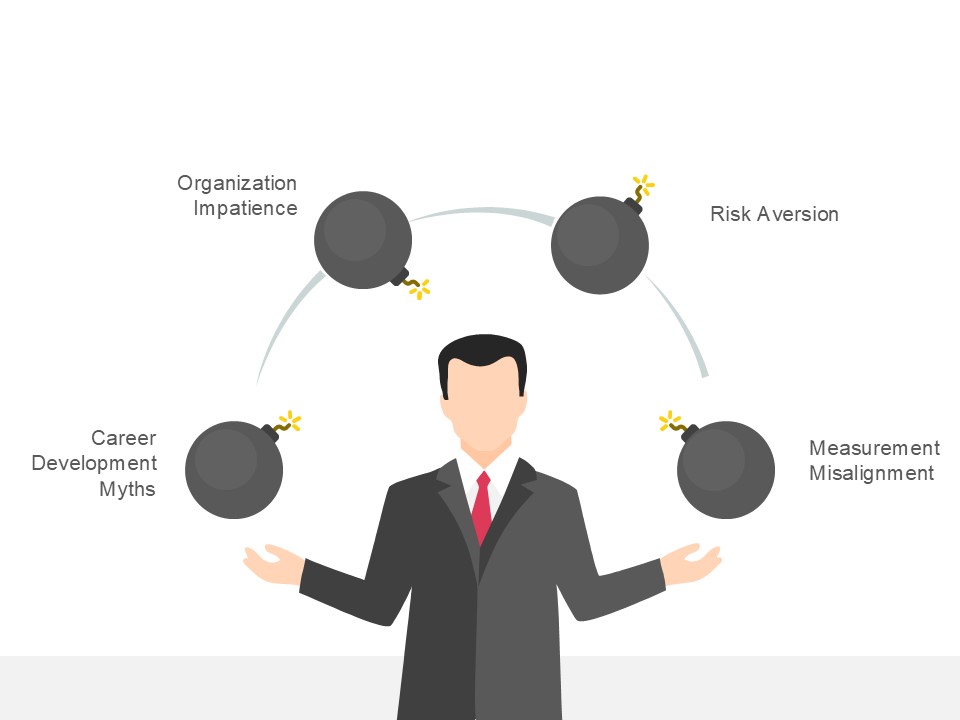

This approach has several drivers, most of them understandable but ultimately counterproductive:

- Career Development Myths: The belief that career progression requires constant role changes, preventing the development of deep expertise in any single area. This creates professionals with broad but shallow knowledge who lack the depth necessary to drive breakthrough improvement.

- Organizational Impatience: Pressure to demonstrate rapid improvement, leading to premature conclusions about process owner effectiveness and frequent role changes before mastery can develop. This prevents organizations from realizing the compound benefits of sustained process ownership.

- Risk Aversion: Concern that deep specialization creates single points of failure, leading to policies that distribute knowledge across multiple people rather than developing true expertise. This approach reduces organizational vulnerability to individual departures but eliminates the possibility of breakthrough improvement that requires deep understanding.

- Measurement Misalignment: Performance management systems that reward visible activity over sustained stewardship, creating incentives for process owners to focus on quick wins rather than long-term system development.

The result is what I observe throughout the industry: sophisticated quality systems managed by well-intentioned professionals who lack the deep process knowledge necessary to drive genuine improvement. We have created environments where people are rewarded for managing systems they don’t truly understand, leading to the elaborate compliance theater that satisfies auditors but fails to protect patients.

Building Genuine Process Ownership Capability

Creating conditions for deep process ownership requires intentional organizational design that supports sustained engagement rather than constant rotation. This isn’t about keeping people in the same roles indefinitely—it’s about creating career paths that value depth alongside breadth and recognize the compound benefits of sustained expertise development.

Redefining Career Success: Organizations must develop career models that reward deep expertise alongside traditional progression. This means creating senior individual contributor roles, recognizing process mastery in compensation and advancement decisions, and celebrating sustained system stewardship as a form of leadership.

Supporting Long-term Engagement: Process owners need organizational support to sustain motivation through the inevitable plateaus and frustrations of deep system work. This includes providing resources for continuous learning, connecting them with external expertise, and ensuring their contributions are visible to senior leadership.

Creating Learning Infrastructure: Deep process ownership requires systematic approaches to knowledge capture, reflection, and improvement. Organizations must provide time and tools for process owners to document insights, conduct retrospective analyses, and share learning across the organization.

Building Technical Career Paths: The industry needs career models that allow technical professionals to advance without moving into management roles that distance them from process ownership. This requires creating parallel advancement tracks, appropriate compensation structures, and recognition systems that value technical leadership.

Measuring Long-term Value: Performance management systems must evolve to recognize the compound benefits of sustained process ownership. This means developing metrics that capture system stability, improvement consistency, and knowledge development rather than focusing exclusively on short-term achievements.

The Connection to Jobs-to-Be-Done

The Jobs-to-Be-Done tool I explored iprovides valuable insight into why process ownership requires sustained engagement. Organizations don’t hire process owners to execute procedures—they hire them to accomplish several complex jobs that require deep system understanding:

Knowledge Development: Building comprehensive understanding of process behavior, failure modes, and improvement opportunities that enables predictive rather than reactive management.

System Stewardship: Maintaining process health through minor adjustments, preventive actions, and continuous optimization that prevents major failures and enables consistent performance.

Change Leadership: Driving improvements that require deep technical understanding, stakeholder engagement, and change management capabilities developed through sustained experience.

Organizational Memory: Serving as repositories of process history, lessons learned, and contextual knowledge that prevents the repetition of past mistakes and enables informed decision-making.

Each of these jobs requires sustained engagement to accomplish effectively. The process owner who moves to a new role after 18 months may have learned the procedures, but they haven’t developed the deep understanding necessary to excel at these higher-order responsibilities.

The Path Forward: Embracing the Long View

We need to fundamentally rethink how we develop and deploy process ownership capability in pharmaceutical quality systems. This means acknowledging that true expertise takes time, creating organizational conditions that support sustained engagement, and recognizing the compound benefits of deep process knowledge.

The choice is clear: continue cycling process owners through abbreviated assignments that prevent the development of genuine expertise, or build career models and organizational practices that enable deep process ownership to flourish. In an industry where process failures can result in patient harm, product recalls, and regulatory action, only the latter approach offers genuine protection.

True process ownership isn’t something we implement because best practices require it. It’s a capability we actively cultivate because it makes us demonstrably better at protecting patients and ensuring product quality. When we design organizational systems around the jobs that deep process ownership accomplishes—knowledge development, system stewardship, change leadership, and organizational memory—we create competitive advantages that extend far beyond compliance.

Organizations that recognize the value of sustained process ownership and create conditions for its development will build capabilities that enable breakthrough improvement and genuine competitive advantage. Those that continue to treat process ownership as a rotational assignment will remain trapped in the cycle of elaborate compliance theater that satisfies auditors but fails to serve the fundamental purpose of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Process ownership should not be something we implement because organizational charts require it. It should be a capability we actively develop because it makes us demonstrably better at the work that matters: protecting patients, ensuring product quality, and advancing the science of pharmaceutical manufacturing. When we embrace the deep ownership paradox—that mastery requires time, patience, and sustained engagement—we create the conditions for the kind of breakthrough improvement that our industry desperately needs.

In quality systems, as in life, the most valuable capabilities cannot be rushed, shortcuts cannot be taken, and true expertise emerges only through sustained engagement with the work that matters. This isn’t just good advice for individual career development—it’s the foundation for building pharmaceutical quality systems that genuinely serve patients and advance human health.

Further Reading

Kausar, F., Ijaz, M. U., Rasheed, M., Suhail, A., & Islam, U. (2025). Empowered, accountable, and committed? Applying self-determination theory to examine work-place procrastination. BMC Psychology, 13, 620. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02968-7

Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12144702/

Kim, A. J., & Chung, M.-H. (2023). Psychological ownership and ambivalent employee behaviors: A moderated mediation model. SAGE Open, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231162535

Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/21582440231162535

Wright, T. A., & Bonett, D. G. (2002). The moderating effects of employee tenure on the relation between organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1183-1190. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1183

Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12558224/