I think we all have a central challenge in our professional life: How do we distinguish between genuine scientific insights that enhance our practice and the seductive allure of popularized psychological concepts that promise quick fixes but deliver questionable results. This tension between rigorous evidence and intuitive appeal represents more than an academic debate, it strikes at the heart of our professional identity and effectiveness.

The emergence of emotional intelligence as a dominant workplace paradigm exemplifies this challenge. While interpersonal skills undoubtedly matter in quality management, the uncritical adoption of psychological frameworks without scientific scrutiny creates what Dave Snowden aptly terms the “Woozle effect”—a phenomenon where repeated citation transforms unvalidated concepts into accepted truth. As quality thinkers, we must navigate this landscape with both intellectual honesty and practical wisdom, building systems that honor the genuine insights about human behavior while maintaining rigorous standards for evidence.

This exploration connects directly to the cognitive foundations of risk management excellence we’ve previously examined. The same systematic biases that compromise risk assessments—confirmation bias, anchoring effects, and overconfidence—also make us vulnerable to appealing but unsubstantiated management theories. By understanding these connections, we can develop more robust approaches that integrate the best of scientific evidence with the practical realities of human interaction in quality systems.

The Seductive Appeal of Pop Psychology in Quality Management

The proliferation of psychological concepts in business environments reflects a genuine need. Quality professionals recognize that technical competence alone cannot ensure organizational success. We need effective communication, collaborative problem-solving, and the ability to navigate complex human dynamics. This recognition creates fertile ground for frameworks that promise to unlock the mysteries of human behavior and transform our organizational effectiveness.

However, the popularity of concepts like emotional intelligence often stems from their intuitive appeal rather than their scientific rigor. As Professor Merve Emre’s critique reveals, such frameworks can become “morality plays for a secular era, performed before audiences of mainly white professionals”. They offer the comfortable illusion of control over complex interpersonal dynamics while potentially obscuring more fundamental issues of power, inequality, and systemic dysfunction.

The quality profession’s embrace of these concepts reflects our broader struggle with what researchers call “pseudoscience at work”. Despite our commitment to evidence-based thinking in technical domains, we can fall prey to the same cognitive biases that affect other professionals. The competitive nature of modern quality management creates pressure to adopt the latest insights, leading us to embrace concepts that feel innovative and transformative without subjecting them to the same scrutiny we apply to our technical methodologies.

This phenomenon becomes particularly problematic when we consider the Woozle effect in action. Dave Snowden’s analysis demonstrates how concepts can achieve credibility through repeated citation rather than empirical validation. In the echo chambers of professional conferences and business literature, unvalidated theories gain momentum through repetition, eventually becoming embedded in our standard practices despite lacking scientific foundation.

The Cognitive Architecture of Quality Decision-Making

Understanding why quality professionals become susceptible to popularized psychological concepts requires examining the cognitive architecture underlying our decision-making processes. The same mechanisms that enable our technical expertise can also create vulnerabilities when applied to interpersonal and organizational challenges.

Our professional training emphasizes systematic thinking, data-driven analysis, and evidence-based conclusions. These capabilities serve us well in technical domains where variables can be controlled and measured. However, when confronting the messier realities of human behavior and organizational dynamics, we may unconsciously lower our evidentiary standards, accepting frameworks that align with our intuitions rather than demanding the same level of proof we require for technical decisions.

This shift reflects what cognitive scientists call “domain-specific expertise limitations.” Our deep knowledge in quality systems doesn’t automatically transfer to psychology or organizational behavior. Yet our confidence in our technical judgment can create overconfidence in our ability to evaluate non-technical concepts, leading to what researchers identify as a key vulnerability in professional decision-making.

The research on cognitive biases in professional settings reveals consistent patterns across management, finance, medicine, and law. Overconfidence emerges as the most pervasive bias, leading professionals to overestimate their ability to evaluate evidence outside their domain of expertise. In quality management, this might manifest as quick adoption of communication frameworks without questioning their empirical foundation, or assuming that our systematic thinking skills automatically extend to understanding human psychology.

Confirmation bias compounds this challenge by leading us to seek information that supports our preferred approaches while ignoring contradictory evidence. If we find an interpersonal framework appealing, perhaps because it aligns with our values or promises to solve persistent challenges, we may unconsciously filter available information to support our conclusion. This creates the self-reinforcing cycles that allow questionable concepts to become embedded in our practice.

Evidence-Based Approaches to Interpersonal Effectiveness

The solution to the pop psychology problem doesn’t lie in dismissing the importance of interpersonal skills or communication effectiveness. Instead, it requires applying the same rigorous standards to behavioral insights that we apply to technical knowledge. This means moving beyond frameworks that merely feel right toward approaches grounded in systematic research and validated through empirical study.

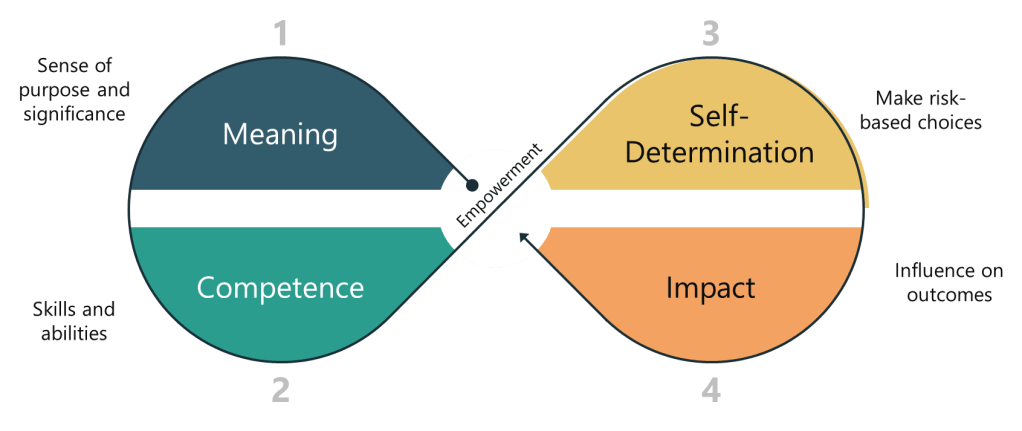

Evidence-based management provides a framework for navigating this challenge. Rather than relying solely on intuition, tradition, or popular trends, evidence-based approaches emphasize the systematic use of four sources of evidence: scientific literature, organizational data, professional expertise, and stakeholder perspectives. This framework enables us to evaluate interpersonal and communication concepts with the same rigor we apply to technical decisions.

Scientific literature offers the most robust foundation for understanding interpersonal effectiveness. Research in organizational psychology, communication science, and related fields provides extensive evidence about what actually works in workplace interactions. For example, studies on psychological safety demonstrate clear relationships between specific leadership behaviors and team performance outcomes. This research enables us to move beyond generic concepts like “emotional intelligence” toward specific, actionable insights about creating environments where teams can perform effectively.

Organizational data provides another crucial source of evidence for evaluating interpersonal approaches. Rather than assuming that communication training programs or team-building initiatives are effective, we can measure their actual impact on quality outcomes, employee engagement, and organizational performance. This data-driven approach helps distinguish between interventions that feel good and those that genuinely improve results.

Professional expertise remains valuable, but it must be systematically captured and validated rather than simply accepted as received wisdom. This means documenting the reasoning behind successful interpersonal approaches, testing assumptions about what works, and creating mechanisms for updating our understanding as new evidence emerges. The risk management excellence framework we’ve previously explored provides a model for this systematic approach to knowledge management.

The Integration Challenge: Systematic Thinking Meets Human Reality

The most significant challenge facing quality professionals lies in integrating rigorous, evidence-based approaches with the messy realities of human interaction. Technical systems can be optimized through systematic analysis and controlled improvement, but human systems involve emotions, relationships, and cultural dynamics that resist simple optimization approaches.

This integration challenge requires what we might call “systematic humility“—the recognition that our technical expertise creates capabilities but also limitations. We can apply systematic thinking to interpersonal challenges, but we must acknowledge the increased uncertainty and complexity involved. This doesn’t mean abandoning rigor; instead, it means adapting our approaches to acknowledge the different evidence standards and validation methods required for human-centered interventions.

The cognitive foundations of risk management excellence provide a useful model for this integration. Just as effective risk management requires combining systematic analysis with recognition of cognitive limitations, effective interpersonal approaches require combining evidence-based insights with acknowledgment of human complexity. We can use research on communication effectiveness, team dynamics, and organizational behavior to inform our approaches while remaining humble about the limitations of our knowledge.

One practical approach involves treating interpersonal interventions as experiments rather than solutions. Instead of implementing communication training programs or team-building initiatives based on popular frameworks, we can design systematic pilots that test specific hypotheses about what will improve outcomes in our particular context. This experimental approach enables us to learn from both successes and failures while building organizational knowledge about what actually works.

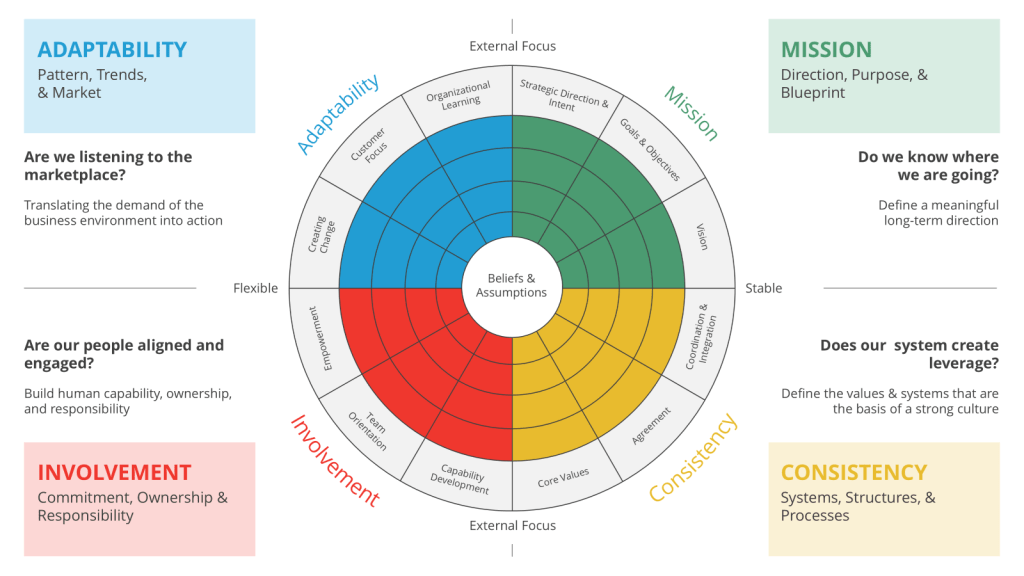

The systems thinking perspective offers another valuable framework for integration. Rather than viewing interpersonal skills as individual capabilities separate from technical systems, we can understand them as components of larger organizational systems. This perspective helps us recognize how communication patterns, relationship dynamics, and cultural factors interact with technical processes to influence quality outcomes.

Systems thinking also emphasizes feedback loops and emergent properties that can’t be predicted from individual components. In interpersonal contexts, this means recognizing that the effectiveness of communication approaches depends on context, relationships, and organizational culture in ways that may not be immediately apparent. This systemic perspective encourages more nuanced approaches that consider the broader organizational ecosystem rather than assuming that generic interpersonal frameworks will work universally.

Building Knowledge-Enabled Quality Systems

The path forward requires developing what we can call “knowledge-enabled quality systems“—organizational approaches that systematically integrate evidence about both technical and interpersonal effectiveness while maintaining appropriate skepticism about unvalidated claims. These systems combine the rigorous analysis we apply to technical challenges with equally systematic approaches to understanding and improving human dynamics.

Knowledge-enabled systems begin with systematic evidence requirements that apply across all domains of quality management. Whether evaluating a new measurement technology or a communication framework, we should require similar levels of evidence about effectiveness, limitations, and appropriate application contexts. This doesn’t mean identical evidence—the nature of proof differs between technical and behavioral domains—but it does mean consistent standards for what constitutes adequate justification for adopting new approaches.

These systems also require structured approaches to capturing and validating organizational knowledge about interpersonal effectiveness. Rather than relying on informal networks or individual expertise, we need systematic methods for documenting what works in specific contexts, testing assumptions about effective approaches, and updating our understanding as conditions change. The knowledge management principles discussed in our risk management excellence framework provide a foundation for these systematic approaches.

Cognitive bias mitigation becomes particularly important in knowledge-enabled systems because the stakes of interpersonal decisions can be as significant as technical ones. Poor communication can undermine the best technical solutions, while ineffective team dynamics can prevent organizations from identifying and addressing quality risks. This means applying the same systematic approaches to bias recognition and mitigation that we use in technical risk assessment.

The development of these systems requires what we might call “transdisciplinary competence”—the ability to work effectively across technical and behavioral domains while maintaining appropriate standards for evidence and validation in each. This competence involves understanding the different types of evidence available in different domains, recognizing the limitations of our expertise across domains, and developing systematic approaches to learning and validation that work across different types of challenges.

From Theory to Organizational Reality

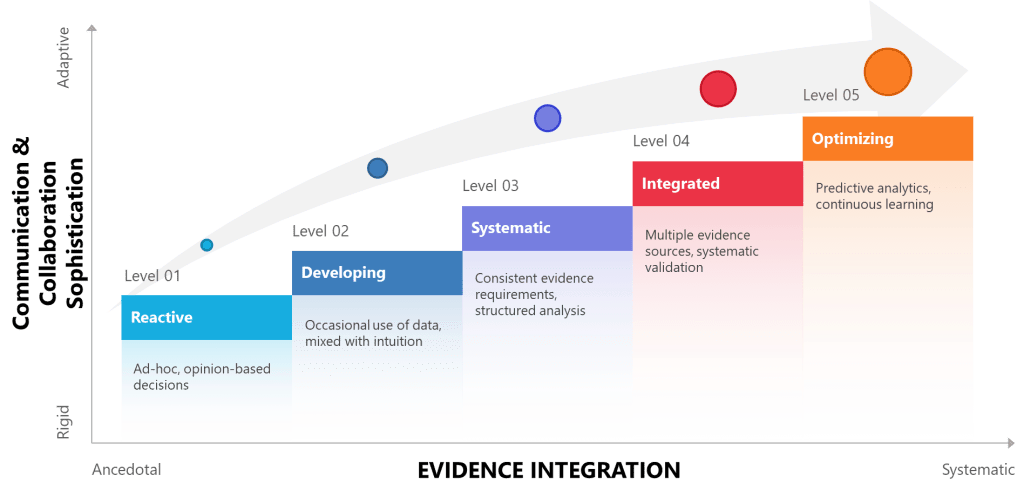

Translating these concepts into practical organizational improvements requires systematic approaches that can be implemented incrementally while building toward more comprehensive transformation. The maturity model framework provides a useful structure for understanding this progression.

| Cognitive Bias | Quality Impact | Communication Manifestation | Evidence-Based Countermeasure |

| Confirmation Bias | Cherry-picking data that supports existing beliefs | Dismissing challenging feedback from teams | Structured devil’s advocate processes |

| Anchoring Bias | Over-relying on initial risk assessments | Setting expectations based on limited initial information | Multiple perspective requirements |

| Availability Bias | Focusing on recent/memorable incidents over data patterns | Emphasizing dramatic failures over systematic trends | Data-driven trend analysis over anecdotes |

| Overconfidence Bias | Underestimating uncertainty in complex systems | Overestimating ability to predict team responses | Confidence intervals and uncertainty quantification |

| Groupthink | Suppressing dissenting views in risk assessments | Avoiding difficult conversations to maintain harmony | Diverse team composition and external review |

| Sunk Cost Fallacy | Continuing ineffective programs due to past investment | Defending communication strategies despite poor results | Regular program evaluation with clear exit criteria |

Organizations beginning this journey typically operate at the reactive level, where interpersonal approaches are adopted based on popularity, intuition, or immediate perceived need rather than systematic evaluation. Moving toward evidence-based interpersonal effectiveness requires progressing through increasingly sophisticated approaches to evidence gathering, validation, and integration.

The developing level involves beginning to apply evidence standards to interpersonal approaches while maintaining flexibility about the types of evidence required. This might include piloting communication frameworks with clear success metrics, gathering feedback data about team effectiveness initiatives, or systematically documenting the outcomes of different approaches to stakeholder engagement.

Systematic-level organizations develop formal processes for evaluating and implementing interpersonal interventions with the same rigor applied to technical improvements. This includes structured approaches to literature review, systematic pilot design, clear success criteria, and documented decision rationales. At this level, organizations treat interpersonal effectiveness as a systematic capability rather than a collection of individual skills.

| Domain | Scientific Foundation | Interpersonal Application | Quality Outcome |

| Risk Assessment | Systematic hazard analysis, quantitative modeling | Collaborative assessment teams, stakeholder engagement | Comprehensive risk identification, bias-resistant decisions |

| Team Communication | Communication effectiveness research, feedback metrics | Active listening, psychological safety, conflict resolution | Enhanced team performance, reduced misunderstandings |

| Process Improvement | Statistical process control, designed experiments | Cross-functional problem solving, team-based implementation | Sustainable improvements, organizational learning |

| Training & Development | Learning theory, competency-based assessment | Mentoring, peer learning, knowledge transfer | Competent workforce, knowledge retention |

| Performance Management | Behavioral analytics, objective measurement | Regular feedback conversations, development planning | Motivated teams, continuous improvement mindset |

| Change Management | Change management research, implementation science | Stakeholder alignment, resistance management, culture building | Successful transformation, organizational resilience |

Integration-level organizations embed evidence-based approaches to interpersonal effectiveness throughout their quality systems. Communication training becomes part of comprehensive competency development programs grounded in learning science. Team dynamics initiatives connect directly to quality outcomes through systematic measurement and feedback. Stakeholder engagement approaches are selected and refined based on empirical evidence about effectiveness in specific contexts.

The optimizing level involves sophisticated approaches to learning and adaptation that treat both technical and interpersonal challenges as part of integrated quality systems. Organizations at this level use predictive analytics to identify potential interpersonal challenges before they impact quality outcomes, apply systematic approaches to cultural change and development, and contribute to broader professional knowledge about effective integration of technical and behavioral approaches.

| Level | Approach to Evidence | Interpersonal Communication | Risk Management | Knowledge Management |

| 1 – Reactive | Ad-hoc, opinion-based decisions | Relies on traditional hierarchies, informal networks | Reactive problem-solving, limited risk awareness | Tacit knowledge silos, informal transfer |

| 2 – Developing | Occasional use of data, mixed with intuition | Recognizes communication importance, limited training | Basic risk identification, inconsistent mitigation | Basic documentation, limited sharing |

| 3 – Systematic | Consistent evidence requirements, structured analysis | Structured communication protocols, feedback systems | Formal risk frameworks, documented processes | Systematic capture, organized repositories |

| 4 – Integrated | Multiple evidence sources, systematic validation | Culture of open dialogue, psychological safety | Integrated risk-communication systems, cross-functional teams | Dynamic knowledge networks, validated expertise |

| 5 – Optimizing | Predictive analytics, continuous learning | Adaptive communication, real-time adjustment | Anticipatory risk management, cognitive bias monitoring | Self-organizing knowledge systems, AI-enhanced insights |

Cognitive Bias Recognition and Mitigation in Practice

Understanding cognitive biases intellectually is different from developing practical capabilities to recognize and address them in real-world quality management situations. The research on professional decision-making reveals that even when people understand cognitive biases conceptually, they often fail to recognize them in their own decision-making processes.

This challenge requires systematic approaches to bias recognition and mitigation that can be embedded in routine quality management processes. Rather than relying on individual awareness or good intentions, we need organizational systems that prompt systematic consideration of potential biases and provide structured approaches to counter them.

The development of bias-resistant processes requires understanding the specific contexts where different biases are most likely to emerge. Confirmation bias becomes particularly problematic when evaluating approaches that align with our existing beliefs or preferences. Anchoring bias affects situations where initial information heavily influences subsequent analysis. Availability bias impacts decisions where recent or memorable experiences overshadow systematic data analysis.

Effective countermeasures must be tailored to specific biases and integrated into routine processes rather than applied as separate activities. Devil’s advocate processes work well for confirmation bias but may be less effective for anchoring bias, which requires multiple perspective requirements and systematic questioning of initial assumptions. Availability bias requires structured approaches to data analysis that emphasize patterns over individual incidents.

The key insight from cognitive bias research is that awareness alone is insufficient for bias mitigation. Effective approaches require systematic processes that make bias recognition routine and provide concrete steps for addressing identified biases. This means embedding bias checks into standard procedures, training teams in specific bias recognition techniques, and creating organizational cultures that reward systematic thinking over quick decision-making.

The Future of Evidence-Based Quality Practice

The evolution toward evidence-based quality practice represents more than a methodological shift—it reflects a fundamental maturation of our profession. As quality management becomes increasingly complex and consequential, we must develop more sophisticated approaches to distinguishing between genuine insights and appealing but unsubstantiated concepts.

This evolution requires what we might call “methodological pluralism”—the recognition that different types of questions require different approaches to evidence gathering and validation while maintaining consistent standards for rigor and critical evaluation. Technical questions can often be answered through controlled experiments and statistical analysis, while interpersonal effectiveness may require ethnographic study, longitudinal observation, and systematic case analysis.

The development of this methodological sophistication will likely involve closer collaboration between quality professionals and researchers in organizational psychology, communication science, and related fields. Rather than adopting popularized versions of behavioral insights, we can engage directly with the underlying research to understand both the validated findings and their limitations.

Technology will play an increasingly important role in enabling evidence-based approaches to interpersonal effectiveness. Communication analytics can provide objective data about information flow and interaction patterns. Sentiment analysis and engagement measurement can offer insights into the effectiveness of different approaches to stakeholder communication. Machine learning can help identify patterns in organizational behavior that might not be apparent through traditional analysis.

However, technology alone cannot address the fundamental challenge of developing organizational cultures that value evidence over intuition, systematic analysis over quick solutions, and intellectual humility over overconfident assertion. This cultural transformation requires leadership commitment, systematic training, and organizational systems that reinforce evidence-based thinking across all domains of quality management.

Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management

The systematic integration of evidence-based approaches to interpersonal effectiveness requires sophisticated approaches to organizational learning that can capture insights from both technical and behavioral domains while maintaining appropriate standards for validation and application.

Traditional approaches to organizational learning often treat interpersonal insights as informal knowledge that spreads through networks and mentoring relationships. While these mechanisms have value, they also create vulnerabilities to the transmission of unvalidated concepts and the perpetuation of approaches that feel effective but lack empirical support.

Evidence-based organizational learning requires systematic approaches to capturing, validating, and disseminating insights about interpersonal effectiveness. This includes documenting the reasoning behind successful communication approaches, testing assumptions about what works in different contexts, and creating systematic mechanisms for updating understanding as new evidence emerges.

The knowledge management principles from our risk management excellence work provide a foundation for these systematic approaches. Just as effective risk management requires systematic capture and validation of technical knowledge, effective interpersonal approaches require similar systems for behavioral insights. This means creating repositories of validated communication approaches, systematic documentation of context-specific effectiveness, and structured approaches to knowledge transfer and application.

One particularly important aspect of this knowledge management involves tacit knowledge: the experiential insights that effective practitioners develop but often cannot articulate explicitly. While tacit knowledge has value, it also creates vulnerabilities when it embeds unvalidated assumptions or biases. Systematic approaches to making tacit knowledge explicit enable organizations to subject experiential insights to the same validation processes applied to other forms of evidence.

The development of effective knowledge management systems also requires recognition of the different types of evidence available in interpersonal domains. Unlike technical knowledge, which can often be validated through controlled experiments, behavioral insights may require longitudinal observation, systematic case analysis, or ethnographic study. Organizations need to develop competencies in evaluating these different types of evidence while maintaining appropriate standards for validation and application.

Measurement and Continuous Improvement

The application of evidence-based approaches to interpersonal effectiveness requires sophisticated measurement systems that can capture both qualitative and quantitative aspects of communication, collaboration, and organizational culture while avoiding the reductionism that can make measurement counterproductive.

Traditional quality metrics focus on technical outcomes that can be measured objectively and tracked over time. Interpersonal effectiveness involves more complex phenomena that may require different measurement approaches while maintaining similar standards for validity and reliability. This includes developing metrics that capture communication effectiveness, team performance, stakeholder satisfaction, and cultural indicators while recognizing the limitations and potential unintended consequences of measurement systems.

One promising approach involves what researchers call “multi-method assessment”—the use of multiple measurement techniques to triangulate insights about interpersonal effectiveness. This might include quantitative metrics like response times and engagement levels, qualitative assessment through systematic observation and feedback, and longitudinal tracking of relationship quality and collaboration effectiveness.

The key insight from measurement research is that effective metrics must balance precision with validity—the ability to capture what actually matters rather than just what can be easily measured. In interpersonal contexts, this often means accepting greater measurement uncertainty in exchange for metrics that better reflect the complex realities of human interaction and organizational culture.

Continuous improvement in interpersonal effectiveness also requires systematic approaches to experimentation and learning that can test specific hypotheses about what works while building broader organizational capabilities over time. This experimental approach treats interpersonal interventions as systematic tests of specific assumptions rather than permanent solutions, enabling organizations to learn from both successes and failures while building knowledge about what works in their particular context.

Integration with the Quality System

The ultimate goal of evidence-based approaches to interpersonal effectiveness is not to create separate systems for behavioral and technical aspects of quality management, but to develop integrated approaches that recognize the interconnections between technical excellence and interpersonal effectiveness.

This integration requires understanding how communication patterns, relationship dynamics, and cultural factors interact with technical processes to influence quality outcomes. Poor communication can undermine the best technical solutions, while ineffective stakeholder engagement can prevent organizations from identifying and addressing quality risks. Conversely, technical problems can create interpersonal tensions that affect team performance and organizational culture.

Systems thinking provides a valuable framework for understanding these interconnections. Rather than treating technical and interpersonal aspects as separate domains, systems thinking helps us recognize how they function as components of larger organizational systems with complex feedback loops and emergent properties.

This systematic perspective also helps us avoid the reductionism that can make both technical and interpersonal approaches less effective. Technical solutions that ignore human factors often fail in implementation, while interpersonal approaches that ignore technical realities may improve relationships without enhancing quality outcomes. Integrated approaches recognize that sustainable quality improvement requires attention to both technical excellence and the human systems that implement and maintain technical solutions.

The development of integrated approaches requires what we might call “transdisciplinary competence”—the ability to work effectively across technical and behavioral domains while maintaining appropriate standards for evidence and validation in each. This competence involves understanding the different types of evidence available in different domains, recognizing the limitations of expertise across domains, and developing systematic approaches to learning and validation that work across different types of challenges.

Building Professional Maturity Through Evidence-Based Practice

The challenge of distinguishing between genuine scientific insights and popularized psychological concepts represents a crucial test of our profession’s maturity. As quality management becomes increasingly complex and consequential, we must develop more sophisticated approaches to evidence evaluation that can work across technical and interpersonal domains while maintaining consistent standards for rigor and validation.

This evolution requires moving beyond the comfortable dichotomy between technical expertise and interpersonal skills toward integrated approaches that apply systematic thinking to both domains. We must develop capabilities to evaluate behavioral insights with the same rigor we apply to technical knowledge while recognizing the different types of evidence and validation methods required in each domain.

The path forward involves building organizational cultures that value evidence over intuition, systematic analysis over quick solutions, and intellectual humility over overconfident assertion. This cultural transformation requires leadership commitment, systematic training, and organizational systems that reinforce evidence-based thinking across all aspects of quality management.

The cognitive foundations of risk management excellence provide a model for this evolution. Just as effective risk management requires systematic approaches to bias recognition and knowledge validation, effective interpersonal practice requires similar systematic approaches adapted to the complexities of human behavior and organizational culture.

The ultimate goal is not to eliminate the human elements that make quality management challenging and rewarding, but to develop more sophisticated ways of understanding and working with human reality while maintaining the intellectual honesty and systematic thinking that define our profession at its best. This represents not a rejection of interpersonal effectiveness, but its elevation to the same standards of evidence and validation that characterize our technical practice.

As we continue to evolve as a profession, our ability to navigate the evidence-practice divide will determine whether we develop into sophisticated practitioners capable of addressing complex challenges with both technical excellence and interpersonal effectiveness, or remain vulnerable to the latest trends and popularized concepts that promise easy solutions to difficult problems. The choice, and the opportunity, remains ours to make.

The future of quality management depends not on choosing between technical rigor and interpersonal effectiveness, but on developing integrated approaches that bring the best of both domains together in service of genuine organizational improvement and sustainable quality excellence. This integration requires ongoing commitment to learning, systematic approaches to evidence evaluation, and the intellectual courage to question even our most cherished assumptions about what works in human systems.

Through this commitment to evidence-based practice across all domains of quality management, we can build more robust, effective, and genuinely transformative approaches that honor both the complexity of technical systems and the richness of human experience while maintaining the intellectual honesty and systematic thinking that define excellence in our profession.