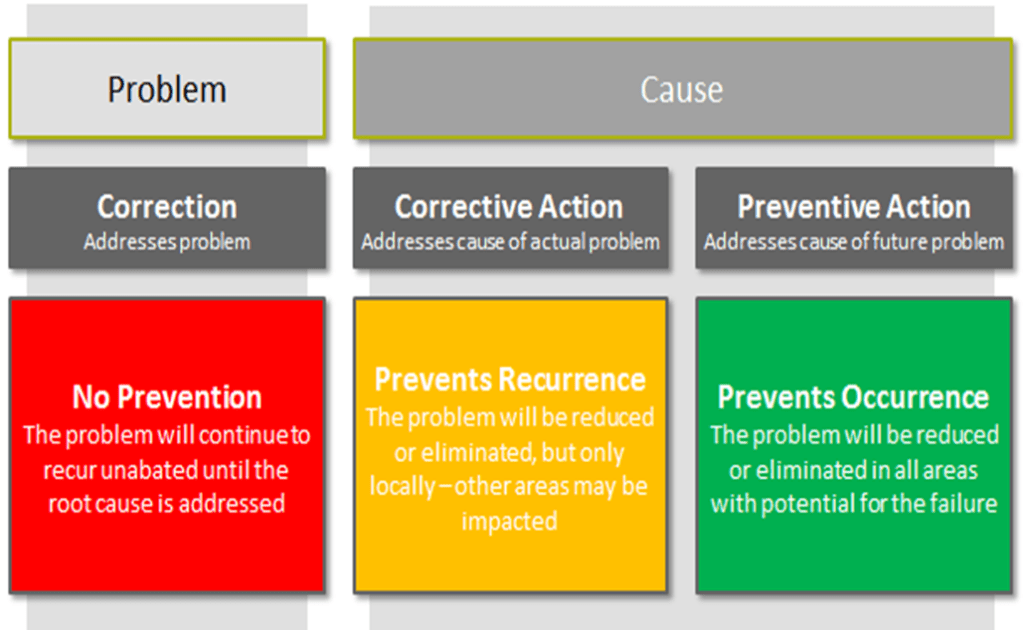

A causal factor is a significant contributor to an incident, event, or problem that, if eliminated or addressed, would have prevented the occurrence or reduced its severity or frequency. Here are the key points to understand about causal factors:

- Definition: A causal factor is a major unplanned, unintended contributor to an incident (a negative event or undesirable condition) that, if eliminated, would have either prevented the occurrence of the incident or reduced its severity or frequency.

- Distinction from root cause: While a causal factor contributes to an incident, it is not necessarily the primary driver. The root cause, on the other hand, is the fundamental reason for the occurrence of a problem or event. (Pay attention to the deficiencies of the model)

- Multiple contributors: An incident may have multiple causal factors, and eliminating one causal factor might not prevent the incident entirely but could reduce its likelihood or impact. Swiss-Cheese Model.

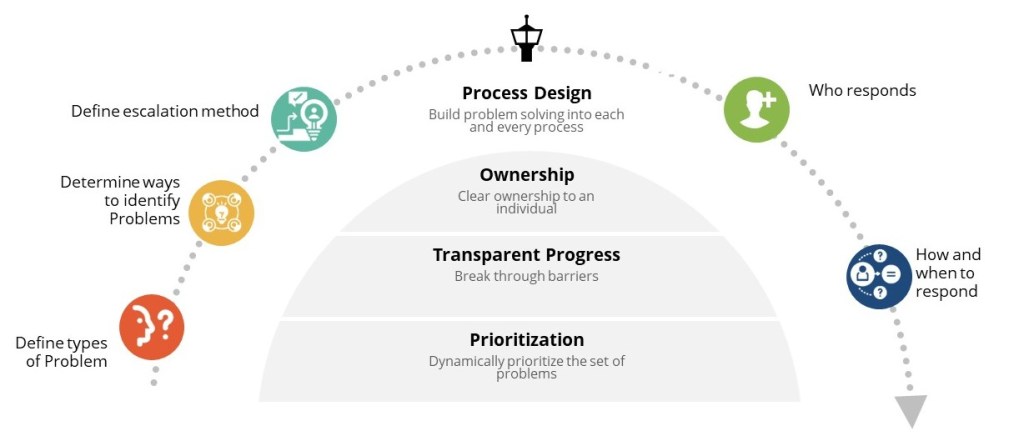

- Identification methods: Causal factors can be identified through various techniques, including: Root cause analysis (including such tools as fishbone diagrams (Ishikawa diagrams) or the Why-Why technique), Causal Learning Cycle(CLC) analysis, and Causal factor charting.

- Importance in problem-solving: Identifying causal factors is crucial for developing effective preventive measures and improving safety, quality, and efficiency.

- Characteristics: Causal factors must be mistakes, errors, or failures that directly lead to an incident or fail to mitigate its consequences. They should not contain other causal factors within them.

- Distinction from root causes: It’s important to note that root causes are not causal factors but rather lead to causal factors. Examples of root causes often mistaken for causal factors include inadequate procedures, improper training, or poor work culture.

Human Factors are not always Causal Factors, but can be!

Human factor and human error are related concepts but are not the same. A human error is always a causal factor, and the human factor explains why human errors can happen.

Human Error

Human error refers to an unintentional action or decision that fails to achieve the intended outcome. It encompasses mistakes, slips, lapses, and violations that can lead to accidents or incidents. There are two types:

- Unintentional Errors include slips (attentional failures) and lapses (memory failures) caused by distractions, interruptions, fatigue, or stress.

- Intentional Errors are violations in which an individual knowingly deviates from safe practices, procedures, or regulations. They are often categorized into routine, situational, or exceptional violations.

Human Factors

Human factors is a broader field that studies how humans interact with various system elements, including tools, machines, environments, and processes. It aims to optimize human well-being and overall system performance by understanding human capabilities, limitations, behaviors, and characteristics.

- Physical Ergonomics focuses on human anatomical, anthropometric, physiological, and biomechanical characteristics.

- Cognitive Ergonomics deals with mental processes such as perception, memory, reasoning, and motor response.

- Organizational Ergonomics involves optimizing organizational structures, policies, and processes to improve overall system performance and worker well-being.

Relationship Between Human Factors and Human Error

- Causal Relationship: Human factors delve into the underlying reasons why human errors occur. They consider the conditions and systems that contribute to errors, such as poor design, inadequate training, high workload, and environmental factors.

- Error Prevention: By addressing human factors, organizations can design systems and processes that minimize the likelihood of human errors. This includes implementing error-proofing solutions, improving ergonomics, and enhancing training and supervision.

Key Differences

- Focus:

- Human Error: Focuses on the outcome of an action or decision that fails to achieve the intended result.

- Human Factors: Focuses on the broader context and conditions that influence human performance and behavior.

- Approach:

- Human Error: Often addressed through training, disciplinary actions, and procedural changes.

- Human Factors: Involves a multidisciplinary approach to design systems, environments, and processes that support optimal human performance and reduce the risk of errors.