As we celebrate International Workers’ Day this May 1st, it is an opportune moment to reflect on the profound connection between workers’ rights and effective quality management. The pursuit of quality cannot be separated from how we treat, empower, and respect the rights of those who create that quality daily. Today’s post examines this critical relationship, drawing from the principles I’ve advocated throughout my blog, and challenges us to reimagine quality management as fundamentally worker-centered.

The Historical Connection Between Workers’ Rights and Quality

International Workers’ Day commemorates the historic struggles and gains made by workers and the labor movement. This celebration reminds us that the evolution of quality management has paralleled the fight for workers’ rights. Quality is inherently a progressive endeavor, fundamentally anti-Taylorist in nature. Frederick Taylor’s scientific management approach reduced workers to interchangeable parts in a machine, stripping them of autonomy and creativity – precisely the opposite of what modern quality management demands.

The quality movement, from Deming onwards, has recognized that treating workers as mere cogs undermines the very foundations of quality. When we champion human rights and center those whose rights are challenged, we’re not engaging in politics separate from quality – we’re acknowledging the fundamental truth that quality cannot exist without empowered, respected workers.

Driving Out Fear: The Essential Quality Right

“No one can put in his best performance unless he feels secure,” wrote Deming thirty-five years ago. Yet today, fear remains ubiquitous in corporate culture, undermining the very quality we seek to create. As quality professionals, we must confront this reality at every opportunity.

Fear in the workplace manifests in multiple ways, each destructive to quality:

| Source of Fear | Description | Impact on Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Competition | Managers often view anxiety generated by competition between co-workers as positive, encouraging competition for scarce resources, power, and status | Undermines collaboration necessary for system-wide quality improvements |

| “Us and Them” Culture | Silos proliferate, creating barriers between staff and supervisors | Prevents holistic quality approaches that span departmental boundaries |

| Blame Culture | Focus on finding fault rather than improving systems, often centered around the concept of “human error” | Discourages reporting of issues, driving quality problems underground |

When workers operate in fear, quality inevitably suffers. They hide mistakes rather than report them, avoid innovation for fear of failure, and focus on protecting themselves rather than improving systems. Driving out fear isn’t just humane – it’s essential for quality.

Key Worker Rights in Quality Management

Quality management systems that respect workers’ rights create environments where quality can flourish. Based on workplace investigation principles, these rights extend naturally to all quality processes.

The Right to Information

In any quality system, clarity is essential. Workers have the right to understand quality requirements, the rationale behind procedures, and how their work contributes to the overall quality system. Transparency sets the stage for collaboration, where everyone works toward a common quality goal with full understanding.

The Right to Confidentiality and Non-Retaliation

Workers must feel safe reporting quality issues without fear of punishment. This means protecting their confidentiality when appropriate and establishing clear non-retaliation policies. One of the pillars of workplace equity is ensuring that employees are shielded from retaliation when they raise concerns, reinforcing a commitment to a culture where individuals can voice quality issues without fear.

The Right to Participation and Representation

The Who-What Matrix is a powerful tool to ensure the right people are involved in quality processes. By including a wider set of people, this approach creates trust, commitment, and a sense of procedural justice-all essential for quality success. Workers deserve representation in decisions that affect their ability to produce quality work.

Worker Empowerment: The Foundation of Quality Culture

Empowerment is not just a nice-to-have; it’s a foundational element of any true quality culture. When workers are entrusted with authority to make decisions, initiate actions, and take responsibility for outcomes, both job satisfaction and quality improve. Unfortunately, empowerment rhetoric is sometimes misused within quality frameworks like TQM, Lean, and Six Sigma to justify increased work demands rather than genuinely empowering workers.

The concept of empowerment has its roots in social movements, including civil rights and women’s rights, where it described the process of gaining autonomy and self-determination for marginalized groups. In quality management, this translates to giving workers real authority to improve processes and address quality issues.

Mary Parker Follett’s Approach to Quality Through Autonomy

Follett emphasized giving workers autonomy to complete their jobs effectively, believing that when workers have freedom, they become happier, more productive, and more engaged. Her “power with” principle suggests that power should be shared broadly rather than concentrated, fostering a collaborative environment where quality can thrive.

Rejecting the Great Man Fallacy

Quality regulations often fall into the trap of the “Great Man Fallacy” – the misguided notion that one person through education, experience, and authority can ensure product safety, efficacy, and quality. This approach is fundamentally flawed.

People only perform successfully when they operate within well-built systems. Process drives success by leveraging the right people at the right time making the right decisions with the right information. No single person can ensure quality, and thinking otherwise sets up both individuals and systems for failure.

Instead, we need to build processes that leverage teams, democratize decisions, and drive reliable results. This approach aligns perfectly with respecting workers’ rights and empowering them as quality partners rather than subjects of quality control.

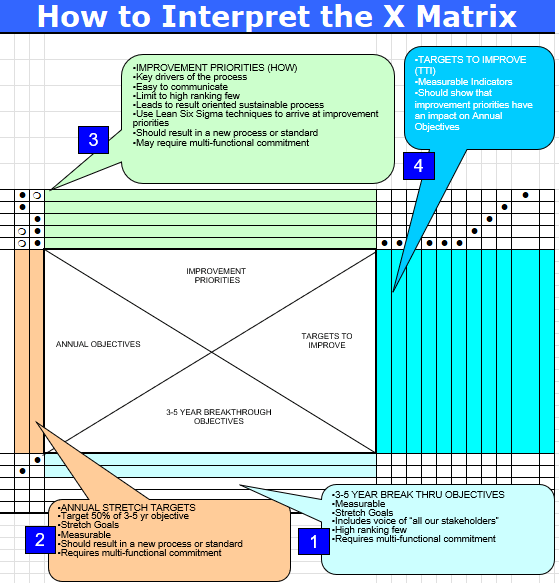

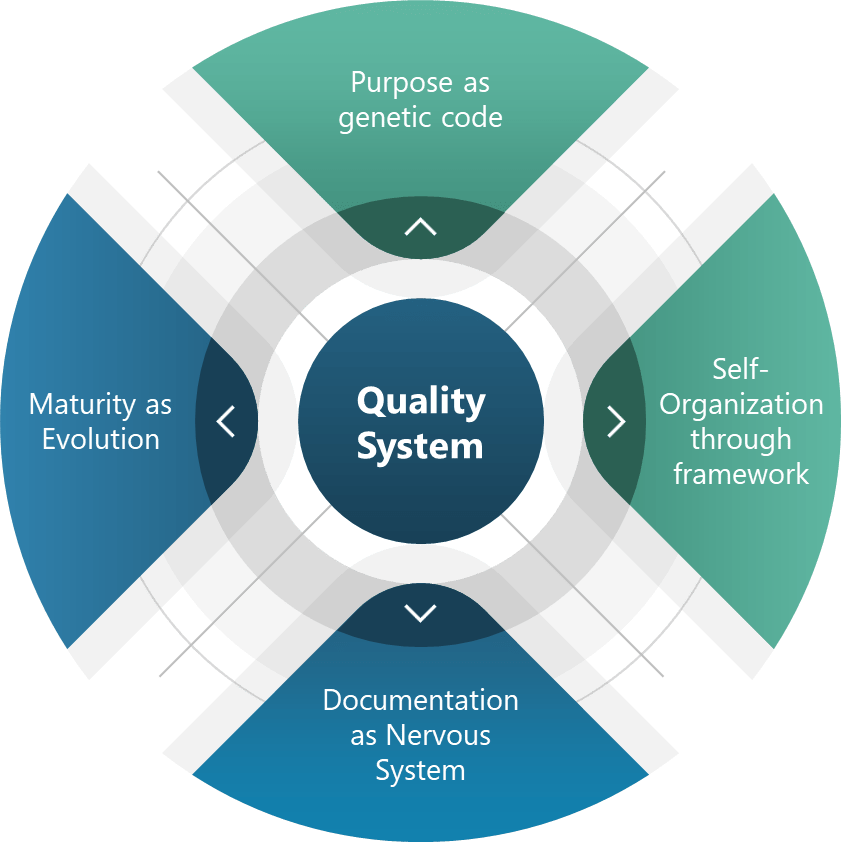

Quality Management as a Program: Centering Workers’ Rights

Quality needs to be managed as a program, walking a delicate line between long-term goals, short-term objectives, and day-to-day operations. As quality professionals, we must integrate workers’ rights into this program approach.

The challenges facing quality today-from hyperautomation to shifting customer expectations-can only be addressed through worker empowerment. Consider how these challenges demand a worker-centered approach:

| Challenge | Impact on Quality Management | Worker-Centered Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Analytics | Requires holistic data analysis and application | Develop talent strategies that upskill workers rather than replacing them |

| Hyper-Automation | Tasks previously done by humans being automated | Involve workers in automation decisions; focus on how automation can enhance rather than replace human work |

| Virtualization of Work | Rethinking how quality is executed in digital environments | Ensure workers have input on how virtual quality processes are designed |

| Shift to Resilient Operations | Need to adapt to changing risk levels in real-time | Enable employees to make faster decisions by building quality-informed judgment |

| Digitally Native Workforce | Changed expectations for how work is managed | Connect quality to values employees care about: autonomy, innovation, social issues |

To meet these challenges, we must shift from viewing quality as a function to quality as an interdisciplinary, participatory process. We need to break down silos and build autonomy, encouraging personal buy-in through participatory quality management.

May Day as a Reminder of Our Quality Mission

As International Workers’ Day approaches, I’m reminded that our quality mission is inseparable from our commitment to workers’ rights. This May Day, I encourage all quality professionals to:

- Evaluate how your quality systems either support or undermine workers’ rights

- Identify and eliminate sources of fear in your quality processes

- Create mechanisms for meaningful worker participation in quality decisions

- Reject hierarchical quality models in favor of democratic, empowering approaches

- Recognize that centering workers’ rights isn’t just ethical-it’s essential for quality

Quality management without respect for workers’ rights is not just morally questionable-it’s ineffective. The future of quality lies in approaches that are predictive, connected, flexible, and embedded. These can only be achieved when workers are treated as valued partners with protected rights and real authority.

This May Day, let’s renew our commitment to driving out fear, empowering workers, and building quality systems that respect the dignity and rights of every person who contributes to them. In doing so, we honor not just the historical struggles of workers, but also the true spirit of quality that puts people at its center.

What steps will you take this International Workers’ Day to strengthen the connection between workers’ rights and quality in your organization?