The Swiss Cheese Model, conceptualized by James Reason, fundamentally defined modern risk management by illustrating how layered defenses interact with active and latent failures to prevent or enable adverse events. This framework underpins the Four Layers of Protection, a systematic approach to mitigating risks across industries. By integrating Reason’s Theory of Active and Latent Failures with modern adaptations like resilience engineering, organizations can create robust, adaptive systems.

The Swiss Cheese Model and Reason’s Theory: A Foundation for Layered Defenses

Reason’s Theory distinguishes between active failures (immediate errors by frontline personnel) and latent failures (systemic weaknesses in design, management, or culture). The Swiss Cheese Model visualizes these failures as holes in successive layers of defense. When holes align, hazards penetrate the system. For example:

- In healthcare, a mislabeled specimen (active failure) might bypass defenses if staff are overworked (latent failure) and barcode scanners malfunction (technical failure).

- In aviation, a pilot’s fatigue-induced error (active) could combine with inadequate simulator training (latent) and faulty sensors (technical) to cause a near-miss.

This model emphasizes that no single layer is foolproof; redundancy and diversity across layers are critical.

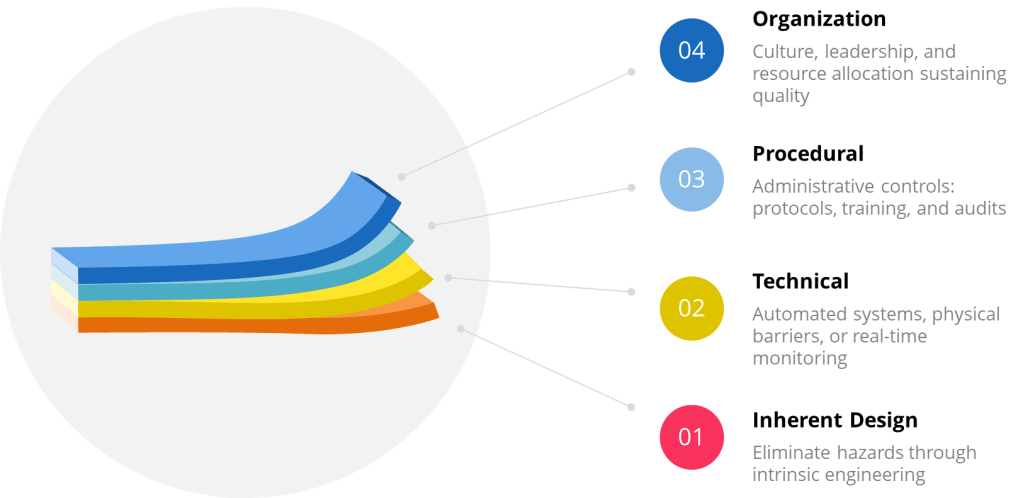

Four Layers of Protection:

While industries tailor layers to their risks, four core categories form the backbone of defense:

| Layer | Key Principles | Industry Example |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent Design | Eliminate hazards through intrinsic engineering (e.g., fail-safe mechanisms) | Pharmaceutical isolators preventing human contact with sterile products |

| Procedural | Administrative controls: protocols, training, and audits | ISO 27001’s access management policies for data security |

| Technical | Automated systems, physical barriers, or real-time monitoring | Safety Instrumented Systems (SIS) shutting down chemical reactors during leaks |

| Organizational | Culture, leadership, and resource allocation sustaining quality | Just Culture frameworks encouraging transparent incident reporting |

Industry Applications

1. Healthcare: Reducing Surgical Infections

- Inherent: Antimicrobial-coated implants resist biofilm formation.

- Procedural: WHO Surgical Safety Checklists standardize pre-operative verification.

- Technical: UV-C robots disinfect operating rooms post-surgery.

- Organizational: Hospital boards prioritizing infection prevention budgets.

2. Information Security: Aligning with ISO/IEC 27001

- Inherent: Encryption embedded in software design (ISO 27001 Annex A.10).

- Procedural: Regular penetration testing and access reviews (Annex A.12).

- Technical: Intrusion detection systems (Annex A.13).

- Organizational: Enterprise-wide risk assessments and governance (Annex A.5).

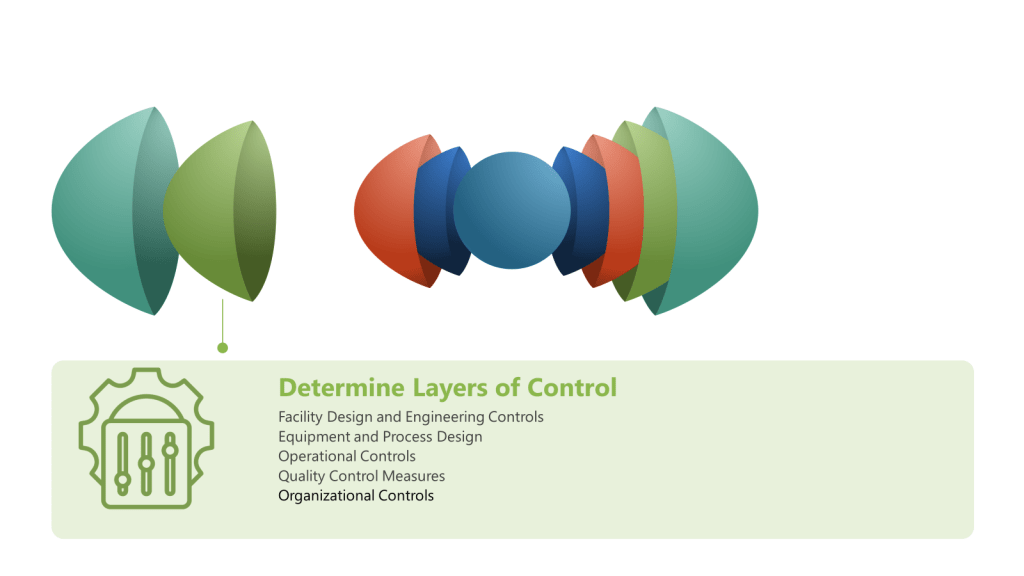

3. Biotech Manufacturing: Contamination Control

- Inherent: Closed-system bioreactors with sterile welders.

- Procedural: FDA-mandated Contamination Control Strategies (CCS).

- Technical: Real-time viable particle monitoring with auto-alerts.

- Organizational: Cross-functional teams analyzing trend data to preempt breaches.

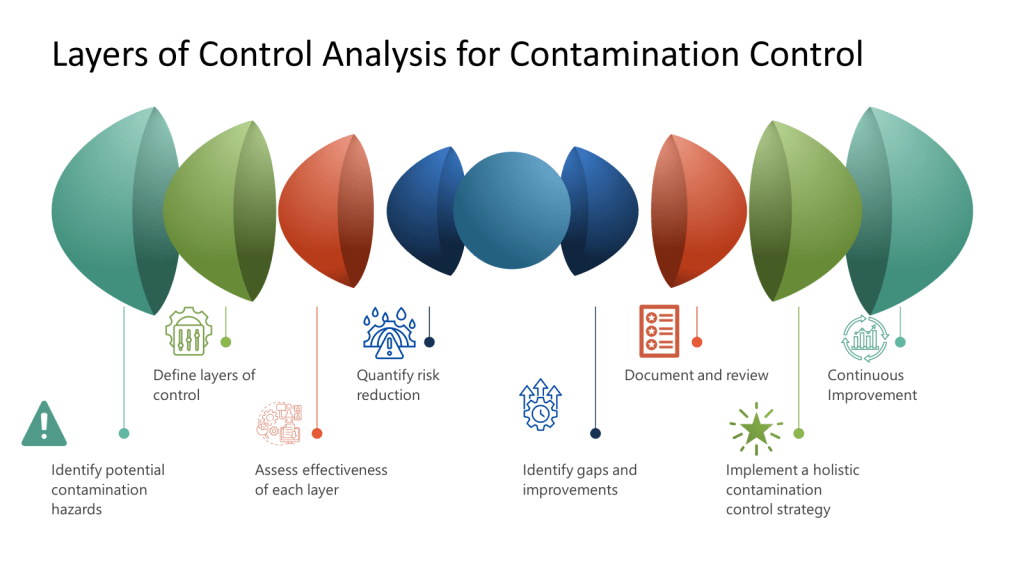

Contamination Control and Layers of Controls Analysis (LOCA)

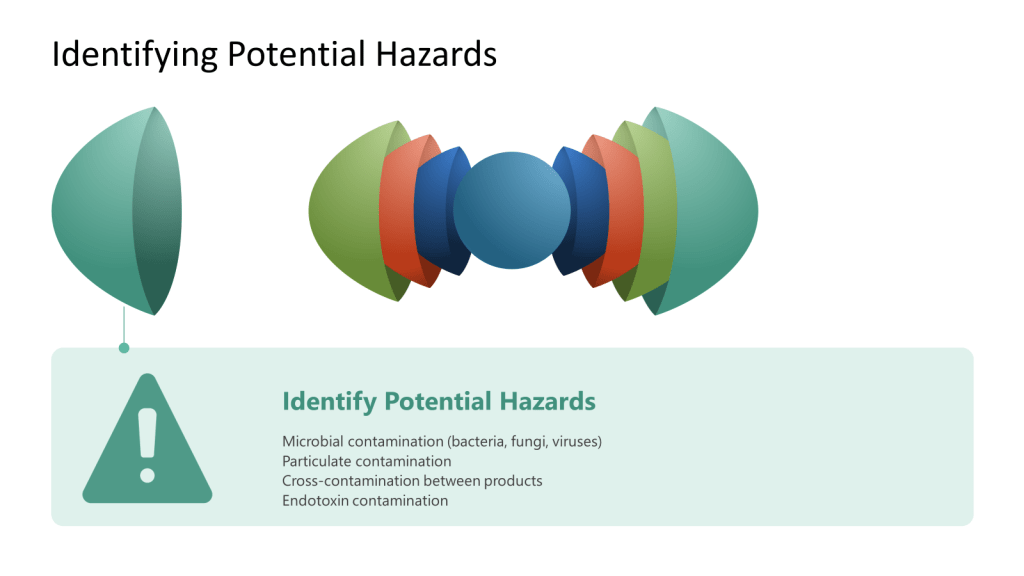

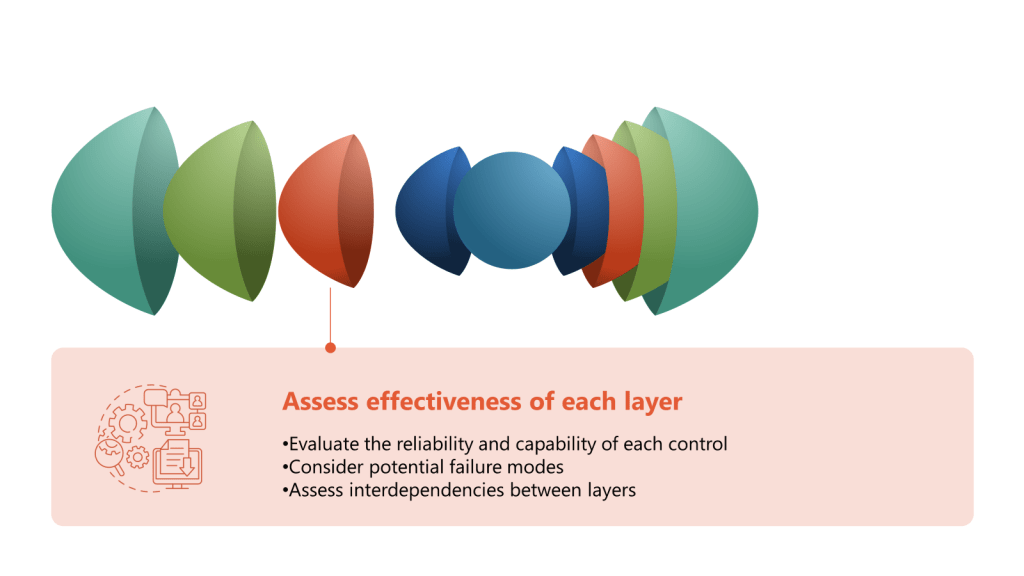

In contamination-critical industries, a Layers of Controls Analysis (LOCA) evaluates how failures in one layer impact others. For example:

- Procedural Failure: Skipping gowning steps in a cleanroom.

- Technical Compromise: HEPA filter leaks due to poor maintenance.

- Organizational Gap: Inadequate staff training on updated protocols.

LOCA reveals that latent organizational failures (e.g., insufficient training budgets) often undermine technical and procedural layers. LOCA ties contamination risks to systemic resource allocation, not just frontline errors.

Integration with ISO/IEC 27001

ISO/IEC 27001, the international standard for information security, exemplifies layered risk management:

| ISO 27001 Control (Annex A) | Corresponding Layer | Example |

|---|---|---|

| A.8.3 (Information labeling) | Procedural | Classifying data by sensitivity |

| A.9.4 (Network security) | Technical | Firewalls and VPNs |

| A.11.1 (Physical security) | Inherent/Technical | Biometric access to server rooms |

| A.5.1 (Policies for IS) | Organizational | Board-level oversight of cyber risks |

This alignment ensures that technical safeguards (e.g., encryption) are reinforced by procedural (e.g., audits) and organizational (e.g., governance) layers, mirroring the Swiss Cheese Model’s redundancy principle.

Resilience Engineering: Evolving the Layers

Resilience engineering moves beyond static defenses, focusing on a system’s capacity to anticipate, adapt, and recover from disruptions. It complements the Four Layers by adding dynamism:

| Traditional Layer | Resilience Engineering Approach | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent Design | Build adaptive capacity (e.g., modular systems) | Pharmaceutical plants with flexible cleanroom layouts |

| Procedural | Dynamic procedures adjusted via real-time data | AI-driven prescribing systems updating dosage limits during shortages |

| Technical | Self-diagnosing systems with graceful degradation | Power grids rerouting energy during cyberattacks |

| Organizational | Learning cultures prioritizing near-miss reporting | Aviation safety databases sharing incident trends globally |

Challenges and Future Directions

While the Swiss Cheese Model remains influential, critics argue it oversimplifies complex systems where layers interact unpredictably. For example, a malfunctioning algorithm (technical) could override procedural safeguards, necessitating organizational oversight of machine learning outputs.

Future applications will likely integrate:

- Predictive Analytics: Leverages advanced algorithms, machine learning, and vast datasets to forecast future risks and opportunities, transforming risk management from a reactive to a proactive discipline. By analyzing historical and real-time data, predictive analytics identifies patterns and anomalies that signal potential threats—such as equipment failures or contamination events —enabling organizations to anticipate and mitigate risks before they escalate. The technology’s adaptability allows it to integrate internal and external data sources, providing dynamic, data-driven insights that support better decision-making, resource allocation, and compliance monitoring. As a result, predictive analytics not only enhances operational resilience and efficiency but also reduces costs associated with failures, recalls, or regulatory breaches, making it an indispensable tool for modern risk and quality management.

- Human-Machine Teaming: Integrates human cognitive flexibility with machine precision to create collaborative systems that outperform isolated human or machine efforts. By framing machines as adaptive teammates rather than passive tools, HMT enables dynamic task allocation. Key benefits include accelerated decision-making through AI-driven data synthesis, reduced operational errors via automated safeguards, and enhanced resilience in complex environments. However, effective HMT requires addressing challenges such as establishing bidirectional trust through explainable AI, aligning ethical frameworks for accountability, and balancing autonomy levels through risk-categorized architectures. As HMT evolves, success hinges on designing systems that leverage human intuition and machine scalability while maintaining rigorous quality protocols.

- Epistemic Governance: The processes through which actors collectively shape perceptions, validate knowledge, and steer decision-making in complex systems, particularly during crises. Rooted in the dynamic interplay between recognized reality (actors’ constructed understanding of a situation) and epistemic work (efforts to verify, apply, or challenge knowledge), this approach emphasizes adaptability over rigid frameworks. By appealing to norms like transparency and scientific rigor, epistemic governance bridges structural frameworks (e.g., ISO standards) and grassroots actions, enabling systems to address latent organizational weaknesses while fostering trust. It also confronts power dynamics in knowledge production, ensuring marginalized voices inform policies—a critical factor in sustainability and crisis management where equitable participation shapes outcomes. Ultimately, it transforms governance into a reflexive practice, balancing institutional mandates with the agility to navigate evolving threats.

Conclusion

The Four Layers of Protection, rooted in Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model, provide a versatile framework for managing risks—from data breaches to pharmaceutical contamination. By integrating standards and embracing resilience engineering, organizations can transform static defenses into adaptive systems capable of navigating modern complexities. As industries face evolving threats, the synergy between layered defenses and dynamic resilience will define the next era of risk management.