For all I love the hard dimensions of quality (i.e. process, training, validation, management review, auditing, measurement of KPI) I also stress in my practice how the soft dimension of communication and employee participation, and teamwork are critical to bringing about a culture of excellence. Without a strong quality culture, people will not be ready to commit and involve themselves fully in building and supporting a robust quality management system. The goal is to align top management behavior and the emergent culture to be consistent over time with the quality system philosophy or people will become cynical. In short, organizational culture should be compatible with quality values.

Quality culture is justifiably the rage and it is not going anywhere. If you are not actively engaging with it you are losing one of your mechanisms for success.

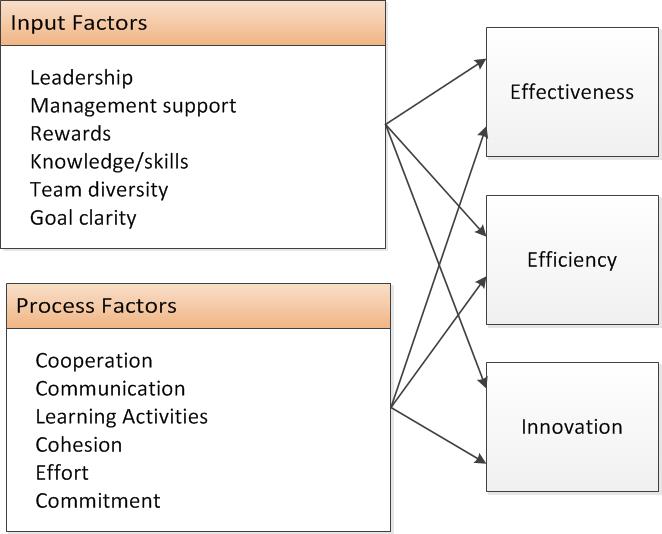

Quality Culture really serves as a way to categorize an organizational culture that intends to enhance quality permanently. There are two distinct elements characterizing this culture:

- A cultural/psychological element of shared values, beliefs, expectations, and commitment toward quality

- A structural/managerial element with defined processes that enhance quality and aim at coordinating individual efforts.

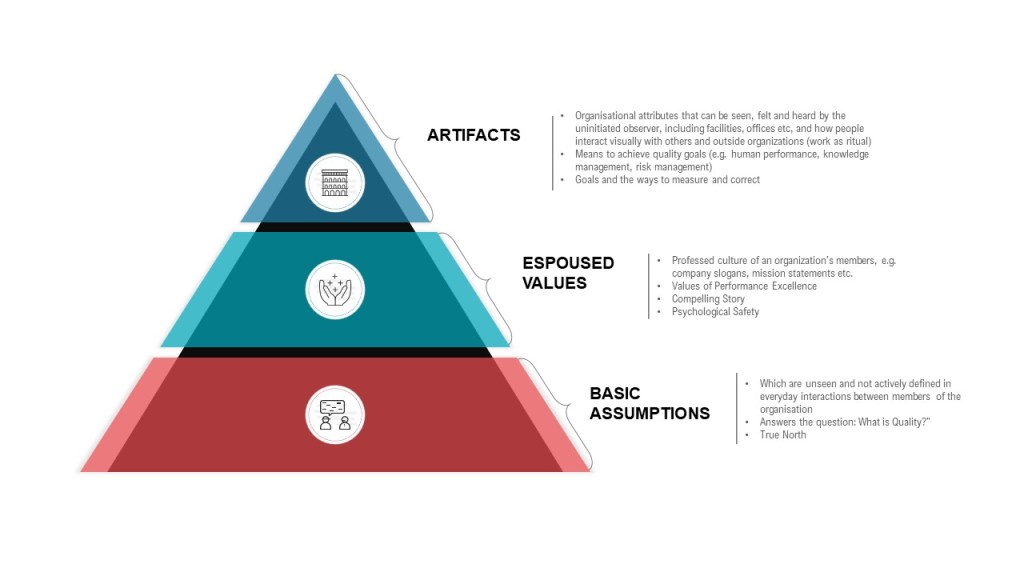

Schein’s model of organizational culture provides a valuable place to start in assessing quality culture:

- Visible quality artifacts (e.g. quality assessment tools)

- Espoused quality values (e.g. mission statement)

- Shared basic quality assumptions (e.g. quality commitment)

The first basic quality assumption to tackle is to answer what do you mean by Quality?

Even amongst quality professionals, we do not all seem to be in agreement on what we mean by Quality. Hence all the presentations at conferences and part of the focus on Quality 4.0 (the other part of the focus is mistaken worship of technology – go back to Deming people!)

Route out the ambiguity that results in:

- Uncontrollable fragmentation of quality thinking, discussion, and practices

- Superficiality of quality-related information and communication

- Conceptual confusion between the quality results and quality enablers, and between quality and many other related factors

- Disintegration of the foundation of quality

I like to place front and center the definition of quality from ISO 9000: “degree to which a set of inherent characteristics of an object fulfils requirements.” This definition emphasizes the relative nature of quality (“degree”) that also highlights the subjective perception of quality. The object of quality is defined more generally than for the goods or service products only. The object has its inherent characteristics that consist of all of its features or attributes. “Requirement” means here needs and expectations, which may be related to all interested parties of the object and the interaction. This definition of quality is also compatible the prevailing understanding of quality in everyday language.

For an organization, the definition of quality relates to the organization’s stakeholders. With the definition, we can consider both the quality of the organization as a whole and the quality of the entities being exchanged between the organization and its stakeholders. Products produced and delivered to the organization’s customers are especially significant entities in this context.

Following through with ISO9000’s definition of Quality management implying how the personal, organizational, or societal resources and activities or processes are managed with regard to quality, we are able to the framework for basic quality assumptions in an organization.

Herein usually lies your True North, a term used a lot, that recognizes that quality is a journey: there is no absolute destination point and we will never achieve perfection. Think of True North not as a destination, but as a term used to describe the ideal state of perfection that your organization should be continually striving for.

In espoused quality values we take the shared concept of quality and expand it to performance excellence as an integrated approach to the organizational performance management that results in:

- the delivery of ever-improving value to customers and stakeholders, contributing to organizational sustainability

- the improvement of overall organizational effectiveness and capabilities

- Organizational and personal learning.

We need to have a compelling story around these values.

A compelling story is a narrative that charts a change over time, showing how potential solutions fit into the espoused values. This story can generate more engagement from listeners than any burning platform ever will. By telling a compelling story, you clarify the motivation to develop discontent with the status quo. Let the story show the organization where you have come from and where you might go. The story must be consistent and adopted by all leaders in the organization. The leadership team should weave in the compelling story at all opportunities. They should ask their teams constantly, “What’s next?” “How can we make that even better?” “How did you improve your area today?”

Compelling stories often build on dissatisfaction by positioning against competitors. In the life science sector, it can be more effective to enshrine the patient in the center of the compelling story. People will support change when they see and experience a purposeful connection to an organization’s mission. The compelling story drives that.

Espoused values require strong and constant communication.

Espoused values have more levers for change than basic assumptions. While I placed True North down in assumptions, in all honestly it will for a central part of that compelling story and drive the adoption of the espoused values.

It is here we need to build and reaffirm psychological safety.

In the post “Driving towards a Culture of Excellence” I provided elements of a high-performing culture that count as artifacts of quality, stemming from the values.