Naïve realism—the unconscious belief that our perception of reality is objective and universally shared—acts as a silent saboteur in professional and personal decision-making. While this mindset fuels confidence, it also blinds us to alternative perspectives, amplifies cognitive biases, and undermines collaborative problem-solving. This blog post explores how this psychological trap distorts critical processes and offers actionable strategies to counteract its influence, drawing parallels to frameworks like the Pareto Principle and insights from risk management research.

Problem Solving: When Certainty Breeds Blind Spots

Naïve realism convinces us that our interpretation of a problem is the only logical one, leading to overconfidence in solutions that align with preexisting beliefs. For instance, teams often dismiss contradictory evidence in favor of data that confirms their assumptions. A startup scaling a flawed product because early adopters praised it—while ignoring churn data—exemplifies this trap. The Pareto Principle’s “vital few” heuristic can exacerbate this bias by oversimplifying complex issues. Organizations might prioritize frequent but low-impact problems, neglecting rare yet catastrophic risks, such as cybersecurity vulnerabilities masked by daily operational hiccups.

Functional fixedness, another byproduct of naïve realism, stifles innovation by assuming resources can only be used conventionally. To mitigate this pitfall, teams should actively challenge assumptions through adversarial brainstorming, asking questions like “Why will this solution fail?” Involving cross-functional teams or external consultants can also disrupt echo chambers, injecting fresh perspectives into problem-solving processes.

Risk Management: The Illusion of Objectivity

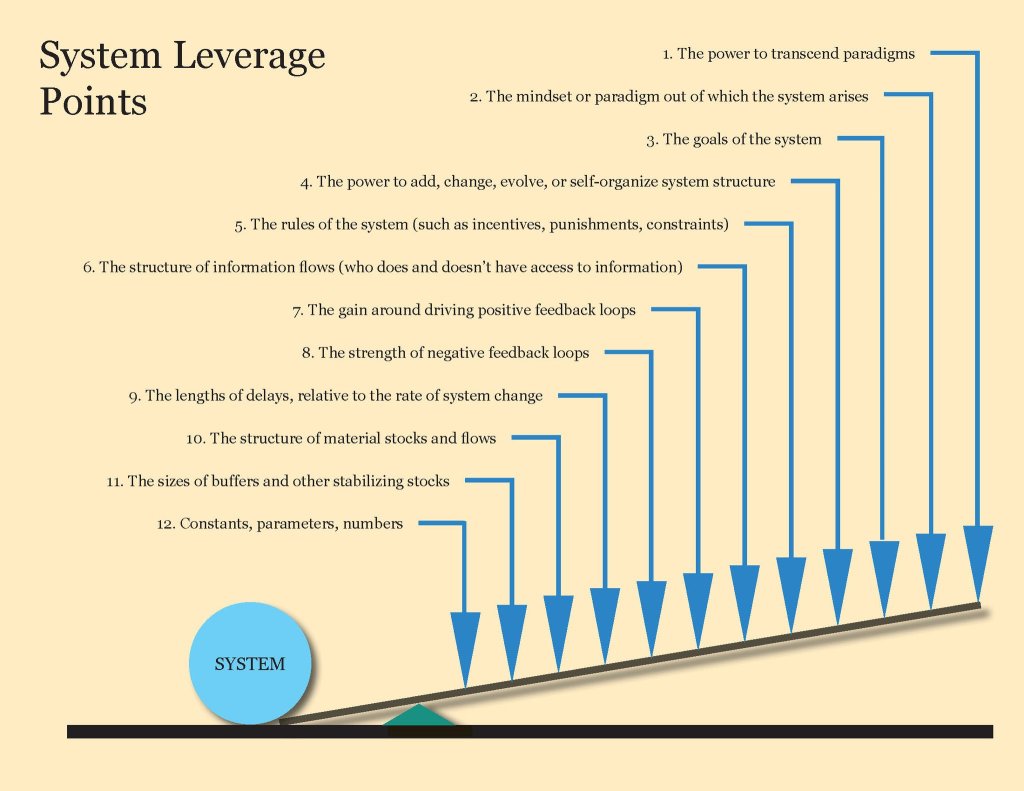

Risk assessments are inherently subjective, yet naïve realism convinces decision-makers that their evaluations are purely data-driven. Overreliance on historical data, such as prioritizing minor customer complaints over emerging threats, mirrors the Pareto Principle’s “static and historical bias” pitfall.

Reactive devaluation further complicates risk management. Organizations can counteract these biases by appropriately leveraging risk management to drive subjectivity out while better accounting for uncertainty. Simulating worst-case scenarios, such as sudden supplier price hikes or regulatory shifts, also surfaces blind spots that static models overlook.

Decision Making: The Myth of the Rational Actor

Even in data-driven cultures, subjectivity stealthily shapes choices. Leaders often overestimate alignment within teams, mistaking silence for agreement. Individuals frequently insist their assessments are objective despite clear evidence of self-enhancement bias. This false consensus erodes trust and stifles dissent with the assumption that future preferences will mirror current ones.

Organizations must normalize dissent through anonymous voting or “red team” exercises to dismantle these myths, including having designated critics scrutinize plans. Adopting probabilistic thinking, where outcomes are assigned likelihoods instead of binary predictions, reduces overconfidence.

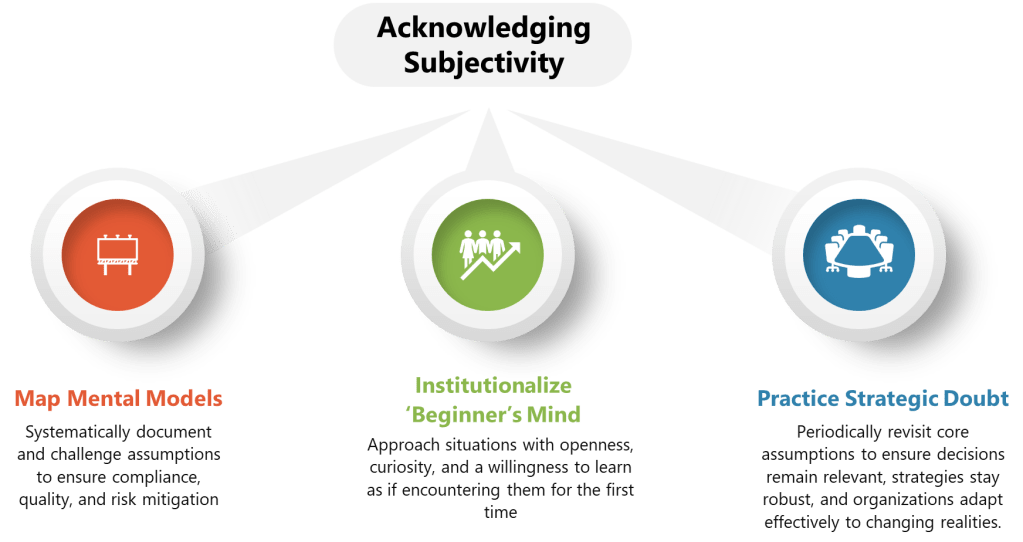

Acknowledging Subjectivity: Three Practical Steps

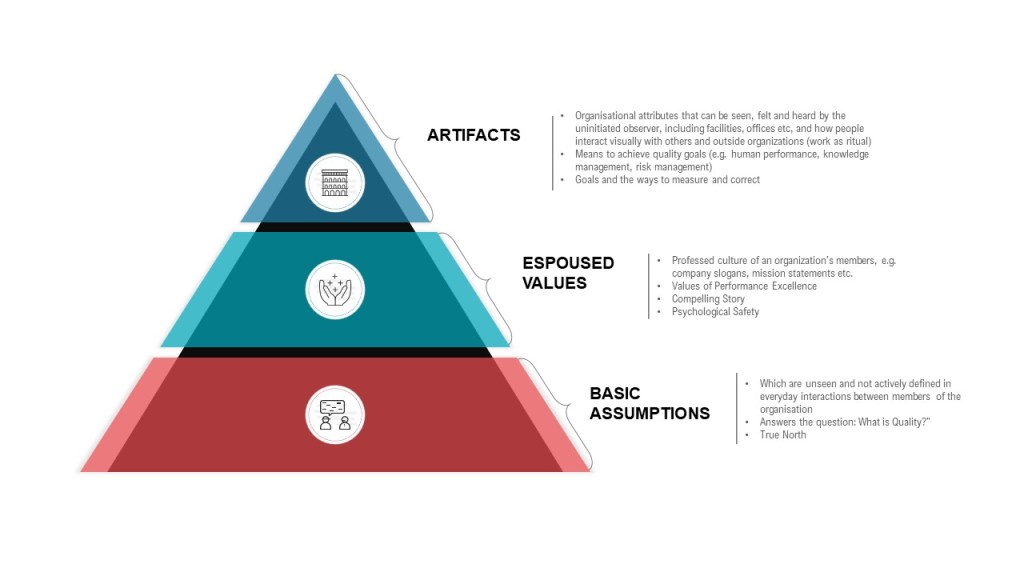

1. Map Mental Models

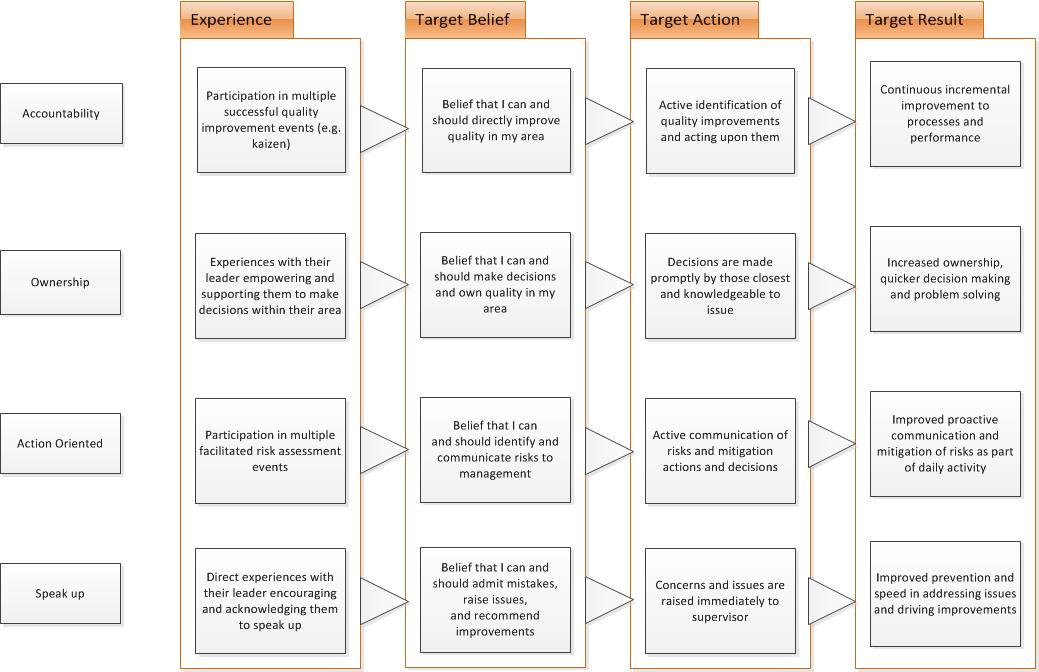

Mapping mental models involves systematically documenting and challenging assumptions to ensure compliance, quality, and risk mitigation. For example, during risk assessments or deviation investigations, teams should explicitly outline their assumptions about processes, equipment, and personnel. Statements such as “We assume the equipment calibration schedule is sufficient to prevent deviations” or “We assume operator training is adequate to avoid errors” can be identified and critically evaluated.

Foster a culture of continuous improvement and accountability by stress-testing assumptions against real-world data—such as audit findings, CAPA (Corrective and Preventive Actions) trends, or process performance metrics—to reveal gaps that might otherwise go unnoticed. For instance, a team might discover that while calibration schedules meet basic requirements, they fail to account for unexpected environmental variables that impact equipment accuracy.

By integrating assumption mapping into routine GMP activities like risk assessments, change control reviews, and deviation investigations, organizations can ensure their decision-making processes are robust and grounded in evidence rather than subjective beliefs. This practice enhances compliance and strengthens the foundation for proactive quality management.

2. Institutionalize ‘Beginner’s Mind’

A beginner’s mindset is about approaching situations with openness, curiosity, and a willingness to learn as if encountering them for the first time. This mindset challenges the assumptions and biases that often limit creativity and problem-solving. In team environments, fostering a beginner’s mindset can unlock fresh perspectives, drive innovation, and create a culture of continuous improvement. However, building this mindset in teams requires intentional strategies and ongoing reinforcement to ensure it is actively utilized.

What is a Beginner’s Mindset?

At its core, a beginner’s mindset involves setting aside preconceived notions and viewing problems or opportunities with fresh eyes. Unlike experts who may rely on established knowledge or routines, individuals with a beginner’s mindset embrace uncertainty and ask fundamental questions such as “Why do we do it this way?” or “What if we tried something completely different?” This perspective allows teams to challenge the status quo, uncover hidden opportunities, and explore innovative solutions that might be overlooked.

For example, adopting this mindset in the workplace might mean questioning long-standing processes that no longer serve their purpose or rethinking how resources are allocated to align with evolving goals. By removing the constraints of “we’ve always done it this way,” teams can approach challenges with curiosity and creativity.

How to Build a Beginner’s Mindset in Teams

Fostering a beginner’s mindset within teams requires deliberate actions from leadership to create an environment where curiosity thrives. Here are some key steps to build this mindset:

- Model Curiosity and Openness

Leaders play a critical role in setting the tone for their teams. By modeling curiosity—asking questions, admitting gaps in knowledge, and showing enthusiasm for learning—leaders demonstrate that it is safe and encouraged to approach work with an open mind. For instance, during meetings or problem-solving sessions, leaders can ask questions like “What haven’t we considered yet?” or “What would we do if we started from scratch?” This signals to team members that exploring new ideas is valued over rigid adherence to past practices. - Encourage Questioning Assumptions

Teams should be encouraged to question their assumptions regularly. Structured exercises such as “assumption audits” can help identify ingrained beliefs that may no longer hold true. By challenging assumptions, teams open themselves up to new insights and possibilities. - Create Psychological Safety

A beginner’s mindset flourishes in environments where team members feel safe taking risks and sharing ideas without fear of judgment or failure. Leaders can foster psychological safety by emphasizing that mistakes are learning opportunities rather than failures. For example, during project reviews, instead of focusing solely on what went wrong, leaders can ask, “What did we learn from this experience?” This shifts the focus from blame to growth and encourages experimentation. - Rotate Roles and Responsibilities

Rotating team members across roles or projects is an effective way to cultivate fresh perspectives. When individuals step into unfamiliar areas of responsibility, they are less likely to rely on habitual thinking and more likely to approach tasks with curiosity and openness. For instance, rotating quality assurance personnel into production oversight roles can reveal inefficiencies or risks that might have been overlooked due to overfamiliarity within silos. - Provide Opportunities for Learning

Continuous learning is essential for maintaining a beginner’s mindset. Organizations should invest in training programs, workshops, or cross-functional collaborations that expose teams to new ideas and approaches. For example, inviting external speakers or consultants to share insights from other industries can inspire innovative thinking within teams by introducing them to unfamiliar concepts or methodologies. - Use Structured Exercises for Fresh Thinking

Design Thinking exercises or brainstorming techniques like “reverse brainstorming” (where participants imagine how to create the worst possible outcome) can help teams break free from conventional thinking patterns. These activities force participants to look at problems from unconventional angles and generate novel solutions.

Ensuring Teams Utilize a Beginner’s Mindset

Building a beginner’s mindset is only half the battle; ensuring it is consistently applied requires ongoing reinforcement:

- Integrate into Processes: Embed beginner’s mindset practices into regular workflows such as project kickoffs, risk assessments, or strategy sessions. For example, make it standard practice to start meetings by revisiting assumptions or brainstorming alternative approaches before diving into execution plans.

- Reward Curiosity: Recognize and reward behaviors that reflect a beginner’s mindset—such as asking insightful questions, proposing innovative ideas, or experimenting with new approaches—even if they don’t immediately lead to success.

- Track Progress: Use metrics like the number of new ideas generated during brainstorming sessions or the diversity of perspectives incorporated into decision-making processes to measure how well teams utilize a beginner’s mindset.

- Reflect Regularly: Encourage teams to reflect on using the beginner’s mindset through retrospectives or debriefs after significant projects and events. Questions like “How did our openness to new ideas impact our results?” or “What could we do differently next time?” help reinforce the importance of maintaining this perspective.

Organizations can ensure their teams consistently leverage the power of a beginner’s mindset by cultivating curiosity, creating psychological safety, and embedding practices that challenge conventional thinking into daily operations. This drives innovation and fosters adaptability and resilience in an ever-changing business landscape.

3. Revisit Assumptions by Practicing Strategic Doubt

Assumptions are the foundation of decision-making, strategy development, and problem-solving. They represent beliefs or premises we take for granted, often without explicit evidence. While assumptions are necessary to move forward in uncertain environments, they are not static. Over time, new information, shifting circumstances, or emerging trends can render them outdated or inaccurate. Periodically revisiting core assumptions is essential to ensure decisions remain relevant, strategies stay robust, and organizations adapt effectively to changing realities.

Why Revisiting Assumptions Matters

Assumptions often shape the trajectory of decisions and strategies. When left unchecked, they can lead to flawed projections, misallocated resources, and missed opportunities. For example, Kodak’s assumption that film photography would dominate forever led to its downfall in the face of digital innovation. Similarly, many organizations assume their customers’ preferences or market conditions will remain stable, only to find themselves blindsided by disruptive changes. Revisiting assumptions allows teams to challenge these foundational beliefs and recalibrate their approach based on current realities.

Moreover, assumptions are frequently made with incomplete knowledge or limited data. As new evidence emerges, whether through research, technological advancements, or operational feedback, testing these assumptions against reality is critical. This process ensures that decisions are informed by the best available information rather than outdated or erroneous beliefs.

How to Periodically Revisit Core Assumptions

Revisiting assumptions requires a structured approach integrating critical thinking, data analysis, and collaborative reflection.

1. Document Assumptions from the Start

The first step is identifying and articulating assumptions explicitly during the planning stages of any project or strategy. For instance, a team launching a new product might document assumptions about market size, customer preferences, competitive dynamics, and regulatory conditions. By making these assumptions visible and tangible, teams create a baseline for future evaluation.

2. Establish Regular Review Cycles

Revisiting assumptions should be institutionalized as part of organizational processes rather than a one-off exercise. Build assumption audits into the quality management process. During these sessions, teams critically evaluate whether their assumptions still hold true in light of recent data or developments. This ensures that decision-making remains agile and responsive to change.

3. Use Feedback Loops

Feedback loops provide real-world insights into whether assumptions align with reality. Organizations can integrate mechanisms such as surveys, operational metrics, and trend analyses into their workflows to continuously test assumptions.

4. Test Assumptions Systematically

Not all assumptions carry equal weight; some are more critical than others. Teams can prioritize testing based on three parameters: severity (impact if the assumption is wrong), probability (likelihood of being inaccurate), and cost of resolution (resources required to validate or adjust).

5. Encourage Collaborative Reflection

Revisiting assumptions is most effective when diverse perspectives are involved. Bringing together cross-functional teams—including leaders, subject matter experts, and customer-facing roles—ensures that blind spots are uncovered and alternative viewpoints are considered. Collaborative workshops or strategy recalibration sessions can facilitate this process by encouraging open dialogue about what has changed since the last review.

6. Challenge Assumptions with Data

Assumptions should always be validated against evidence rather than intuition alone. Teams can leverage predictive analytics tools to assess whether their assumptions align with emerging trends or patterns.

How Organizations Can Ensure Assumptions Are Utilized Effectively

To ensure revisited assumptions translate into actionable insights, organizations must integrate them into decision-making processes:

Monitor Continuously: Establish systems for continuously monitoring critical assumptions through dashboards or regular reporting mechanisms. This allows leadership to identify invalidated assumptions promptly and course-correct before significant risks materialize.

Update Strategies and Goals: Adjust goals and objectives based on revised assumptions to maintain alignment with current realities.

Refine KPIs: Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) should evolve alongside updated assumptions to reflect shifting priorities and external conditions. Metrics that once seemed relevant may need adjustment as new data emerges.

Embed Assumption Testing into Culture: Encourage teams to view assumption testing as an ongoing practice rather than a reactive measure. Leaders can model this behavior by openly questioning their own decisions and inviting critique from others.

From Certainty to Curious Inquiry

Naïve realism isn’t a personal failing but a universal cognitive shortcut. By recognizing its influence—whether in misapplying the Pareto Principle or dismissing dissent—we can reframe conflicts as opportunities for discovery. The goal isn’t to eliminate subjectivity but to harness it, transforming blind spots into lenses for sharper, more inclusive decision-making.

The path to clarity lies not in rigid certainty but in relentless curiosity.