ICH Q9(r1) can be reviewed as a revision that addresses long-standing issues of subjectivity in risk management. Subjectivity is a widespread problem throughout the quality sphere, posing significant challenges because it introduces personal biases, emotions, and opinions into decision-making processes that should ideally be driven by objective data and facts.

- Inconsistent Decision-Making: Subjective decision-making can lead to inconsistencies because different individuals may have varying opinions and biases. This inconsistency can result in unpredictable outcomes and make it challenging to establish standardized processes. For example, one manager might prioritize customer satisfaction based on personal experiences, while another might focus on cost-cutting, leading to conflicting strategies within the same organization.

- Bias and Emotional Influence: Subjectivity often involves emotional influence, which can cloud judgment and lead to decisions not in the organization’s best interest. For instance, a business owner might make decisions based on a personal attachment to a product or service rather than its market performance or profitability. This emotional bias can prevent the business from making necessary changes or investments, ultimately harming its growth and sustainability.

- Risk Management Issues: In risk assessments, subjectivity can significantly impact the identification and evaluation of risks. Subjective assessments may overlook critical risks or overemphasize less significant ones, leading to inadequate risk management strategies. Objective, data-driven risk assessments are essential to accurately identify and mitigate potential threats to the business. See ICHQ9(r1).

- Difficulty in Measuring Performance: Subjective criteria are often more complicated to quantify and measure, making it challenging to track performance and progress accurately. Objective metrics, such as key performance indicators (KPIs), provide clear, measurable data that can be used to assess the effectiveness of business processes and make informed decisions.

- Potential for Misalignment: Subjective decision-making can lead to misalignment between business goals and outcomes. For example, if subjective opinions drive project management decisions, the project may deviate from its original scope, timeline, or budget, resulting in unmet objectives and dissatisfied stakeholders.

- Impact on Team Dynamics: Subjectivity can also affect team dynamics and morale. Decisions perceived as biased or unfair can lead to dissatisfaction and conflict among team members. Objective decision-making, based on transparent criteria and data, helps build trust and ensures that all team members are aligned with the business’s goals.

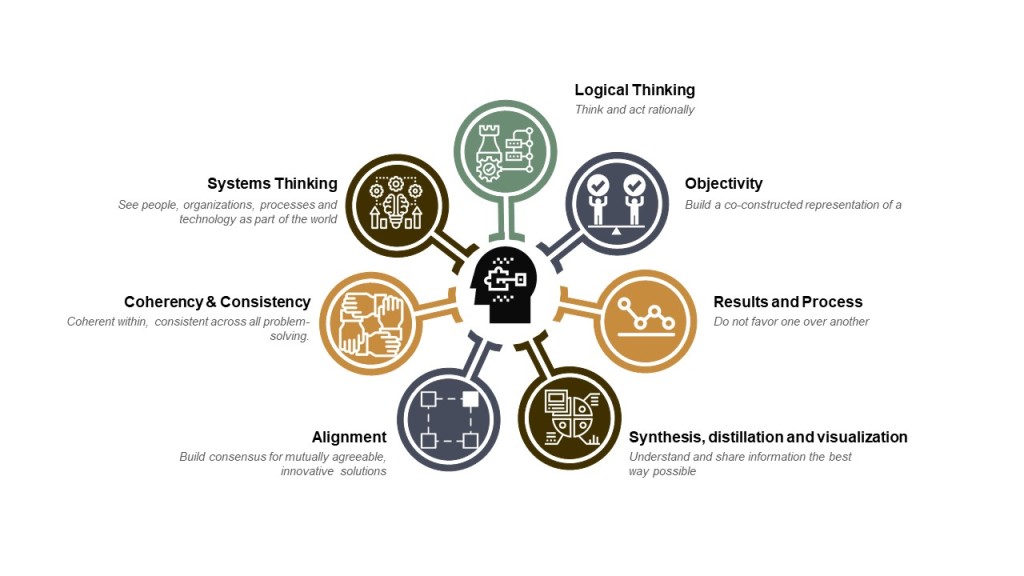

Every organization I’ve been in has a huge problem with subjectivity, and I’m confident in asserting none of us are doing enough to deal with the lack of objectivity, and we mostly rely on our intuition instead of on objective guidelines that will create unambiguous, holistic, and

universally usable models.

Understand the Decisions We Make

Every day, we make many decisions, sometimes without even noticing it. These decisions fall into four categories:

- Acceptances: It is a binary choice between accepting or rejecting;

- Choices: Opting for a subset from a group of alternatives;

- Constructions: Creating an ideal solution given accessible resources;

- Evaluations: Here, commitments back up the statements of worth to act

These decisions can be simple or complex, with manifold criteria and several perspectives. Decision-making is the process of choosing an option among manifold alternatives.

The Fallacy of Expert Immunity is a Major Source of Subjectivity

There is a widely incorrect belief that experts are impartial and immune to biases. However, the truth is that no one is immune to bias, not even experts. In many ways, experts are more susceptible to certain biases. The very making of expertise creates and underpins many of the biases. For example, experience and training make experts engage in more selective attention, use chunking and schemas (typical activities and their sequence), and rely on heuristics and expectations arising from past base rate experiences, utilizing a whole range of top-down cognitive processes that create a priori assumptions and expectations.

These cognitive processes often enable experts to make quick and accurate decisions. However, these mechanisms also create bias that can lead them in the wrong direction. Regardless of the utilities (and vulnerability) of such cognitive processing in experts, they do not make experts immune from bias, and indeed, expertise and experience may actually increase (or even cause) certain biases. Experts across domains are subject to cognitive vulnerabilities.

Even when experts are made aware of and acknowledge their biases, they nevertheless think they can overcome them by mere willpower. This is the illusion of control. Combating and countering these biases requires taking specific steps—willpower alone is inadequate to deal with the various manifestations of bias.

In fact, trying to deal with bias through the illusion of control may actually increase the bias due to “ironic processing” or “ironic rebound.” Hence, trying to minimize bias by willpower makes you think of it more and increases its effect. This is similar to a judge instructing jurors to disregard specific evidence. By doing so, the judge makes the jurors notice this evidence even more.

Such fallacies’ beliefs prevent dealing with biases because they dismiss their powers and existence. We need to acknowledge the impact of biases and understand their sources to take appropriate measures when needed and when possible to combat their effects.

| Fallacy | Incorrect Belief |

| Ethical Issues | It only happens to corrupt and unscrupulous individuals, an issue of morals and personal integrity, a question of personal character. |

| Bad Apples | It only happens to corrupt and unscrupulous individuals. It is an issue of morals and personal integrity, a question of personal character. |

| Expert Immunity | Experts are impartial and are not affected because bias does not impact competent experts doing their job with integrity. |

| Technological Protection | Using technology, instrumentation, automation, or artificial intelligence guarantees protection from human biases. |

| Blind Spot | Other experts are affected by bias, but not me. I am not biased; it is the other experts who are biased. |

| Illusion of Control | I am aware that bias impacts me, and therefore, I can control and counter its affect. I can overcome bias by mere willpower. |

Mitigating Subjectivity

There are four basic strategies to mitigate the impact of subjectivity.

Data-Driven Decision Making

Utilize data and analytics to inform decisions, reducing reliance on personal opinions and biases.

- Establish clear metrics with key performance indicators (KPI), key behavior indicators (KBI), and key risk indicators (KRI) that are aligned with objectives.

- Implement robust data collection and analysis systems to gather relevant, high-quality data.

- Use data visualization tools to present information in an easily digestible format.

- Train employees on data literacy and interpretation to ensure proper use of data insights.

- Regularly review and update data sources to maintain relevance and accuracy.

Standardized Processes

Implement standardized processes and procedures to ensure consistency and fairness in decision-making.

- Document and formalize decision-making procedures across the organization.

- Create standardized templates, checklists, and rubrics for evaluating options and making decisions.

- Implement a consistent review and approval process for major decisions.

- Regularly audit and update standardized processes to ensure they remain effective and relevant.

Education, Training, and Awareness

Educate and train employees and managers on the importance of objective decision-making and recognizing and minimizing personal biases.

- Conduct regular training sessions on cognitive biases and their impact on decision-making.

- Provide resources and tools to help employees recognize and mitigate their own biases.

- Encourage a culture of open discussion and constructive challenge to promote diverse perspectives.

- Implement mentoring programs to share knowledge and best practices for objective decision-making.

Digital Tools

Leverage digital tools and software to automate and streamline processes, reducing the potential for subjective influence. The last two is still more aspiration than reality.

- Implement workflow management tools to ensure consistent application of standardized processes.

- Use collaboration platforms to facilitate transparent and inclusive decision-making processes.

- Adopt decision support systems that use algorithms and machine learning to provide recommendations based on data analysis.

- Leverage artificial intelligence and predictive analytics to identify patterns and trends that may not be apparent to human decision-makers.