The concept of emergence—where complex behaviors arise unpredictably from interactions among simpler components—has haunted and inspired quality professionals since Aristotle first observed that “the whole is something besides the parts.” In modern quality systems, this ancient paradox takes new form: our meticulously engineered controls often birth unintended consequences, from phantom batch failures to self-reinforcing compliance gaps. Understanding emergence isn’t just an academic exercise—it’s a survival skill in an era where hyperconnected processes and globalized supply chains amplify systemic unpredictability.

The Spectrum of Emergence: From Predictable to Baffling

Emergence manifests across a continuum of complexity, each type demanding distinct management approaches:

1. Simple Emergence

Predictable patterns emerge from component interactions, observable even in abstracted models. Consider document control workflows: while individual steps like review or approval seem straightforward, their sequencing creates emergent properties like approval cycle times. These can be precisely modeled using flowcharts or digital twins, allowing proactive optimization.

2. Weak Emergence

Behaviors become explainable only after they occur, requiring detailed post-hoc analysis. A pharmaceutical company’s CAPA system might show seasonal trends in effectiveness—a pattern invisible in individual case reviews but emerging from interactions between manufacturing schedules, audit cycles, and supplier quality fluctuations. Weak emergence often reveals itself through advanced analytics like machine learning clustering.

3. Multiple Emergence

Here, system behaviors directly contradict component properties. A validated sterile filling line passing all IQ/OQ/PQ protocols might still produce unpredictable media fill failures when integrated with warehouse scheduling software. This “emergent invalidation” stems from hidden interaction vectors that only manifest at full operational scale.

4. Strong Emergence

Consistent with components but unpredictably manifested, strong emergence plagues culture-driven quality systems. A manufacturer might implement identical training programs across global sites, yet some facilities develop proactive quality innovation while others foster blame-avoidance rituals. The difference emerges from subtle interactions between local leadership styles and corporate KPIs.

5. Spooky Emergence

The most perplexing category, where system behaviors defy both component properties and simulation. A medical device company once faced identical cleanrooms producing statistically divergent particulate counts—despite matching designs, procedures, and personnel. Root cause analysis eventually traced the emergence to nanometer-level differences in HVAC duct machining, interacting with shift-change lighting schedules to alter airflow dynamics.

| Type | Characteristics | Quality System Example |

| Simple | Predictable through component analysis | Document control workflows |

| Weak | Explainable post-occurrence through detailed modeling | CAPA effectiveness trends |

| Multiple | Contradicts component properties, defies simulation | Validated processes failing at scale |

| Strong | Consistent with components but unpredictably manifested | Culture-driven quality behaviors |

| Spooky | Defies component properties and simulation entirely | Phantom batch failures in identical systems |

The Modern Catalysts of Emergence

Three forces amplify emergence in contemporary quality systems:

Hyperconnected Processes

IoT-enabled manufacturing equipment generates real-time data avalanches. A biologics plant’s environmental monitoring system might integrate 5,000 sensors updating every 15 seconds. The emergent property? A “data tide” that overwhelms traditional statistical process control, requiring AI-driven anomaly detection to discern meaningful signals.

Compressed Innovation Cycles

Compressed innovation cycles are transforming the landscape of product development and quality management. In this new paradigm, the pressure to deliver products faster—whether due to market demands, technological advances, or public health emergencies—means that the traditional, sequential approach to development is replaced by a model where multiple phases run in parallel. Design, manufacturing, and validation activities that once followed a linear path now overlap, requiring organizations to verify quality in real time rather than relying on staged reviews and lengthy data collection.

One of the most significant consequences of this acceleration is the telescoping of validation windows. Where stability studies and shelf-life determinations once spanned years, they are now compressed into a matter of months or even weeks. This forces quality teams to make critical decisions based on limited data, often relying on predictive modeling and statistical extrapolation to fill in the gaps. The result is what some call “validation debt”—a situation where the pace of development outstrips the accumulation of empirical evidence, leaving organizations to manage risks that may not be fully understood until after product launch.

Regulatory frameworks are also evolving in response to compressed innovation cycles. Instead of the traditional, comprehensive submission and review process, regulators are increasingly open to iterative, rolling reviews and provisional specifications that can be adjusted as more data becomes available post-launch. This shift places greater emphasis on computational evidence, such as in silico modeling and digital twins, rather than solely on physical testing and historical precedent.

The acceleration of development timelines amplifies the risk of emergent behaviors within quality systems. Temporal compression means that components and subsystems are often scaled up and integrated before they have been fully characterized or validated in isolation. This can lead to unforeseen interactions and incompatibilities that only become apparent at the system level, sometimes after the product has reached the market. The sheer volume and velocity of data generated in these environments can overwhelm traditional quality monitoring tools, making it difficult to identify and respond to critical quality attributes in a timely manner.

Another challenge arises from the collision of different quality management protocols. As organizations attempt to blend frameworks such as GMP, Agile, and Lean to keep pace with rapid development, inconsistencies and gaps can emerge. Cross-functional teams may interpret standards differently, leading to confusion or conflicting priorities that undermine the integrity of the quality system.

The systemic consequences of compressed innovation cycles are profound. Cryptic interaction pathways can develop, where components that performed flawlessly in isolation begin to interact in unexpected ways at scale. Validation artifacts—such as artificial stability observed in accelerated testing—may fail to predict real-world performance, especially when environmental variables or logistics introduce new stressors. Regulatory uncertainty increases as control strategies become obsolete before they are fully implemented, and critical process parameters may shift unpredictably during technology transfer or scale-up.

To navigate these challenges, organizations are adopting adaptive quality strategies. Predictive quality modeling, using digital twins and machine learning, allows teams to simulate thousands of potential interaction scenarios and forecast failure modes even with incomplete data. Living control systems, powered by AI and continuous process verification, enable dynamic adjustment of specifications and risk priorities as new information emerges. Regulatory agencies are also experimenting with co-evolutionary approaches, such as shared industry databases for risk intelligence and regulatory sandboxes for testing novel quality controls.

Ultimately, compressed innovation cycles demand a fundamental rethinking of quality management. The focus shifts from simply ensuring compliance to actively navigating complexity and anticipating emergent risks. Success in this environment depends on building quality systems that are not only robust and compliant, but also agile and responsive—capable of detecting, understanding, and adapting to surprises as they arise in real time.

Supply Chain Entanglement

Globalization has fundamentally transformed supply chains, creating vast networks that span continents and industries. While this interconnectedness has brought about unprecedented efficiencies and access to resources, it has also introduced a web of hidden interaction vectors—complex, often opaque relationships and dependencies that can amplify both risk and opportunity in ways that are difficult to predict or control.

At the heart of this complexity is the fragmentation of production across multiple jurisdictions. This spatial and organizational dispersion means that disruptions—whether from geopolitical tensions, natural disasters, regulatory changes, or even cyberattacks—can propagate through the network in unexpected ways, sometimes surfacing as quality issues, delays, or compliance failures far from the original source of the problem.

Moreover, the rise of powerful transnational suppliers, sometimes referred to as “Big Suppliers,” has shifted the balance of power within global value chains. These entities do not merely manufacture goods; they orchestrate entire ecosystems of production, labor, and logistics across borders. Their decisions about sourcing, labor practices, and compliance can have ripple effects throughout the supply chain, influencing not just operational outcomes but also the diffusion of norms and standards. This reconsolidation at the supplier level complicates the traditional view that multinational brands are the primary drivers of supply chain governance, revealing instead a more distributed and dynamic landscape of influence.

The hidden interaction vectors created by globalization are further obscured by limited supply chain visibility. Many organizations have a clear understanding of their direct, or Tier 1, suppliers but lack insight into the lower tiers where critical risks often reside. This opacity can mask vulnerabilities such as overreliance on a single region, exposure to forced labor, or susceptibility to regulatory changes in distant markets. As a result, companies may find themselves blindsided by disruptions that originate deep within their supply networks, only becoming apparent when they manifest as operational or reputational crises.

In this environment, traditional risk management approaches are often insufficient. The sheer scale and complexity of global supply chains demand new strategies for mapping connections, monitoring dependencies, and anticipating how shocks in one part of the world might cascade through the system. Advanced analytics, digital tools, and collaborative relationships with suppliers are increasingly essential for uncovering and managing these hidden vectors. Ultimately, globalization has made supply chains more efficient but also more fragile, with hidden interaction points that require constant vigilance and adaptive management to ensure resilience and sustained performance.

Emergence and the Success/Failure Space: Navigating Complexity in System Design

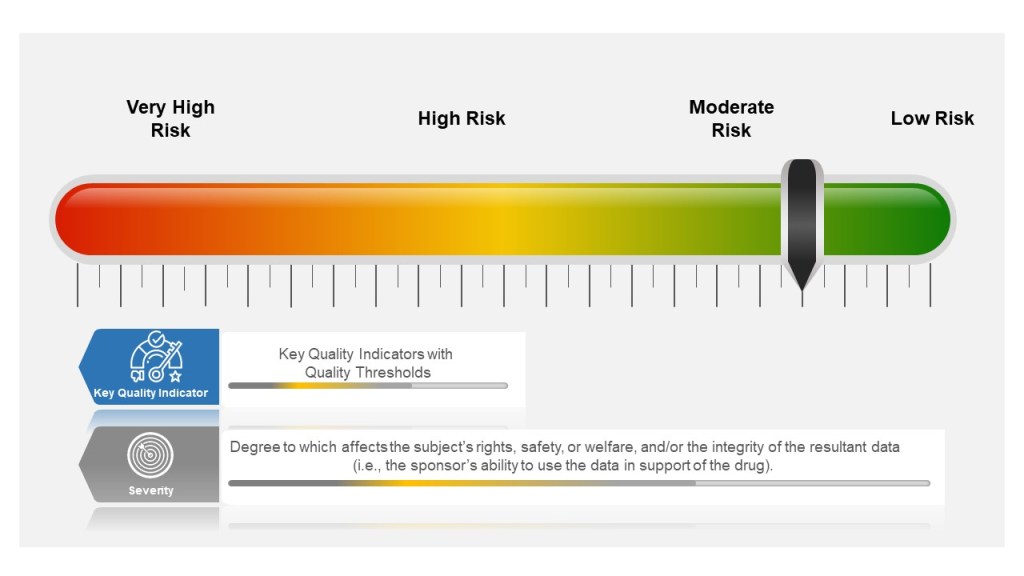

The interplay between emergence and success/failure space reveals a fundamental tension in managing complex systems: our ability to anticipate outcomes is constrained by both the unpredictability of component interactions and the inherent asymmetry between defining success and preventing failure. Emergence is not merely a technical challenge, but a manifestation of how systems oscillate between latent potential and realized risk.

The Duality of Success and Failure Spaces

Systems exist in a continuum where:

- Success space encompasses infinite potential pathways to desired outcomes, characterized by continuous variables like efficiency and adaptability.

- Failure space contains discrete, identifiable modes of dysfunction, often easier to consensus-build around than nebulous success metrics.

Emergence complicates this duality. While traditional risk management focuses on cataloging failure modes, emergent behaviors—particularly strong emergence—defy this reductionist approach. Failures can arise not from component breakdowns, but from unexpected couplings between validated subsystems operating within design parameters. This creates a paradox: systems optimized for success space metrics (e.g., throughput, cost efficiency) may inadvertently amplify failure space risks through emergent interactions.

Emergence as a Boundary Phenomenon

Emergent behaviors manifest at the interface of success and failure spaces:

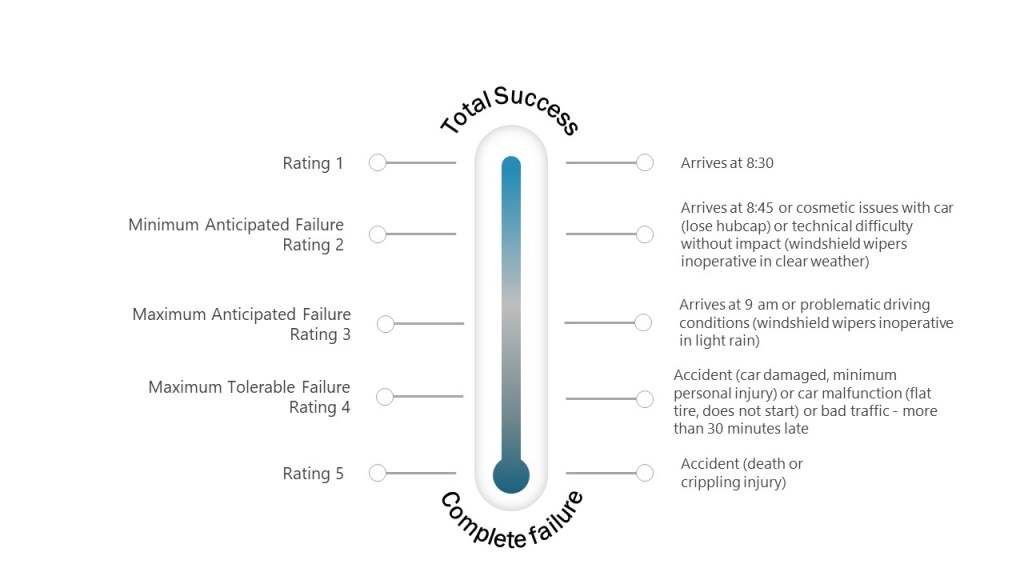

- Weak Emergence

Predictable through detailed modeling, these behaviors align with traditional failure space analysis. For example, a pharmaceutical plant might anticipate temperature excursion risks in cold chain logistics through FMEA, implementing redundant monitoring systems. - Strong Emergence

Unpredictable interactions that bypass conventional risk controls. Consider a validated ERP system that unexpectedly generates phantom batch records when integrated with new MES modules—a failure emerging from software handshake protocols never modeled during individual system validation.

To return to a previous analogy of house purchasing to illustrate this dichotomy: while we can easily identify foundation cracks (failure space), defining the “perfect home” (success space) remains subjective. Similarly, strong emergence represents foundation cracks in system architectures that only become visible after integration.

Reconciling Spaces Through Emergence-Aware Design

To manage this complexity, organizations must:

1. Map Emergence Hotspots

Emergence hotspots represent critical junctures where localized interactions generate disproportionate system-wide impacts—whether beneficial innovations or cascading failures. Effectively mapping these zones requires integrating spatial, temporal, and contextual analytics to navigate the interplay between component behaviors and collective outcomes..

2. Implement Ambidextrous Monitoring

Combine failure space triggers (e.g., sterility breaches) with success space indicators (e.g., adaptive process capability) – pairing traditional deviation tracking with positive anomaly detection systems that flag beneficial emergent patterns.

3. Cultivate Graceful Success

Graceful success represents a paradigm shift from failure prevention to intelligent adaptation—creating systems that maintain core functionality even when components falter. Rooted in resilience engineering principles, this approach recognizes that perfect system reliability is unattainable, and instead focuses on designing architectures that fail into high-probability success states while preserving safety and quality.

- Controlled State Transitions: Systems default to reduced-but-safe operational modes during disruptions.

- Decoupled Subsystem Design: Modular architectures prevent cascading failures. This implements the four layers of protection philosophy through physical and procedural isolation.

- Dynamic Risk Reconfiguration: Continuously reassess risk priorities using real-time data brings the concept of fail forward into structured learning modes.

This paradigm shift from failure prevention to failure navigation represents the next evolution of quality systems. By designing for graceful success, organizations transform disruptions into structured learning opportunities while maintaining continuous value delivery—a critical capability in an era of compressed innovation cycles and hyperconnected supply chains.

The Emergence Literacy Imperative

This evolution demands rethinking Deming’s “profound knowledge” for the complexity age. Just as failure space analysis provides clearer boundaries, understanding emergence gives us lenses to see how those boundaries shift through system interactions. The organizations thriving in this landscape aren’t those eliminating surprises, but those building architectures where emergence more often reveals novel solutions than catastrophic failures—transforming the success/failure continuum into a discovery engine rather than a risk minefield.

Strategies for Emergence-Aware Quality Leadership

1. Cultivate Systemic Literacy

Move beyond component-level competence. Trains quality employees in basic complexity science..

2. Design for Graceful Failure

When emergence inevitably occurs, systems should fail into predictable states. For example, you can redesign batch records with:

- Modular sections that remain valid if adjacent components fail

- Context-aware checklists that adapt requirements based on real-time bioreactor data

- Decoupled approvals allowing partial releases while investigating emergent anomalies

3. Harness Beneficial Emergence

The most advanced quality systems intentionally foster positive emergence.

The Emergence Imperative

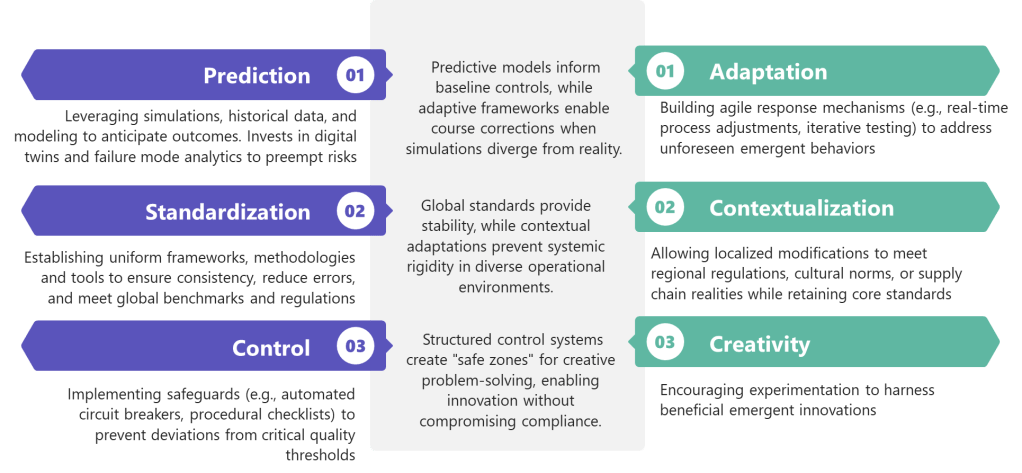

Future-ready quality professionals will balance three tensions:

- Prediction AND Adaptation : Investing in simulation while building response agility

- Standardization AND Contextualization : Maintaining global standards while allowing local adaptation

- Control AND Creativity : Preventing harm while nurturing beneficial emergence

The organizations thriving in this new landscape aren’t those with perfect compliance records, but those that rapidly detect and adapt to emergent patterns. They understand that quality systems aren’t static fortresses, but living networks—constantly evolving, occasionally surprising, and always revealing new paths to excellence.

In this light, Aristotle’s ancient insight becomes a modern quality manifesto: Our systems will always be more than the sum of their parts. The challenge—and opportunity—lies in cultivating the wisdom to guide that “more” toward better outcomes.