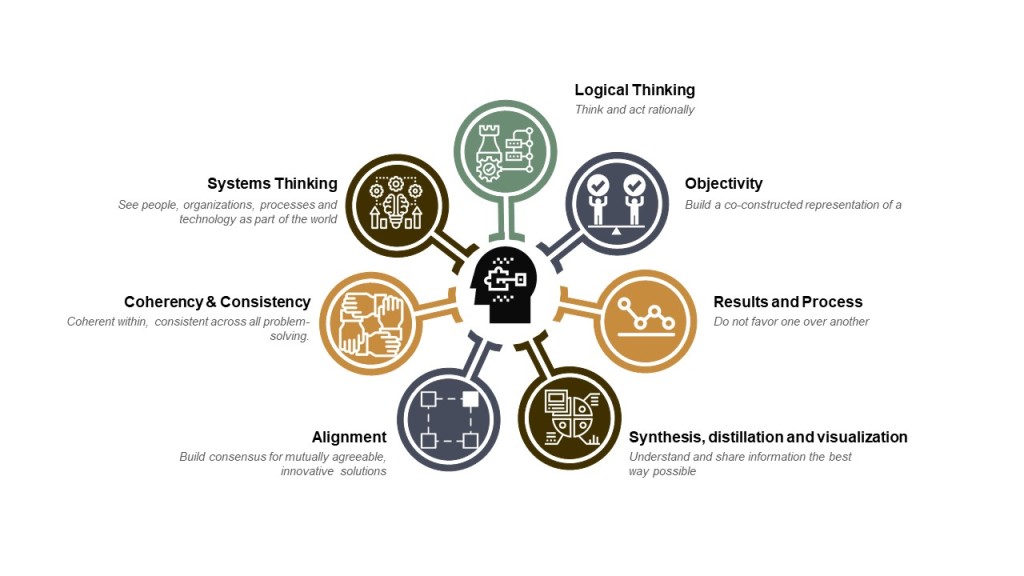

Being good at problem-solving is critical to success in an organization. I’ve written quite a bit on problem-solving, but here I want to tackle the amount of effort we should apply.

Not all problems should be treated the same. There are also levels of problems. And these two aspects can contribute to some poor problem-solving practices.

It helps to look at problems systematically across our organization. The iceberg analogy is a pretty popular way to break this done focusing on Events, Patterns, Underlying Structure, and Mental Model.

Events

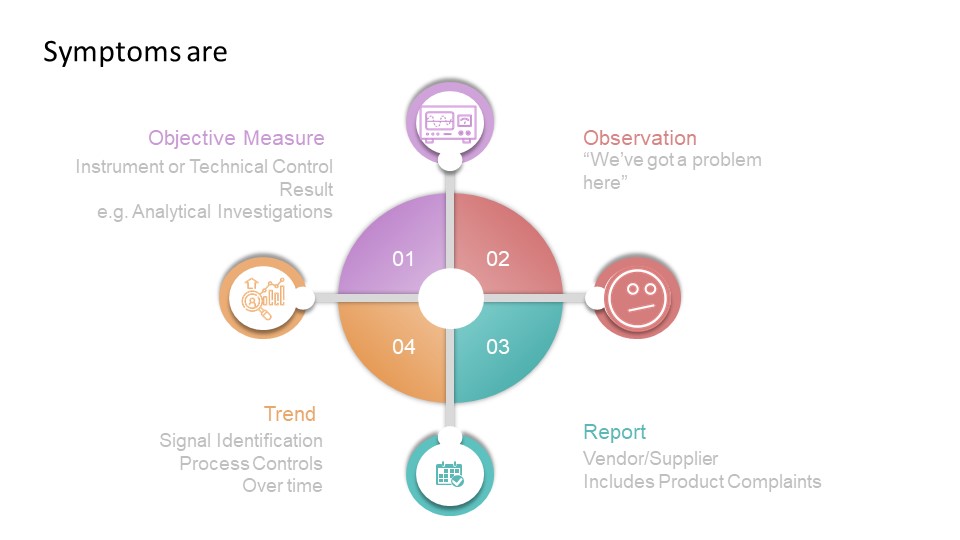

Events start with the observation or discovery of a situation that is different in some way. What is being observed is a symptom and we want to quickly identify the problem and then determine the effort needed to address it.

This is where Art Smalley’s Four Types of Problems comes in handy to help us take a risk-based approach to determining our level of effort.

Type 1 problems, Troubleshooting, allows us to set problems with a clear understanding of the issue and a clear pathway. Have a flat tire? Fix it. Have a document error, fix it using good documentation practices.

It is valuable to work the way through common troubleshooting and ensure the appropriate linkages between the different processes, to ensure a system-wide approach to problem solving.

Corrective maintenance is a great example of troubleshooting as it involved restoring the original state of an asset. It includes documentation, a return to service and analysis of data. From that analysis of data problems are identified which require going deeper into problem-solving. It should have appropriate tie-ins to evaluate when the impact of an asset breaking leads to other problems (for example, impact to product) which can also require additional problem-solving.

It can be helpful for the organization to build decision trees that can help folks decide if a given problem stays as troubleshooting or if it it also requires going to type 2, “gap from standard.”

Type 2 problems, gap from standard, means that the actual result does not meet the expected and there is a potential of not meeting the core requirements (objectives) of the process, product, or service. This is the place we start deeper problem-solving, including root cause analysis.

Please note that often troubleshooting is done in a type 2 problem. We often call that a correction. If the bioreactor cannot maintain temperature during a run, that is a type 2 problem but I am certainly going to immediately apply troubleshooting as well. This is called a correction.

Take documentation errors. There is a practice in place, part of good documentation practices, for addressing troubleshooting around documents (how to correct, how to record a comment, etc). By working through the various ways documentation can go wrong, applying which ones are solved through troubleshooting and don’t involve type 2 problems, we can create a lot of noise in our system.

Trends/Patterns

Core to the quality system is trending, looking for possible signals that require additional effort. Trending can help determine where problems lay and can also drive up the level of effort necessary.

Underlying Structure

Root Cause Analysis is about finding the underlying structure of the problem that defines the work applied to a type 2 problem.

Not all problems require the same amount of effort, and type 2 problems really have a scale based on consequences, that can help drive the level of effort. This should be based on the impact to the organization’s ability to meet the quality objectives, the requirements behind the product or service.

For example, in the pharma world there are three major criteria:

- safety, rights, or well-being of patients (including subjects and participants human and non-human)

- data integrity (includes confidence in the results, outcome, or decision dependent on the data)

- ability to meet regulatory requirements (which stem from but can be a lot broader than the first two)

These three criteria can be sliced and diced a lot of ways, but serve our example well.

To these three criteria we add a scale of possible harm to derive our criticality, an example can look like this:

| Classification | Description |

| Critical | The event has resulted in, or is clearly likely to result in, any one of the following outcomes: significant harm to the safety, rights, or well-being of subjects or participants (human or non-human), or patients; compromised data integrity to the extent that confidence in the results, outcome, or decision dependent on the data is significantly impacted; or regulatory action against the company. |

| Major | The event(s), were they to persist over time or become more serious, could potentially, though not imminently, result in any one of the following outcomes: harm to the safety, rights, or well-being of subjects or participants (human or non-human), or patients; compromised data integrity to the extent that confidence in the results, outcome, or decision dependent on the data is significantly impacted. |

| Minor | An isolated or recurring triggering event that does not otherwise meet the definitions of Critical or Major quality impacts. |

This level of classification will drive the level of effort on the investigation, as well as drive if the CAPA addresses underlying structures alone or drives to addressing the mental models and thus driving culture change.

Mental Model

Here is where we address building a quality culture. In CAPA lingo this is usually more a preventive action than a corrective action. In the simplest of terms, corrective actions is address the underlying structures of the problem in the process/asset where the event happened. Preventive actions deal with underlying structures in other (usually related) process/assets or get to the Mindsets that allowed the underlying structures to exist in the first place.

By applying this system perspective to our problem solving, by realizing that not everything needs a complete rebuild of the foundation, by looking holistically across our systems, we can ensure that we are driving a level of effort to truly build the house of quality.