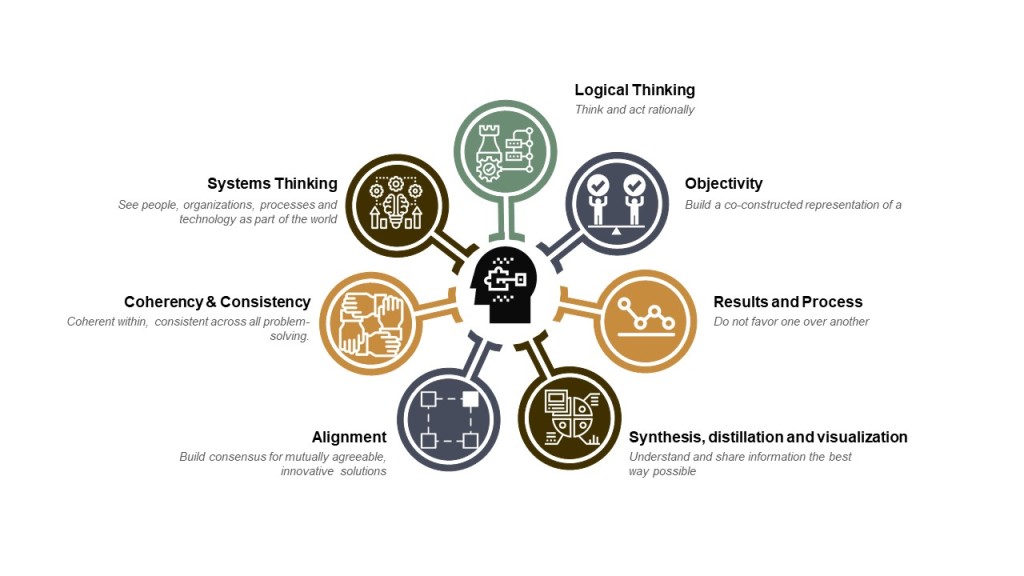

Logic

Perhaps more than anything else, we want our people to be able to think and then act rationally in decision making and problem-solving. The basic structure and technique embodied in problem solving is a combination of discipline when executing PDCA mixed with a heavy dose of the scientific method of investigation.

Logical thinking is tremendously powerful because it creates consistent, socially constructed approaches to problems, so that members within the organization spend less time spinning their wheels or trying to figure out how another person is approaching a given situation. This is an important dynamic necessary for quality culture.

The right processes and tools reinforce this as the underlying thinking pattern, helping to promote and reinforce logical thought processes that are thorough and address all important details, consider numerous potential avenues, take into account the effects of implementation, anticipate possible stumbling blocks, and incorporate contingencies. The processes apply to issues of goal setting, policymaking, and daily decision making just as much as they do to problem-solving.

Objectivity

Because human observation is inherently subjective, every person sees the world a little bit differently. The mental representations of the reality people experience can be quite different, and each tends to believe their representation is the “right” one. Individuals within an organization usually have enough common understanding that they can communicate and work together to get things done. But quite often, when they get into the details of the situation, the common understanding starts to break down, and the differences in how we see reality become apparent.

Problem-solving involves reconciling those multiple viewpoints – a view of the situation that includes multiple perspectives tends to be more objective than any single viewpoint. We start with one picture of the situation and make it explicit so that we can better share it with others and test it. Collecting quantitative (that is, objective) facts and discussing this picture with others is a key way in verifying that the picture is accurate. If it is not, appropriate adjustments are made until it is an accurate representation of a co-constructed reality. In other words, it is a co-constructed representation of a co-constructed reality.

Objectivity is a central component to the problem solving mindset. Effective problem-solvers continually test their understanding of a situation for assumptions, biases, and misconceptions. The process begins by framing the problem with relevant facts and details, as objectively as possible. Furthermore, suggested remedies or recommended courses of action should promote the organizational good, not (even if subconsciously) personal agendas.

Results and Process

Results are not favored over the process used to achieve them, nor is process elevated above results. Both are necessary and critical to an effective organization.

Synthesis, Distillation and and Visualization

We want to drive synthesis of the learning acquired in the course of understanding a problem or opportunity and discussing it with others. Through this multiple pieces of information from different sources are integrated into a coherent picture of the situation and recommended future action.

Visual thinking plays a vital role in conveying information and the act of creating the visualization aids the synthesis and distillation process.

Alignment

Effective implementation of a change often hinges on obtaining prior consensus among the parties involved. With consensus, everyone pulls together to overcome obstacles and make the change happen. Problem-solving teams communicates horizontally with other groups in the organization possibly affected by the proposed change and incorporates their concerns into the solution. The team also communicates vertically with individuals who are on the front lines to see how they may be affected, and with managers up the hierarchy to determine whether any broader issues have not been addressed. Finally, it is important that the history of the situation be taken into account, including past remedies, and that recommendations for action consider possible exigencies that may occur in the future. Taking all these into consideration will result in mutually agreeable, innovative solutions.

Coherency and Consistency

Problem-solving efforts are sometimes ineffective simply because the problem-solvers do not maintain coherency. They tackle problems that are not important to the organization’s goals, propose solutions that do not address the root causes, or even outline implementation plans that leave out key pieces of the proposed solution. So coherency within the problem-solving approach is paramount to effective problem resolution.

Consistent approaches to problem-solving speed up communication and aid in establishing shared understanding. Organizational members understand the implicit logic of the approach, so they can anticipate and offer information that will be helpful to the problem-solvers as they move through the process.

Systems Thinking

Good system thinking means good problem-solving.