In my recent exploration of the Jobs-to-Be-Done (JTBD) tool for process improvement, I examined how this customer-centric approach could revolutionize our understanding of deviation management. I want to extend that analysis to another fundamental challenge in pharmaceutical quality: risk management.

As we grapple with increasing regulatory complexity, accelerating technological change, and the persistent threat of risk blindness, most organizations remain trapped in what I call “compliance theater”—performing risk management activities that satisfy auditors but fail to build genuine organizational resilience. JTBD is a useful tool as we move beyond this theater toward risk management that actually creates value.

The Risk Management Jobs Users Actually Hire

When quality professionals, executives, and regulatory teams engage with risk management processes, what job are they really trying to accomplish? The answer reveals a profound disconnect between organizational intent and actual capability.

The Core Functional Job

“When facing uncertainty that could impact product quality, patient safety, or business continuity, I want to systematically understand and address potential threats, so I can make confident decisions and prevent surprise failures.”

This job statement immediately exposes the inadequacy of most risk management systems. They focus on documentation rather than understanding, assessment rather than decision enablement, and compliance rather than prevention.

The Consumption Jobs: The Hidden Workload

Risk management involves numerous consumption jobs that organizations often ignore:

- Evaluation and Selection: “I need to choose risk assessment methodologies that match our operational complexity and regulatory environment.”

- Implementation and Training: “I need to build organizational risk capability without creating bureaucratic overhead.”

- Maintenance and Evolution: “I need to keep our risk approach current as our business and threat landscape evolves.”

- Integration and Communication: “I need to ensure risk insights actually influence business decisions rather than gathering dust in risk registers.”

These consumption jobs represent the difference between risk management systems that organizations grudgingly tolerate and those they genuinely want to “hire.”

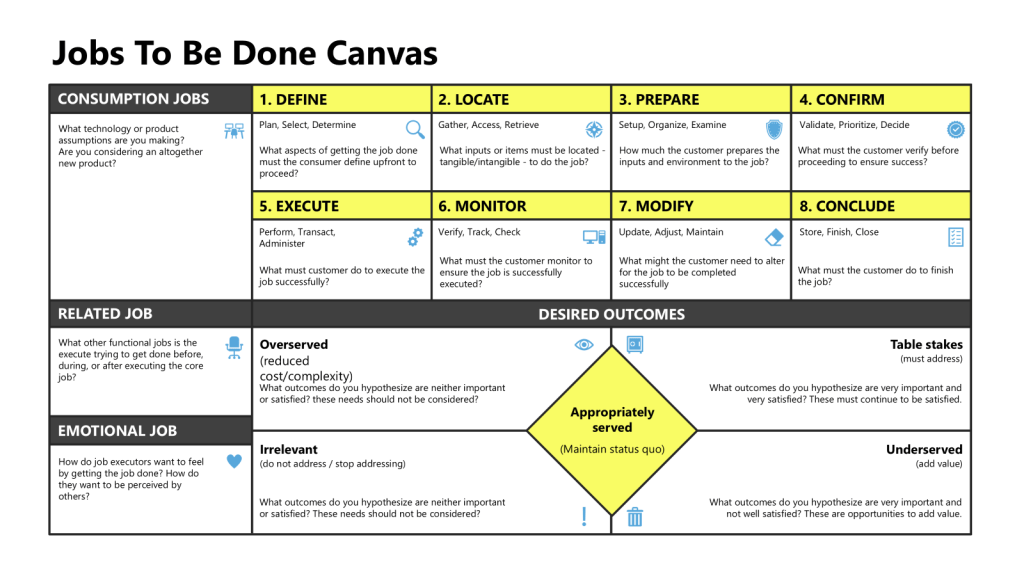

The Eight-Step Risk Management Job Map

Applying JTBD’s universal job map to risk management reveals where current approaches systematically fail:

1. Define: Establishing Risk Context

What users need: Clear understanding of what they’re assessing, why it matters, and what decisions the risk analysis will inform.

Current reality: Risk assessments often begin with template completion rather than context establishment, leading to generic analyses that don’t support actual decision-making.

2. Locate: Gathering Risk Intelligence

What users need: Access to historical data, subject matter expertise, external intelligence, and tacit knowledge about how things actually work.

Current reality: Risk teams typically work from documentation rather than engaging with operational reality, missing the pattern recognition and apprenticeship dividend that experienced practitioners possess.

3. Prepare: Creating Assessment Conditions

What users need: Diverse teams, psychological safety for honest risk discussions, and structured approaches that challenge rather than confirm existing assumptions.

Current reality: Risk assessments often involve homogeneous teams working through predetermined templates, perpetuating the GI Joe fallacy—believing that knowledge of risk frameworks prevents risky thinking.

4. Confirm: Validating Assessment Readiness

What users need: Confidence that they have sufficient information, appropriate expertise, and clear success criteria before proceeding.

Current reality: Risk assessments proceed regardless of information quality or team readiness, driven by schedule rather than preparation.

5. Execute: Conducting Risk Analysis

What users need: Systematic identification of risks, analysis of interconnections, scenario testing, and development of robust mitigation strategies.

Current reality: Risk analysis often becomes risk scoring—reducing complex phenomena to numerical ratings that provide false precision rather than genuine insight.

6. Monitor: Tracking Risk Reality

What users need: Early warning systems that detect emerging risks and validate the effectiveness of mitigation strategies.

Current reality: Risk monitoring typically involves periodic register updates rather than active intelligence gathering, missing the dynamic nature of risk evolution.

7. Modify: Adapting to New Information

What users need: Responsive adjustment of risk strategies based on monitoring feedback and changing conditions.

Current reality: Risk assessments often become static documents, updated only during scheduled reviews rather than when new information emerges.

8. Conclude: Capturing Risk Learning

What users need: Systematic capture of risk insights, pattern recognition, and knowledge transfer that builds organizational risk intelligence.

Current reality: Risk analysis conclusions focus on compliance closure rather than learning capture, missing opportunities to build the organizational memory that prevents risk blindness.

The Emotional and Social Dimensions

Risk management involves profound emotional and social jobs that traditional approaches ignore:

- Confidence: Risk practitioners want to feel genuinely confident that significant threats have been identified and addressed, not just that procedures have been followed.

- Intellectual Satisfaction: Quality professionals are attracted to rigorous analysis and robust reasoning—risk management should engage their analytical capabilities, not reduce them to form completion.

- Professional Credibility: Risk managers want to be perceived as strategic enablers rather than bureaucratic obstacles—as trusted advisors who help organizations navigate uncertainty rather than create administrative burden.

- Organizational Trust: Executive teams want assurance that their risk management capabilities are genuinely protective, not merely compliant.

What’s Underserved: The Innovation Opportunities

JTBD analysis reveals four critical areas where current risk management approaches systematically underserve user needs:

Risk Intelligence

Current systems document known risks but fail to develop early warning capabilities, pattern recognition across multiple contexts, or predictive insights about emerging threats. Organizations need risk management that builds institutional awareness, not just institutional documentation.

Decision Enablement

Risk assessments should create confidence for strategic decisions, enable rapid assessment of time-sensitive opportunities, and provide scenario planning that prepares organizations for multiple futures. Instead, most risk management creates decision paralysis through endless analysis.

Organizational Capability

Effective risk management should build risk literacy across all levels, create cultural resilience that enables honest risk conversations, and develop adaptive capacity to respond when risks materialize. Current approaches often centralize risk thinking rather than distributing risk capability.

Stakeholder Trust

Risk management should enable transparent communication about threats and mitigation strategies, demonstrate competence in risk anticipation, and provide regulatory confidence in organizational capabilities. Too often, risk management creates opacity rather than transparency.

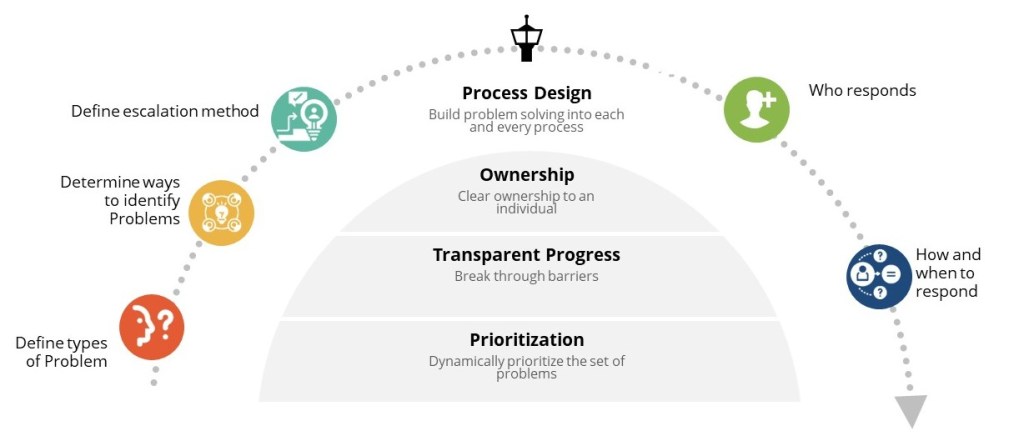

Moving Beyond Compliance Theater

The JTBD framework helps us address a key challenge in risk management: many organizations place excessive emphasis on “table stakes” such as regulatory compliance and documentation requirements, while neglecting vital aspects like intelligence, enablement, capability, and trust that contribute to genuine resilience.

This represents a classic case of process myopia—becoming so focused on risk management activities that we lose sight of the fundamental job those activities should accomplish. Organizations perfect their risk registers while remaining vulnerable to surprise failures, not because they lack risk management processes, but because those processes fail to serve the jobs users actually need accomplished.

Design Principles for User-Centered Risk Management

- Context Over Templates: Begin risk analysis with clear understanding of decisions to be informed rather than forms to be completed.

- Intelligence Over Documentation: Prioritize systems that build organizational awareness and pattern recognition rather than risk libraries.

- Engagement Over Compliance: Create risk processes that attract rather than burden users, recognizing that effective risk management requires active intellectual participation.

- Learning Over Closure: Structure risk activities to build institutional memory and capability rather than simply completing assessment cycles.

- Integration Over Isolation: Ensure risk insights flow naturally into operational decisions rather than remaining in separate risk management systems.

Hiring Risk Management for Real Jobs

The most dangerous risk facing pharmaceutical organizations may be risk management systems that create false confidence while building no real capability. JTBD analysis reveals why: these systems optimize for regulatory approval rather than user needs, creating elaborate processes that nobody genuinely wants to “hire.”

True risk management begins with understanding what jobs users actually need accomplished: building confidence for difficult decisions, developing organizational intelligence about threats, creating resilience against surprise failures, and enabling rather than impeding business progress. Organizations that design risk management around these jobs will develop competitive advantages in an increasingly uncertain world.

The choice is clear: continue performing compliance theater, or build risk management systems that organizations genuinely want to hire. In a world where zemblanity—the tendency to encounter negative, foreseeable outcomes—threatens every quality system, only the latter approach offers genuine protection.

Risk management should not be something organizations endure. It should be something they actively seek because it makes them demonstrably better at navigating uncertainty and protecting what matters most.