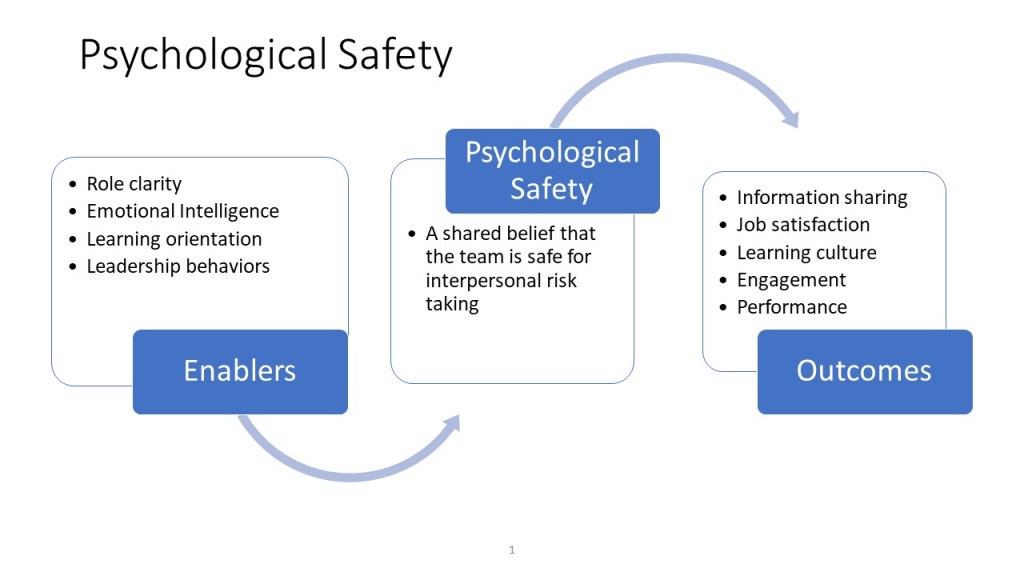

Our organizations are based on the interactions of individuals, teams and other organizations into a complex adaptive environment. We need to manage productive relationships as part of a complex system and interactions among parts can produce valuable, new, and unpredictable capabilities that are not inherent in any of the parts acting alone. This is why knowledge management, having a learning culture, is such a fundamental part of the work we do.

There are seven major categories we engage in when we manage, maintain, and create knowledge.

| Activity | Converts | Involving | Meaning |

| Socialization | Tacit-to-Tacit | different agents | Sharing of tacit knowledge between individuals |

| Introspection | Tacit-to-Tacit | same agent | The conscious or unconscious examination of one’s own tacit knowledge, as taken at an individual level |

| Externalization | Tacit-to-Explicit | agent to knowledge management | The expression of tacit knowledge and its translation into comprehensible forms interpretable by external agents |

| Combination | Explicit-to-Explicit | All users | The conversion of explicit knowledge into other variants of explicit knowledge |

| Internalization | Explicit-to-Tacit | Training and deliberate practice | The conversion of explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge |

| Conceptualization | Action-to-Tacit | Continuous Improvement | The creation of tacit knowledge from aspects related to real work actions. |

| Reification | Tacit-to-Action | Process/Procedure | The activity of bringing tacit knowledge into action (e.g. translating a mental model of a process activity into the actual operating tasks) |

As can be seen in the table above these seven activities involve moving between tacit and explicit knowledge. The apply to both declarative and procedural knowledge.

Socialization

Socialization is the level of interaction between, and communication of, various actors within an organization, which leads to the building of personal familiarity, improved communication, and problem solving. Often called learning the roles, this is the the process by which an individual acquires the social knowledge and skills necessary to assume an organizational role. Socialization encourages two-way information exchange, builds and establishes relationship trust, and enable transparency of information.

Socialization creates an operating style, enabling people to communicate with each other, have a language that they all understand and behavioral styles that are compatible. It reinforces basic assumptions and shares espoused values by helping create common norms and compatible cultures.

Socialization enables many influencing tactics which makes it critical for change management activities.

Introspection

The exploration of our experiences. Introspection can arise naturally but it can also arise deliberatively, for example journaling.

Introspection can also include retrospection, especially as a group activity. This is the strength of lessons learned.

Externalization

The work of making the tacit explicit. Knowledge management as continuous improvement.

Combination

The combination of knowledge drives innovation and a learning culture. This includes the ability to identify different sources of knowledge, understand different learning processes, and combine internal and external knowledge effectively.

Knowledge combination capability generates through exchange of knowledge between individuals and work teams is a process that allows the transfer of knowledge to the organization and that can be applied to develop and improve products and processes.

Internalization

As we move towards qualification we internalize knowledge.

Conceptualization

The insights gained from doing and observing work. Deliberative learning.

Reification

The process of translating work-as-imagined into work-as-done through work-as-prescribed on a continuous loop of improvement. The realm of transformative learning.